Golden Age of Science Fiction: The 1973 Phoenix Award

|

|

|

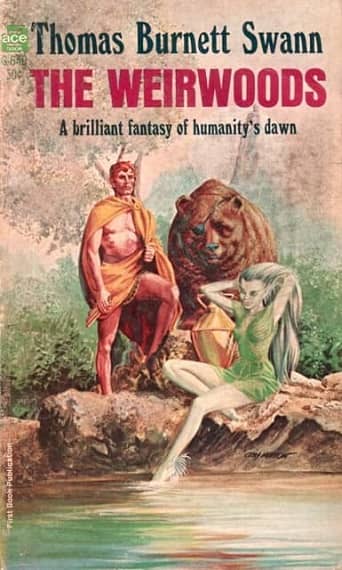

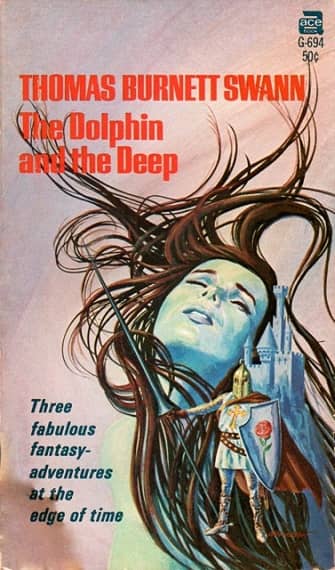

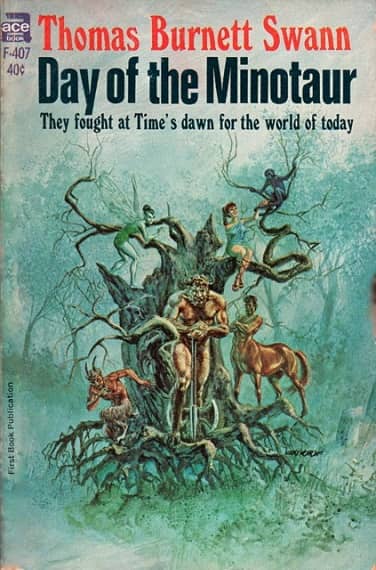

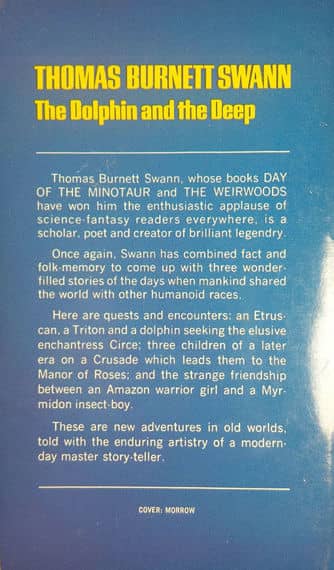

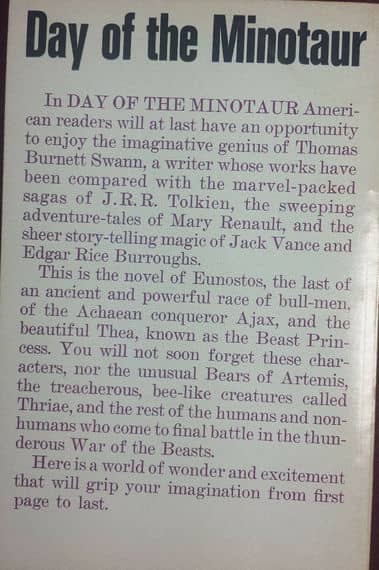

Ace edition covers by Gray Morrow

Steven Silver has been doing a series covering the award winners from his age 12 year, and Steven has credited me for (indirectly) suggesting this, when I quoted Peter Graham’s statement “The Golden Age of Science Fiction is 12″, in the “comment section” to the entry on 1973 in Jo Walton’s wonderful book An Informal History of the Hugos. You see, I was 12 in 1972, so the awards for 1973 were the awards for my personal Golden Age. And Steven suggested that much as he is covering awards for 1980, I might cover awards for 1973 here in Black Gate.

