Artzybasheff’s Robots

Boris Artzybasheff is one of my favorite science fiction artists. He’s one of my favorite artists, period, but I put it that way because most people never think of him as a science fiction artist. Look at his work through that modifier, though, and it snaps into place. Perhaps no other artist sees the alien in the everyday as much or depicts it as well as Artzybasheff.

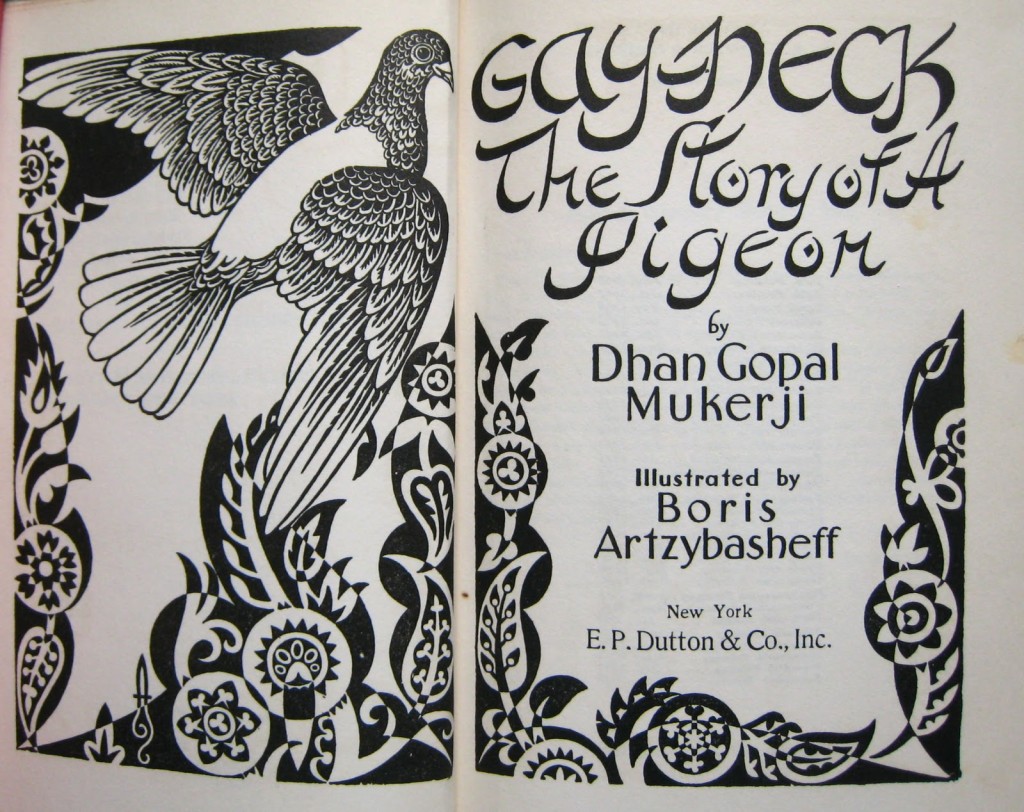

Born in Russia in 1899, he fled to New York in 1919 after having fought with the White Russians. He didn’t speak a word of English. Nevertheless he was a working illustrator by 1922 and supplied the art for the Newbery Award winning Gay-Neck, written by Dhan Gopal Mukerji in 1928.

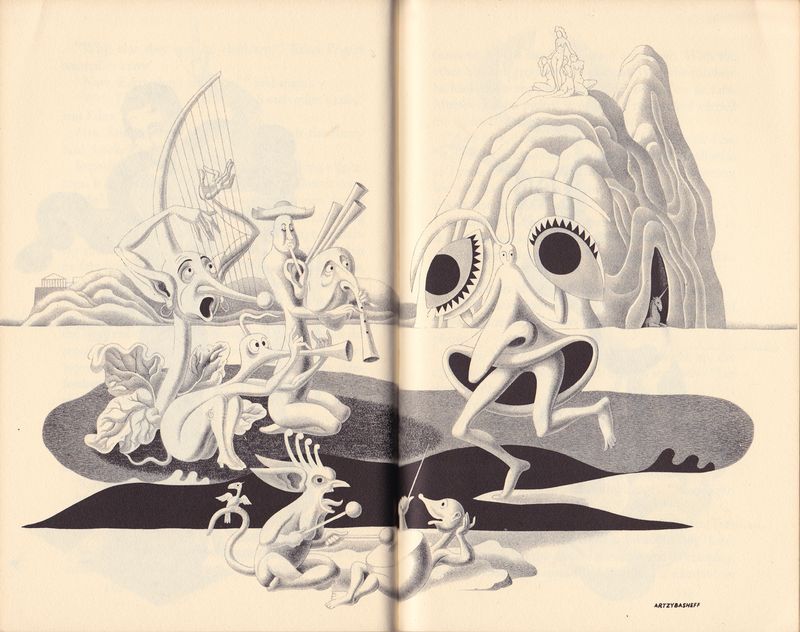

That early art was stylized but mundane, in the f&sf usage of the word. Nevertheless, publishers saw his true strengths from the beginning. Few mainstream presses released fantasy before WWII but those who did made Artzybasheff their go-to artist. He did the covers for classics like The Worm Ouroboros, The Incomplete Enchanter, and Land of Unreason.

And, most famously and most influentially, both the cover and interior art for Jack Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao (1935).

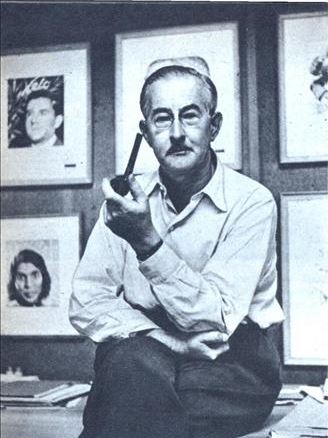

Would there be a Hannes Bok if not for Boris Artzybasheff (pictured in his office in 1954)?

