The Golden Age of Science Fiction: The 1973 Nebula Award for Best Short Story: “When it Changed,” by Joanna Russ

|

|

Steven Silver has been doing a series covering the award winners from his age 12 year, and Steven has credited me for (indirectly) suggesting this, when I quoted Peter Graham’s statement “The Golden Age of Science Fiction” is 12, in the “comment section” to the entry on 1973 in Jo Walton’s wonderful book An Informal History of the Hugos. You see, I was 12 in 1972, so the awards for 1973 were the awards for my personal Golden Age. And Steven suggested that much as he is covering awards for 1980, I might cover awards for 1973 here in Black Gate.

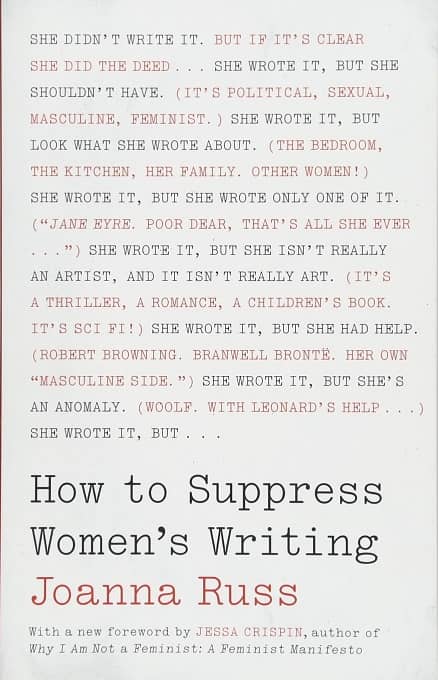

Joanna Russ (1937-2011) was a playwright, critic, and a very important writer of nonfiction and fiction, that latter primarily SF. She was one of the first prominently “out” Lesbians in the SF field, and perhaps the leading feminist voice in the field during much of her lifetime. She was a favorite writer of mine, especially for short fiction such as her Alyx stories (including “The Second Inquisition”), “Nobody’s Home,” “Souls,” “My Boat,” and many more. She also wrote several strong novels, most famously The Female Man. Her best known and most significant extended critical work might be How to Suppress Women’s Writing. Her writing career was hampered late in her life by a long illness. She won the Hugo Award in 1983 for “Souls,” and the Nebula Award in 1973 for “When It Changed.”

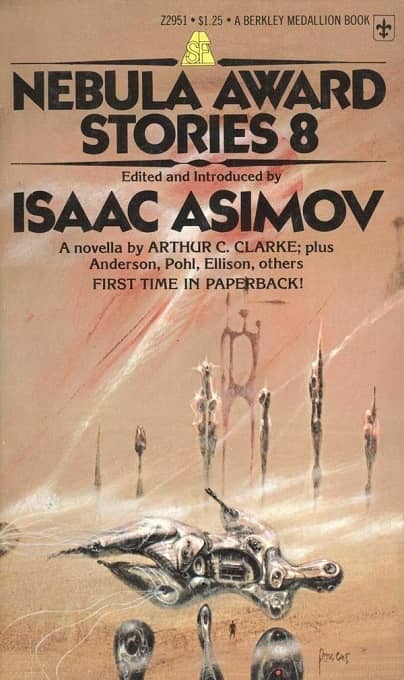

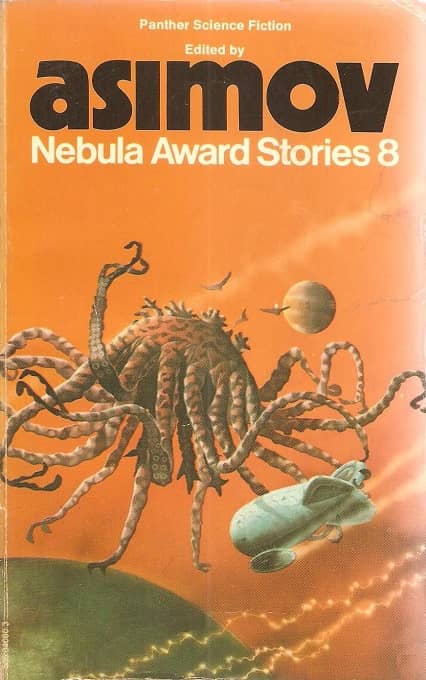

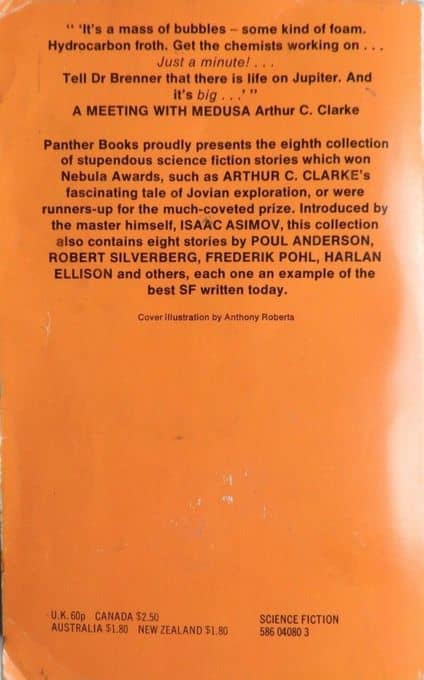

In 1972 I began reading SF from the adult section of the library – that’s why it’s my Golden Age, really! – and one thing I discovered there was the Nebula Award anthologies, published each year and featuring the previous years Nebula winners in short fiction, and a few more nominated stories. I read them all out of the library, and eagerly awaited the appearance, in 1973, of Nebula Award Stories 8, edited by Isaac Asimov. The Nebula winner for short story was “When it Changed,” by Joanna Russ. I read it, and I thought, “So, a planet inhabited by women, and the men show up. I’ve seen that before. What’s the big deal?”

