Gismo the Great

Would be Tom Swifts in the 1950s had a huge advantage that earlier generations of teens lacked. They had junk. Piles of it. After two decades of needing to keep every piece of machinery and electronics running because parts and replacements were impossible to come by or too expensive to buy, the booming post-war economy finally allowed families to slide aside the old in favor of the new. One old habit remained. The junk didn’t get tossed. Much of it accumulated in corners of the amazing new rooms called garages that city-dwellers found attached to their new suburban homes.

Tom Swift wasn’t the first to emulate, nor was his ilk confined to fiction. The occasional lucky boy with indulgent and well-to-do parents turned their homes into miniature Menlo Parks as soon as batteries and wires and bulbs appeared. L. Frank Baum wrote about his 15-year-old son Rob in 1902.

He fitted up the little back room in the attic as his workshop, and from thence a net-work of wires soon ran throughout the house. Not only had every outside door its electric bell, but every window was fitted with a burglar alarm; moreover no one could cross the threshold of any interior room without registering the fact in Rob’s workshop. The gas was lighted by an electric fob; a chime, connected with an erratic clock in the boy’s room, woke the servants at all hours of the night and caused the cook to give warning; a bell rang whenever the postman dropped a letter into the box; there were bells, bells, bells everywhere, ringing at the right time, the wrong time and all the time. And there were telephones in the different rooms, too, through which Rob could call up the different members of the family just when they did not wish to be disturbed.

(You can read more about the book Rob inspired, The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale: Founded Upon the Mysteries of Electricity and the Optimism of Its Devotees. It Was Written for Boys but Others May Read It. at Baum’s Magic Pills on my FlyingCarsandFoodPills website.)

Two generations later, the reincarnations of Rob now could rummage through those piles of junk and turn them into working objects. Newspapers loved these stories. Boy Builds Robot topped Man Bites Dog; photographers could take pictures of the robots, always goofy, ungainly, endearing piles of nuts and bolts implicitly symbolizing how American inventiveness would win the cold war. Robert Dupwe built Cog in 1954. Michael Freeman’s Rudy the Robot won first place in the 1960 Westinghouse Science Fair. The seven-foot-tall Thodar was Ronald Hezel’s 1954 project. Donald Rich’s Robetron appeared on I’ve Got a Secret in 1958. Robetron “has never learned to say “yes,” because it’s a girl robot,” said host Garry Moore with leaden 50s humor. Tellingly, every one of the teen robot makers in earlier decades were boys. Girls were almost completely shut out of access and acknowledgements in the small world of robots.

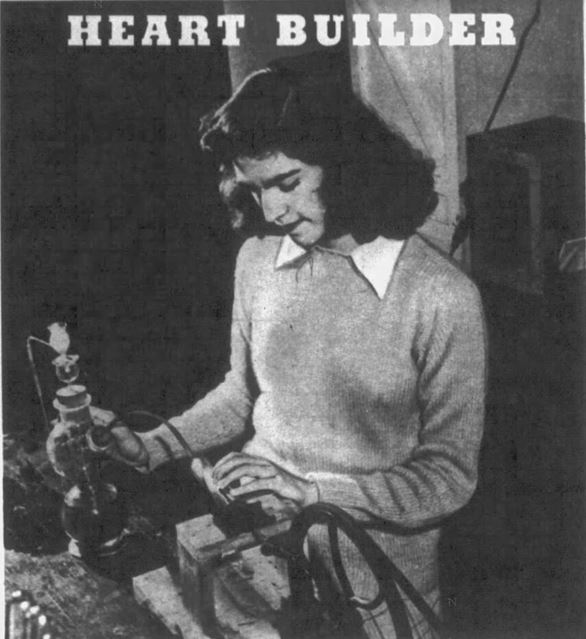

None made the national news, but one bit of brilliance was so close and so wonderful that I can’t let her slip by. “Robot Heart from the Junk Pile” read the headline in the November 25, 1945 American Weekly, a national weekly supplement to Sunday newspapers. (That headline and others that used the word “robot” are reminders that the word had a much different prewar connotation. Robot could be applied to any self-functioning mechanism, from a airplane to a traffic light. Robots might look like people, but those were a subset of the whole.) In 1944 16-year-old Alice Dale of Columbia, TN, built a “robot” heart from “lab jars, an electric motor, a tin pie plate, parts of a toy construction set, her mother’s swing machine wheel and a football pump.” She won a scholarship to nearby Vanderbilt University in the 1944 Science Talent Search and intended to become a doctor. I couldn’t trace her after that. A mechanical heart is a wonder, but not a robot. I hope a Dr. Alice of some last name fulfilled her dreams.