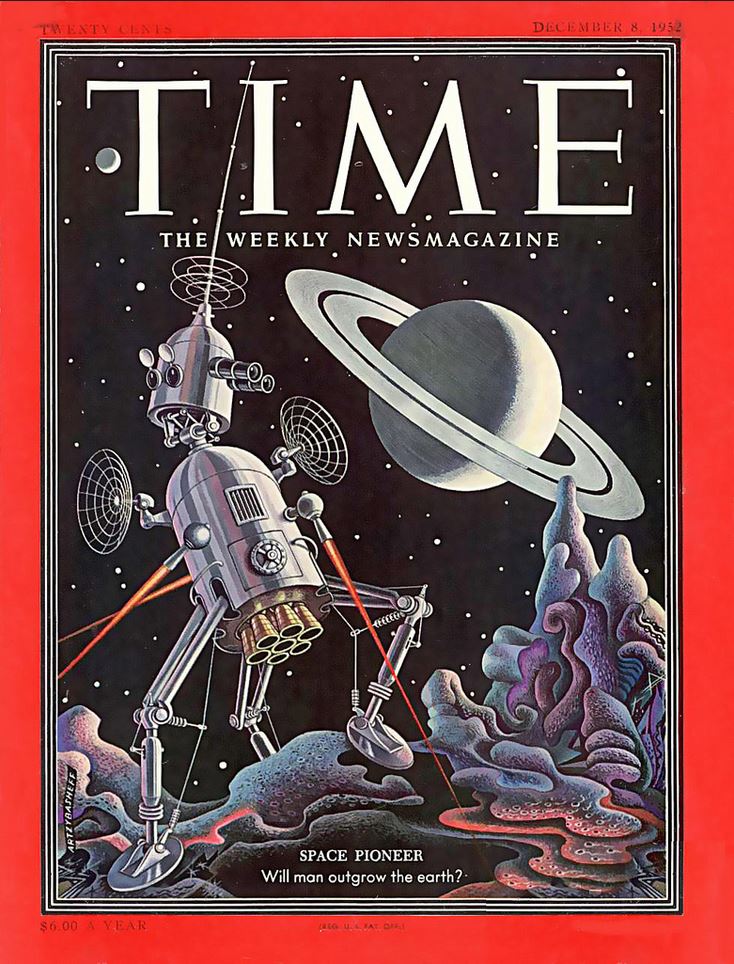

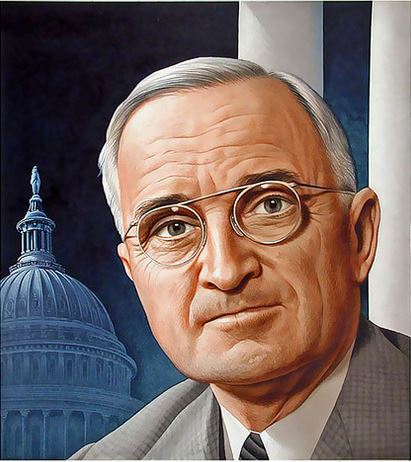

By the early 1940s, he was one of the most in-demand artists in America. Henry Luce scooped him up to do covers and art for Time and Fortune. His ability to switch between the fantastic and realistic was legendary. His portraits of newsmakers during the war defined Time’s look, making its covers pop out on newsstands.

