Hither Came Conan: Dave Hardy on “Vale of Lost Women”

Welcome back to the latest installment of Hither Came Conan, where a leading Robert E. Howard expert (and me) examine one of the original Conan stories each week, highlighting what’s best. Dave Hardy is the leading El Borak scholar around, and today he weighs in with a fresh perspective on what is pretty much regarded as one of Howard’s worst Conan tales.

Welcome back to the latest installment of Hither Came Conan, where a leading Robert E. Howard expert (and me) examine one of the original Conan stories each week, highlighting what’s best. Dave Hardy is the leading El Borak scholar around, and today he weighs in with a fresh perspective on what is pretty much regarded as one of Howard’s worst Conan tales.

PAIN CRYSTALLIZED AND MANIFESTED IN FLESH: THE VALE OF LOST WOMEN

“She was drowned in a great gulf of pain—was herself but pain crystallized and manifested in flesh. So she lay without conscious thought or motion, while outside the drums bellowed, the horns clamored, and barbaric voices lifted hideous chants, keeping time to naked feet slapping the heard earth and open palms smiting one another softly.”

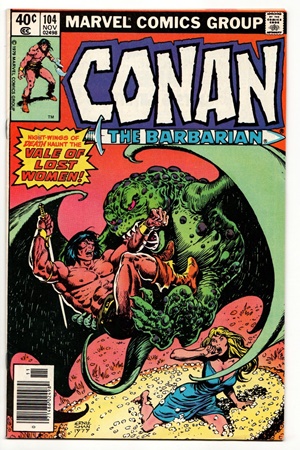

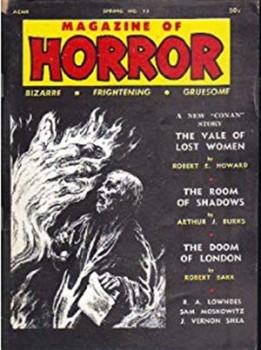

“The Vale of Lost Women” is a neglected part of the Conan canon, scorned even. It was not particularly loved in Howard’s time. Howard wrote “Vale of Lost Women” probably around February 1933. Howard was unable to sell “Vale.” If he submitted it to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales, Wright didn’t buy it. The story was first published in The Magazine of Horror in the Spring, 1967 issue. Compared with such gems as “Queen of the Black Coast,” “Red Nails,” “Black Colossus,” or “Tower of the Elephant,” “Vale” might seem a very slight tale indeed.

And yet there is something primal about “Vale” that defies one to forget it. Despite its crudities and glibness, it taps into dark recesses of fundamental fears and dream logic.

The setting is a village in Kush, the fictional equivalent of Africa. Livia is a young woman from Ophir, one of the civilized countries of Hyboria, in Howard’s setting for the Conan stories. It is a pseudo-European country, inhabited by a fair-skinned folk. She had journeyed with her brother, Theteles, who sought to learn sorcerous wisdom in a remote Stygian city. Instead they were captured by Kushite raiders and came to be captives of Bajujh, king of Bakalah.

The opening is heavily charged with the imagery of rape. Livia is in a state of shock:

“Her whole mental vision, though dazed and chaotic, was yet centered with hideous certitude on the naked, writhing figure of her brother, blood streaming down the quivering thighs. Against a dim nightmare background of dusky interweaving shapes and shadows, the white form was limned in merciless and awful clarity. The air seemed still to pulsate with an agonized screaming, mingled and interwoven obscenely with a rustle of fiendish laughter.”

It’s a nightmare scene, rendered all the more horrific by Howard’s poetic evocation of bloodshed and torture. Howard gives the reader a brief breather before Livia reflects on how little a thing it was to be stripped of her garments by “rude hands.”

The implication and effect of the opening is that both Livia and Theletes were raped. The sexual imagery of blood running down naked, quivering thighs is brutally direct. It might almost be too much for some readers. But there is more to Howard than shock and titillation.

In fact, relief comes in the form of Conan, our familiar hero, entering the scene. Howard liked using secondary characters as viewpoint characters. It pays off well here as we see Conan through Livia’s eyes, revealing him in his strength, swagger, and magnetism.