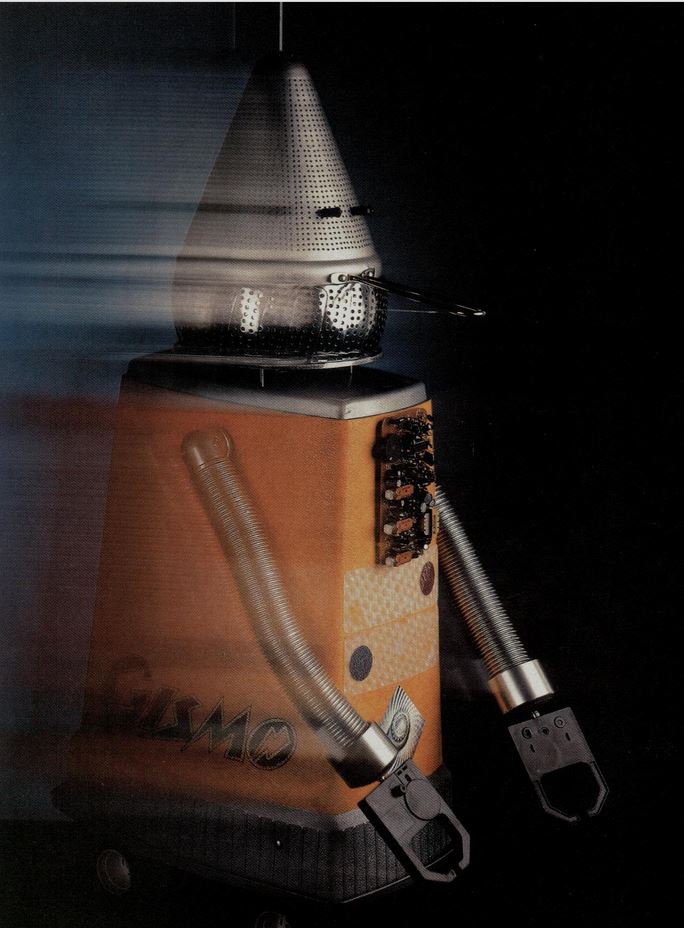

The star kid robot builder of the 1950s has to be Sherwood “Woody” Fuehrer, whose Gismo surfaced in that busy robot year of 1954 and left a legacy that stretches across a half century.

Cranston, R.I. – A cookie-passing robot with blazing eyes quietly lives in a cellar here, it was disclosed today.

Name’s Gismo and he looks pretty evil but actually he’s harmless. Just throw a switch and Gismo passes the cookies – or anything else he happens to be holding in what passes for hands.

