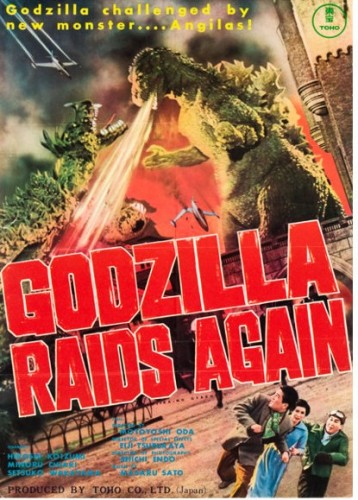

Godzilla Raids Again / Gigantis the Fire Monster (1955)

It was disheartening to sum up the recent Godzilla anime trilogy, the only Japanese Godzilla films I never plan to rewatch. Even with the Hollywood mega-millions epic Godzilla: King of the Monsters only a few months away, the feeling of deflation within my favorite movie franchise made it necessary for me to plug a bit of hope into my schedule immediately. Not by watching a great Godzilla film, mind you, but by watching a mediocre Godzilla film. Why? Because it’s the best way to remember how even lesser entries in the series can offer some enjoyment. Like watching Godzilla actually move. This is a radical concept the anime filmmakers let slip past them.

Thus I present Godzilla Raids Again, a middle-of-the-road G-movie that’s mostly faded into obscurity despite its prime position as the first Godzilla sequel.

To date, Toho Studios has released thirty-two feature-length Godzilla films. In any series with such longevity, a few installments slip off the pop culture radar. But it’s almost never the second movie that suffers this fate. The first sequel to a smash hit, regardless of quality, is a major event. The many films that come after are where the grayness of oblivion sets in.

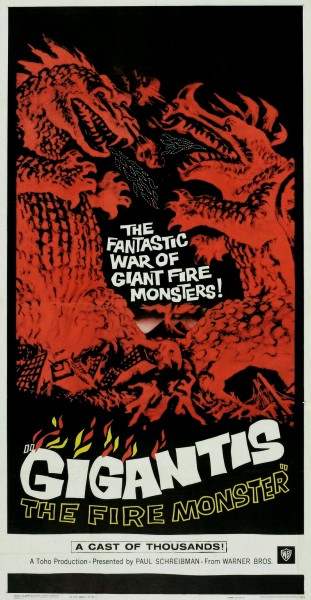

Yet Godzilla Raids Again, released in 1955 only six months after the original, is one of the least seen of the Showa Era Godzilla movies. Many viewers outside Japan are unaware it exists. If they are, they may not know it’s a Godzilla film at all because it was released in the US and much of the rest of the world as Gigantis the Fire Monster. Godzilla’s name not only vanished from the title, it vanished from the dubbing. Not until 2006 did a North American DVD containing both the Japanese and US versions bring the film out with the classic monster’s name reattached. The DVD producers digitally superimposed the title Godzilla Raids Again over the spot where Gigantis the Fire Monster once appeared … although the dubbing with the name “Gigantis” remained.

How Godzilla became Gigantis and then pulled a cultural vanishing act is quite the tale. But let’s first look at the actual Godzilla Raids Again, which is its own strange story and a stopgap moment in the early history of the Japanese giant monster (kaiju) film.

Godzilla Raids Too Quickly and Cheaply

Yes, Godzilla Raids Again premiered in Japan a mere six months after the original. If that sounds like too fast a turnaround, you’re correct. Iwao Mori, head of Toho Studios, told producer Tomoyuki Tanaka to start prepping a sequel after Godzilla had been in theaters for only a week. The Toho brass wanted a quick cash-in on the popularity of Godzilla and didn’t foresee a long-running movie series.

With a rushed schedule, reduced budget, and key creative personnel missing, the film that arrived in theaters half a year later was … not fantastic. To be generous, it’s as good as could be expected given the limitations. The box office receipts matched the film: profitable, but unremarkable. Toho dropped Godzilla until 1962 and turned to other giant monsters and SF films, Rodan and The Mysterians, which were huge hits in 1956 and ‘57.

