A Rare and Powerful Book of Magic: Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke

I’ve gotten used to being a decade or two behind the times. I just got Netflix a few weeks ago, I don’t have a cell phone, and I still cling to some vestigial regard for the political and civic institutions of my native land. Yeah, I know – I’m a real museum piece, sure to be coming soon to a display case near you, right next to a stuffed Neanderthal skinning a rabbit with his teeth.

So when I decided that the next book I read would be something recent, and having plucked it from THE PILE, I wasn’t distressed – or even much surprised – when I glanced at the copyright page and saw that this “new” book’s date of publication was 2004. 2004! There are tech billionaires who were in kindergarten then. (Heck, there are tech billionaires who are in kindergarten now.) So much for recent.

But none of that matters, because that not-nearly-as-new-as-I-thought-it-was book, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, is, without qualification, one of the greatest fantasy novels I’ve ever read, and I started reading them when Richard Nixon was president.

[Click the images to embiggen.]

Mr. Norrell

Set in England at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, Clarke’s book tells of the odd friendship, bitter rivalry, and ultimate reconciliation of the nation’s only two practicing (as opposed to merely theoretical) magicians, who are instrumental in restoring magic to the land after three centuries during which the arcane art had practically vanished from Albion. It is an incredibly rich book that contains multitudes, by turns whimsical, bleak, arch, terrifying, satirical, poetic, tragic, mystical, stirring, suspenseful, romantic, eerie… sometimes all on the same page. It is also very funny; more than once Clarke had me laughing out loud with her cunning, perfectly timed and constructed jokes. I will not deprive you of the pleasure of discovering the best one for yourself, but you’ll know it when you find it; the punchline is “Scotland.”

Jonathan Strange

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell has almost too many virtues to enumerate, so I will content myself with mentioning only two — style and substance. That should cover just about everything.

Clarke has chosen not just to set her book in the early eighteen hundreds, but to write it as if it itself is a book of that era, in measured, mannered, ironic, highly civilized prose that Jane Austen herself would have recognized and appreciated. Not every writer can pull this sort of thing off; when it doesn’t work, it’s highly embarrassing, like Keanu Reeves in a period movie. When it does work, though, it can elevate a book to a higher plane than it could have otherwise occupied. In Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, it works. Clarke’s Faux-Regency diction is never false or fussy, chiefly because she doesn’t overdo it or push too hard. The narrative voice so successfully transports you to another time and place that, turning the pages, you feel as if you’re sitting on a velvet-upholstered Louis XVII sofa, reading the book by candlelight.

Jane Austen

The story that Clarke tells is often quite dark, but the darkness never feels oppressive because the tale is continually illuminated by the brilliant flashes of wit that gleam from every page. Even when the situation seems most hopeless, the graceful, cultured style reassures you that in the hands of such a restrained and reasonable guide, ultimately nothing very terrible is going to happen. It allows you to hold on to the hope necessary for negotiating the book’s grimmer passages.

This deliberately antique style is ideally suited to Clarke’s purposes, and in speaking of it, musical metaphors (just like invoking Jane Austen) are inescapable. Reading Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is like spending an evening listening to elegant, expertly played Haydn, his string quartets or one of the “London” symphonies… if Haydn’s notes had the power to summon storms, raise the dead, and compel stones to speak.