“So, she watched the white man with painful intensity, noting every detail of his appearance. He was tall; neither in height nor in massiveness was he exceeded by many of the giant blacks. He moved with the lithe suppleness of a great panther. When the firelight caught his eyes, they burned like blue fire. High-strapped sandals guarded his feet, and from his broad girdle hung a sword in a leather scabbard. His appearance was alien and unfamiliar; Livia had never seen his like. But she made no effort to classify his position among the races of mankind. It was enough that his skin was white.”

Note well that when Livia sees white skin, she sees salvation.

That may strike a 21st century reader as shocking, out of place even. In our era it’s more or less an article of faith that racial differences are merely social conventions, and conventions of recent origin no less. Noticing them, let alone appealing to them, is simply inappropriate.

One could certainly argue that ancient peoples were unlikely to look to barbarians, of whatever skin color, for succor. In that light Livia’s impulses are misguided, or worse, a mischaracterization.

That misses the point of what Howard was doing. He wasn’t writing for 21st century bien pensants, still less for fictional inhabitants of the equally fictional Hyborian Age. He was writing for American editors and fiction readers of the 1930s, who sometimes did make assumptions about racial solidarity. And as far as Livia being misguided goes, that was pretty much the point Howard was making. But in the moment, the reader can vicariously feel a ray of hope after the stark horror of the opening scene.

She escapes her confinement and pours out her tale to Conan, expecting him to readily agree to aid her. Instead he gives her no response. Moved to fury at the failure of her appeal to honor and racial solidarity, she makes an appeal on more basic grounds of quid pro quo.

“I will give you a price!” she raved, tearing away her tunic from her ivory breasts. “Am I not fair? Am I not more desirable than these soot-colored wenches? Am I not a worthy reward for blood-letting? Is not a fair-skinned virgin a price worth slaying for?”

Conan’s not so sure. Instead he gives her a run down on the sexual dynamics of Kushite warlords and captive women. “Why should I kill Bajujh to obtain you? Women are cheap as plantains in this land, and their willingness or unwillingness matters as little. You value yourself too highly.”

It’s about as deflating as you can get. Honor, racial solidarity, and even straight up sexual bribery all fail. The barbaric realities and ruthless pragmatism doesn’t have much room for any of that.

There’s a curious inconsistency that appears. After setting the scene with the very strong implication that Livia was raped, she reveals herself to be a virgin. Logically, this revelation jars.

The problem with that analysis is that “Vale of Lost Women” isn’t meant to be logically analyzed. One could explain away the contrast between the implied rape and Livia’s virginity by noting Howard never explicitly says she was raped, or that she remains a virgin in spirit, or whatever clever words would resolve the critic’s problem. But that’s just more logical rationalization, which misses the point. I firmly believe that logic isn’t particularly what readers of heroic fantasy want. They want stories of fear, peril, conflict, courage, and redemption. Writing to be logical is great for grad students, but overrated for fantasists.

The reason the “logical” inconsistency works is that it is required. Had Livia already suffered the last degradation, she’d know better than to appeal to Conan’s honor. The point of the scene is bitter disillusionment. Howard’s contrast between civilized expectations and the brutal realities of barbaric life are at their harshest here.

But Conan has surprises in store. First of all, he is not blind to the fact that Livia is a white woman held captive by blacks. “If you were old and ugly as the devil’s pet vulture, I’d take you away from Bajujh, simply because of the color of your hide.”

But Livia isn’t home free. It suits Conan to accept Livia’s offer regardless. She has staked her ground as a woman willing to do whatever it takes to achieve vengeance. In that spirit he tells her crudely, “Tomorrow night it will be Conan’s bed you’ll warm, not Bajujh’s.”

Conan’s next surprise is that he had no intention of keeping faith with Bajujh, who would be gunning for Conan as soon as it was convenient. Conan’s bargain with Livia is sealed by the fact that in this land, bargains are made to be broken.

Conan duly delivers on his end of the bargain. Again, Howard crafts a nightmare image of unforgettable power.

“A beast-like baying rose, terrifying in its primitive exultation. Through the mob, Conan’s tall form pushed its way. He was striding toward the hut where the girl cowered, and in his hand he bore a ghastly relic—the firelight gleamed on Bajujh’s severed head. The black eyes, glassy now instead of vital, rolled up, revealing only the whites; the jaw hung slack as if in a grin of idiocy; red drops showered thickly along the ground.”

