Hither Came Conan: Fred Adams on “The Black Stranger”

Welcome back to the latest installment of Hither Came Conan, where a leading Robert E. Howard expert examines one of the original Conan stories each week, highlighting what’s best. Fred Adams talks about “The Black Stranger.” Which was a story that Howard failed to get published, was rewritten without Conan, and still rejected. Fred takes a brand new look at the story. Read on!

Conan as Picaro in “The Black Stranger”

There are days when I ask myself whether Robert E. Howard didn’t sneak away for four years and earn a degree in English Letters when I encounter his facility with literary tropes and conventions. Many would suggest that the influence of the great western writers rubbed off on him from his omnivorous reading, others simply that he labored past mediocrity to instinctively hone his considerable skills at writing, recognizing what worked and what did not.

Whichever the case, he made good use of a variety of literary conventions and techniques, as David C. Smith elaborates in his Robert E. Howard: A Literary Biography. One that I have noticed specifically is his use of the picaresque mode of the novel. A good example is his experimentation with the form in the Conan story “The Black Stranger.”

Harmon and Holman’s A Handbook to Literature, Seventh Edition defines “Picaresque Novel” at great length:

“A chronicle, usually autobiographical, presenting the life story of a rascal of low degree engaged in menial tasks and making his living more through his wits than his industry. The picaresque novel tends to be episodic and structureless. The picaro, or central figure, through various pranks and predicaments and by his associations with people of varying degree, affords the author an opportunity for satire of the social classes. Romantic in the sense of being an adventure story, the picaresque novel nevertheless is strongly marked by realism in petty detail and by uninhibited expression.” (389)

To call Conan a “rascal of low degree” is mild at best, but to say that he lives “more through his wits than his industry” seems close to his nature. Conan is a barbarian with no social standing whatsoever who lives by his wits as a thief, a reaver, and a warrior. True to the form, he begins the story in a loincloth running for his life from a tribe of savages. By the time the tale ends, Conan has attained the kingly position of leader of the Red Brotherhood, and possessed of enough wealth that he gives a bag of rubies worth a fortune to Belesa saying, “What are a handful of gems to me, when all the loot of the southern seas will be mine for the grasping?”

Before the literary among you cry foul, May I remind you that I suggest that Howard experiments with the form, pragmatically using what works and eschewing what does not as he portrays Conan in the mode of the picaro.

Harmon and Holman offer seven primary characteristics of the picaresque novel, and “The Black Stranger” embodies each to the degree to which Howard finds them useful.

1. It chronicles a part of the life of a rogue. It is likely to be in the first person.

“Rogue” is a suitable word to describe Conan, who makes his way as a thief, a reaver, and a warrior. Because of the shifting point of view, Howard presents “The Black Stranger” as he does in all of his Conan stories, in the third rather than the first person.

2. The chief character is drawn from a low social level, is of loose character, and, if employed at all, does menial work.

Conan has little use for society’s mores. He tells Belesa, “Aye, I’ve seen men fall and die of hunger against the walls of shops and storehouses crammed with food. Sometimes I was hungry, too, but then I took what I wanted at sword’s-point.”

Conan has little use for society’s mores. He tells Belesa, “Aye, I’ve seen men fall and die of hunger against the walls of shops and storehouses crammed with food. Sometimes I was hungry, too, but then I took what I wanted at sword’s-point.”

3. The novel presents a series of episodes only slightly connected.

Here, Howard, the master storyteller departs from the picaresque mode. “The Black Stranger” is built upon episodic scenes, but each contributes to the narrative whole, leading to climax and resolution of the various conflicts woven into the story.

4. Progress and development of character do not take place.

I believe it is fair to say that the story’s end finds Conan unchanged from his nature at the start. He is still a barbarian, and although as head of the Red Brotherhood he can operate on a grander scale, he is still a reaver and a thief. His aspiration at the story’s end?

“. . . as soon as I’ve set you and the girl ashore on the Zingaran coast, I’ll show the dogs some looting!”

This maintenance of his character is also manifest in his unswerving adherence to his code of honor, contrasting Valenso, who is ready to trade his niece to the pirate captain Zarono in exchange for escape from his nemesis and a share of Tranicos’ treasure. From Belesa’s point of view, Howard tells us,

“He was not like the freebooters, civilized men who had repudiated all standards of honor, and lived without any. Conan, on the other hand, lived according to the code of his people, which was barbaric and bloody, but at least upheld its own peculiar standards of honor.”

