The Monster and the Ape

A true oddity in the history of robots is the complete absence of robot films in American cinema before the 1950s. By my count studios made exactly zero full-length feature films with a major robot character. Not even Universal, at its twin peaks of fabulously successful and highly profitable monster movies in the 1930s and 1940s, thought to include a robot hero, antihero, or villain.

Would-be robot historians have to cheat mightily to drag a robot into their texts. For unknown reasons they credit Universal’s low-budget Man-Made Monster as a robot film. The title monster is a circus freak who can absorb electricity. Feeding him with ever-greater amounts of volts turns him into a mind-controlled, rampaging but still-human monster. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is a favorite because of the Tin Man. The Tim Man – Nick Chopper as he would be named in a later Oz book – has a metal body but retains his human (or Ozian) personality. He’s a cyborg, not a robot. His greatest wish is for a heart, to make him even more human. (Baum created a true mechanical man, Tik-Tok, but just try finding him in a movie.) You might even see a mention of Basil Rathbone’s Fingers at the Window, whose newspaper ads scream “Mystery of the Robot Murders,” but whose monsters are hypnotized humans.

Therefore, even in an era we fondly remember for its pure cheeziness, robots are low-grade Gheeze Whiz. To find any, cinemaphiles need to descend to the bottom of the Hollywood pecking order, the serials.

Robots are we recognize them today burst onto the screen in Houdini’s 15-part serial The Master Mystery. (Yes, that Houdini.) It made money, but not enough to keep the studio from folding. Nothing followed for more than a decade until Mascot Pictures (whose name even sounds like the lowest of the low; it merged into Republic Pictures shortly after) released the hallucinogenic Phantom Empire in 1935. The lost continent of Mu happened to sink into the ocean right underneath Gene Autry’s ranch. They have an advanced civilization and use radium, which attracts evil surface people who draw the wrath of the Muranians. Fortunately, there is an elevator down to Mu that’s handily available, and Gene needs to defeat them and get back to Hollywood before his radio show begins. (I’m going to get tired of saying “Yes. Really.” before this ends. Take it as read whenever your jaw starts dropping.)

The robots of Mu are the cheesiest ever billed as monsters, mostly because they were taken out of the prop room where they had been kept since their scenes had been cut out of Fred Astaire’s first movie, the musical comedy Dancing Lady. Phantom Empire was followed and, for incomprehensible reasons, its plot if not its robots was blatantly imitated by Undersea Kingdom (1936), starring Ray “Crash” Corrigan. And those robots were blatantly imitated in 1940 by the Mysterious Doctor Satan. Some truly ugly robots debuted in 1939’s The Phantom Creeps (1939), bad enough to kill off any trend.

|

|

|

Universal saw the trend and jumped in with a Flash Gordon serial in 1936. Flash (Buster Crabbe) fought Mongo’s mechanized mechanical men. More robots returned in 1940’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe. Both sets of robots were among the dullest ever put on screen by supposed professionals. The latter robots are known as “Annihalatons” and are like really scary with their spears and all.

|

|

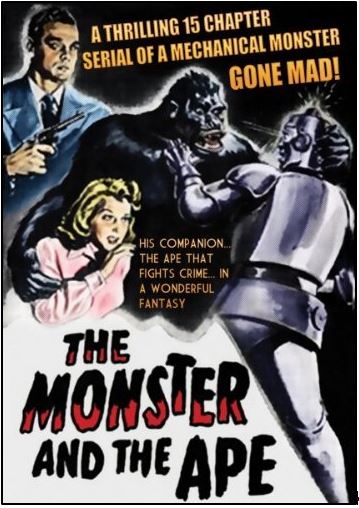

After the second Flash, robots disappear from the screen until the 1950s.Or so I thought. Somehow all the lists of robots films I consulted omitted 1945’s The Monster and the Ape.