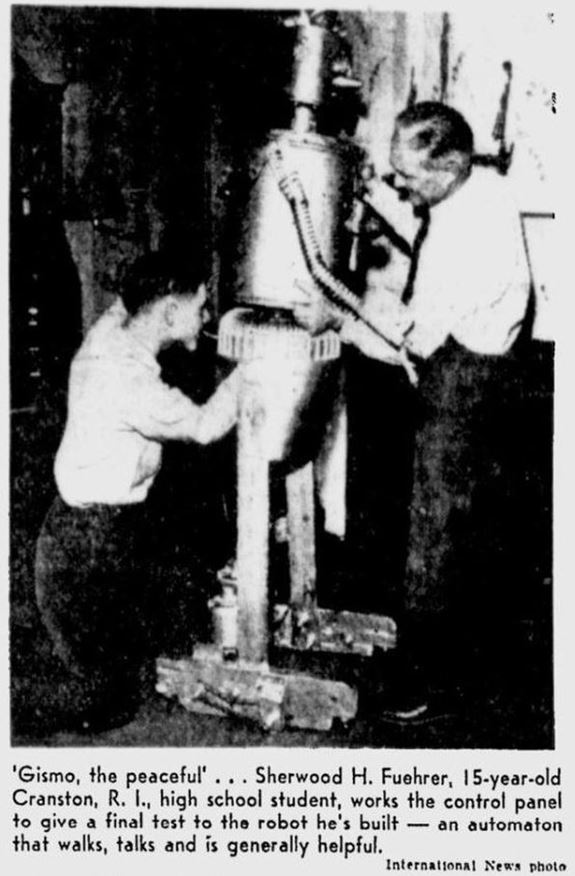

Gismo’s boss is 13-year-old scientist Sherwood “Woody” Fuehrer. He made the 5-foot, 11-inch robot out of an oil can, old transmission gear, 112-volt motor, a few discarded electric meters and other “secret” stuff. Gismo weighs 92 pounds.

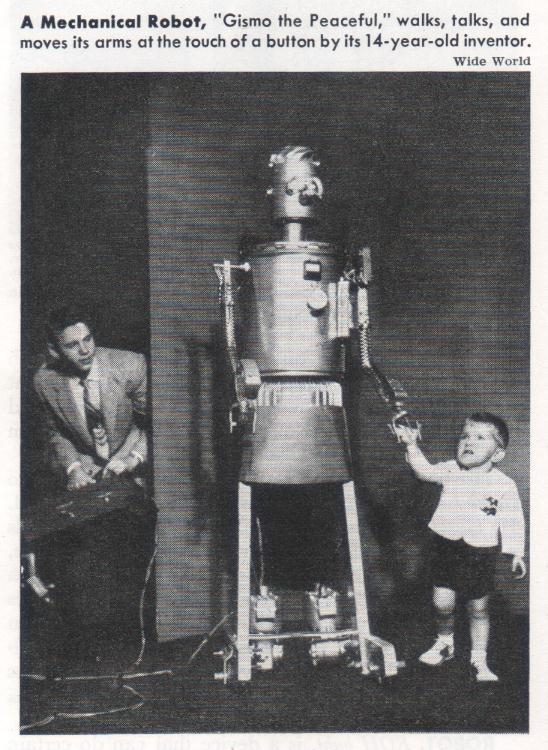

Sealing Woody’s fame was the unusual feat of getting his photo sent out over both as an AP Wirephoto (at top) and a UP Telephoto.

The two news agencies had a near lock on syndication. Woody and Gismo appeared in hundreds of papers, not just in the inaugural month of March 1954 but for a year after, goosed by Woody’s inclusion among young inventors in the Feb. 27, 1955 issue of This Week magazine, another nationally syndicated Sunday magazine. A bunch of articles made sure to mention that Gismo cost exactly $4.94 even though none of them bothered to specify what the money was spent on.

Woody later gave a detailed account of Gismo’s birth.

I had plenty of old wire and switches lying around. My hobby is ham radio and electronics, so I’d been collecting odd parts for some time. …

With the empty [pretzel] can as a start [for the body], I went to work. First came the arms, made from erector set bar. Then I installed an arm-raising assembly. The legs finished off the bottom half.

The head came next. I inserted flashlight bulbs in the oil can for eyes, and a mortar fuse for the nose.

I looked over [my father’s] box of sample [die] castings and picked out a sump for the neck, a transmission housing for the hips, and a stator for the hair. …

By this time, the arms moved, a claw opened to grasp objects, the eyes flashed, and the head buzzed. A pilot light and a flashing heartbeat adorned the body. …

The Providence Journal ran the key story after this earliest Gismo won a prize in the Rhode Island State Science Fair. That led to the wireservices descending upon suburban Cranston and that led to instant fame. Within a week, Woody and Gismo were featured on The Today Show.