5. The method is realistic . . . . with a plainness of language and vividness of detail . . . .

Howard’s prose qualifies on this score; even when he presents the most fantastic scenes, they are executed in sharp prose, painting a vivid picture in the reader’s mind.

6. Thrown with people from every class and often from different parts of the world, the picaro serves them intimately in some lowly capacity and learns all their foibles and frailties. The picaresque novel may, in this way, be made to satirize social castes, national types, or ethnic peculiarities.

Howard, realizing that Conan would serve no one in a menial fashion, allows us to see the flaws in the various castes and classes through their actions, largely apart from Conan’s direct observation. Royal Pretension through the pompous Valenso, who builds a rude replica of his former palace on a jungle island to remind himself of past glory; Knavery through the duplicitous Zarono, and Debauchery through the drunken Picts are all held up for judgment and ridicule by the reader and contrasted by Conan’s singleness of purpose and unswerving adherence to his barbarian code.

7. The hero usually stops just short of being an actual criminal. The line between crime and petty rascality is hazy, but somehow, the picaro always manages to draw it.

Here, Howard departs from the convention as Conan commits acts that qualify as criminal in civilized society, but are acceptable to the reader in the context of his situation. As I’ve often said, pulp fiction demands internal logic, but not external logic. The things he does are less evil than those done by so-called “civilized” men, and are done for the sake of survival. And survive he does, with Howard’s promise of more adventures to come.

Howard may not have known the term picaresque, but his omnivorous reading apparently acquainted him with the concept. It is testimony to his literary craft that he was able to adapt a centuries-old form to the tastes and aesthetics of a modern popular fiction audience. His instincts were good, and his skill as a writer allowed him to step outside the bounds of literary convention to create entertaining fiction.

Howard knew, in the words of Kenny Rogers, “what to throw away . . . and what to keep” in his literary experimentation. One can only imagine what wonders he may have created if only he’d lived long enough to die in his sleep.

From the Dusty Scrolls (Editor comments)

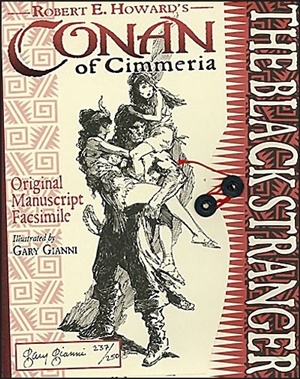

Written after “Beyond the Black River,” this is another frontier story (as is “Wolves Beyond the Border,” which Howard worked on around this time as well). But Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright didn’t want it. It did not appear in it’s original, complete form, until 1987’s Echoes of Valor. Del Rey’s The Conquering Sword of Conan includes two of Howard’s synopsis’ for the story. At 30,000-ish words, this qualifies as a Conan novella.

When Howard couldn’t sell “The Black Stranger” as a Conan story, he rewrote it as “Swords of the Red Brotherhood,” starring the pirate Black Vulmea. Vulmea was an Irish pirate in the seventeenth century Caribbean. Shortly after Howard’s death it sold, but the magazine went out of business. It finally appeared, along with another Howard story featuring the pirate in 1976’s Black Vulmea’s Vengeance.

When Howard couldn’t sell “The Black Stranger” as a Conan story, he rewrote it as “Swords of the Red Brotherhood,” starring the pirate Black Vulmea. Vulmea was an Irish pirate in the seventeenth century Caribbean. Shortly after Howard’s death it sold, but the magazine went out of business. It finally appeared, along with another Howard story featuring the pirate in 1976’s Black Vulmea’s Vengeance.

More of the saga: L. Sprague de Camp rewrote the still-unpublished “The Black Stranger” as “The Treasure of Tranicos” for the 1953 King Conan from Gnome Press. He retconned the ending to set up Conan’s rise to King of Aquilonia.

Of the original version, de Camp said that “it displays the faults of careless plotting” and that “two of the menaces…are vague and unconvincing.” Commenting on his own version, he said, “Howard’s heroes were mostly cut from the same cloth. It was mostly a matter of changing names, eliminating gunpowder, and dragging in a supernatural element.”