And, indeed, 1972 is when I discovered Science Fiction in the adult section of Nichols Library in Naperville, IL. Mind you, I’d already read and loved The Zero Stone by Andre Norton, and read and kind of liked Robert Silverberg’s Revolt on Alpha C, and read and loved a ton of fantasies such as the Narnia books, The Hobbit, and George MacDonald’s The Princess and Curdie and At the Back of the North Wind. But I found all those in the children’s section. When I was 12 two things happened. In my seventh grade class we were introduced to a variety of books via a huge set of large folded cards, each of which had a substantial extract from a book. You were supposed to read the extract and answer a quiz about it, but the real motive of the developers was to try to get kids interesting in reading the whole of some of these books.

I read a bunch of things – Exodus by Leon Uris is one I recall – but I quickly realized it was the Science Fiction that lit me up. Books I recall reading because of that class include The Currents of Space, by Isaac Asimov; Against the Fall of Night, by Arthur C. Clarke; The Universe Between, by Alan E. Nourse; Time is the Simplest Thing, by Clifford Simak; and Galactic Derelict, by Andre Norton. And, of course, to find those books I had to go the adult section of the library. Where I quickly also found other stuff by those authors, and then other authors, and perhaps more important, anthologies. The Science Fiction Hall of Fame was a revelation. And so were the Nebula anthologies. And Anthony Boucher’s Treasury of Great Science Fiction. So I was hooked forever.

|

|

|

But did I read the great new stuff from 1972? That took a bit longer. But I got around to it eventually, and I’ll get around to the 1973 awards as the year continues. I’ll begin with something pretty darned obscure, however. The Phoenix Award. What is the Phoenix Award? Here’s what the Southern Fandom Confederation Handbook and History page says:

The Phoenix Award was first given out in 1970. The committee-chosen award is given to a pro who has done a great deal for Southern Fandom. Some committees have asked previous winners of the award for suggestions, but this is not mandatory. The form the award takes (as with the Rebel) varies according to committee whim.

The first two winners were Richard C. Meredith and R. A. Lafferty, and Thomas Burnett Swann was the third, awarded at PeliCon in New Orleans in 1973. Don Markstein is quoted as saying

He came to a couple of DSCs, seemed to enjoy himself. He wrote real, real well. A Southerner…. Everybody liked him, everybody liked his writing, so the committee decided it to give it him.

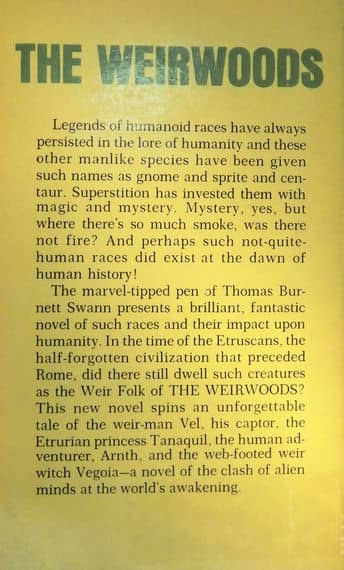

Thomas Burnett Swann was born 12 October 1928. He died in 1976, only 47, of cancer. He was an academic who taught at Florida Atlantic University, and wrote a significant study of the poet H. D. Beginning in the late 1950s he wrote a number of fantasy stories, and eventually a number of novels, including a glut in the last year or two of his life (some published posthumously), most set in a loosely connected alternate history/fantasy of the couple of millennia before Christ. It’s often been noted that his earlier work was better than the later work (especially the last novels, presumably produced at speed after he had gotten sick, perhaps with the intent of supporting his heirs.)

