The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Peter Nicholls and The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

|

|

|

Peter Graham is often quoted as saying that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is 12. I was reminded of this quote last year while reading Jo Walton’s An Informal History of the Hugo Awards (Tor Books) when Rich Horton commented that based on Graham’s statement, for him, the Golden Age of Science Fiction was 1972. It got me thinking about what science fiction (and fantasy) looked like the year I turned twelve and so this year, I’ll be looking at the year 1979 through a lens of the works and people who won science fiction awards in 1980, ostensibly for works that were published in 1979. I’ve also invited Rich to join me on the journey and he’ll be posting articles looking at the 1973 award year.

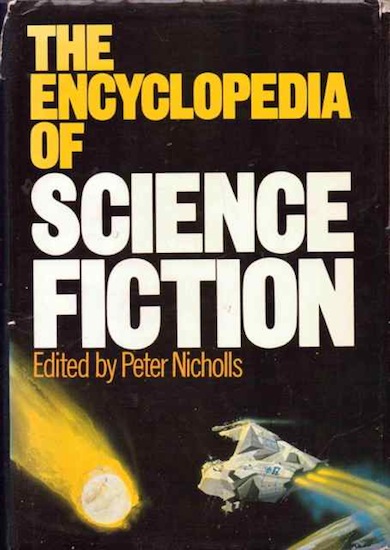

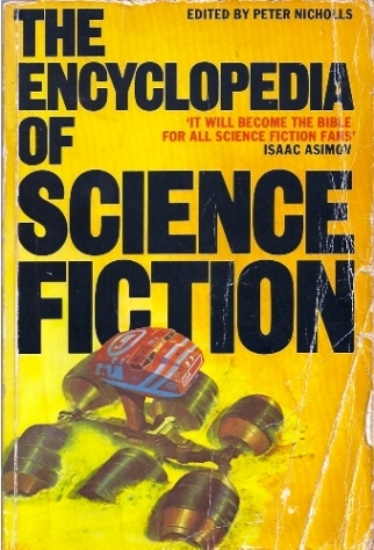

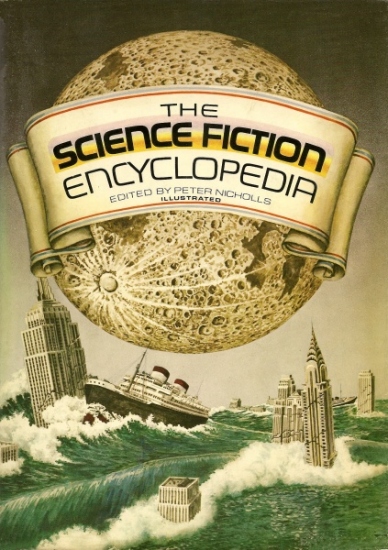

The Best Nonfiction category was not one of the original Hugo categories in 1953, and since its introduction in 1980, when Nicholls won the inaugural award, it has been something of a Frankenstein category, a place where anything that doesn’t clearly fit into another category has been placed. This has resulted in books, websites, comics, podcasts, and music all going up against each other in a chaotic mélange. At various times, the category has been for Related Work, Related Book, and Nonfiction. While the award has not been well defined, it has been a constant on the Hugo ballots since its introduction in 1980. Not only did Peter Nicholls win that first award for The Science Fiction Encyclopedia, he won it a second time for the 1994 expansion with John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction as well as in 2012 for the web-based The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Third Edition, with Clute, David Langford, and Graham Sleight. In 1980, the Hugo Award was presented at Noreascon Two in Boston, Massachusetts on August 31.

The Locus Awards were established in 1972 and presented by Locus Magazine based on a poll of its readers. In more recent years, the poll has been opened up to on-line readers, although subscribers’ votes have been given extra weight. At various times the award has been presented at Westercon and, more recently, at a weekend sponsored by Locus at the Science Fiction Museum (now MoPop) in Seattle. The Best Related Non-Fiction Book category has gone by several different names over the years. It was presented as a one-off award in 1976, when James E. Gunn won it for Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction. It was reintroduced in 1979 and given to Frederik Pohl for The Way the Future Was. Some form of the award has been presented every years since then. In 1980, Peter Nicholls won the award for The Science Fiction Encyclopedia. In 1980, the Locus Poll received 854 responses.

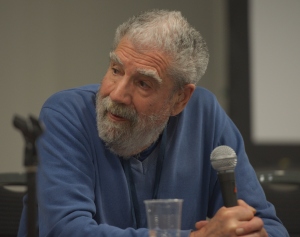

The Pilgrim Award was established in 1970 by the Science Fiction Research Association. Named for J.O. Bailey’s book Pilgrims through Space and Time, the first award was presented to Bailey and recognizes individuals who have devoted their lives to science fiction research and scholarship. The 1980 award was presented at the SFRA Annual Conference held from June 18-21 on Staten Island. Australian author Peter Nicholls (1939-2018) received the award in 1980, the same year that his landmark The Science Fiction Encyclopedia won the Hugo Award for Best Nonfiction and the Locus Award for Best Reference Book.