Steve Tompkins wrote an excellent essay on this story.

I very much like this rousing pirate adventure tale – both the Howard and de Camp versions. But the scene in which Valenso whips the child Tina, repeatedly, is as offensive as anything in the Conan Canon. Even if Howard was writing one of his ‘This will get me a Margaret Brundage cover’ scenes (which, frankly, is hard to imagine: a child is being brutalized), it’s an affront to the reader.

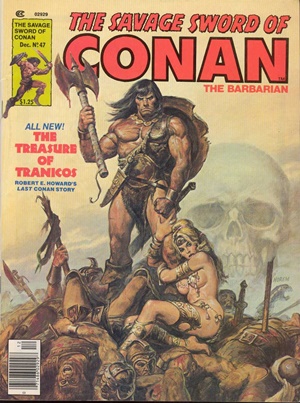

Marvel’s Savage Sword of Conan covered this story in issue 47 and 48.

Prior Posts in the Series:

Here Comes Conan!

The Best Conan Story Written by REH Was…?

Bobby Derie on “The Phoenix in the Sword”

Fletcher Vredenburgh on “The Frost Giant’s Daughter”

Ruminations on “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Jason M Waltz on “The Tower of the Elephant”

John C. Hocking on “The Scarlet Citadel”

Morgan Holmes on “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

David C. Smith on “The Pool of the Black One”

Dave Hardy on “The Vale of Lost Women”

Bob Byrne on Dark Horse’s “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

Jason Durall on “Xuthal of the Dusk”

Scott Oden on “The Devil in Iron”

James McGlothlin on “The Servants of Bit-Yakin”

Keith West on “Beyond the Black River”

Next Week it’s fellow Black Gater Steven Silver with “The Man-Eaters of Zamboula/Shadows in Zamboula.”

Now retired from his job as an English Professor for Penn State University, Fred is able to devote his full attention to writing fiction. For the past few years, he has focused on “New Pulp” fiction, creating series novels that include supernatural crime, supernatural western (i.e. Cowboys and Cthulhu), contemporary detective, and post WWI supernatural detective fiction. Four of his novels, Hitwolf, C. O. Jones: Mobsters and Monsters, Six Gun terrors vol. 1 and Six Gun Terrors vol. 2 were published by Airship 27 Productions in 2014 and 2015 and three more are due out from Airship 27 over the next year.

In addition, he writes genre stories for Airship 27’s many new-pulp fiction anthologies. His story “Masks” recently appeared in Laurel Highlands Publishing’s horror anthology Moonshadows and his story “Astrotrash” will soon appear in LHP’s science fiction anthology Across the Kármán Line. Fred’s novella The Chaos Spawn has recently been re-released after being long out of print in a 40th anniversary special edition on Amazon Kindle. When he’s not writing, Fred plies his trade as a singer-songwriter performing in local venues including Castle Blood and the Western Pennsylvania Renaissance Festival

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he is in a new anthology of new Solar Pons stories, out now.

What a fascinating lens through which to view the story! Points to Adams for his unique approach. I’m not convinced, however, that the Picaresque novel did in fact have any influence on Howard. Conan just doesn’t fit the seven Harmon and Holman characteristics (which, as stated, actually constitute fifteen, by my count). Adams explores how this Conan story matches them, and it’s just not a good fit. Let’s look at them in more detail:

1. Hero a rogue? Yes. Narrative first person? No. Fit: 50%

2. Hero of low social level? Yes. Loose character? Needs more detailed examination, but I would argue no. Does menial work? Not really in this story. Fit: 33 1/3%

3. Story episodic? Yes. Only slight connection between episodes? No. Fit: 50%

4. Character fails to progress? No; Conan goes from fugitive to pirate chief. Character fails to develop? Yes. Fit: 50%

5. Realistic method? Yes. Plain language? Dunno; Howard’s style varies in lushness. Adams doesn’t really rate it here, and I would have to reread the story myself to assess it. Vivid description? Yes. Fit: 33 1/3-66 2/3%, depending.