|

|

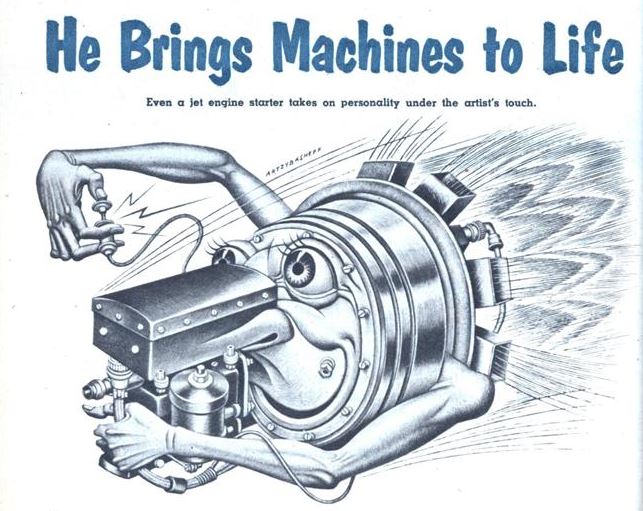

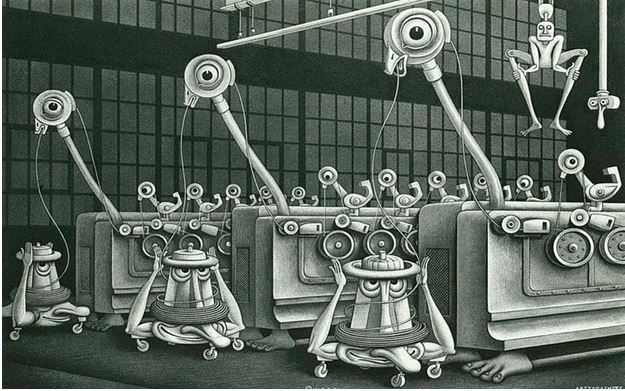

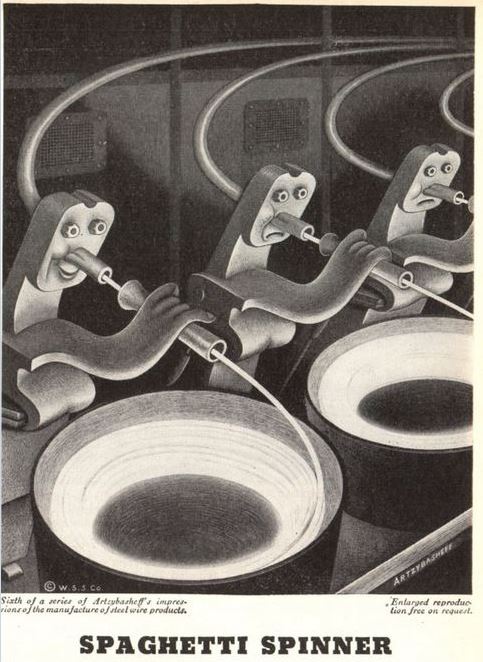

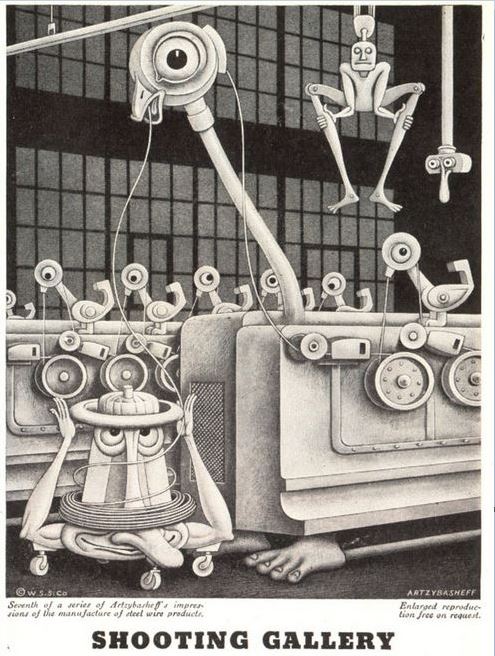

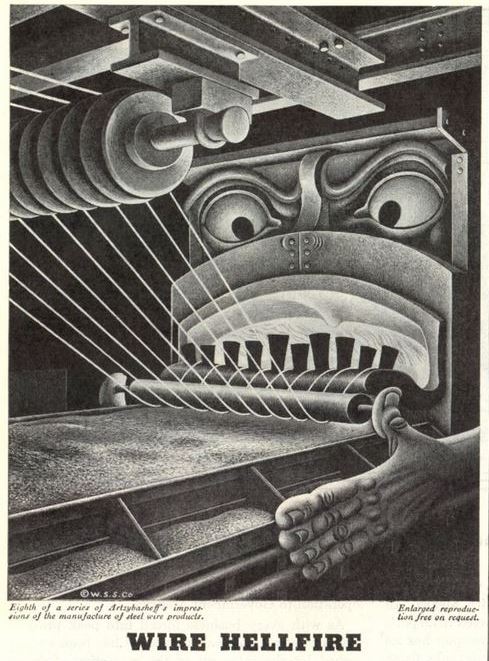

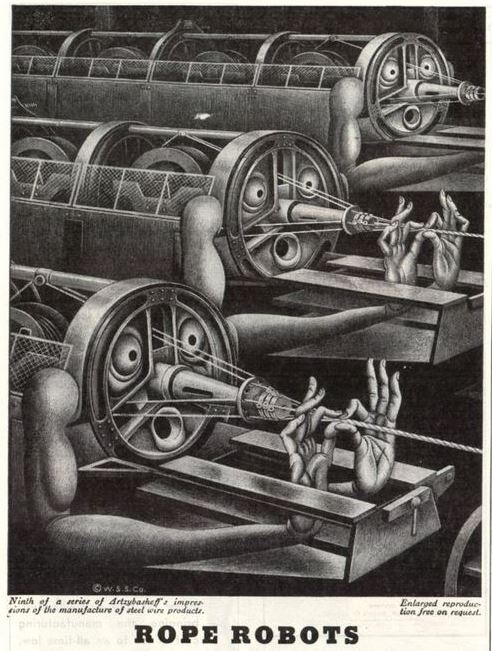

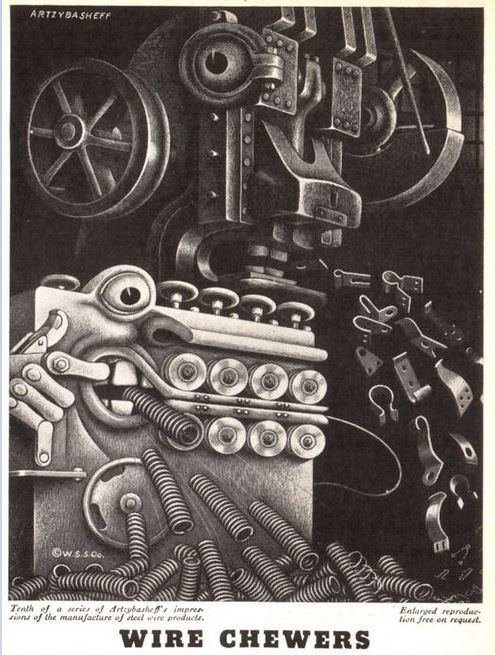

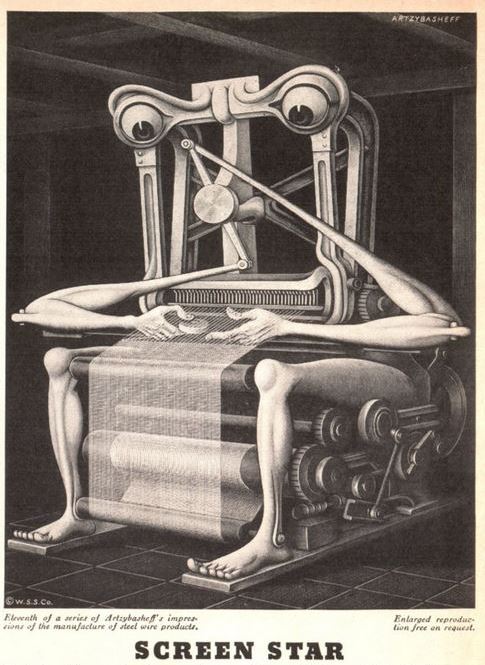

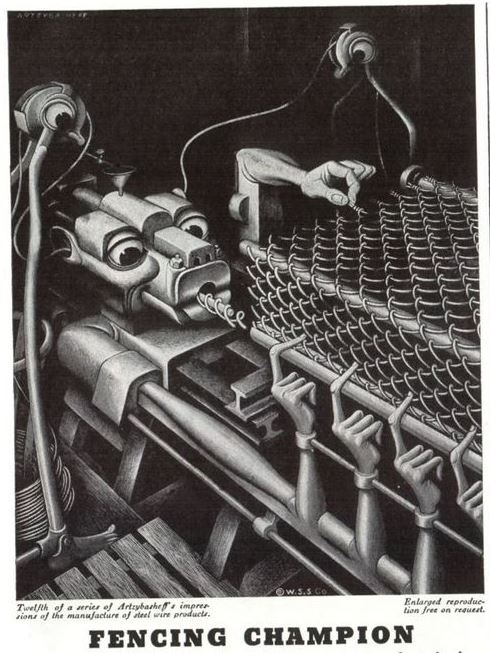

Yet it was his uncanny anthropomorphized machines, what he called “machinalia,” that drew the big bucks.