Few fans have much regard for Gojira no gyakushu (“Godzilla’s Counterattack” or “Godzilla’s Revenge”). The second and last Godzilla film shot in black and white and 1.33 aspect ratio, Godzilla Raids Again doesn’t have much passion. The nuclear metaphor that made the original film so memorable is dampened, and the human story is poorly woven into the monster action and trite on its own merits. When the monsters aren’t on screen, a pall of ordinariness falls over everything.

On the plus side, this is the first Godzilla film to feature the famous monster fighting it out with another giant monster (Anguirus, a quadruped saurian with a horned shell), and some of the special effects sequences from Eiji Tsubaraya and his team are impressive. The VFX department may have had less time to put together their effects, but they already had experience overcoming the difficulties of creating giant monster magic.

The tight production schedule meant a key figure in the success of Godzilla wasn’t available: director Ishiro Honda. Honda brought immense personal vision and earnestness to the first film, but he was already busy directing Love Tide for Toho. The studio had to find a replacement, and they picked journeyman director Motoyoshi Oda. It wasn’t the right pick. Oda had trained in Toho’s director program under some of the greats, including Akira Kurosawa and Senkichi Taniguchi. But Oda’s career was mired almost entirely in programmers. Toho may have chosen him for Godzilla Raids Again because he directed The Invisible Avenger in 1954 and had some experience with special effects. Oda didn’t have Honda’s investment in the material (the rushed script didn’t help) and he handled the direction with the same blandness as if it were any other assignment from his undistinguished filmography.

Also AWOL is Godzilla composer Akira Ifukube. In his place is one of the great composers in Japanese cinema, Masaru Sato. However, Sato was early in his career, and remarked later in life that the score to this film sounded like “a kid trying to learn.” He’d later do great work for the Godzilla series, such as the groove of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla and the tropical fun of Son of Godzilla. But his music here is anonymous and doesn’t bring the bolt of energy or boom of doom the movie desperately needs.

The monster side of the story is easy to summarize and requires almost no reference to the characters in the human storyline. Another Godzilla (played again by stuntman Haruo Nakajima), belonging to the same species as the one that perished in Tokyo Bay, is sighted on an island near Japan. This second Godzilla is battling with another huge prehistoric monster, a spiked carapace creature called Anguirus, which has a phonetic similarity to the Japanese pronunciation of the dinosaur Ankylosaurus. (In some English sources, the monster’s name is spelled Angilas because of the ambiguity of the “R/L” sound in Japanese; the hard “R” sound doesn’t exist as a distinct phoneme in the language.)

Godzilla heads toward Osaka, and the city braces for an attack. The military, after consulting with scientists who feel there’s no hope to halt the monster, uses flares to distract Godzilla away from the populated port city. But three convicts escaping from a paddy wagon (a sequence that seems to phone in from another movie) drive a gas tanker into a petroleum plant, igniting an explosion that lures Godzilla back to shore.

As Godzilla makes landfall, so does Anguirus, and the two monsters commence their titanic tussle while leveling the center of the city — including its beautiful sixteenth-century castle, one of Japan’s great landmarks. (Don’t worry, it got rebuilt in time for ninjas to train there in You Only Live Twice.) Godzilla kills Anguirus with a vicious bite to the neck and then roasts the corpse with a radioactive blast. Satisfied with the victory, Godzilla wades back out to sea, leaving Osaka a smoking ruin—although a much less impressive ruin than the wreckage of Tokyo in Godzilla.

The monster moves toward the northern island of Hokkaido. Japanese Self-Defense Force jets attack the monster on a snow-covered islet with high peaks. Unable to destroy Godzilla directly, they switch tactics to use missiles to trigger an ice avalanche, which eventually buries the monster in a deep freeze, immobilizing it until King Kong vs. Godzilla seven years later.

