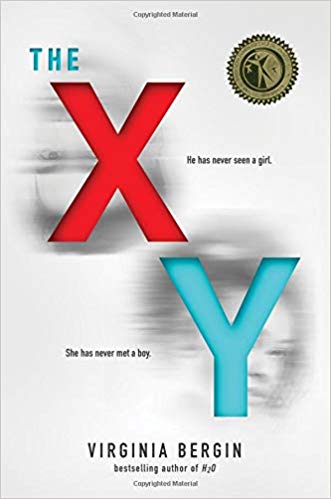

Gender Boundaries Crumble in YA: The XY by Virginia Bergin

River drives her horse and cart through the woods as night falls. But when she sees a body lying in the middle of the road, her first emotion isn’t fear. It’s surprise.

The body doesn’t look like any she’s ever seen. It’s clearly human, but it has no breasts. There’s hair on its face, and a strange lumpiness rises between its legs.

It’s an XY. A male.

River has never encountered an XY before. Boys and men all live in hermetically sealed Sanctuaries where they won’t contract a lethal virus. The rest of the planet has been given over to women, who are immune. Any boy or man who leaves one of the Sanctuaries dies within 24 hours.

When River rouses the XY to consciousness, he attacks her, steals her knife, threatens to kill her, and eats her food without permission. River has never encountered anyone who would behave so badly before.

The XY – his name is Mason – says he’s been on the run in women’s country for five days. But only now does he fall ill. Losing his faculties, he releases her once again.

Watching him writhe on the road, River knows this male creature – this boy named Mason – is going to die. He knows it, too. He said as much to her.

She knows the humane thing to do. Her community’s code requires her to put him out of his misery. She’s given mercy to injured animals before.

But she just can’t bring herself to draw her blade across his neck. He’s a human being.

It takes three hours, but she carts Mason back to her village. The appearance of the first XY to survive the virus for more than a day reveals rifts in this community of women. Some race to heal him. Others want him to die. Caught in the middle, River finds herself lying for the first time in her life. Everything in her safe existence starts to unravel.

Virginia Bergin’s The XY is a post-apocalyptic puzzlebox that raises important questions about gender, sexuality, and toxic masculinity. A provocative thought experiment in the same vein as classic feminist science fiction like Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, the book was awarded the prestigious James Tiptree Jr. Award from Wiscon, that venerable grandmother of feminist Sci Fi / Fantasy conferences. By building a fictional world in which women and girls might not be completely safe, yet need not fear men and boys, Bergin illuminates the twisted beliefs that permeate our real world.

Yet Bergin does not blame Mason for his disturbing aggressive behavior. Rather, she critiques patriarchal cultures that victimize boys themselves. As such, the book’s message aligns with contemporary findings of the American Psychological Association. She also holds out more hope for men and boys than another predecessor in the same lineage: Sheri S. Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country. To judge from some of the rather reactionary reviews The XY has received on Amazon, however, the book may still be ahead of its time.

Bergin’s prose also demonstrates several unconventional and interesting literary choices. For instance, the narration shifts from third-person in the first chapter to first-person in the second, which dramatically heightens the tension and catapults the pace forward. She also employs bold font, strikethroughs, italics, and underlining in idiosyncratic and novel ways. The only word for her prose is inventive. Sometimes it can be downright hilarious.

The XY might be marketed to teens, but adults’ interest in its deeper philosophical questions might make us its more natural audience. Originally published in the United Kingdom as Who Runs the World in 2017, Sourcebooks Fire released the novel under the new title on November 6, 2018. Bergin is also the author of the H2O duology.

The XY is 327 pages, priced at $17.99 in both hardcover and digital formats.

Elizabeth Galewski is the author of The Wish-Granting Jewel, a fantasy novel, and Butterfly Valley, a tale of travel and transformation based on true events. To learn more, please visit her official website at www.elizabethgalewski.com.

If I could have one wish granted, it would be that folks who use “patriarch” in all of its forms like a grenade (it’s easy – just pull the pin and throw!) could know for just five minutes how very hard (and sometimes how very sad) it is to be a father, especially in this culture. Just five minutes.