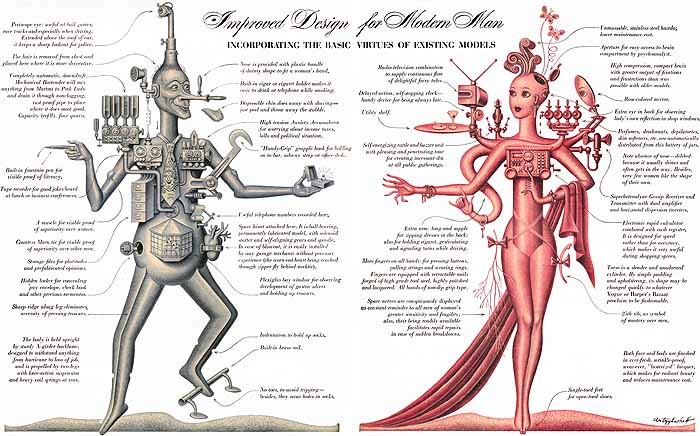

(Parenthetically, he also mechanized people, as in his Improved Design for Modern Man, one of my favorites. That, along with machinalia and much more is in his classic book As I See, now a collector’s item, even in reprint.)

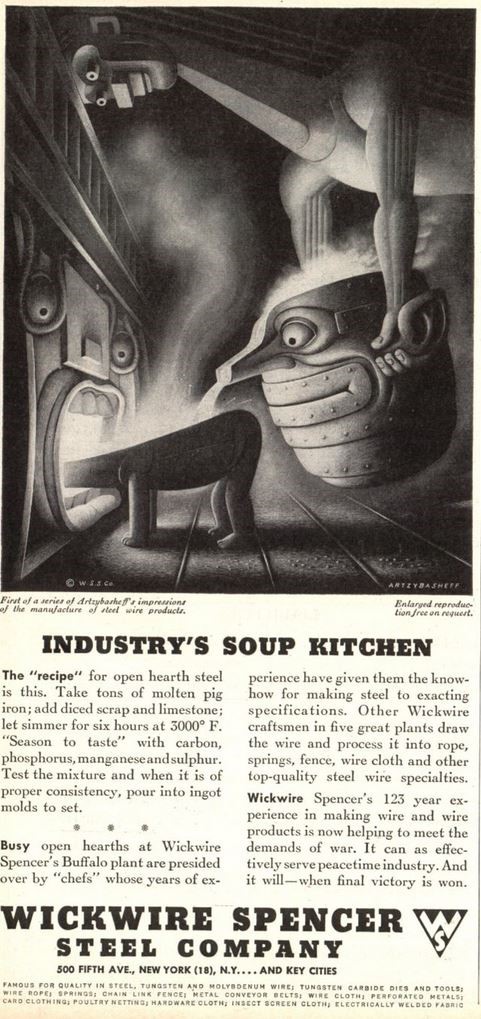

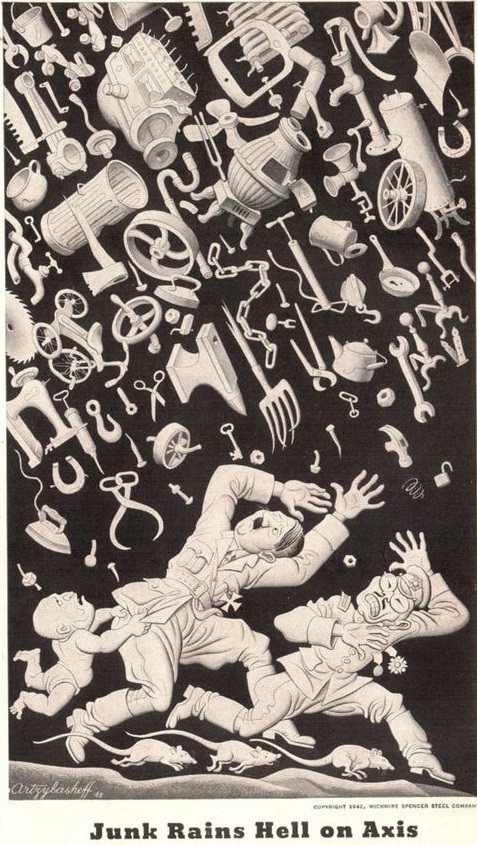

An Artzybasheff machine in an ad hooked eyeballs as efficiently as his portraits; companies whose names weren’t exactly household words camped on his doorstep waving banners of hundred-dollar bills. One such firm was Wickwire Spencer Steel. So minor that it doesn’t rate a Wikipedia entry, Wickwire was one of the many industrial plants thriving in and around Buffalo when the city was at its peak as a broad-shouldered steel and chemical powerhouse. Temporarily flush with government contracts, Wickwire undoubtedly remembered its near-extinction when it went through receivership and looked worriedly at the future after the war when furious competition would roil the industry.

Some clever mind had a cunning plan. Hire Artzybasheff for a series of ads anthropomorphizing the steel-making process. And – the and was crucial – give away the stunning pieces of art for free just by asking for it. Imagine it. Even “unforgettable” ad campaigns fade from memory. Works of art linger on walls for years, sometimes decades. Not to mention the magical appearance of a list of names, thousands, tens of thousands, the most valuable property in promotion, of people who have already expressed interest and can be approached again from a base of familiarity.