Livia sees Conan bringing Bajujh’s severed head as the price of her virginity. No wonder she flees to the Vale of Lost Women!

Astride a Kushite war stallion, Livia bursts out of Bakalah in maddened flight. Her escape is filled with folkloric images. The image of demon steed and the runaway bride merge into that of a demon bearing away an oath-breaker. By fleeing, she is breaking her bargain with Conan, just as Conan betrayed Bajujh.

That brings up another aspect of “Vale.” The fashion for writing fiction with Joseph Campbell’s myth outline in mind wouldn’t be a thing for another forty years. Nonetheless, Howard nails one of the features of Campbell’s myth cycle quite squarely. Livia’s story becomes a tale of the “call and refusal.”

One of Campbell’s basic patterns of myth is that the hero receives a call to heroism. But for whatever reason the hero refuses the call. This precipitates the hero on the road of trials, where they have to persevere to reach the goal that the call was drawing them to all along. For Campbell, one of the highest achievements of the hero’s journey is an understanding of oneself, and one’s place in the world.

An understanding of the world is what Livia and her late brother lack. The thrust of the story is that she has gone from one disaster to another by leaving the confines of her safe and predictable civilized environment. Her brother Theletes answered one mystical call by traveling to a remote region of Stygia to study rare books of magic. Obviously he didn’t make it.

An understanding of the world is what Livia and her late brother lack. The thrust of the story is that she has gone from one disaster to another by leaving the confines of her safe and predictable civilized environment. Her brother Theletes answered one mystical call by traveling to a remote region of Stygia to study rare books of magic. Obviously he didn’t make it.

In answering the call to adventure, there is no guarantee that one won’t encounter trials, or that one will survive them. A better appreciation of the realities outside of their home might have prompted Livia’s brother to bring more firepower on his trip.

Now Livia has an opportunity to face up to her part in the unfolding events. She took on the role of a hardened character, willing to buy vengeance with her body. In fact, she knows it, and that the slaughter she witnessed was something she helped bnring about. “This was what she had madly hoped and plotted—this ghastly sacrifice was but a just repayment for the wrongs done her and hers.”

But she’s not ready to become that. And one likes her better for it. “Vale” does not celebrate becoming a hardened character, bargaining one’s body for blood vengeance, or casual betrayal. They are simply the conditions of life in this setting.

But there is a price to be paid for opting out. This is Livia’s apotheosis in the Vale of Lost Women. The Vale was the refuge for the women of a tribe whose men had been slaughtered. The women survive there, but at a price. They have become living ghosts, serving a demon.

Arguably, this is no worse a fate than enslavement by conquering barbarians. But that falls into the same trap as Livia. The question posed here it whether it is better to live life, with all its betrayals, cruelties, and sorrows, coming to an end, or to live a half-life forever beyond any of the things that make life worth living. Howard doesn’t pose that as a formal question, but it can be drawn from the nature of the story. And that’s where readers should find such questions, again as “Vale of Lost Women” is fantasy, not a college essay.

If anything, the ending is the biggest weakness to “Vale.” As the lost women prepare to offer up Livia to their demon-god, Conan arrives. In a brief, brutal battle Conan slays the monster. Memorably, he says:

“A devil from the Outer Dark… Oh they’re nothing uncommon. They lurk thick as fleas outside the belt of light which surrounds this world… [T]hey have to take on earthly form and flesh of some sort. A man like myself, with a sword, is a match for any amount of fangs and talons, infernal or terrestrial.”

Conan has met plenty of devils from the Outer Dark and he’s not impressed. It’s over the top, but who really wants subtlety in a pulp Sword & Sorcery adventure?

Rescued again, Livia offers contrition for her broken bargain

“I ran away from you. I planned to dupe you. I was not going to keep my promise to you. I was yours by the bargain we made, but I would have escaped from you if I could Punish me if you will.”

Conan releases Livia, calling their agreement “a foul bargain.” He adds, “The ways of men vary in different lands, but a man need not be a swine, wherever he is.” Conan tells Livia he will arrange for her to return home. Embarrased by her tears of gratitude, he tells her, “Haven’t I explained you’re not the proper woman for a war-chief of the Bamulas?” It’s glib, perhaps too glib, but after the sustained nightmare horror of the preceding pages, perhaps a little glibness is welcome.