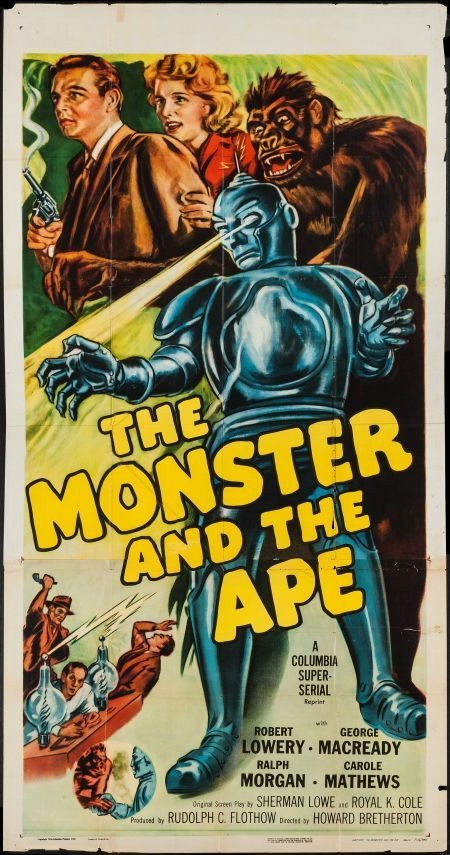

TMATA, as I like to call it, came from Columbia Pictures, then metaphorically next-door neighbor to Republic on Hollywood’s Poverty Row. Columbia is nevertheless much beloved by z-movie fanatics, largely for its habit of plucking favorite characters out of the pulps and comic strips. They made serials out of The Shadow, The Phantom, The Spider, Terry and the Pirates, Brick Bradford, and Mandrake, the Magician, audaciously gave a female the lead role in Brenda Starr, Reporter, and filmed the first live-action appearances of Batman and Superman.

Several of these were written by Royal K. Cole or Sherman Lowe, who teamed up for the TMATA script. Howard Bretherton, a western specialist who started directing in 1926, was making his hundredth or so picture. The western influence probably explains why he loved fight scenes so much he put them into every one of the 15 chapters. TMATA runs around four hours of screen time (once all the repeated catch-up-the-audience scenes inherent in serials are cut) and it was one of seven movies he directed that year. Given the fantastic speed required by all, TMATA is quite an accomplishment. It’s far less idiotic than the 1930s serials and if cut to a shorter length could easily pass for a normal b-picture. Even the plot stays within the lines drawn by a million other crime pictures. I say crime picture deliberately. TMATA isn’t science fiction, except by the catch-all definition that any picture with a robot is science fiction. The plot hinges entirely on the maguffin that the bad guys want and keep trying to steal; all the action centers on the good guys fighting the bad guys, getting knocked out and put into death traps by the bad guys, and finally foiling the bad guys. The trailer merely hints at the goodies awaiting.

Chapter 1 is pure exposition, setting up the plot and in many ways more interesting than the plot. A series of newspaper headlines start it off.

SCIENTISTS COMPLETE MECHANICAL MAN

This Robot Radically Differs from

Previous Automatons, Say Scientists

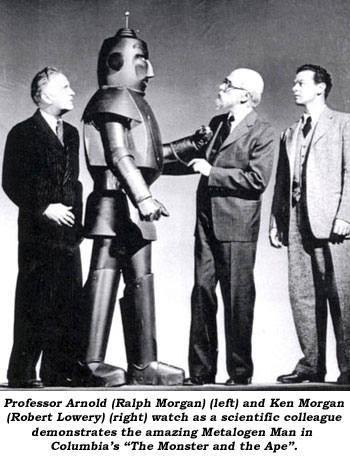

The narration tells us that five of the world’s foremost inventors are making final adjustments on the “weird mechanism of wires, tubes, and scientific instruments known as the Metalogen Man.” “This robot represents harnessed power undreamed of by mortal man,” seriously underestimating dreams. “The Metalogen Man will free the human race from the shackles of manual labor and industrial enslavement[!]” Robots in the 30s and 40s were always touted that way. That claim was a bit more understandable in April 1945, when the war effort had finally put unemployment to rest. Why inventors kept threatening to put even more people out of work during the Depression is a far harder socio-political question to answer. The just-around-the-corner utopia that would be their reward in the Future seemed to have blocked out all rational thoughts about the present, the Future becoming sort of a secular afterlife.