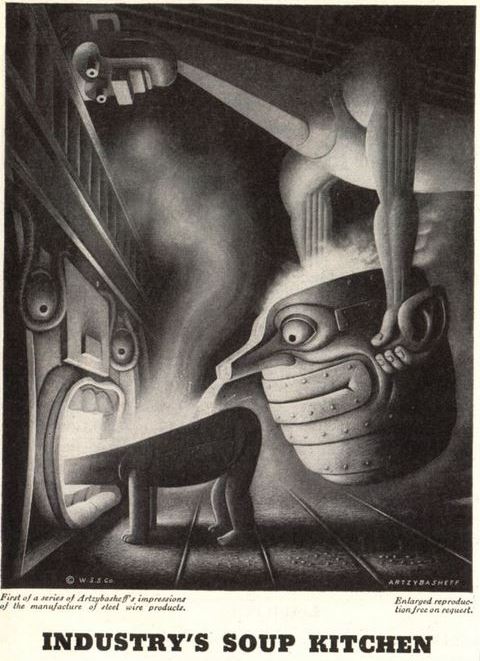

Wickwire bought two columns of ad space in 12 issues, a way to get a steep discount on pricing. Every four weeks, starting on January 15, 1943, readers flipping through pages stumbled over art that looked like absolutely nothing else in that era.

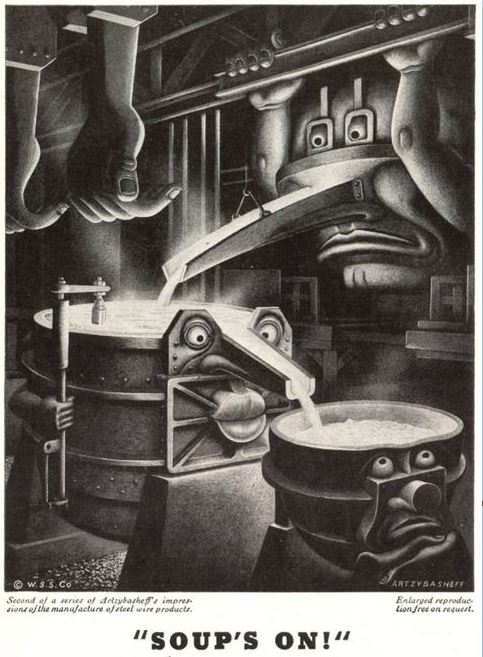

Hieronymous Bosch would be proud. Even the furnace is anthropomorphized with a face, with teeth. Not sure about the bear-lookalike who’s getting molten steel poured down its back, though.

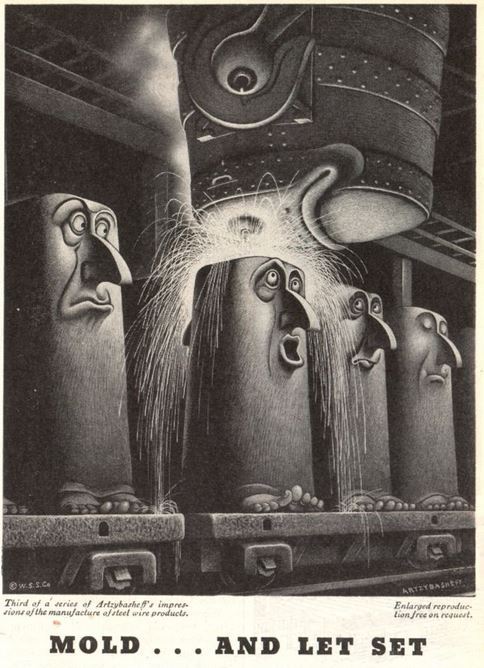

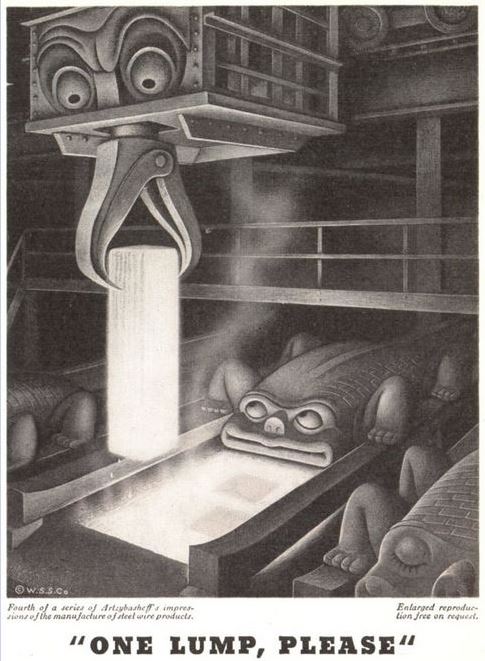

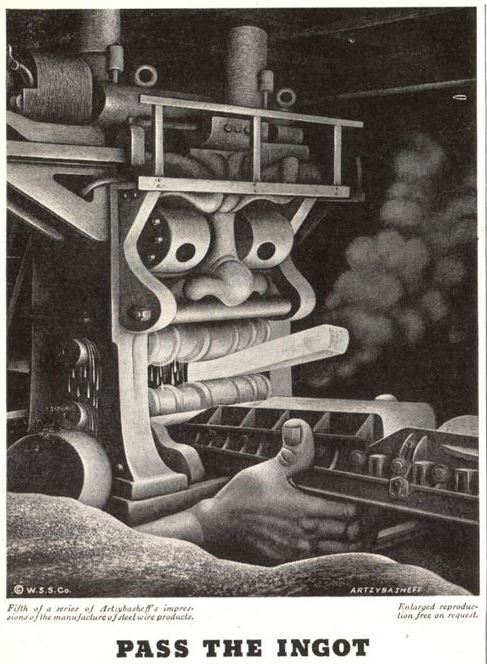

Here’s the full series of 12 images, with the boring ad copy trimmed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