There is a growing tendency to criticize the trend of nihilism in current day fantasy. I have no strong opinion on the matter as my reading tends to be of stories from the pulp era. I will say this, Howard depicts a world where casual brutality and unpredictable violence are common. It is a world where treachery is the norm, and battle is a way of life. And yet, a man need not be a swine in that world.

It’s not exactly a new insight, Raymond Chandler said as much when he wrote of mean streets that man must go down. It is an insight worth cherishing.

“Vale of Lost Women” doesn’t stand in the top rank of Howard’s Conan tales. Some might say it is the worst. But best and worst are relative. In “Vale”, Howard’s prose crackles with poetic lyricism, even at the tale’s grimmest moments. The story, so crude and harsh outwardly, rests on a foundation of myth springing from mankind’s basic fears and needs. By any standard “Vale of Women” is a memorable tale that draws in a reader with furious intensity and edge-of-the-seat suspense. If this is Howard at his worst, then he has earned his accolades.

From the Dusty Scrolls (Editor comments)

L. Sprague de Camp, in his Dark Valley Destiny, says that this is one of three stories (along with “The God in teh Bowl” and “The Frost Giant’s Daughter”) quickly written and sent off to Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright, after the publication of “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Except, there is no record of “Vale” having been sent to, or rejected, by Weird Tales. Or anywhere else. REH scholar Patrice Louinet also believes it was submitted for publication (I don’t know when he believes it was written).

David C. Smith, in Robert E. Howard, A Literary Biography, asserts that the story was written in early 1933, right about the same time as “Rogues in the House.” It is a fact that it didn’t appear until being included in the Spring, 1967 edition of Horror Magazine.

Olivia bravely rescued Conan in “Iron Shadows in the Moonlight,” In “Pool of the Black Ones,” Sancha does get shaken into some fortitude and awakens the pirates, gives them their swords and sends them towards Conan. While Livia has certainly suffered terribly in this story, the only spine she shows is crawling into Conan’s tent and asking him to rescue her. She never ‘steps up.’

In the last post, I commented on the moral and ethical questions of Conan’s actions in “Pool of the Black One” and also in “Rogues in the House.” Here, he dismisses betraying and slaughtering his new ally and the chief’s followers.

“Truces in this land are made to be broken. He would break his truce with Jihiji. And afte we’d looted the town together, he’d wipe me out the first time he caught me off guard. What would be blackest treachery in another land, is wisdom here.”

Again – I’m going to say that Conan’s morals/integrity/honor/ethics/whatever, are certainly worth some critical examination and discussion.

Having just read Conan’s fierce struggle in “Xuthal of the Dusk,” his fight with an obviously Lovecraftian-creature is absolutely ho-hum:

“A devil from the Outer Dark…Oh, they’re nothing uncommon. They lurk as thick as fleas outside the belt of light which surrounds this world…A man like myself, with a sword, is a match for any amount of fangs and talons, infernal or terrestrial. Come, my men await me beyond the ridge of the valley.”

He’s bored!

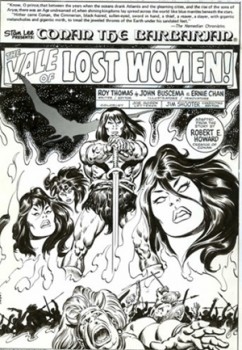

Roy Thomas and John Buscema adapted this tale for issue 104 of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian.

Prior Posts in the Series:

Here Comes Conan!

The Best Conan Story Written by REH Was…?

Bobby Derie on “The Phoenix in the Sword”

Fletcher Vredenburgh on “The Frost Giant’s Daughter”

Ruminations on “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Jason M Waltz on “The Tower of the Elephant”

John C. Hocking on “The Scarlet Citadel”

Morgan Holmes on “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

David C. Smith on “Pool of the Black One”

Up next week, we go off track to talk about Dark Horse’s “Iron Shadows in the Moon” graphic novel.

Dave Hardy is a former member of the Robert E. Howard Press Association and has written for REH: Two-gun Raconteur and The Cimmerian. His novels Crazy Greta and Palmetto Empire, as well as several western stories, are available from Rough Edges Press. He lives in Austin with his wife and daughter.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he will be in the anthology of new Solar Pons stories coming this Spring.