I became deluged with mail. Many sent clippings. One came from the island of Guam. I received two offers to buy him. Letters came from all over the United States – boys wanting plans and girls just wanting to be friendly.

And that, I’m afraid, explains why there were no stories of postwar girl robot inventors. Expectations were wildly different and so was encouragement.

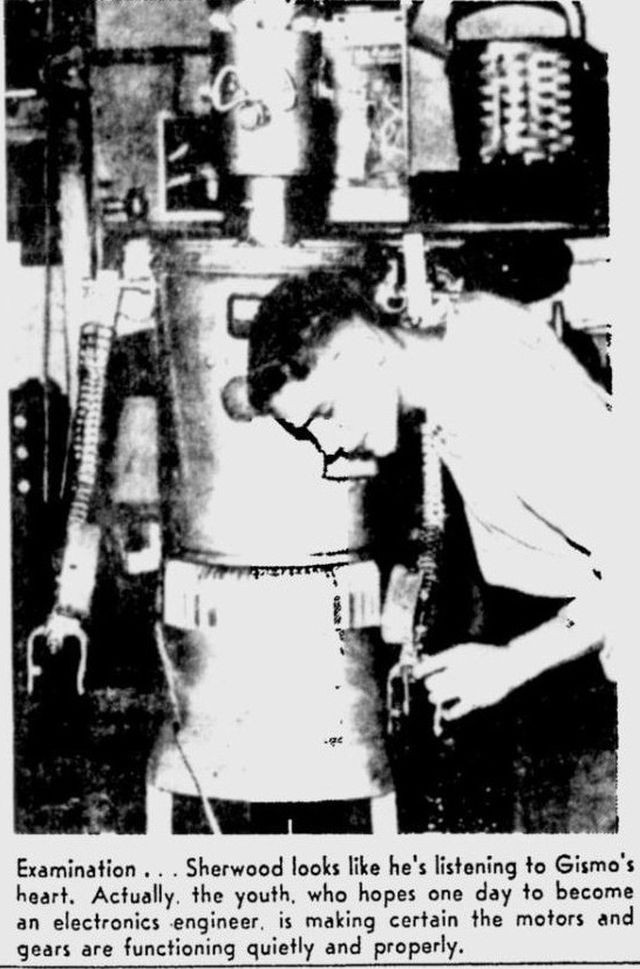

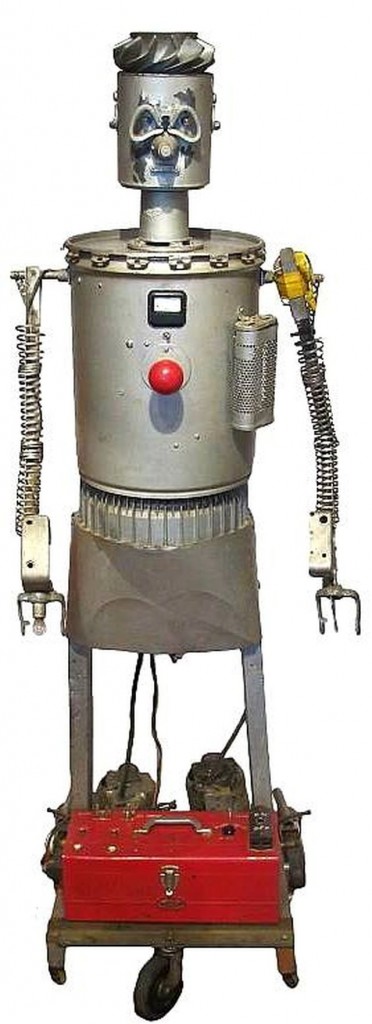

Woody continued to improve Gismo. He swapped out the pretzel can for a heavier and sturdier oil drum and made arms of aluminum. Upgrades, as they always do, caused Gismo’s cost to soar, all the way to $15. Those advances took Gismo out of the merely cute category.