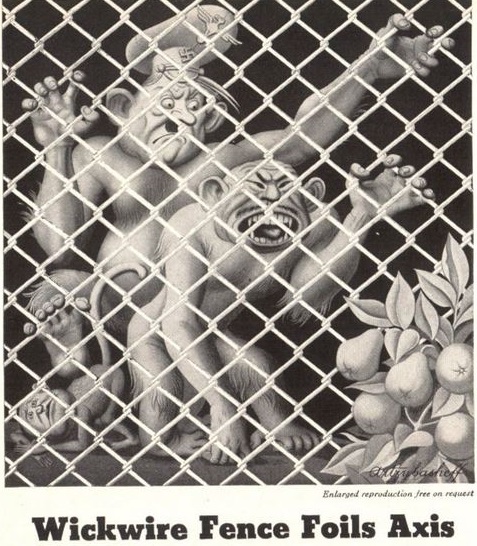

The twelfth ad is somewhat of an anticlimax. Wickwire did not make tanks or boats or any of the other heavily armored weighty steel products that provide shock and awe to war movies. They made chain-link fences. Most people at the time didn’t order chain-link fencing by the name of the manufacturer. They wandered down to the hardware store and bought whatever was on hand. The logic behind the expensive campaigns by companies that were nameless then and remained so after the war escapes me.

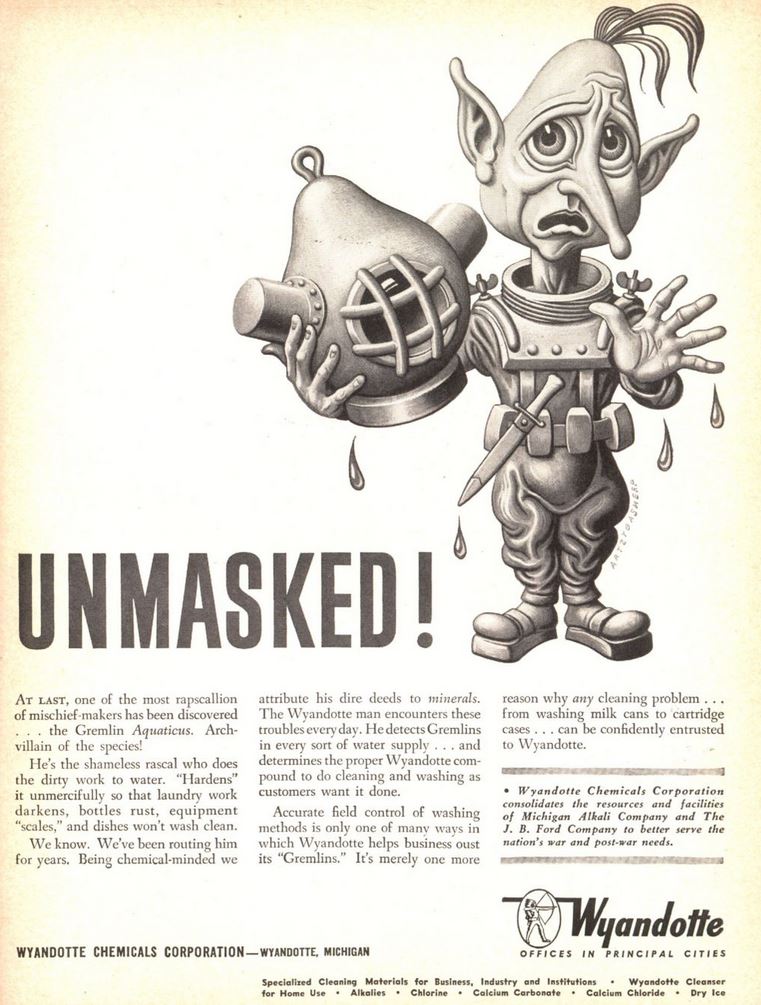

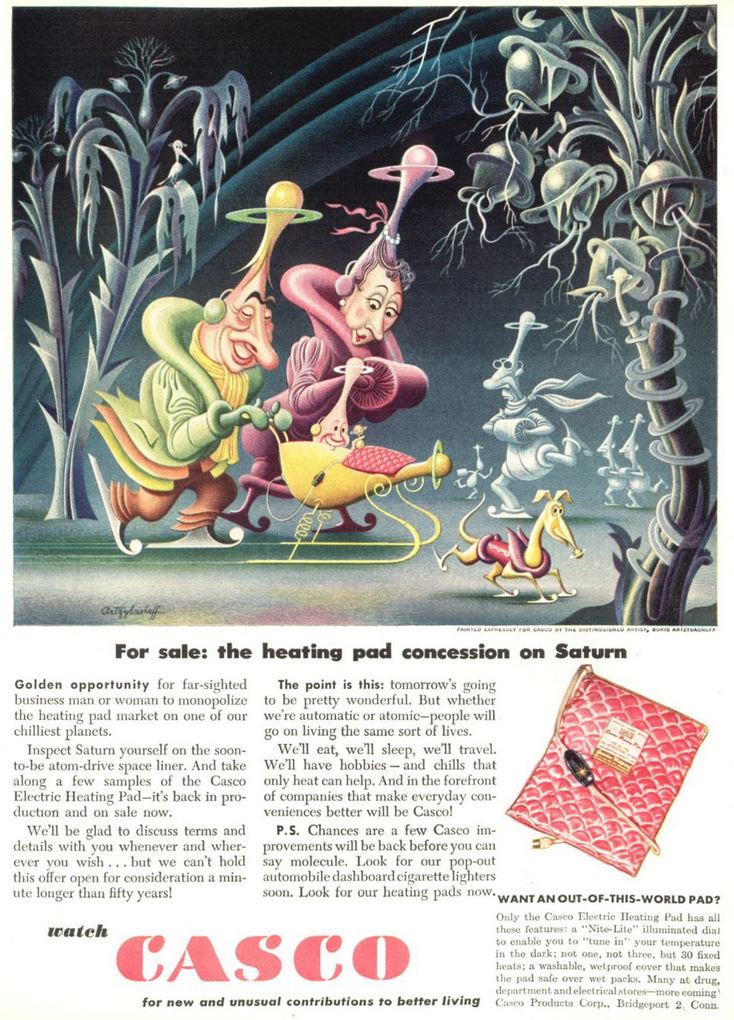

Yet flipping through those pages of Time and other magazines provides countless examples of small companies with huge ad campaigns, some of them also hiring Artzybasheff to work his magic. I can’t keep myself from sharing. Here are three – yes, three! – bonus Artzybasheff campaigns.