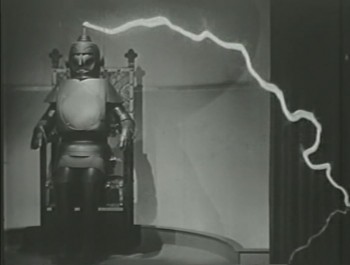

Despite the images on the poster and lobby card, the Metalogen Man does not shoot rays from his eyes. Quite the contrary. The scientists shoot wireless power to him.

|

|

That must have been quite a charge. In fact, they never show it again (obviously due to budgetary constraints for special effects, although the budget for explosions was bottomless) and the Metalogen Man just keeps running and running. He’s superstrong, though, lifting a huge block of stone with one hand.

After this triumphant reveal, disaster strikes. A mystery voice cuts into the radio in a car carrying two of the scientists, accusing them of stealing the glory that rightly belongs to another. They must be destroyed! You’re thinking that the robot will be sent against them. No. Their doom is closer to hand. Somehow they haven’t noticed that the entire back seat of their car is taken up by a man-sized gorilla who reaches out and strangles them. (Since they couldn’t smell the gorilla either you might be wondering if they had a large pot of beans for lunch.) The gorilla, whose name we later learn is Thor, then strangles a third scientist in his home.

(The gorilla – the Ape in the title – is played by Ray “Crash” Corrigan, who made romping in his gorilla costume his trademark during the 1940s. He’s said to have especially enjoyed this picture as it called for more action and more nuanced work than his usual rolls.)

That leaves two of the five, Professor Ernst, suave and oily, and Professor Franklin Arnold, a frail, kindly, older man who has a pretty daughter named Babs. Guess which one is the bad guy.

Neither Prof. Arnold nor Babs are up for fist fights, so Ken, the ruggedly handsome yet brilliant engineer, is brought in to help the Prof. at his Bainbridge Laboratories. The bad guys intercept him a train stop early. How did they know where to find him? While he worked on the robot, Ernst somehow managed to install television and radio gear inside him that none of the other four ever noticed. This television has an unusual property. It shows the outside of the robot, in fact the whole room it’s lying in, from exactly the angle the film camera would take. It even pans and cuts to close-ups! From today’s perspective, this is a far better invention than the robot. (Nor does its uncanny abilities end there. In a later episode, Arnold finds the device and removes it. That doesn’t stop Ernst from continuing to spy on them. Ah, sweet continuity. Fickle is thy name.)

Back at the plot, a pair of thugs pretending to be from Prof. Arnold take Ken for a ride. Literally. The city in the serial has the bizarre street layout endemic to serials and b-movies. No matter where anyone goes in town the route always passes through a long stretch of uninhabited wasteland, full of deadly cliffs and dead end roads. After a brisk fist fight, in which Ken almost overpowers both his opponents, he’s bashed in the head and tossed down a hill. Fortunately, he wears a suit provided by Clark Kent’s tailor, one which never tears, wrinkles, or smudges no matter what the wearer endures. When he climbs up the hill again, he’s a sharp-dressed man. Ernst steals the robot and hides it in his house, conveniently fixed up with sliding panels and an entrance to his underground laboratory through his fireplace. A hidden door leads to the outside, until a later chapter in which the door leads to another room, which leads to another room, which leads to a tunnel, which leads to… a hidden door in the gorilla cage at the Municipal Zoo. One of Ernst’s men works for the zoo and has trained Thor to do his bidding. Any time Ernst needs him, he goes into the cage, puts a chain on Thor, and leads him into battle. Nobody ever notices that the gorilla is missing.

There are fourteen chapters to go so forgive me if I compress the narrative. Ernst and his men steal the robot and, more importantly, his unique control panel. Ken gives chase. They finally regain the robot. Arnold plans to make thousands of robots. Only one hitch. The robot is revealed to have a gadget stuck to his thigh that carries energy waves to a step-up transformer inside his body. (Then what is the antenna for? Never mind.) The gadget is made of metalogen, a unique element found only in meteorites. So that’s what the Metalogen Man means. I wonder why they waited until Chapter 6 to reveal this? Ernst and his men steal all the metalogen from a museum but he’s tricked by fake meteorite powder so he kidnaps various good guys to threaten to torture them until the real metalogen’s hiding place is revealed. When they grab it, it gets blowed to bits while they’re trying to kill Ken. So there’s no more metalogen in the world. But hark! That very day, a front page story in a newspaper mentions a scientist who has a metalogen detector. Ernst gets there first – he and his men have been spying on them the whole time and they never think to holds their conversations in another room, steals the detector and impersonates the scientist.