Nicholls’s Pilgrim Award was not solely for his work on the encyclopedia, but it did honor his several years of research and service to academic science fiction.

Born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1968, he received a Harkness Fellowship that allowed him to study film at Boston University before he headed to Hollywood to help Robert Wise as an assistant on the film The Andromeda Strain. When he finished with that, he moved to London. From 1971 through 1977, he was the first Administrator of the Science Fiction Foundation, a research unit established at the North East London Polytechnic. During his tenure, the Foundation also supervised graduate research work in the field and developed academic syllabi for the teaching of science fiction in the classroom. Nicholls also edited the Foundation’s journal, Foundation: The Review of Science Fiction, from 1974 until 1978.

Under the auspices of the Science Fiction Foundation, Nicholls organized a science fiction symposium in 1975 that included papers by John Brunner, Philip K. Dick, Thomas M. Disch, Harry Harrison, Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert Sheckley, and others.

Nicholls was a frequent contributor of science fiction book and film reviews and criticism to both radio, newspapers, and magazines. He often appeared on the BBC Radio 4 show Kaleidoscope discussing science fiction and supporting his view that stories told for entertainment are still important. Requests for a general overview of the field led him to compile The Science Fiction Encyclopedia.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to discuss Nicholls’s first edition of The Science Fiction Encyclopedia without also discussing its later editions. A much smaller volume with fewer entries and written before numerous of its subjects have died, the book has been superseded by the subsequent works. That being said, looking through the first edition is an interesting exercise.

The first thing that strikes the reader is that while the later editions are text only, even the on-line version (although a CD-Rom version of the 1994 edition does have numerous photos), the first edition is copiously illustrated with photos of authors, stills from films, and reproductions of cover and interior art from through the history of science fiction. While these images tend to be small and the reproduction limited by the technology available in 1979, they do add an extra dimension to the work which is lacking in the later editions.

Opening the volume at random and doing a comparison of an entry between the different editions, such as for author Deane Louis Romano shows a complete rewrite between the 1979 and 1994 volumes with some additional tweaking for the web version (including, after 2011, Deane’s date of death). All three devote approximately the same word count to this admittedly minor author.

Other thematic entries aren’t yet defined in the 1979 book. Alternate History, does not appear in the two print versions of the encyclopedia, except as a header that directs the reader to the entries on Alternate Worlds and History in SF. In the on-line version, the subgenre has its own significant entry, which explores the field’s history, not only recently, back looking at its nineteenth and early twentieth century roots.

Scholarship is in a constant state of flux, which is what makes the current web-based encyclopedia so useful. One author who does not appear in the first edition, but whose importance was recognized by the 1994 book, is Clare Winger Harris, the first woman to publish under a clearly feminine name in the pulp magazines of the 1920s and whose work has been collected in Away from Here and Now.

With the later editions, and especially the on-line version, The Science Fiction Encyclopedia is now little more than a curiosity. It was the first winner of the award, and certainly deservedly so, but it in longer current. All four of the work that competed against it for the Hugo and three of the books that ranked immediately below it for the Locus Award, have retained their utility in a way that this particular edition did not, although it was a monumental achievement for the time and laid the foundation for the books that replaced it.

In its first year, the Best Nonfiction Hugo included two art books, a collection of essays, an autobiography, and the winning encyclopedia. The other works nominated were Wayne Douglas Barlowe and Ian Summers’ Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials, which won the Locus Award for Art or Illustrated Book, the first volume of Isaac Asimov’s autobiography, In Memory Yet Green, The Language of the Night, a collection of essays by Ursula K. Le Guin that was edited by Susan Wood, and Michael Whelan’s art collection Wonderworks.

The other top five non-fiction books for the Locus Award included (in order of finishing) In Memory Yet Green by Isaac Asimov, A Reader’s Guide to Science Fiction by Baird Searles, etc., The Language of the Night by Ursula K. Le Guin, and The World of Science Fiction: 1926-1976, by Lester del Rey.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

My co-worker Clare MacAinsh would dispute the “clearly” (or did you mean “ineluctably”?) feminine nature of Clare Winger Harris’ name. As would famous writer of YA sports books Clair Bee.

🙂

Anyway, Nicholls’ awards are all absolutely merited — the Science Fiction Encyclopedia, in all its forms, is a towering and very important achievement.

The Clute and Nicholls encyclopedia is one of the world’s great reference books. I’ve worn out two copies and a week doesn’t go by when I don’t pull down my big hardback or check the online edition.

As much as I love all 3 editions of The Science Fiction Encyclopedia, I have the same reaction as Mr. Smith to the plethora of illustration in the 1st edition. The lack thereof was my greatest disappointment with the (deservedly awarded) 2nd edition.

In fact, my enjoyment of the illustrations makes me wish to quibble with the attribution of the cover on the right-most image (the version that I own), as the underlying picture of the giant moon flooding Manhattan with its super-tides is a Frank Paul painting, used by Mr. Christensen in his marvelous cover design. Alas, even the venerable ISFDB does not offer Mr. Paul a co-credit!