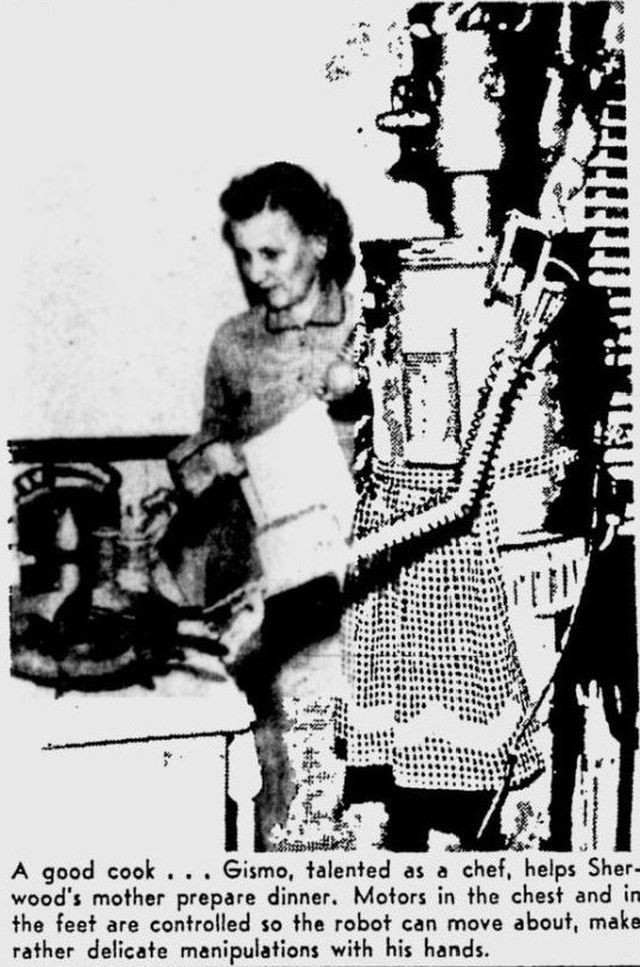

I constructed two new feet and experimented for a few weeks with arrangements of motors and belts. Finally, he rolled along like a Sherman tank, powered by a one-twelfth horsepower motor. Now nothing in the cellar was safe from his clutching hands.

I didn’t have much trouble making Gismo talk. I used a three-inch radio speaker in his head and the amplifier from the same radio in his body. I connected a wire recorder to the amplifier and Gismo could now say anything that I recorded.

The new, improved Gismo won Woody the $50 Ingenuity award at the Dearborn Industrial Arts Competition sponsored by the Ford Motor Company, another appearance on The Today Show, and a tour around the country to show off his now 150-pound robot.

|

|

|

|

Designed to be a friendly and helpful robot, Gismo got dubbed “Gismo the Peaceful” and was shown in the most benign situations conceivable, as in this picture that was his entry in a World Book Encyclopedia.

Woody finally got the ultimate accolade for a teen boy. Not just a write-up in the June 1956 Boys’ Life magazine, but a full-length article written by him (or at least published under his name), which is the source of his descriptions of building Gismo.

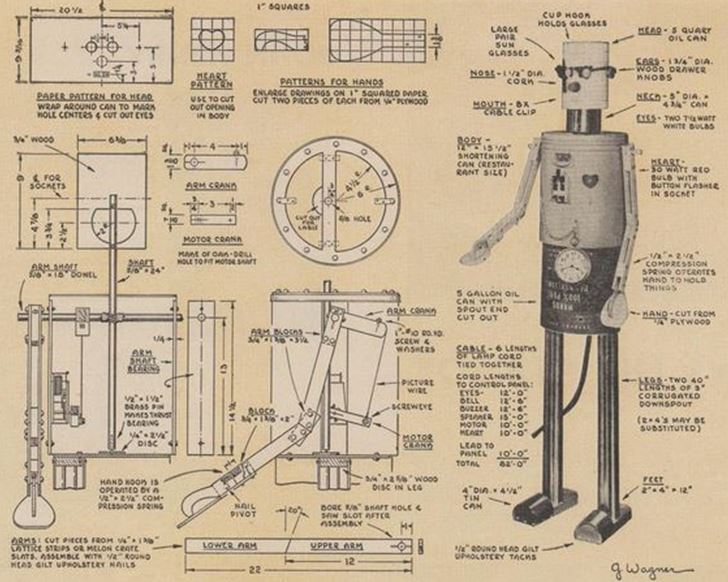

Readers wanted more. In the November 1956 issue, Glenn Wagner gave the readers instructions for making a Gismo of their own, considerably simplified of course.