The main draw of Godzilla Raids Again is the battle between Godzilla and Anguirus — the first confrontation between two monsters in the history of Japanese movies. It’s a thrilling fight that holds up well against many later Godzilla spectaculars. The VFX crew was new at this type of action, but hurled themselves into making the battle as devastating to the models of Osaka as possible.

Anguirus is a wonderfully designed creature that exudes as much personality as Godzilla, a bit like an aggressive but friendly dog. This helped to turn Anguirus into one of the most popular supporting monsters in the series, usually as one of Godzilla’s allies (Godzilla vs. Gigan, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla). Katsumi Tezuka, the stunt performer in the Anguirus costume, had to walk on his knees when Anguirus moved on all fours, but the staging and camerawork hide this, something the 1970s movies would handle far less adeptly.

The fight is choreographed in an animalistic fashion much different from the later anthropomorphized monster battles. Godzilla and Anguirus lunge at each other in a fury of biting and clawing. At some points, the fight snaps into jerky hyper-motion, apparently a mistake by an inexperienced effects cameraman who set his camera at a lower speed. It ends up working surprisingly well as it comes as such a shock when the creatures appear to go fully ballistic tearing at each other

Effects master Eiji Tsubaraya devised ingenious camera angles to film the fight, and the opticals mixing fleeing people with the destruction creates a tangible sense of the monsters’ size. There’s one superb effects shot of the fleeing convicts consumed with water rushing into a train station tunnel that’s almost seamless. The model of Osaka Castle is the most impressive miniature, and the animated shots of it starting to crack before Godzilla smashes Anguirus into it build tension as the fight reaches its climax. The castle demolition must have thrilled Tsubaraya, since he knocks down feudal castles in the next two films, King Kong vs. Godzilla and Mothra vs. Godzilla.

The avalanche attack on Godzilla at the end is almost as impressive effects work, although it doesn’t have the same rush. It’s one of the most creative ways of destroying a giant monster to appear in any film of the genre, and Godzilla composed against the massive ice-crusted cliffs makes for a number of stunning shots. It’s unfortunate the screenplay paces the attack in a way that it breaks in the middle while everyone goes to re-load their planes at the base. The build of the suspense gets hacked down when it’s ready to peak.

The human story is soap opera piffle about the employees of a fishing company in Osaka whose lives intersect in unbelievable ways with the monster affair. Heroes Tsukioka (Hiromi Koizumi) and Kobayashi (Minoru Chiaki) pilot planes to spot schools of fish to guide the company’s trawlers. It makes sense two pilots might find themselves on a distant island with the monsters, but after their discovery they don’t have much else to do. In other movies, the focus would shift to the scientists and military men who have to halt the titanic dangers.

But after a debriefing scene — which contains the only appearance of a character from the first movie, Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) — Kobayashi, Tsukioka, Tsukioka’s girlfriend Hidemi (Setsuko Wakayama), and the other employees at Kaiyo Fishing Industries continue to hang around the movie through contrivance. For example, after the massive wreck in Osaka, the company decides to send the main characters north to Hokkaido — so they just happen to get in the way of Godzilla’s movements. They also have a few good laughs standing in the demolished office in a leveled city, which feels wrong on many levels.

Most of the cast’s interaction is dull. If it sometimes seems somber, that’s probably the fault of the pacing, quiet soundtrack, and gloomy black and white photography. After the shift to Hokkaido, the movie almost grinds to a stop for a ten-minute scene of a dinner party and Kobayashi looking for love. The supposed “sacrifice” of Kobayashi during the final strafing run on Godzilla is supposed to be the emotional capper, but Kobayashi only dies in a foolhardy accident, and that the Japanese Self-Defense Force gets the idea for the avalanche from his crash is also an accident and nothing Kobayashi planned. Tsukioka’s final words to his dead friend after Godzilla’s icy burial is the only moving moment to come out of this character death.

