Old School: The Iliad

A while back it was time to hit the dreaded “To Be Read” pile, and I found myself in the mood for a good, old fashioned yarn full of blood and sweat and battles with edged weapons and feats of valor and derring-do, a tale of larger than life heroes and their mighty deeds — in other words, something old school. ( I had just finished reading a volume of John Updike short stories set in suburban, middle-class Pennsylvania, so I was ready, as John Cleese used to say, for something completely different.)

While not entirely eschewing the new, in my reading choices I do tend to lean toward older, more established books and authors (test of time and all that, you know — plus, they’re usually cheaper) and this time I decided to skew just about as far in that direction as it’s possible to skew. I reached all the way down to the bottom of the stack — three millennia down — and pulled up The Iliad. (At that moment, Western Civ teachers across the land contentedly smiled in their sleep without even knowing why.) Having “little Latin and less Greek” (as in none) I chose the highly regarded Robert Fagles translation, which has been laying around the house unread for the last, oh, twenty five years.

What follows is in no sense a learned reading of The Iliad (as will immediately be apparent!), but is simply this reader’s untutored reaction to his initial encounter with one of the world’s great books. It’s rather like a mayfly’s head-on meeting with a Mack truck; the insect’s reaction may not exactly be profound, but it has no doubt that it has been hit by something too big and serious to ignore.

[Click the images for Trojan-sized versions.]

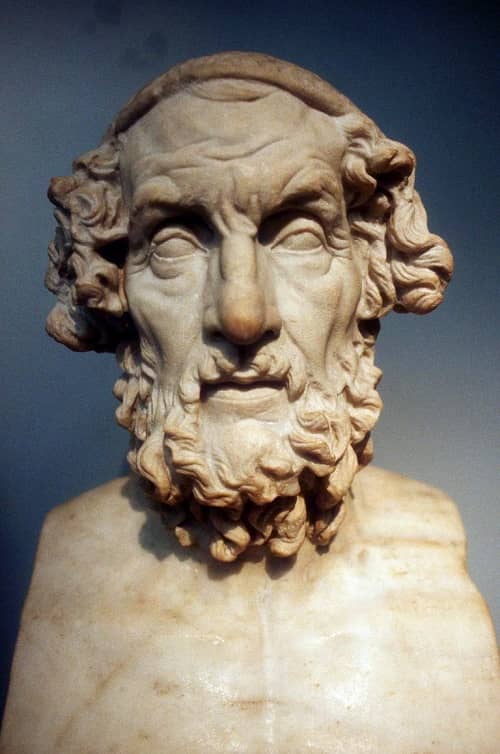

Homer

The Iliad is of course one of the foundational works of Western literature and many would assert that it is still the greatest of them all. Written by Homer (Individual genius or creative committee? Blind oral bard or literate author? Paris and Helen may be long dead, but the academic battles still relentlessly rage on), this 2,800 year old epic poem tells of the rage of Achilles when, in the tenth year of the Greek siege of Troy, he is insulted by the Greek leader Agamemnon, who has taken one of Achilles’ captives, Briseis, for himself. Achilles — the greatest of the Greek warriors — pulls himself and his own soldiers out of the battle, content to let his own side suffer disastrous defeat, all to prove how much they need him and to force Agamemnon to come and plead for his help.

Eventually, after the death of his beloved friend Patroclus at the hands of Hector, son of the Trojan King Priam, Achilles rejoins the battle and kills Hector, setting the stage for the destruction of Troy and his own death, which he knows is fated to follow almost immediately. The ruse of the wooden horse and the actual fall and sack of the city take place outside the frame of The Iliad, which ends with the funeral of Hector. (If you want the whole beginning-to-end story, from the Judgment of Paris that precipitates the war, to the final Cassandra-predicted catastrophe, read Robert Graves’ The Siege and Fall of Troy, which neatly weaves material from all of the ancient sources into a unified narrative.)

This is not Achilles. This is Brad Pitt

The Iliad‘s story is fairly straightforward, and is also familiar (in its general outlines, at least) to anyone who managed to stay awake through either their first semester of college or the 2004 movie Troy, in which Achilles is impersonated by Brad Pitt, but what was most amazing to me about this massive poem, and what forms its irreducible core, is the violence of the warfare it depicts. Living in the age of Scorsese and Tarantino, weaned on slasher movies and the westerns of Sam Peckinpah and Clint Eastwood, and having grown up with the Vietnam War playing out on the news every night of my childhood (and the endless parade of its successors playing out every night of my adulthood), I was still thunderstruck by the violence of this ancient book, truly shocked by how shocking I found it, and amazed by how utterly unromanticized its portrait of war is. There are some fine words about the honor of dying for your fatherland before battle is joined, but once the armies clash, such paper-thin pieties instantly drop away.

Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus

In the Iliad, Greeks and Trojans die in agony, screaming, pleading, weeping, groaning, despairing, terrified, futilely clawing at life as they’re “dragged down” to the “dark house” of “hateful” death. Over and over, Homer unblinkingly describes what iron and bronze can do to even the most heroic human body — spears, arrows, and swords shred bladders and livers, obliterate faces as they smash through jaws and eye sockets, shatter bones, spill entrails onto the ground, crush skulls, spatter blood and brains inside helmets. These terrifying encounters that always end in death are so intense and intimate as to have a charge that is almost erotic. The only thing I’ve ever read that even faintly approaches it is Cormac McCarthy’s postmodern Western novel Blood Meridian, and I strongly suspect that McCarthy was consciously modeling the violence in his great book on that in the Iliad.

The fact that these savage acts are rendered in verse doesn’t in the least soften or distance them — just the opposite. Indeed, the poetry makes the carnage all the more immediate (and more nightmarishly inescapable), makes it sharper than reality itself, in the way that a fevered hallucination can seem more real than everyday actuality.

Achilles and the Body of Hector

The violence in the poem is never gratuitous, however; it is in fact the whole point of the work, accomplishing as it does nothing but the destruction of all who employ it. No matter how momentarily successful either side seems to be, ultimately their violence is an uncontrollable force that inevitably uses itself up by turning back on those who wield it, to completely consume them. It is less an instrument that men use for their own ends and then cast aside when those ends are accomplished than something that they summon and that has a life and aims of its own, aims that have nothing to do with any human goals, personal or political.

Even the Gods themselves are not masters of the situation once this kind of violence has been turned loose. Throughout the Iliad the Olympians kibitz and manipulate from the sidelines and intervene in events here and there, but in the poem’s ultimate moments — moments of pain and suffering and fear and sorrow and most of all, death — the Gods withdraw and the mortals are left helplessly alone with this thing that they have called forth and cannot now dismiss. In the presence of such uniquely human destruction, the immortals can only look on, appalled and impotent.

The Walls of Troy Today

The moments of mercy and empathy in the poem, especially the heartbreakingly beautiful conclusion, when King Priam comes to Achilles to plead for the return of his son Hector’s body, are all the more moving for their sad futility. Though Achilles’ heart is touched by Priam’s grief (he instantly loves the broken, weeping old man, who reminds him of his own father, whom he knows he will never see again) and he graciously returns the body, granting the Trojans twelve days of respite from attack so they can hold the burial rites for Hector, such noble impulses can do little in a world subject to such insatiable violence. Achilles and Priam both know that nothing has been changed. The dead are still dead, Troy and Achilles are equally doomed, and conqueror and King alike are powerless, both yoked to a tragic fate that they can do nothing to alter.

Achilles and Priam, Greeks and Trojans, are all victims of the blind, capricious force that rules the world, a force that cares nothing for the hopes and aspirations of human beings, and that planted some of its own dark nature in every human heart. The whole work is a shattering consideration of the question — how much of the good and the decent and the enduring can we ever build in a world so composed?

Priam and Achilles

It is that question that made reading the Iliad rather more than I bargained for. I reached into my book pile for a classic tale of conflict and courage brimming with great deeds on an epic scale, vividly colored with the passion and blood of heroes. Homer’s great work is that indeed, but it’s also far, far more. If you’re like me and it’s one of the Big Ones that you’ve been ducking for years, be bold. Pick it up and plunge in — just be prepared to be shaken to your core.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was an appreciation of Stan Lee.

In highschool i randomly bought the translation by Stanley Lombardo. I read about a quarter of it in one night. I enjoyed it enough. But for some reason I never went back to it and its still on my shelf.

I believe someone – Ian McKellen? Derek Jacobi? – recorded the Fagles translation as an audiobook. That might be the way to do this one.

For a short time, I was doing some FB posts with comments on my day’s reading of The Iliad. With a twist.

So, things like: ‘Boy, things are looking good for the Trojans. They almost burned the ships today. I predict the Greeks will be sailing home tomorrow.’

‘Wow. Nice horse. Definitely worth knocking the walls down to drag into the city. Definitely.’

I’d like to actually do the whole book read as a series of posts like that.

I think The Iliad is one of the greats. I don’t mind The Odyssey and The Aeneid. But they’re distant seconds.

Derek Jacobi’s reading of Robert Fagle’s translation is outstanding!

McKellan did Fagle’s Odyssey. It’s not bad, but I think Jacobi’s work is much better.

Simon Callow did Fagle’s Aeneid.

I recommend listening to all three, though.

If you like the Iliad, Bob, you should give the Song of Roland a try (if you haven’t already). Not nearly as “deep” as Homer, but great bash-crash-slash fun. I read it in the Penguin Classics Dorothy Sayers translation and it moves like a bullet.

[…] Black Gate » Old School: The Iliad. The Iliad is one of my favorite works and this is a great review because it makes it sound as awesome as it is and not like some stuffy bit of academia. […]