6. Thrown in with every class? Yes. Serves in lowly fashion? No; in some stories maybe, but not this one. Fit: 50%

7. Stops short of criminality? Adams has a just quibble here, in that Conan is a cut above the other characters; nonetheless, this one’s an obvious no. Fit: 0%

Out of a possible 700 percentage points (100 for each H&H characteristic), “Black Stranger” racks up 266 2/3 to 300 1/3, depending on where one comes down on the second factor in characteristic 5. In either case, that’s well short of half of what’s needed for a perfect match.

If that’s all it takes for a GOOD match, then one could as easily argue a man is a good approximation of a woman, and a woman a good approximation of a man, when the actual commonality is that they’re both human. The actual commonality between Howard’s “Black Stranger” and the Picaresque novel is that both are examples of fictional narratives.

I note that Adams does not actually contend this is the best Conan tale. Of course, given its record of rejection in two forms, and the fact that the form in which it WAS first published was a drastically altered one, that would be a hard point to sell.

Parenthetically, I don’t think the issue of removing gunpowder is one we can lay to L. Sprague de Camp, the alterer in question, at least for this story. If memory serves, he was working from the Conan version, not the Vulmea one. Or, if he had both before him, he was plainly returning to the original one in this one instance.

Brian – my books are at home (a depressing thought as I go to work every morning…), but I think the de Camp attribution of (removing gunpowder) came from Mark Finn’s book.

I do recall for certain, that the ‘careless plotting/two menaces’ are from Dark Valley.

I really like this story. From the fleeing from the Picts, to the treasure cave, to the entire stockade/pirates storyline.

I find it hard to believe this one didn’t find a publisher in the day.

I don’t doubt the de Camp gunpowder quote, but I suspect it actually relates to the Afghanistan tales he converted to Conans. (I don’t doubt the other quote either. Jibes with my memory of what he wrote about his Conan editing, and Black Stranger/Treasure of Tranicos in particular.)

Yes, I like the story, too.

Yeah, I’m certain that the de Camp gunpowder quote is talking about the El Borak conversions.

My first introduction to the concept of a picaresque narrative was in relation to Jack Vance’s Eyes of the Overworld (the first Cugel book), which let’s see:

1. Rogue but third person

2. Low social level — difficult to say. He’s definitely of loose character and does menial work (when forced and with many protestations)

3. Only slightly connected episodes — Yep

4. Progress & development do not take place. Yes, Cugel at the end is Cugel at the beginning.

5. Realistic with plainness of language and vividness of detail. Well, one out of three (vividness) isn’t bad, right?

6. Thrown in with people of every class — yes, at one poiont or another.

7. Stops just short of being an actual criminal — um, no, Cugel does NOT stop short of actual criminality.

Thank you, Professor Adams!

While not seen as one of Howard’s best, this story has always been a favorite of mine (I know: is there a REH Conan story that ISN’T one of my favorites?). I think it has to do with the vividness of his imagery.

Here comes Conan, the only man alive who could fight his way across a thousand miles of Pictish wilderness and who then goes toe to toe with demon. Where? In a room full of dead pirate chieftains seated around a table in one last fatal conclave. Then there are the two gangs of living pirates, each led by a wolf in human form and Valenso, the terror-driven fugitive who still retains a few shreds of the nobleman he once was (My word is not straw!)

And what comes to everyone not under Conan’s protection? A violent death as the Picts come over the walls in a howling tide and paint the stockade timbers with the blood of pirate and henchmen alike.

This story has inspired at least a dozen scenarios in my rpg campaigns over the years. Thank you, Mr. Howard.

I agree with Brian, that this story fails of being picaresque—as opposed to picturesque. Also disappointed that no attempt was made to it being the best story—regardless of its publication history. That is the central point of this series of posts, I believe.

Terry – While the general idea of the series was to argue why each story was best, the real root was to pull out what was best in each story.

So, there was a lot of leeway for the contributors. I didn’t want to straitjacket folks. I wanted to give them some freedom to write the best essay they could.

Thus, some different approaches.

I’ve always enjoyed this story, especially the SSOC rendering. I enjoyed the interesting approach, but where’s the argument for ‘best of’? 😉

I also like your adage “pulp fiction demands internal logic, but not external logic,” Doc.

And that SSOC #47 is one of the best!

And I agree, Bob, I’ve never understood why it wasn’t accepted and published. It’s a rip-roaring tale as far as I’m concerned.