Joseph Haydn

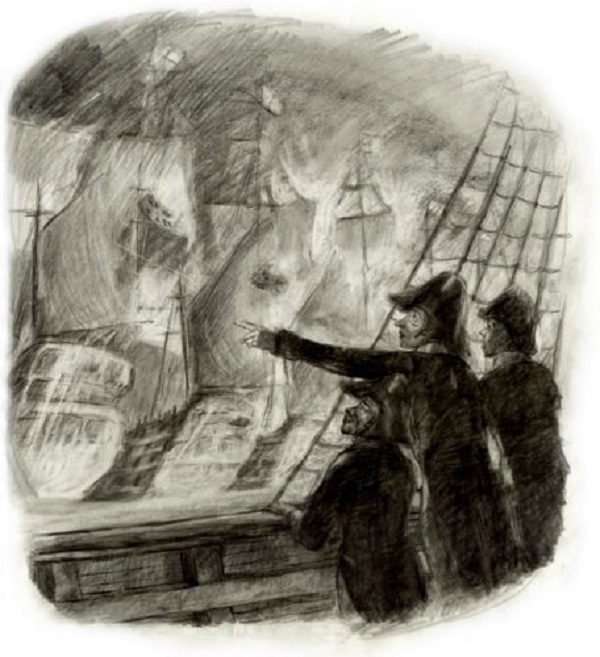

All of these amazing things and more happen during the course of the story, which spans just a little over ten eventful years. The novel is packed with extraordinary incidents – the statues of York Cathedral come to life and resume centuries-old quarrels (and reveal a murder that had taken place in the church five hundred years before); French ships are blockaded in their port by a phantom fleet conjured out of rain; people walk in and out of mirrors; shocking crimes are committed and concealed; the epic battle of Waterloo is fought and won with means mundane and magical; whole cities are transported from one continent to another and back again; politico-magical factions form and clash in the press in battles more merciless than any between the French and British Empires; the King of England is assaulted by the invisible agent of another realm; a pillar of impenetrable supernatural darkness engulfs Venice; the immemorial intercourse between England and Faerie is reopened after centuries of silence and the earth itself awakens and calls out to any who can hear.

The Phantom Blockade

All of this is effected through a cast of vividly realized characters, chief among them Mr. Gilbert Norrell, the first true English magician in centuries, stiff, awkward, pedantic, cautious, unsocial, yet desperately lonely and yearning for friendship without even realizing it, and Jonathan Strange, warm, radical, practical, impulsive, bold, touchy, lonelier than he would like to admit, two men who are ultimately less rivals than necessary and complementary aspects of the same personality, as they eventually come to understand.

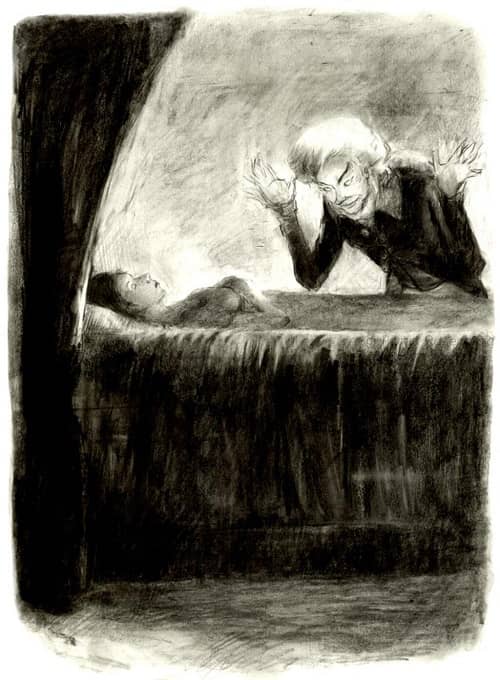

Supporting, opposing or merely looking on in amazement at all this are people like Henry Lascalles, whose aristocratic indolence and hauteur mask a psychopathic violence; the Duke of Wellington, a man as adept at his deadly brand of sorcery as Norrell and Strange are at theirs; Stephen Black, an ex-slave who endures undeserved misery only to come into a startling and unexpected glory; Norrell’s servant John Childermass, outwardly cynical yet tirelessly working to restore to England its true ruler, John Uskglass, the lost and legendary Raven King, who is the fount of all English magic and the shadowy figure that looms over the whole story; Vinculus, a sham street magician whose shabby exterior conceals a numinous power and an extraordinary secret; Emma Wintertowne, a blameless girl brought back from the dead into a life worse than death; Arabella Strange, strong-willed, commonsensical, understanding her husband better than he does himself, whose beauty inadvertently imperils her very soul; and, most memorably, the Gentleman with the Thistle-Down Hair, an inconceivably ancient and powerful and malevolent inhabitant of Faerie whose capricious favor is just as terrible as his wrath, and whose sinister whims provide the mainspring for the story’s action after he is foolishly summoned to this world by Mr. Norrell to aid in a bit — a rather large bit — of magic. Oh yes… Lord Byron makes an appearance too. In this company, the poetic genius and flamboyant sinner almost seems a mundane sort of person.

