Vintage Treasures: Space, Time & Crime edited by Miriam Allen deFord

|

|

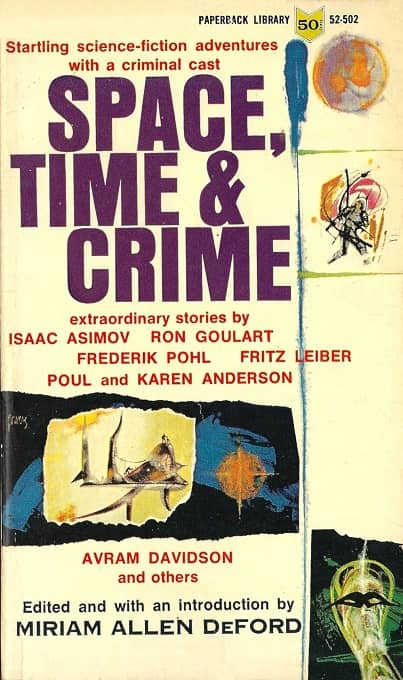

Genre blending these days is very popular. So you have steampunk space operas like RJ Theodore’s Flotsam, SF noir like K.R. Richardson’s Blood Orbit, near-future police procedurals such as Serial Box’s Ninth Step Station, and every conceivable genre mash-up in between. But there was a time when daring to mix genres like science fiction and mystery was exciting and new. One of the first paperback anthologies to try it was Miriam Allen deFord’s Space, Time & Crime, published by Paperback Library in 1964, when I was just six months old. But even then, as deFord rather astutely observes in her introduction, it had been going on quietly in the genre for for time.

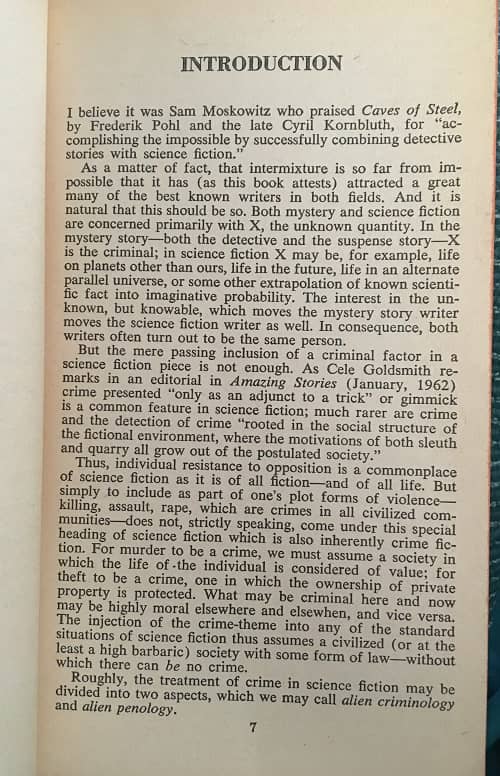

I believe it was Sam Moskowitz who praised Caves of Steel, by Frederik Pohl and the late Cyril Kornbluth, for “accomplishing the impossible by successfully combining detective stories with science fiction.”

As a matter of fact, that intermixture is so far from impossible that it has (as this book attests) attracted a great many of the best known writers in both fields. And it is natural that this should be so. Both mystery and science fiction are concerned primarily with X, the unknown quantity. In the mystery story — both the detective and the suspense story — X is the criminal; in science fiction X may be, for example, life on planets other than ours, life in the future, life in an alternate parallel universe, or some other extrapolation of known scientific fact into imaginative probability. The interest in the unknown, but knowable, which moves the mystery story writer moves the science fiction writer as well. In consequence, both writers often turn out to be the same person.

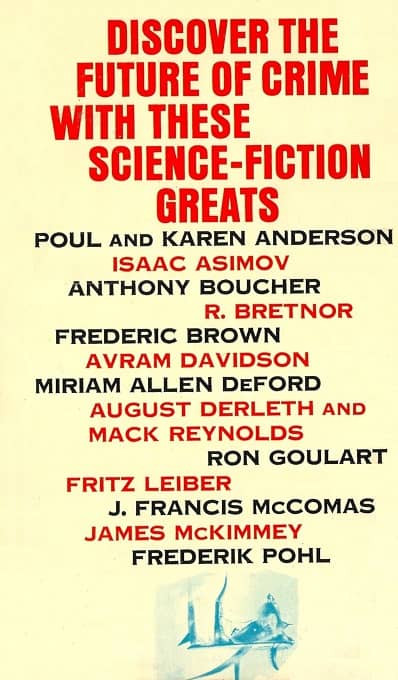

Setting aside that jaw-dropping gaff in the very first line (um, Caves of Steel was written by Isaac Asimov, not Pohl and Kornbluth), Space, Time & Crime is a terrific anthology, with stories from Fredric Brown, Anthony Boucher, Frederik Pohl, Avram Davidson, Ron Goulart, Isaac Asimov, Reginald Bretnor… plus a Solar Pons story August Derleth and Mack Reynolds and a Change War tale by Fritz Leiber. Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

[Click the images for crime-sized versions.]