Ernst proves to have several more pairs of thugs, who always attack Ken two at a time, just to make it a fair fight. They wear the magic suits as well, and more. Although they spend more of their time slugging each other in the face, nobody ever sports a bruise. I can see not putting in the special effects, but how expensive could a dab of makeup be? Ken also escapes from a pit of electricity, a car that is crushed after going off a cliff, a conveyor belt into a furnace, an explosion in a warehouse, constricting walls, and another explosion in a sewer tunnel. Not a scratch. Ernst’s men are just as hardy. When their truck explodes they walk away without even stoping for a band-aid. None of the many guns that everybody shoots off – including the plucky Babs – do any damage either. That’s made easier by their being such terrible shots that no bullet ever hits. (Except one that plows through the indestructible Ken. He and the plot ignore it.)

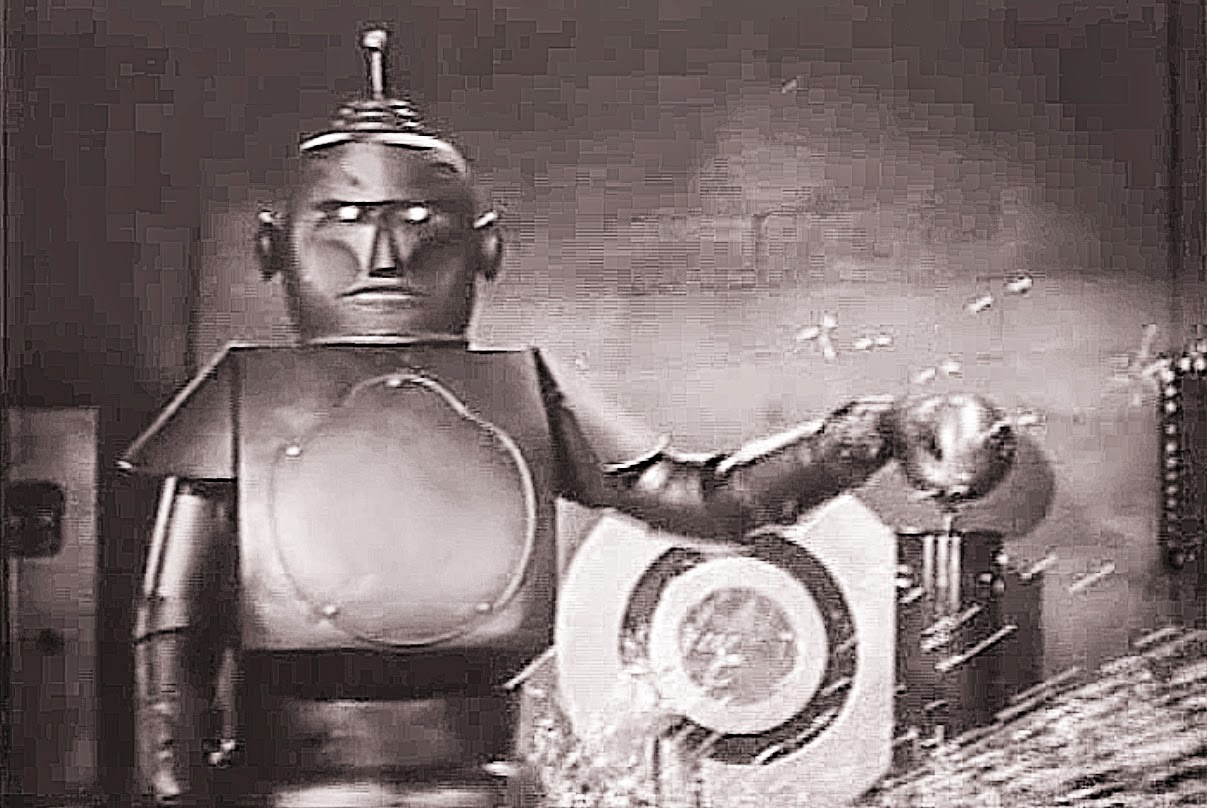

Eventually, Ernst, who has re-stolen the re-built robot, puts it to actual work. At last. The Ape has gotten far more screen time and far better scenes. The Metalogen Man spends most of its screen time sitting or shuffling slowly. Off screen it’s a whiz. In one chapter Ernst sends it by remote control after Ken, who has earlier left in a truck heading for one of Ernst’s lairs. The robot slowly shuffles across the lab, manages to turn the knob on the lab door after about thirty seconds of effect and shuffles out. Nevertheless, it gets to the lair at the same time as the truck.