The other moment that stands out among the humdrum soap suds is Hidemi watching the city of Osaka burn from her hilltop house. The matte painting of the flaming city, made to resemble a mushroom cloud, is beautifully unsettling. We can imagine what thoughts are going through Hidemi’s head knowing that her beloved is down among the horrors. It’s a brief moment where Godzilla Raids Again embraces the nuclear metaphor that made the first film so powerful. It needs more of this and fewer jokes about matchmaking.

However, it’s always a pleasure to see one of Toho’s great science-fiction faces pop up: Yoshio Tsuchiya, also a favorite of director Akira Kurosawa, appears as a member of the Self-Defense Force who pilots the final attack on Godzilla. Tsuchiya appeared in several Godzilla films, most notably as the Controller of Planet X in Invasion of Astro Monster, a.k.a. Monster Zero (1965), and as the saurian-worshiping World War II veteran in Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991).

The Volcano Monsters and The Fire Monster: The US Version

What happened that caused Godzilla to be changed into Gigantis in North America and then end up in obscurity? Buckle in, this is a lengthy one.

The same group of US financiers who purchased the rights to the original Godzilla also bought the rights to the sequel. Two of the financiers, Harry Rybnick and Edward Barison, made a deal with a fledgling production company, AB-PT, to re-craft the movie using only the special effects footage and shooting a new story around it with English-speaking actors. Danish author Ib Melchior, who later directed Angry Red Planet, and his roommate Edwin Watson created a screenplay called The Volcano Monsters to use the Japanese effects footage. Toho even sent an Anguirus and Godzilla costume to Hollywood so the crew could shoot a few new effects to stitch together the story. As an example of how this new movie was going to bend itself in order to squeeze the Japanese footage into a supposedly stateside monster movie, a radio announcer mentions the monsters are fighting in the “Oriental Section” of San Francisco. That totally explains the giant Shogun-era castle sitting in the middle of a Californian city!

As clumsy, inane, and borderline insulting as all this is, The Volcano Monsters did come close to starting production. But then AB-PT’s backers pulled out of the project. After releasing only two films, the company was shuttered and The Volcano Monsters passed into limbo. Considering the similar butchering the Japanese giant monster film Varan (1958) underwent to become the English-language Varan the Unwatchable — uhm, The Unbelievable — nobody mourns the loss of The Volcano Monsters.

Godzilla Raids Again went back on the market. Paul Schreibman, Edmund Goldman, and Newton P. Jacobs purchased the rights in 1958. They made a deal with Warner Bros. for distribution in a package with the classic Mystery Science Theater 3000 movie Teenagers From Outer Space. The new owners didn’t attempt a re-haul in the manner of The Volcano Monsters. Schreibman settled for a cost-effective (i.e. cheap) route, but one that still radically altered the film — starting with stealing the star monster’s name.

The big question: Why did Paul Schreibman rename and redub the film to erase Godzilla and replace it with the uninteresting Gigantis? Schreibman’s original answer was that he didn’t want the film to be confused with a re-release of Godzilla, King of the Monsters! That makes no sense; why would a producer looking for a fast buck not want people to connect his new movie to one of the most successful monster movies ever made?

It appears Schreibman simply made a miscalculation of the marquee appeal of Godzilla and thought he could pass this off as a “new” monster. It was a mistake and a clumsy one, which he later admitted. The few viewers who got out to see Gigantis the Fire Monster in theaters weren’t fooled by the ruse and were annoyed instead. “It’s clearly Godzilla! Why are people calling it ‘Gigantis’?”