A good argument for the tale’s merits, while highlighting one of its major weaknesses–Conan’s casual dismissal of the eldritch horror, which really has to be more Howard’s fatigue with such rather than his hero’s. This note just rings false.

I know, I know… “Howard wrote it, so it can’t be!” But I’m sorry, even God had his off days. (The seventh, reportedly.) But seriously, Conan’s usual response to such, both earlier and later in his recorded career, is a superstitious dread–even as he (more often than not) springs into action. The “all in a day’s work” comment seriously undercuts everything the guy just did! Perhaps we should be charitable, and see it as Conan trying to convince HIMSELF he didn’t just have a really close shave–or else write it off as Livia’s PERCEPTION of his attitude. After all, she’s been wrong about him before!

Which brings me to what in my view is the other big problem with the story: Livia as the POV character. There’s nothing wrong with a feminine viewpoint as such, but hers makes the tale a soft-porn bodice ripper. In the two most infamous instances of Conan displaying less than honorable intentions towards women, Livia stands (grovels?) in a (very) dark shadow to Atali.

Thanks: a nuanced essay on a difficult (repellent) text. However, I think the ‘devil from the outer dark’ line is probably the key to Howard’s entire canon. Man might be alone in an uncaring universe but he is the hunter not the hunted. Howard expressed the same sentiment in the narrator’s voice in other stories, especially Beyond the Black River (‘But fear had fought for it when it slew its other victims and Conan was not afraid. He knew that any being clothed in material flesh can be slain by material weapons, however grisly its form may be.’) It is this sentiment that makes Howard genuinely enjoyable, distinguishing him from HPL and CAS in this regard.

That is kind of an ‘out of place’ story for the Conan series, something to be expected more of a ‘pastiche’ later one but legit REH. It’s good but something is a bit ‘off’ in that.

IMO its a story idea he was going to use for another horror story but put Conan in it. Ironic, considering some of his stories were turned into Conan stories – “The Flame Knife” my favorite of those. The feeling is more of something I’d expect Kull to deal with.

I’ll add the Dark Horse adaptation had a young Conan sitting on a wall just out of sight listening to priests talk about cosmology – and some of the stuff was put in. That was a neat toss the ball way in the air literary explanation for how the ‘Barbarian’ Conan knew such things.

Real life has been pretty hectic lately, so I’ve been trying just to keep up. I meant to include an Editor’s comment on the source of this story possibly being the real-life story of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was captured by Indians.

Howard talked about that tale in some length in a letter to either Lovecraft or Derleth. I don’t have my references handy.

I’ve heard another interpretation of the opening to this story, but just as horrifying. This view is that Theletes has just been castrated and Livia has been made to watch as her brother is tortured to death. Livia herself is going to be Bajujh’s personal treat.

Interesting analysis of demons in the cosmology of Conan’s world. Thanks for the post!

Castration and torture was how I’ve always interpreted it, as well. Especially in light of Livia’s virgin comment . . .

Well-examined, Dave! And while this “readers of heroic fantasy … want stories of fear, peril, conflict, courage, and redemption.” is outstanding, I’d say a little logic added to that mix never hurts.

Regarding this particular tale, I appreciate Conan’s comment on not being a swine, but it does ring slightly hollow all things considered.

Great job, Dave. You had one of the more difficult Conan stories. While it’s not one of the best Conan stories, I think, as you’ve pointed out, it does have its merits.

Say what you will about the story, but that Marvel adaptation in CtB#104 was one amazing issue. LEGEND!

Nice in depth analysis. Great way to bring in one of the stories which tends to get overlooked so often. I am with Scott and John on the interpretation but that’s what’s great about such stories, they let you draw your own conclusions and don’t spell it out. I would love to have been a fly on the wall listening to contemporary readers of The Magazine of Horror’s interpretations in 1967…

Wow, thank you for this essay, to everyone involved. not to say it’s better then most, but this one shows off what i expected from this series as to why even with shortcomings these stories have stayed the test of time. well written and thoughtful, i really appreciate the thought put into this, and look forward to more of this fantastic series. well done to all.