What can be done with a robot who can lift heavy blocks of stone but is slower than a grandmother using a walker? Arnold’s use of the metalogen detector revealed that the city sewer tunnel (which looks suspiciously like the secret tunnel to Ernst’s house) had been stalled because workers ran into a huge and impenetrable metalogen meteorite. For some convenient reason, the tunnel is littered with … heavy blocks of stone. Ernst replaces the workers with his crew and uses the robot to stack blocks of stone conveniently left lying around to get at the meteorite so it can be blasted free.

Meanwhile, the Ape has decided not to return to his cage. This is it, what everyone has been waiting for, the great battle between the Monster and the Ape, the one that is promised by the cover of the DVD case: the superhuman against the inhuman, as the trailer had it.

Yeah, right. Those costumes cost money, brother. You think we’re going to mar them in a fight?

What actually happens is almost laughable anticlimax. Prof. Arnold shoots Thor to save Ken. In the next and last chapter Ernst and the robot go over a cliff into a lake. He doesn’t get to walk away unscratched and neither does the indestructible Metalogen Man. No robot, no metalogen, no thanks. Mankind will not get its race of saviors to end manual labor. “It’s not a failure,” Babs says. “It’s only a stepping-stone to more important discoveries to come.” Science marches on!

Whatever Columbia spent on TMATA was well worth the cost. The studio rolled it out to a few theaters in April. By mid-summer it was everywhere in the U.S. and Canada, often playing several theaters simultaneously in large cities. December saw it still going strong. Newspaper ads give showings all through 1946, and 1947, and through October 1948.

Robert Lowery (Ken) went on to star in multiple b-movies and serials, played Batman in 1949’s Batman and Robin, and spent the next two decades in television roles. Ralph Morgan (Franklin Arnold) was at the end of a long career that started before WWI; he was big enough a name that newspapers reported his taking this, his first serial role. Both George McCready (Prof. Ernst) and Carole Mathews (Babs) were relative newcomers but soon became familiar via dozens of appearances in tv and movies.

And then there’s Willie Best. He played Prof. Arnold’s chauffeur and man of all work, Flash. The veteran black actor was barely older than Mathews but already had over a hundred roles to his credit, starting with the early unbearably racist moniker Sleep ‘n’ Eat. Flash, a sardonic reference to the stereotypical slow and lazy Negro, has no real part in the plot; he’s comic relief. Frightened of the robot he refers to as “rabbit,” always threatening to run away if violence starts, and mangling his words, the character is a vestige of a disgraceful past. You can only get a feeling for how badly black characters were ordinarily portrayed if you believe me when I tell you that Flash is a distinct step above the usual minimum. Flash gets considerable screen time, accompanies Ken into danger despite his protestations, and actually saves the day in one episode by managing to phone for help while tied up – getting knocked unconscious for his valor. His talent was recognized: he also received screen credit for films at majors like Warner Brothers and Paramount in 1945, something none of the others achieved.

Robot serials would return when television came begging for programming. Many stations used serial episodes as daily fodder for kiddies and they also endlessly played movies made from abbreviated serials. TMATA wasn’t one of them, lost and almost forgotten to time. But if you want to see a guy in a robot suit stand up and slowly shuffle across a room, it’s well worth the four hours of time you put into it. JK. Be glad I took the hit for you.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Mechanical Man, Inc. His epic history of robots, Robots in American Popular Culture, is scheduled for a Summer release.

Tik-Tok does show up in 1985’s “Return to Oz” —

I love these pieces. They’re the perfect anodyne for an age in which I’m constantly asked (by machines, no less!), “Are you a robot?”