The film was dubbed at Ryder Sound Services with a script overseen by Hugo Grimaldi. Grimaldi, not a native English-speaker, filled the dubbing script with unintentionally hilarious tin-eared dialogue, such as the infamous “Banana oil!” line, a bit of slang that was out of date when the Volstead Act was repealed. One of the scientists, while attempting to explain the existence of Anguirus, claims to have gotten his information from a new book called Anguirosaurus, Killer of the Living. Grimaldi also crammed the script with nonstop voiceovers from Kobayashi (voiced by Keye Luke) that are literally a play-by-play of what’s on screen. (“I picked up my microphone.” “I started to wave.”) Grimaldi may have gotten the idea for the voiceover narration from the King Brothers’ version of Rodan, which reached the US a year before Gigantis.

Most of Masaru Sato’s music was replaced with wall-to-wall library music meant to make the film seem more urgent, but it quickly turns irritating. Schreibman also heaped a load of stock footage into the movie to boost the action, which of course means it opens with a lengthy montage of rocket launches while a voice-of-doom narrator (Marvin Miller, who played this part a lot) explains the dangers of nuclear testing, blah, blah, blah. The re-editing of the sound effects creates a funny error, where Anguirus’s roar is dubbed over Godzilla’s, even further robbing the monster of its identity.

The result is a ludicrously funny B-picture, and it leaves no doubt why people ignored the film on its original 1959 release. Although altered less than Godzilla when it was Americanized as Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, Gigantis the Fire Monster retains far less of the spirit of its original. But it does merit watching for weird amusement. Several famous voice-over artists lent their talents, including George Takei and the ubiquitous Paul Frees. But all turn in hammy, cartoon performances, probably at Grimaldi’s insistence, and the delivery of the already bizarre lines amps up the camp value.

Especially entertaining is the film that Dr. Yamane shows to the council of generals and scientists to explain Godzilla’s threat. In the Japanese version, the footage is from Godzilla’s rampage in the first movie, played silent except for the eerie sound of the projector. It fits with the gloomier tone of the film, and even if it isn’t that exciting (thanks, I’ve seen Godzilla), it makes an impression. The version of this scene in Gigantis the Fire Monster contains constant music, redundant explanations from the actor voicing Yamane, and best/worst of all, additional footage lifted from children’s educational strips explaining the loopiest theory of the development of the Earth ever foisted onto a ‘50s SF flick.

The Fire Monster Today

I enjoy Godzilla Raids Again more than I once did. I never saw the US version on television when I was a kid — it was almost a lost film after the early ‘60s because its owners never tried to sell it to TV. My first viewing was of the Japanese film on an imported VHS tape. It didn’t hold my interest, feeling like a poor version of the original movie and too drab to watch regularly. These feelings are widespread among Godzilla fans.

Seeing it a few more times on superior quality DVD and comparing it to the craziness of Gigantis the Fire Monster has given me a greater appreciation for what does work: the special effects. Once I maneuvered around the bland state of the rest of the movie, I can thrill to the big set pieces of Godzilla vs. Anguirus and the avalanche assault, both of which have some jaw-dropping visuals. The US hack-job can’t mess this up, even with the unnecessary music and Godzilla forced to borrow Anguirus’s roar.

My greater fan appreciation still can’t make me think Godzilla Raids Again is anything but the weakest of the first six Godzilla films. Appropriately, it’s the only of the six without director Ishiro Honda. On one side of it is the bleak masterpiece of Godzilla, and on the other are the colorful thrills of the full-blooded Japanese science-fiction phenomenon. The Fire Monster is the poor middle child.

Godzilla Raids Again is one of several Toho SF pictures whose North American rights the Criterion Collection currently owns. They have yet to release any on DVD or Blu-ray, but they’re currently streaming them on Starz. Although Criterion has stated they have plans to release their library of kaiju films (which includes Rodan, Mothra vs. Godzilla, Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster, and War of the Gargantuas) on physical media, no official announcement has come in over a year. Come on, Criterion, step it up! At least these films have been liberated from Classic Media’s stingy grip.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

Is Anguirus the only quadruped in their stable?

There’s also Baragon.