Susanna Clarke

All of this in a book that some have complained is slow! “It’s boring — nothing happens,” some have said. (Really! I’ve seen it in online reviews. Take my advice — if you want to keep your temper, don’t read those damn things… except this one, of course.) I can only suppose that such people’s definitions of “nothing” and “boring” differ from mine.

Maybe they just don’t like footnotes; Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell admittedly has a lot of them. Clarke uses these footnotes — some quite brief, many rather long — to expound and expand on the imagined magical history and literature that her book is grounded on. I found them wonderful and positively looked forward to them, which was a big change from the last heavily footnoted novel I read, David Foster Wallace’s postmodern doorstopper, Infinite Jest. In that book, Wallace used footnotes to impede and derail his own narrative, as if to chastise and punish anyone foolish enough to want an actual story; Clarke, on the other hand, generously uses her footnotes to give her readers even more story, stories within stories. Perhaps she thinks that in the end stories are all we have, and so we can never have too many of them; in any case her old-fashioned notion that the primary job of a book is to delight its readers means that I’m with her on this one.

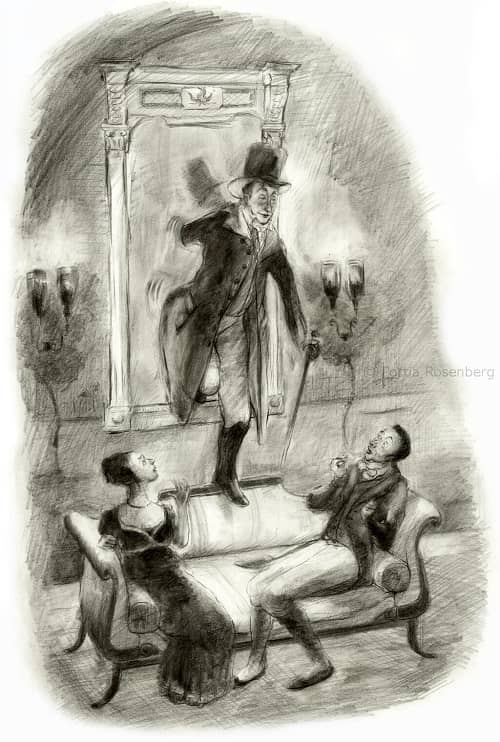

Jonathan Strange pays a call

Certainly Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is in its way a restrained book, and if you believe that nothing succeeds like excess you may find its low rape and beheading quotient (as in none) distressing. But bring a little patience and an awareness that restraint can actually heighten drama and raise the stakes of action and you will discover that this is a book filled to the brim with love and hate, meanness and generosity, knowledge and fear, prophecies and portents, laughter and terror, violence and tranquility, honesty and intrigue, despair and joy, sublime poetry and good English dirt. It has that most precious and most welcome thing (especially when it appears on the last page of a long novel that you’ve given yourself to for weeks and weeks), a perfect ending; when you set a book down with both a tear in your eye and a big grin on your face, you know you’ve spent your time well.

Much of this unique and superb book is concerned with books themselves, primarily ones on magic. Mr. Norrell is an obsessive collector of volumes in his chosen field, and in fact, he buys up virtually every book on the subject in the country, so anxious is he to keep them from falling into the hands of potential competitors. Early on, this leads to a distinction being made between books about magic and books of magic. The first kind, however well done, are common and relatively tame. The second kind are rare and powerful. They are not merely dry, dead histories or barren exercises; you can conjure with them.

The Gentleman and Emma Wintertowne

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, unlike so many fantasies that fill the chain bookstore shelves, is not just one more book about magic; it is a book of magic. If you have not yet read it, don’t let anything hold you back. Open it, enter it, commit to it and let it cast its spell over you. When you emerge breathless on the other side, you will know without a doubt that even at this late date, the roads to Faerie are open, and there is still such a thing as magic in this world.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Astounding Life of John W. Campbell.