Introduction by Miriam Allen deFord

“Crisis, 1999” by Fredric Brown (1949)

“Criminal Negligence” by J. Francis McComas (1955)

“The Talking Stone” by Isaac Asimov (1955)

“The Past and Its Dead People” by Reginald Bretnor (1956)

“The Adventure of the Snitch in Time” by August Derleth and Mack Reynolds (1953)

“The Eyes Have It” by James McKimmey, Jr. (1953)

“Public Eye” by Anthony Boucher (1952)

“The Innocent Arrival” by Karen Anderson and Poul Anderson (1958)

“Third Offense” by Frederik Pohl (1958)

“The Recurrent Suitor” by Ron Goulart (1963)

“Try and Change the Past” by Fritz Leiber (1958)

“Rope’s End” by Miriam Allen deFord (1960)

“Or the Grasses Grow” by Avram Davidson (1958)

And here’s the first page of deFord’s intro, which makes fine reading.

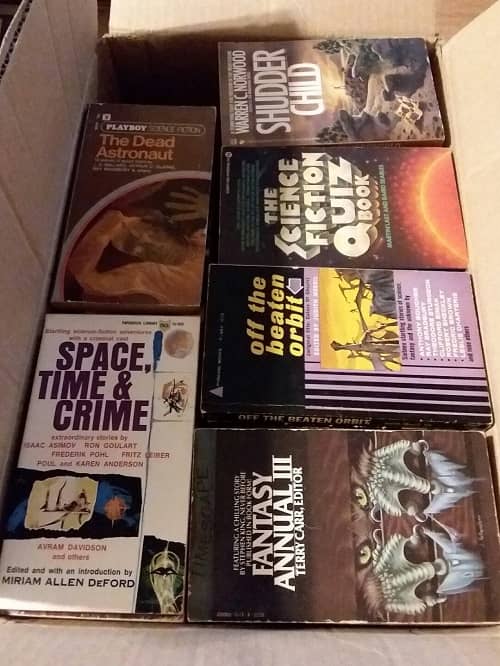

Space, Time & Crime isn’t particularly hard to find. I found a copy in a box of 40 vintage SF paperbacks I bought on eBay for 15 measly bucks, less than 40 cents/book.

Here’s a few pics of the rest of the box, since I know I’m going to get asked about it.

Space, Time & Crime was published by Paperback Library in November 1964. It is 174 pages, priced at 50 cents in paperback. It has been reprinted only once, in 1968, with a new cover by Jack Gaughan. There is no digital edition.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

I suppose that the “impossibility” of crossing genres with sf and mystery is the careful balancing act required, as mysteries are meant to “play fair” with the reader, presenting all the evidence, which means that the sf elements must be acutely described to be “fair” (no using interdimensional portals to solve a “locked-room” mystery without giving a good set of blueprints).

And Ms. DeFord makes a great point about sf culture building inherently having an effect on the whole definition of “crime”. Or “punishment”, as her own story, “The Malley System” (published in Dangerous Visions when she was 79) prefigured Mr. Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange with its “aversion therapy” treatment for violent crimes.

“A Clockwork Orange” was published in 1962. “Dangerous Visions” came out 5 years later. Unless Ms. DeFord traveled back in time, Burgess came up with the idea of aversion therapy first, although since it’s been many years since I read the book, I’m not sure if that’s the name he gave it.

smitty59,

Oops! I must have grabbed the wrong edition (or cross-wired the film date instead). Thanks for the correction!

I would still give Ms. DeFord some props as her method was decidedly more science-fictional (penal sentences served as induced comas with dream loops of the crimes repeated endlessly, for much longer “subjective” experiences).

I’ll be interested in finding out: I just ordered a copy through Amazon. This is the kind of book I’d have ordered from places like A Change of Hobbit, back in the early ’70s, when I had a factory job, no girlfriend, and lived with my folks. Somehow this particular title was never one I found in the backs of other Paperback Library SF books. Thanks, Eugene, for your comment, and John for the review!