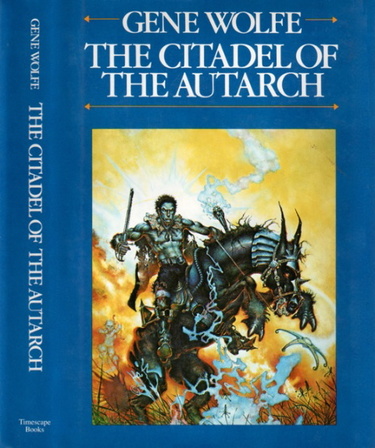

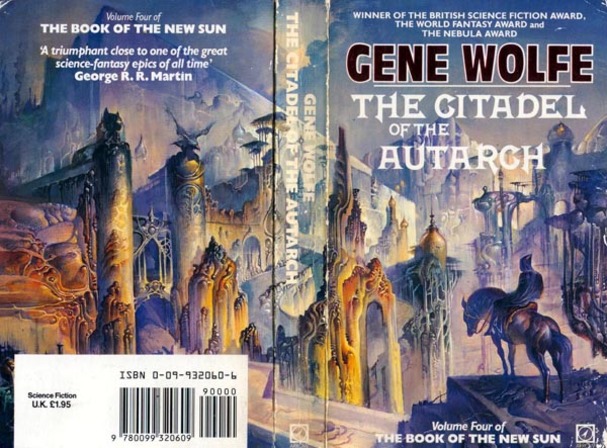

Ouroboros: The Citadel of the Autarch by Gene Wolfe

I have no way of knowing whether you, who eventually will read this record, like stories or not. If you do not, no doubt you have turned these pages without attention. I confess that I love them. Indeed, it often seems to me that of all the good things in the world, the only ones humanity can claim for itself are stories and music; the rest, mercy, beauty, sleep, clean water and hot food (as the Ascian would have said) are all the work of the Increate. Thus, stories are small things indeed in the scheme of the universe, but it is hard not to love best what is our own—hard for me, at least.

— Severian

With The Citadel of the Autarch (1983) the story ends where it began: Nessus, the great city of the Commonwealth. Severian is no longer a young torturer exiled for an act of mercy, but a figure of incredible power and importance. Realistic depictions of peace and war are interwoven with excursions into phantasmagoria. Severian encounters old friends as well as enemies, experiences mass combat, and meets the strange soldiers of the Commonwealth’s Orwellian enemy, Ascia. Told in Wolfe’s often elliptical style, there are the familiar hints of Clark Ashton Smith, the stench of Wolfe’s time during the Korean War, and a solid whiff of Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday.

With The Citadel of the Autarch (1983) the story ends where it began: Nessus, the great city of the Commonwealth. Severian is no longer a young torturer exiled for an act of mercy, but a figure of incredible power and importance. Realistic depictions of peace and war are interwoven with excursions into phantasmagoria. Severian encounters old friends as well as enemies, experiences mass combat, and meets the strange soldiers of the Commonwealth’s Orwellian enemy, Ascia. Told in Wolfe’s often elliptical style, there are the familiar hints of Clark Ashton Smith, the stench of Wolfe’s time during the Korean War, and a solid whiff of Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday.

At the end of the previous book, The Sword of the Lictor, Severian’s great sword, Terminus Est, was broken. So too, seemingly, the life-restoring Claw of the Conciliator he means to return to the religious order, the Pelerines. Searching for the blue gem’s pieces, he discovered that at its shattered heart was a simple thorn. The gem itself was mere glass.

Citadel begins with Severian continuing northward in search of the Pelerines and the front between the Commonwealth’s and Ascia’s armies. He soon meets the trailing edge of the Autarch’s armies: supply trains, cavalry patrols, and the scattered remains of the killed. As he pilfers supplies from one dead soldier he is struck by the callousness of his actions and by the contents of a letter written by the dead man to his beloved. He restores the corpse to life with the thorn from the Claw. Whether unable or unwilling to speak, the resurrected soldier travels with Severian until they finally come to a great field hospital run by the Pelerines.

Severian, it turns out, is suffering from a fever and is taken in by the ministering sisters. He strikes up a friendship with several fellow patients, a woman and three men who wish to marry her. And here, Citadel takes a storytelling detour. To choose a husband from among her suitors, Foila decides that whomever can tell the best story will win her hand. She asks Severian to act as judge. Each story has its own strengths, but it’s that of the Ascian prisoner I found the most interesting.

In order to prevent the idea of rebelling from even forming, Ascian citizens are allowed to speak in only specific approved sentences. The prisoner, Loyal to the Group of Seventeen, tells his tale in these set phrases with Foila acting as interpreter for the others.

…after a time, the Ascian began to speak: “In times past, loyalty to the cause of the populace was to be found everywhere. The will of the Group of Seventeen was the will of everyone.”

Foila interpreted: “Once upon a time …”

“Let no one be idle. If one is idle, let him band together with others who are idle too, and let them look for idle land. Let everyone they meet direct them. It is better to walk a thousand leagues than to sit in the House of Starvation.”

“There was a remote farm worked in partnership by people who were not related.”

“One is strong, another beautiful, a third a cunning artificer. Which is best? He who serves the populace.”

“On this farm lived a good man.”

“Let the work be divided by a wise divider of work. Let the food be divided by a just divider of food. Let the pigs grow fat. Let rats starve.”

“The others cheated him of his share.”

“The people meeting in counsel may judge, but no one is to receive more than a hundred blows.”

