Rescued from the Vaults of Time: The Sapphire Goddess – The Fantasies of Nictzin Dyalhis

Dave Ritzlin, impresario of DMR Books, has rescued another writer from the distant, fog-obscured days of pulp fantasy. He has done for Nictzin Dyalhis as he did for the nearly-forgotten Clifford Ball (reviewed by me here). If you, like most people, have no idea who Dyalhis was, Ritzlin presents as much information as is available in an excellent introduction to The Sapphire Goddess (2018), his new collection of all nine of the author’s fantasy and science fiction stories.

Dave Ritzlin, impresario of DMR Books, has rescued another writer from the distant, fog-obscured days of pulp fantasy. He has done for Nictzin Dyalhis as he did for the nearly-forgotten Clifford Ball (reviewed by me here). If you, like most people, have no idea who Dyalhis was, Ritzlin presents as much information as is available in an excellent introduction to The Sapphire Goddess (2018), his new collection of all nine of the author’s fantasy and science fiction stories.

A quote from the introduction:

Even though Nictzin Dyalhis was the eccentric author’s legal name at that time, it’s highly unlikely he was named that way at birth. He claimed that “Nictzin” was a Toltec Indian name and “Dyalhis” was an old English (or, alternately, Welsh) surname. Neither of these claims is true. Many speculated that his real name was Nicholas Douglas or Nicholas Dallas or something similar, which he modified into something more exotic.

Nonetheless, Weird Tales publisher Farnsworth Wright swore to Donald Wandrei that all the checks for Dyalhis’s stories “were made out to that name.” Whatever the reality, there’s something wonderfully perfect about a fantasist being remembered solely by a name of mysterious origins.

The nine stories in The Sapphire Goddess were published between 1925 and 1940. Eight were published in Weird Tales, with only “He Refused to Stay Dead” published in another magazine, Ghost Stories. Save for the explicitly sci-fi “When the Green Star Waned” and its sequel “The Oath of Hul Jok”, they are a mix of horror and heroic fantasy. Running through most of them is a theme of reincarnation or forgotten past lived in another dimension.

“When the Green Star Waned” (1925) and “The Oath of Hul Jok” (1928) are two adventures of the planet Venhez’s greatest heroes. The first concerns a journey to the now-silent planet Aerth to determine why no one’s heard anything from its inhabitants in years. Dyalhis’s first published story, it’s not an especially finely-wrought story, but it is very successful at creating a nightmare atmosphere, made all the more malevolent with horrible semi-material monsters from the dark side of the moon. It also seems to have introduced the word Blastor for ray guns. That alone is a more than worthy legacy for any pulp story.

Of a sudden the Things standing behind the Aerthons ceased flickering, became fixed as to forms, although the change was anything but improvement. For, although they became in shape like other living, sentient, intelligent beings, their faces bore all evil writ largely upon them.

Acquaint yourself with all the depravity, debauchery, foul indecency ever known throughout the universe since the most ancient, forgotten times, multiply it even to Nth powers, limitless, and then you have not approximated their expressions!

Personally, even beholding such aspects made me feel as if, for eons uncountable, I had wallowed in vilest filth! And it affected the others the same way, and we knew, by our own experience, what had befallen the Aerthons.

Readers loved this story, and voted it their favorite of the issue in which it was published. From 1925 until 1940, Weird Tales readers consistently ranked it among the best of all time. The sequel is less spectacular, but still, Dyahlis provides some crazy and awesome scenes. There’s dreamlike intensity to early sci-fi and fantasy from which modern writers might do well to draw inspiration. I’ve harped on this before, but I think it bears repeating; before everything was straitjacketed into distinct genres, no one thought anything of mixing science, the supernatural, horror, and whatever else caught their fancy into all sorts of mad sagas.

“The Eternal Conflict” (1925) recounts a businessman’s excursion to the halls of Lucifer himself. Even more than “Green Star,” reading it is like peering into another’s darkest nightmare.

Reincarnation makes its first appearance in “He Refused to Stay Dead” (1927). Eric Marston, an empirically-minded British WWI veteran, brings his young bride Edwina home to his family estate, Falconwold. Soon she’s acting differently and old Marston family legends start coming to life.

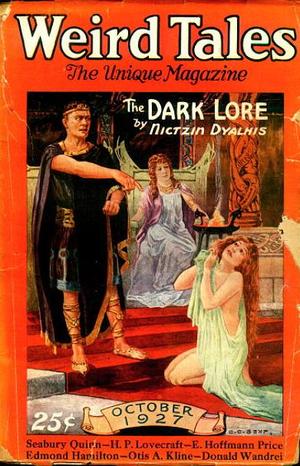

In “The Dark Lore” (1927) an “occultist of some thirty years’ standing” retells “the terrible story” told to him by a woman named Lura Veyle. In a fit of jealousy she dedicated herself to learning the magical (and evil) Dark Lore and killed her sister and brother-in-law. In search of the latter’s spirit, she ends up in a dimension of demons, enslavement, and all manners of physical and psychic torture. It’s almost too long, with definitely a little too much sadistic glee in describing Lura’s predicament. The end, fortunately, replete with restoration and proclamations of an impending new age, is a welcome and satisfying relief after so much horror.