This is a position I endorse entirely. His novels included very noticeably gay subtexts, though only towards the end did this become explicit at all (it’s most noticeable in How Are the Mighty Fallen, which tells explicitly of David and Jonathan as lovers). As such it is widely assumed that he was gay, though I’m can’t find confirmation of that in a quick web search.

I have read all of Thomas Burnett Swann’s novels and most of his short stories. I recently compiled this quick set of brief reviews of a number of his novels.

I recommend most highly two of Swann’s shorter pieces. “Where is the Bird of Fire?” might be his most famous story, from Science Fantasy in 1962. (It was a finalist for the 1963 Hugo for Best Short Fiction.) And “The Manor of Roses” is my favorite of his stories (it was Gardner Dozois’s favorite as well.) It’s from F&SF in 1966, and it was a Hugo finalist as well. Both stories became much inferior novels: Lady of the Bees and The Tournament of Thorns respectively.

In sum, as minor as the Phoenix Award (which is now defunct) seems to be, it appears to have done a good job honoring worthwhile Southern writers of SF and Fantasy, some prominent (such as R. A. Lafferty and, later, Joe Haldeman), and some not as well known who still deserve attention, such as Richard C. Meredith and the 1973 winner, Thomas Burnett Swann.

Previous articles about Swann at Black Gate include:

Adventure in The Old Kingdom: The Minikins of Yam by Tony Den

Vintage Treasures: The Weirwoods by John O’Neill

Vintage Treasures: Wolfwinter by John O’Neill

Rich Horton’s last artcile for us was a Retro Review of the November 1959 issue of Amazing Science Fiction. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s articles here.

Swan isn’t everyone’s cup of mead (he isn’t mine, that’s for sure), but he’s certainly worth trying. He clearly wasn’t just writing these books to make a buck – he was truly using them to express a unique and individual vision. They meant something to him. I consider him an “Oh my God ” writer a lot of the time, but all the same he had courage and originality, and he’s worthy of respect. Even the best of his books would have benefited from more control and discipline, though.

Sigh. Swann is another writer I totally missed during my formative reading years (1976-1987), and now that I’m 54 and swamped with other responsibilities, I usually devote my precious reading time to trying to stay current. I miss being able to dive wholeheartedly into a 50-cent paperback I found on one of my Saturday sojourns to the bookstores in downtown Ottawa. Maybe retirement will enable me to get a little of that sense of discovery back.

Missed Swann’s work altogether. These sound interest. Thanks for the post.

“Maybe retirement will enable me to get a little of that sense of discovery back.” — It’s worked that way for me, John. And I have you and the Black Gate crowd to thank for a substantial portion of that: I’ve discovered more new — and old — stuff here than I have anywhere else, online or in print. I accepted a retirement buyout in February 2016 at the college where I’d taught for 25 years, and I would often tell anyone who asked that my plans for retirement included catching up on a lot of reading. When my wife passed away in September of that year, without getting the chance to spend a single second of my retirement with me, books were the only distraction that kept me from being a complete emotional disaster area. I’ve had to be a little bit more cautious in my buying habits recently, and I’d trade every book I’ve ever owned or read to have my partner back, but I’m grateful now more than ever for my love of reading, and to Black Gate for alerting me to literally hundreds of great reads I may have never known about.

I came to Mr. Swann’s works from 2 directions. First, it was impossible not to find his books in the stacks of used books at stores or library sales. Second, I enjoyed the Bronze Age/Homeric tales written by another academic fantasist, Richard Purtill (The Golden Gryphon Feather, The Stolen Goddess, The Mirror of Helen), which were tagged “Not since Thomas Burnett Swann…” Mr. Swann’s Classical fantasies sit nicely alongside the Purtill novels and the Vergil Magus books of Avram Davidson (The Phoenix and the Mirror, Vergil in Averno, and the posthumous The Scarlet Fig).

I came by Swann by chance, in a book exchange. The art on the cover and blurb impressed me enough to give it a bash, resulting in my Minikins of Yam post. Will be sure to look up The Manor of Roses based on Richs’ recommendation.