“He complained, and they beat him.”

“How are the hands nourished? By the blood. How does the blood reach the hands? By the veins. If the veins are closed, the hands will rot away.”

“He left that farm and took to the roads.”

It’s a wonderful piece of writing. Along with the other stories, each very different in style and content, this is one more element that Wolfe uses to create a world of palpable texture and vivid colors.

Following his time among the Pelerines, who don’t believe the thorn is the real Claw of the Conciliator, he is sent on a mission. He fails at it, but his eyes are opened to some of Urth’s mysteries and he learns of possible futures and other enemies. From there he enters into the ranks of the Commonwealth’s army, joining a troop of irregular riders.

Wolfe’s depictions of the war-brutalized land and the battles is as affecting as any I’ve read before. The smell of burnt timber and bodies spills off the page. Bodies are cloven, animals torn apart by weapon-fire, and above all, a spirit of chaos and frenzy reigns.

If the cherkajis were lightly armed, we were armed more lightly still. Yet there was a magic in the charge more powerful than the chants of our savage allies. The wildfire of our weapons played along the distant ranks as scythes attack a wheat field. I lashed the piebald with his reins to keep from being outdistanced by the roaring hoofs I heard behind me. Yet I was, and glimpsed Daria as she shot past, the flame of her hair flying free, her contus in one hand and a sabre in the other, her cheeks whiter than the foaming flanks of her destrier. I knew then how the custom of the cherkajis had begun, and I tried to charge faster still so that she should not die, though Thecla laughed through my lips at the thought. Destriers do not run like common beasts—they skim the ground as arrows do air. For an instant, the fire of the Ascian infantry half a league away rose before us like a wall. A moment later we were among them, the legs of every mount bloody to the knee. The square that had seemed as solid as a building stone had become only a crowd of frantic soldiers with big shields and cropped heads, soldiers who often slew one another in their eagerness to slay us. Fighting is a stupid business at best; but there are things to be learned about it, of which the first is that numbers tell only in time. The immediate struggle is always that of an individual against one or two others. In this our destriers gave us the upper hand—not only because of their height and weight, but because they bit and struck out with their forefeet, and the blows of their hoofs were more powerful than any man save Baldanders could have delivered with a mace.

Fire cut through my contus. I dropped it but continued to kill, slashing left, then right, then left again with the falchion and hardly noticing that the blast had laid open my leg.

In the calm following the battle, Severian meets the Autarch once again. He eventually confirms all the hints that have been offered up over the series: the torturer is to be his heir. In order to restore the sun and reopen space travel to humanity, an Autarch must face a mysterious challenge. If judged worthy, space will be reopened, if not, he will be unmanned and unable to father a natural heir. The present Autarch, the first to take up the challenge in centuries, has failed. In Severian he knows there is someone capable of passing the test.

After a series of adventures with the Autarch Severian falls into the hands of an old enemy, Agia, now part of the rebel army led by Vodalus. During his imprisonment among them the Autarch dies, and with a grisly act Severian becomes his replacement. There are a few more struggles for the new Autarch among his captors and the surrounding Ascian forces, but they are minor inconveniences for the newly-empowered ruler.

After a series of adventures with the Autarch Severian falls into the hands of an old enemy, Agia, now part of the rebel army led by Vodalus. During his imprisonment among them the Autarch dies, and with a grisly act Severian becomes his replacement. There are a few more struggles for the new Autarch among his captors and the surrounding Ascian forces, but they are minor inconveniences for the newly-empowered ruler.

In the end, as I wrote in the beginning, Severian is back in Nessus. Once again he meets old comrades. Several important things that have puzzled him since leaving the guild tower are finally answered. The book, and the therefore the series, ends with Severian, now Autarch, exploring tunnels beneath the Citadel of Nessus in search of the mysterious girl he met there years earlier.

I’m going to need some time to digest what I’ve just finished reading. Wolfe’s work is exciting, dense with symbolism, and written beautifully. Exactly what it all means, I can’t say, nor can I even say whether that’s achievable. I am sad I’ve begun this adventure so late in my life; these are books that warrant, no, demand multiple readings. Only on the most obvious level are they just one more entry into the catalogue of dying Earth tales (though they are among the best examples of the genre). The Urth of the New Sun is a story of renewal through sacrifice and knowledge. It’s simply one of the best collections of books I’ve read and reviewed in my years here at Black Gate, but I still need to think about them before fully committing my thoughts here. So, next week, a wrap up and review of all four books.

Previous reviews of the Urth of the New Sun

The Shadow of the Torturer (1980)

The Claw of the Conciliator (1981)

The Sword of the Lictor (1982)

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now (actually, I’m writing about Westerns right now).

At some point, I’d highly recommend following up with Urth of the New Sun, which is a really great capstone or coda to the original series.

This reminds me that I still need to reread these books at some point, plus the Long Sun and Short Sun series.

“I am sad I’ve begun this adventure so late in my life; these are books that warrant, no, demand multiple readings.”

…and you started late on Merritt as well. Better late than never!

Seriously, the “New Sun” series absolutely warrants–and rewards–multiple readings. It’s mind-boggling how much Wolfe crammed into it all. Layers upon layers, yet I as a teenager thoroughly enjoyed it.

@JoeH that was my original plan. I’ll have to read it later, definitely.

@Deuce – Right, and don’t even let me get started on a host of other authors. That accessibility as “just” and great story is part of what makes it so good. The symbolism, etc. doesn’t overwhelm Wolfe’s storytelling.