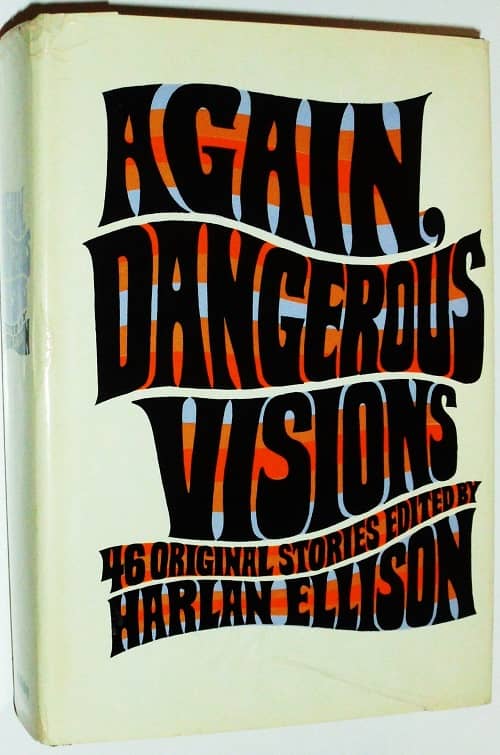

One of the first books I received for free when I joined the Science Fiction Book Club, late in 1974 I believe, was Again, Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison. I reread “When It Changed” at that time, along with Russ’s afterword, and I understood it a bit more, and I saw the anger and loss at the center of the story, but I still didn’t really get it.

It took rereading it much later, as an adult, to come much closer to getting it, and to see how excellent a story it really is. The story is told in a bitter first-person rush by Janet, who is being driven by her wife Katy along with her daughter Yuki to a momentous meeting with a group of male humans from Earth, who have rediscovered the planet Whileaway after 600 years. A plague on Whileaway killed all the males, and they have established an all-female society, with non-parthenogenetic reproduction (the children share genetic material from two parents), and are getting along successfully, given the problems of an isolated colony world with an initially modest population. And now it will all change, whether or not they want it to.

|

|

What is excellent about the story is the characterization – in a very brief space – of Janet and Katy and Yuki and some of the other characters; but more importantly the subtle including of details about this society. It is not a stereotypical gentle female utopia – it is no utopia at all. It is not a copy of traditional male societies. Janet has fought three duels, killing her opponent each time. Life is hard and farm-centric. But it’s their society, and a society they are trying to make better. And now it will all be gone.

It’s still not my favorite short story of 1972, not even my favorite story by Joanna Russ from 1972. When I first read Nebula Award Stories 8, my favorite was Harlan Ellison’s “On the Downhill Side.” (I now prefer “When it Changed” to that story, at least.) When I first read Again, Dangerous Visions, my favorite story was James Tiptree, Jr.’s “The Milk of Paradise,” and that’s still very close to my favorite of that year.

|

|

When I read other stories of 1972, I encountered another Tiptree story, “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side,” and I think that’s truly brilliant as well. And I also encountered another Joanna Russ story, “Nobody’s Home,” which is one of my two favorite Russ stories (with “The Second Inquisition,”) and these days either that or one of the Tiptree stories I mentioned is my choice for the best story of 1972. But “When It Changed,” I see from my older perspective, is also a great story, and a very significant and influential one; and it is certainly a worthy Nebula winner.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a look at the work and awards of Kelly Freas. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s articles here.

I thought that Ms. Russ succeeded both with story and with polemic in “When It Changed”, though I did not get to it (or to Again, Dangerous Visions) until a few years after my 12th year (which was also 1972). The poignancy of how the Whileawayans simply cannot explain to the Terrans their apprehensions over being welcomed back to “full” man-kind just lingered with me, long after finishing it.

> The poignancy of how the Whileawayans simply cannot explain to the Terrans their apprehensions

> over being welcomed back to “full” man-kind just lingered with me, long after finishing it.

Eugene,

That’s a marvelous teaser for the story. You’ve sold me. I will have to dig it out tonight.

John,

If you read “When It Changed”, please let us know what you think of it.

Rich, you were a much more advanced reader than I was at 12. I turned 12 three days after Kennedy was assassinated, which was near the end of 1963, so 1964 is really my Sense of Wonder reading year. I spent most of it reading everything I could find by Robert A. Heinlein. And those were mostly his juveniles at my Jr. High library. I might have discovered the Winston Science Fiction series by then. I also found Andre Norton books too. This was before I discovered anthologies and the digests.