It is an utterly remarkable novel, the best fantasy of the 21st Century, except I suppose for KA.

I read this while on holidays in Italy around ten years ago, and really enjoyed it. I’ve said elsewhere that I always reckoned a big influence was ‘Kingdoms of Elfin’ by Sylvia Townsend Warner – specifically re how elvish temperament is depicted, but having read the latter recently (it’s now available on Kindle) I think – while this may be so – Clarke transcended her influences.

I wonder if she’ll ever write anything else? Some writers have one good book in them, and – this accomplished – they never feel the inclination to produce anything else. Which is their prerogative, of course.

Aonghus, I read somewhere that Clarke’s been working for years on another book, set in the same milieu, but chronologically earlier…but she suffers from chronic fatigue syndrome, which of course makes things very difficult. If she ever finishes it, I’ll be there the day it’s published!

There’s also the related short story collection Ladies of Grace Adieu.

Someday I should reread the book; I’d also recommend the BBC miniseries from a few years back.

My brother really enjoyed the miniseries.

I have not read the book and, after the first two episodes of the BBC series failed to hook me. But this review has really kindled my interest… on to the TBR pile it goes!

After finishing the book I started watching the miniseries. It hasn’t hooked me either; I think it would be difficult to follow if you hadn’t read the novel. It does seem very well cast, though.

I love this book immoderately. It’s on my personal list of top 10 fantasy novels of all time. Possibly top 5. On the story level, it’s endlessly inventive and emotionally gripping. On the craftsmanship level, it breaks so many ostensible rules, so flagrantly and blithely, with wild success every time, it’s exhilarating to watch the author walk her tightrope.

When it first came out, Jo Walton said in a blog post that it was what our genre might have looked like if, instead of taking Tolkien as its touchstone and then traveling by way of David Eddings, its touchstone text were Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist, descended by way of Peake’s Gormenghast series. I’d never heard of Mirrlees, but got a copy of her one novel immediately, and yes, it really does feel like a worthy ancestor to Strange&Norrell, just much smaller and weirder.

Lud-in-the-Mist is indeed one of the great fantasies, and richly deserves to be better known. (I’m especially fond of it because it’s about paternal love and sacrifice, not the most fashionable subject these days.) I think there’s a reason that LotR became the pattern, though, instead of Lud or Gormenghast or something like them. I have nothing but respect for Tolkien and his achievement; to imply that it was in any way “easy” is self-evidently absurd. That kind of creation is difficult beyond the imagination of a lesser mortal like me – I’m sure just as difficult in its own way as Mirrlees’ or Peake’s kind of magic. But Tolkien’s mode of fantasy is, I think, easier to IMITATE. It’s the same reason there are five hundred Lovecraft and Howard acolytes for every disciple of Clark Ashton Smith.

The things Lud and Gormenghast demand of readers are not the things that lead to mass appeal. I think the main reason Clarke got so close is that her publisher, disingenuously, marketed Strange&Norrell as “Harry Potter for grown-ups.”

I, too, want to see more good dad stories. There are so many non-toxic forms of masculinity, and everybody benefits when those are in the stories we tell.

I was working in the Borders corporate offices when this book came out and I can honestly say that I never saw so many people so eagerly anticipating a new genre book.

My own interest was cool as the book looked huge and prolix. Besides, who wants to read something new when there’s still so much to read that’s old?

Nobody finished reading this book. Nobody.

I know more people who finished Infinite Jest. An equal number who finished Gravity’s Rainbow.

So these comments pretty much knocked me over. Up until now I had what I would have deemed unassailable evidence that this book was all but unreadable.

Maybe I should read the thing. I have it, of course. Just because I didn’t want to read it didn’t mean I didn’t get one.

And if that makes sense to you then maybe you have as many books as I do.

Loved this book, along with her collection of short stories.

I got the book as an advanced readers copy and had just begun to read it when I learned that I had an opportunity to interview Ms. Clarke. I had one week to finish the book and prepare for the interview (as well as re-read her short stories).

The interview ran in two parts over of SF Site.

Part I: https://www.sfsite.com/02a/su193.htm

Part II: https://www.sfsite.com/02b/sl194.htm