Like Alice Dale, Woody went on to his nearby high-end college, Brown, pursuing a B.S. in, what else, Engineering. Reuben Hoggart of CyberneticZoo.com reports that Woody died ridiculously young, at 24 in 1964, and that seems correct. Gismo, amazingly, survived him. As of 2012 he was installed in the Ashley John Gallery in West Palm Beach, Florida as an artwork for sale at a stupefying $49,500, although their website does not list him today. Did someone buy Gismo? It wasn’t me, although I’d love to have him standing in my yard.

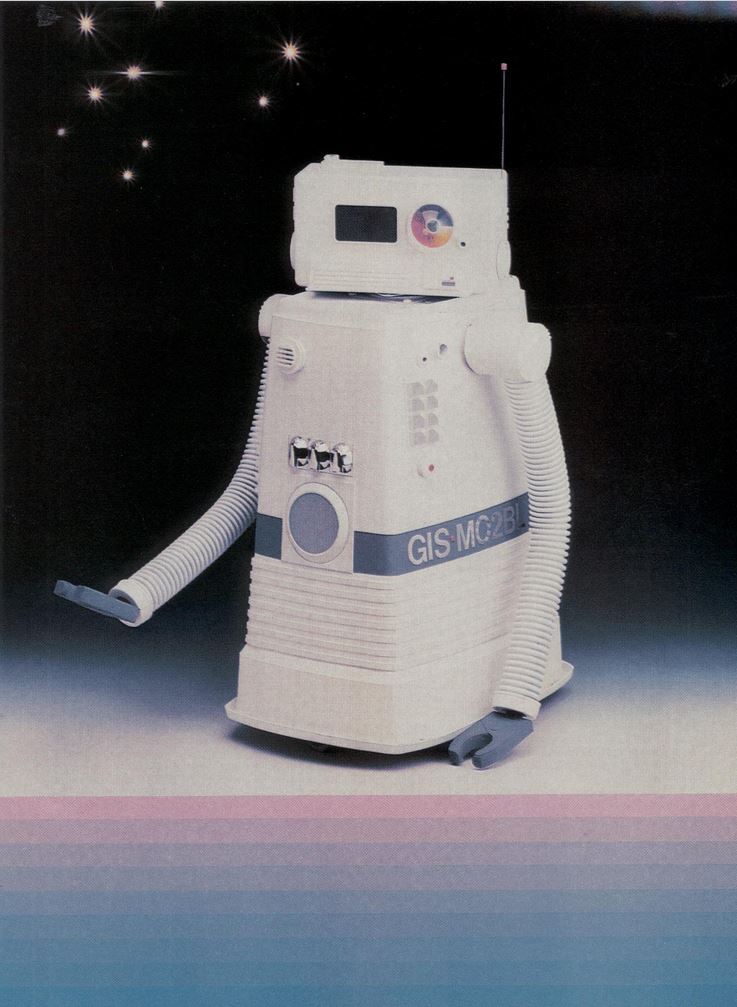

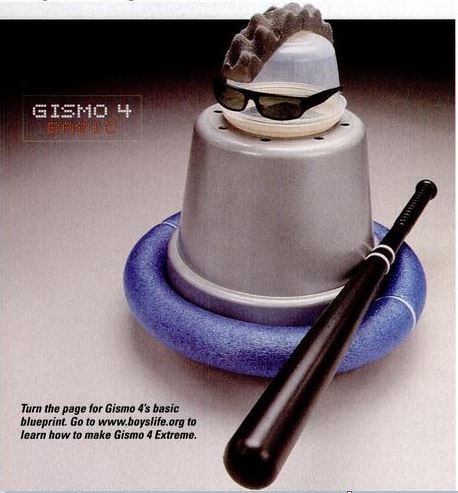

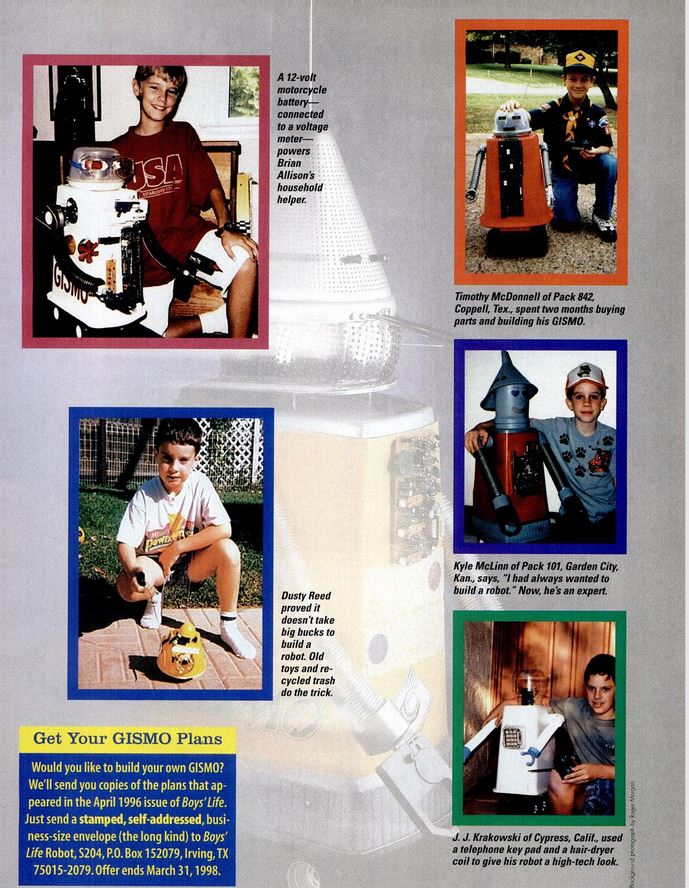

But that still isn’t the end to Gismo’s story. Boys’ Life kept bringing Gismo back in various how to build a robot stories featuring Gismos 2 through 5 (although the last was a toy out of recycled cereal boxes), along with pages of pictures sent in by readers to show off the Gismos they had built. Below are Gismos 2 (1987), 3 (1990) and 4 (2002) and a variety of Gismo 2 wannabes built by kids who look too young to even be Boy Scouts.

|

|

|

|

Today co-ed school robot teams compete in national robot competitions and attend summer robot camps. Making a robot for $4.94 out of spare parts wouldn’t get a mention in a parent’s Facebook account let alone compel competing wireservice photographers to race to the wilds of suburbia. We need something that can be constructed by ambitious and inventive teens other than haxor code. Please let it not be real viruses.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Space Conquerors!.

![1955-04-07 Elmira [NY] Star-Gazette 23 Gismo illus](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1955-04-07-Elmira-NY-Star-Gazette-23-Gismo-illus.jpg)

![1955-02-27 Minneapolis Star Tribune [This Week 9] gismo robot](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1955-02-27-Minneapolis-Star-Tribune-This-Week-9-gismo-robot.jpg)

The adoring expression on the face of that unfortunately named young man as he looks at his creation is now only seen when people gaze deep into their iPhones. Progress? I think not.

I met Woody at a science fair in Providence around 1954. Does anyone know how he died (so young)? Thanks

He died at age 23 from a brain tumor. He is buried in Fairmount Cemetery in Phillipsburg, NJ.

Thank you for finding that information, Lisa. For the record he was born on September 15, 1940 and died on February 23, 1964.

I met Woody at an electronics show in Providence in 1954. Does anyone know how he died (So young).?

His leaving for a better world is a bitter loss. Thank you for any comments.

I searched through the newspaper database as well as a Google search and saw nothing that would explain Woody’s death. Or even to confirm the age. Sorry I can’t help.

Thank you for your research. I greatly appreciate it. It is a tribute to Woody that I would think

of him 70 years after meeting him. Sic transit gloria mundi