Goth Chick News: Get Ready, Here Comes Your Summer Reading List

If you live somewhere that, like Chicago, has been experiencing temperatures incompatible with human life over the past couple months, then thinking about a lounge chair, a book and an umbrella drink wearing anything less than a Tauntaun skin is pretty darn appealing. And with perfect timing, here comes the 2018 Bram Stoker Award nominees hot off the press from the Horror Writers Association (HWA), providing a categorized list of reading material.

Now all you need is the lounge chair, an umbrella drink and a space heater.

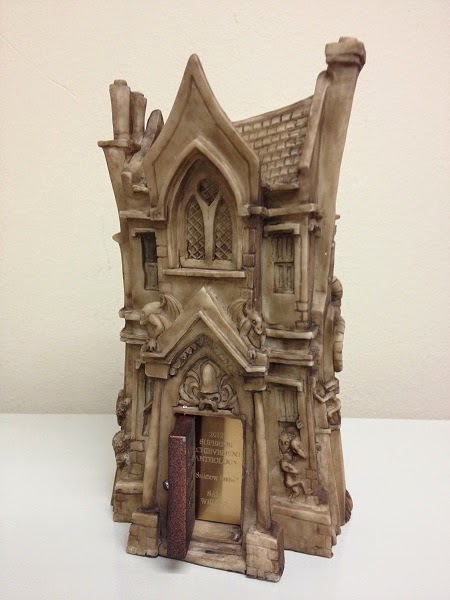

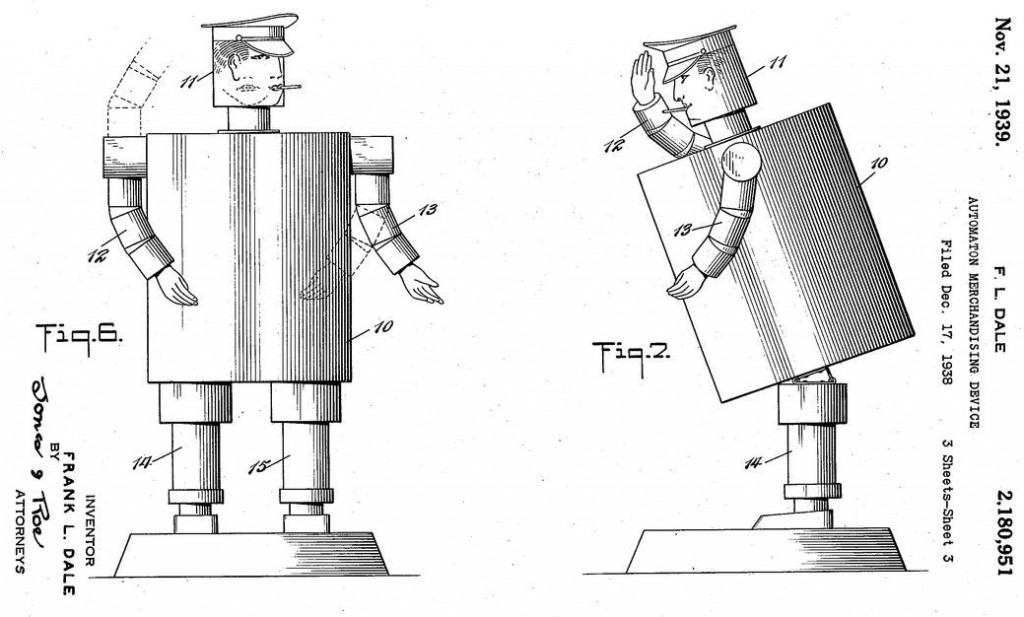

Named in honor Dracula’s spiritual Daddy, the Bram Stoker Awards are presented each year for superior achievement in writing in eleven categories. It is also the coolest physical award ever. I mean, Oscar is just a naked gold guy while the Stoker looks like this:

Previous winners include Stephen King, J.K. Rowling, George R. R. Martin, Joyce Carol Oates, and Neil Gaiman.

The HWA is a nonprofit organization of writers and publishing professionals around the world, dedicated to promoting dark literature and the interests of those who write it. The HWA formed in 1985 with the help of many of the field’s greats, including Dean Koontz, Robert McCammon, and Joe R. Lansdale, and in addition to the Stoker, the HWA is the sponsor of the annual StokerCon horror convention which takes place in Grand Rapids, MI.

So grab a pen Black Gaters and get ready to make your list…