First, a wonderful alien gremlin, the Spaniard in the works per John Lennon, brought to you by Wyandotte Chemicals Corporation.

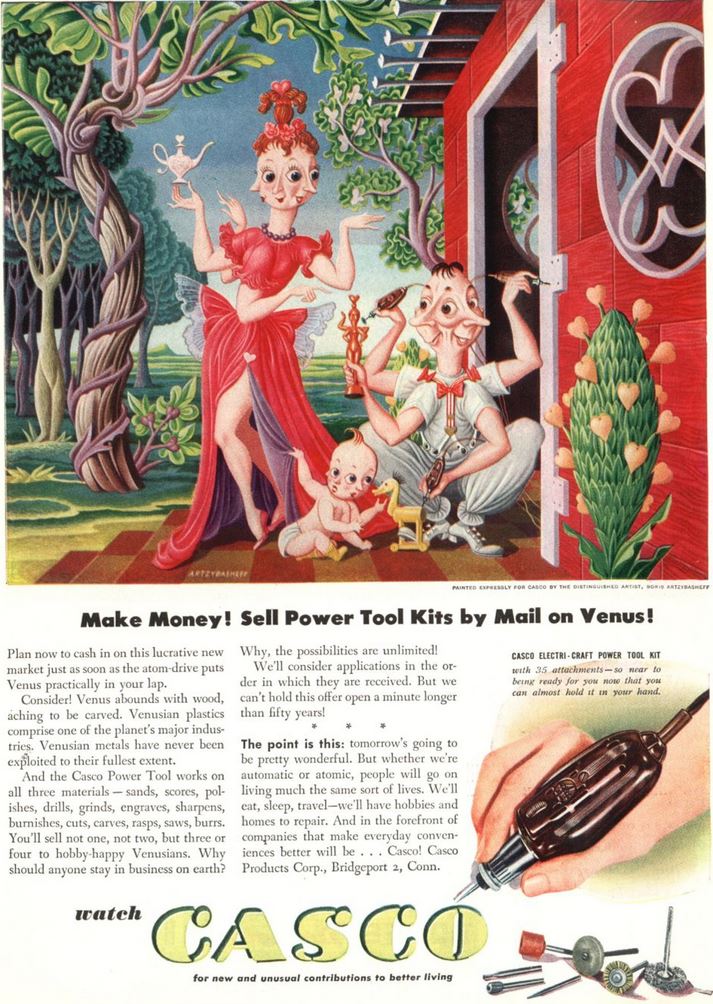

Another company whose products you couldn’t name without a cheat sheet was Casco Products Corp. of Bridgeport, CT, who at the end of 1945 and early 1946 spent untold thousands of hard-earned dollars to buy three full-color ads in Time to hawk their … Electric Heating Pads, “Pop-Out” Auto Dashboard Cigarette Lighters, and Power Tools. Bizarre and certainly unreplicated. Far more alien than anything portrayed by the dull-minded artists in contemporary science fiction magazines, who should have been the audience being far more deserving of them than the white-collar snobs who read Time at the time.