In “The Dark Lore” (1927) an “occultist of some thirty years’ standing” retells “the terrible story” told to him by a woman named Lura Veyle. In a fit of jealousy she dedicated herself to learning the magical (and evil) Dark Lore and killed her sister and brother-in-law. In search of the latter’s spirit, she ends up in a dimension of demons, enslavement, and all manners of physical and psychic torture. It’s almost too long, with definitely a little too much sadistic glee in describing Lura’s predicament. The end, fortunately, replete with restoration and proclamations of an impending new age, is a welcome and satisfying relief after so much horror.

“The Red Witch” (1932) is another story of reincarnation and trans-dimensional travel. This one involved anthropophagous cavemen and ancient witchcraft, both of which should be expected to win me over. Sadly, they weren’t quite enough to buoy me up and I found my mind wandering far more than it should. It’s not a bad story, just one that needed a little paring down.

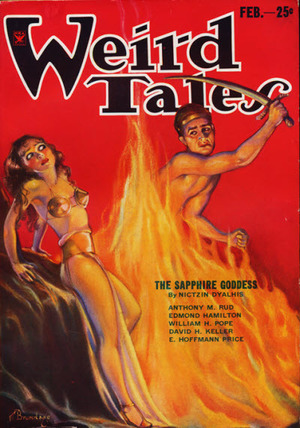

The title story, “The Sapphire Goddess (1934)”, is my favorite in this volume. Presaging Roger Zelazny’s Amber stories, a man of Earth learns he is really King Karan of Octolan, a realm in an extra-terrestrial dimension. He was stripped of his memories and reincarnated in the body of a Earth infant by the evil sorcerer, Djl Grm. Fiery elementals, a seductive princess of Hell, duplicitous wizards, and place names like the Sea of the Dead and the Mountains of Horror help make this straightforward (by Dyahlis standards) story the most brilliantly pulpy in the collection. Between King Karan and his two henchmen, Zarf and Koto, there’s actually a real sense of characterization and even some humor. It’s obvious Dyalhis was improving at wrangling his crazy visions and writing better stories.

During a storm, Heldra Helstrom walks out of wave and into the life of a solitary man in “The Sea-Witch” (1937). Again, past lives play a significant part in this story of Nordic vengeance. It feels like a cold wind from Valhalla that blows all the way back to the lost days of Byzantium.

The final story, “Heart of Atlantan” (1940) is the only one that was really disappointing. It opens with a seance and soon enough there’s automatic writing and an ancient spirit revealing the awful last days of Atlantan, aka Atlantis. It’s a decent enough story, but even with a heart-ripped-still-beating-from-someone’s-chest scene, it’s lacking in the crazed intensity of the previous stories. It’s as if Dyahlis’s improved writing came at the cost of his fiery inspiration.

Nictzin Dyahlis was not a great writer. There are reasons he isn’t as remembered as well as others of his era. His writing can be clunky, and far too often things are “too terrible” and “best unrelated”. The latter device gets really annoying; a couple of times I almost shouted out loud, “Just describe the damn thing, already!” He relied on the same motifs — reincarnation, past lives — too frequently, though I doubt he ever expected anyone to read all his stories back to back.

Nictzin Dyahlis was not a great writer. There are reasons he isn’t as remembered as well as others of his era. His writing can be clunky, and far too often things are “too terrible” and “best unrelated”. The latter device gets really annoying; a couple of times I almost shouted out loud, “Just describe the damn thing, already!” He relied on the same motifs — reincarnation, past lives — too frequently, though I doubt he ever expected anyone to read all his stories back to back.

He was, however, a good storyteller. His tales are fantastically compelling in their absolute over-the-top imagery and narratives. He knew how to grab a reader’s attention and then hold on to it until he reached the end. Here’s the opening of “The Sapphire Goddess” to show you what I mean:

Suicide as a means of escaping trouble never appealed to me. I had studied the occult, and knew what consequences that course involved, afterward.

But I was fed up on life. I was destitute, and had no friends who might help, even were I to appeal to them. At forty-eight, one does not easily regain solvency. And, gradually, I’d lost all ambition. Not even hope remained.

If only there were some other road out — a door, for example, into the hypothetical region of four dimensions… it certainly couldn’t be worse there than what I’d borne in the last three years. Well, I could try…

Dyahalis did more than try, and for the most he succeeded. Anyone with a taste for pulp should give this book a look, and everyone should give Dave Ritzlin thanks for helping preserve and promote another author from the early days of fantasy. Thank you, Dave!

Fletcher Vredenburgh is generally on hiatus here at Black Gate, but will stop by occasionally. He’ll still be posting at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about all sorts of different things.

I’m going to have to get this.

@Charles – It’s more than worth snagging a copy

Done

Ritzlin will be rescuing Wellman’s Kardios tales from undeserved obscurity this year. The man’s on a roll.