|

|

|

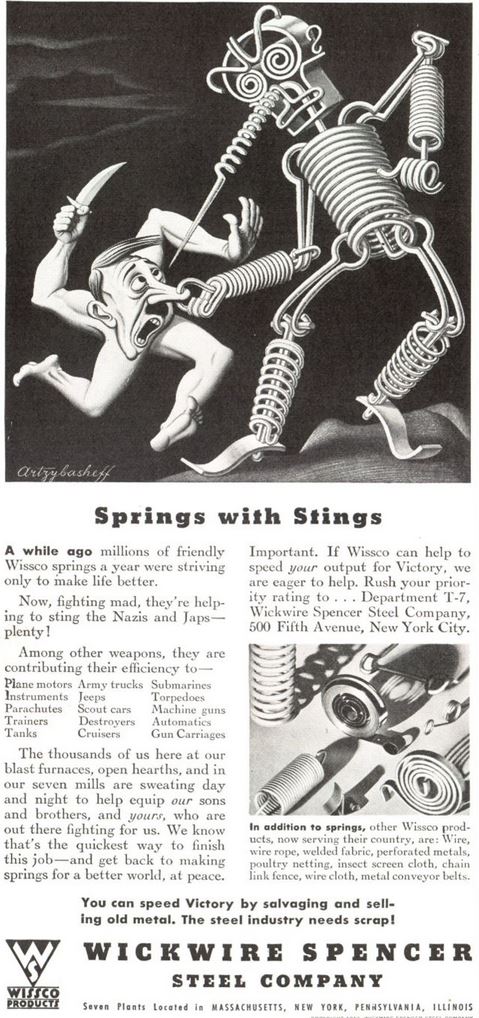

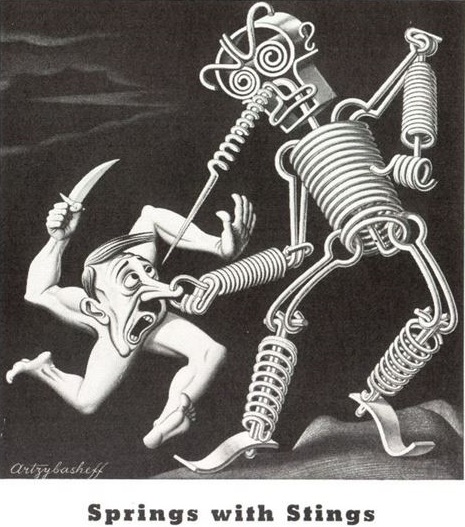

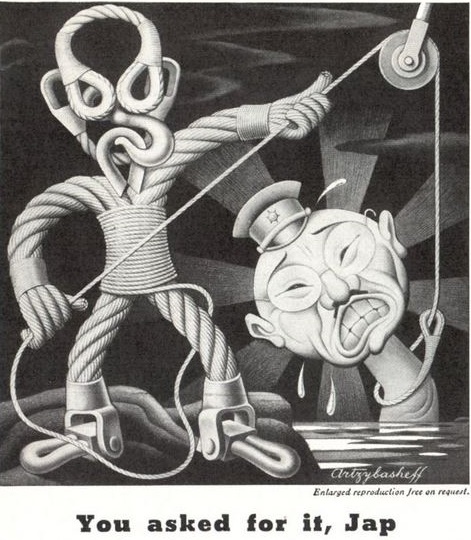

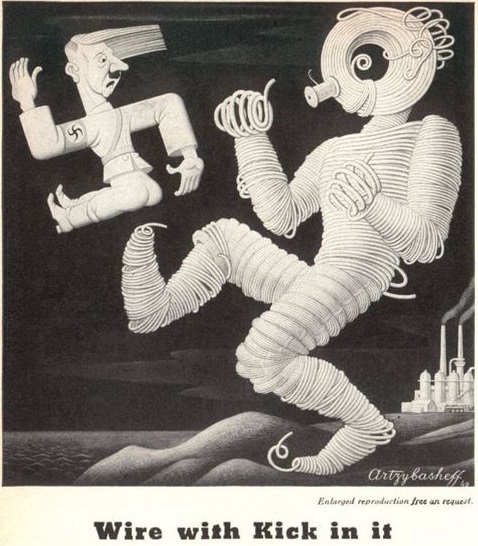

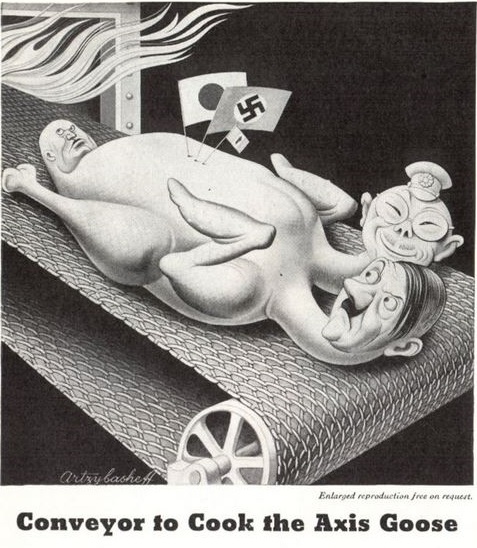

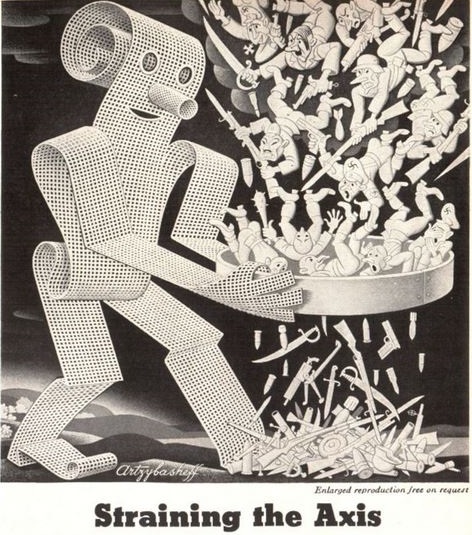

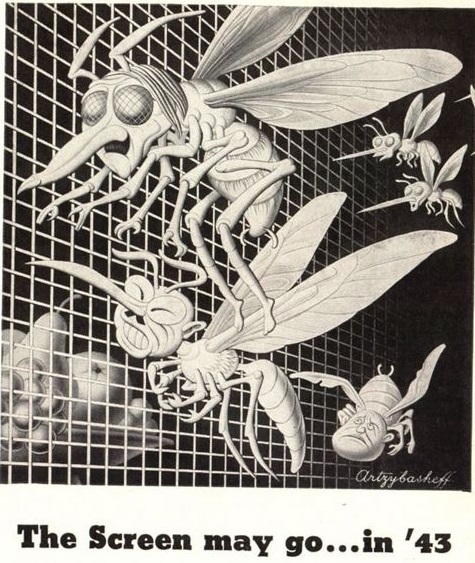

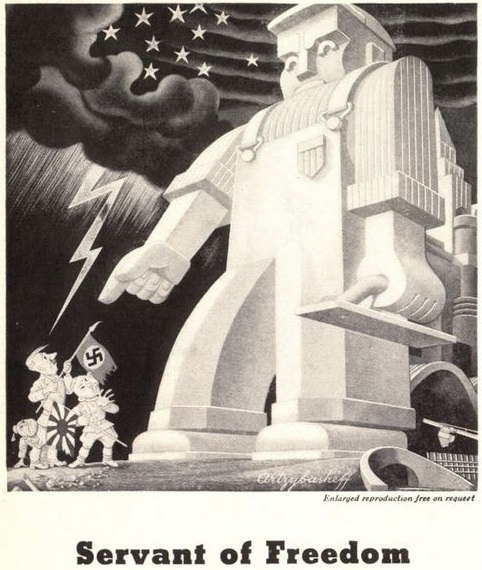

And now bonus number three, the earlier and far less famous campaign Artzybasheff drew for Wickwire in 1942 and 1943. The country was still in the infancy of the war, when kicking Hitler and Tojo personally in the teeth appealed to old and young. Artzybasheff’s machine men did that job as efficiently as Captain America, testifying to the unmatchable strength of chain-link fences. Or something. Don’t think too hard about it. The first ad appeared in the June 29, 1942 Time, before any of the deliberately futuristic campaigns started. The ad industry was still feeling out what was and wasn’t acceptable. Anger sold better than whimsy, but sheer anger is hard to sustain. As the war wore on and on, lightness crept back into advertising, acknowledging the humor with which Americans met the sheer insanity of their new lives. “Springs with Stings” caught that developing mood perfectly. If not true robots, these machinalia are their closest possible cousins.

Here’s the entire series, again with ad copy cropped.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dozens of sites online have examples of Artzybasheff’s art, some of it you’ll surely recognize without realizing that it’s one of his. He never stopped drawing his anthropomorphic machines and mechanized people and his robots dazzled millions. He died too young in 1965, working almost to the end. He is missed.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was A Smattering of Sexbots.