Space Conquerors!

Since 1911, boys have looked forward to the monthly appearance of Boy’s Life. I was a scout from 1961 through 1968, when the magazine was as large as Life or Look and almost as fat, a cornucopia of articles, scouting tips, stories, and comics. I saw Arthur C. Clarke’s “Sunjammer” in the March 1964 issue, a full year before the adult sf mags reprinted it. The editors at Boy’s Life stayed consistently more friendly to science fiction than virtually any other mainstream magazine in the 50s and 60s. Robert Heinlein serialized Farmer in the Sky and The Rolling Stones there and he and Asimov had books adapted into comics. For me the big draw were the Time Machine stories about the Polaris Patrol who discovered, what else, a time machine and explored the past and the future. Written by the father son team of Donald Monroe and Keith Monroe under the name of Donald Keith, a hardback version of their serialized Mutiny in the Time Machine might have been the first science fiction book I owned.

So how is it possible that I have zero memory of Space Conquerors!?

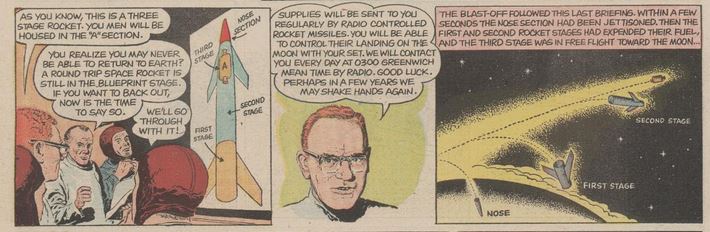

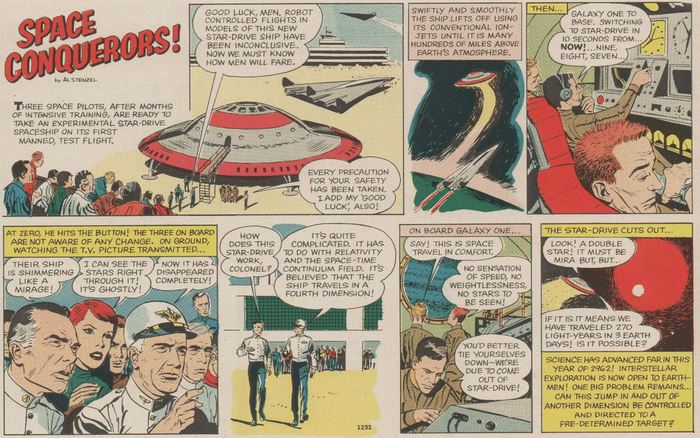

Space Conquerors! ran for a full twenty years, from 1952, when a simple rocket trip to Mars was nearly unimaginable, to 1972, when their flying saucer casually strolled alien star systems. The science was an odd mix of realism and convenience. That first rocket to Mars could go faster than the speed of light but a later space ship, built in 2054, was deemed a marvel because it could travel at half the speed of light. It needed a proper eight years to get to get to Alpha Centauri from the moon. Or perhaps the marvel was that a 1957 sequence strives for an educationally accurate first trip to the moon, but somehow is set in 2057, three years after the star ship set sail.

Tying continuity to the real space program must have seemed a drag; those guys never got anywhere. In 1962 the team acquired its flying saucer with an experimental space-time drive that worked on the solid, time-honored principle that giant space aliens are worth any amount of scientific fudging.

Blame it all on Al Stenzel. Al was the Art Director for Johnson and Cushing, a firm started during the Depression to sell comic strip-style ads to newspapers. R. C. Cola and Nestlé Toll House cookies and Raisin Bran and a hundred others had cheerful characters cavort through vignettes touting the delicioushood of their products. The top comic artists of the day could be found at the Johnson and Cushing offices, looking for some quick extra pay at ten times the normal comic book page rate. Young up-and-comers went there to seek their fortunes. Tom Heintjes described a perhaps typical scene for the Hogan’s Alley comics history magazine:

When Dik Browne ran through the lobby shrieking, his bloody shirt tattered and flapping in his wake. Al Stenzel, art director at Johnstone and Cushing, screamed at Browne as he chased him with a bullwhip. “Don’t you ever bring work like that in here again!” A job-seeking artist looked on, his trembling hands clutching a portfolio case. As he eyed the exit, Browne and Stenzel stumbled back into the room, laughing uproariously. Browne pulled off the mercurochrome-stained shirt and put it away until the next time they would haze a job applicant. Welcome to Johnstone and Cushing.

As the saying goes, it’s all fun and games until somebody loses an eye and financially speaking the eye got poked the early 1950s when newspapers stopped carrying ad cartoons. To replace the lost revenue somebody had the bright idea of creating a comics section for a magazine and Boy’s Life bit. In their September 1952 issue the “Boy’s Life Color Section – 8 PAGES of Fun – Adventure – Excitement” debuted with Pee Wee Harris, The Story of Creation, Mog-An-Ah the Mound Builder, Old Timer Tales of Kit Carson, Scouts in Action, How to Make It…,, and an ad page alongside Space Conquerors! Stenzel clearly sought to hit every possible tween boy hot button.

Nobody spends twenty years writing a science fiction adventure strip without sticking a robot in somewhere and that time arrived in late 1965. The Space Conquerors did very little conquering; their ship mostly bounced around the universe and crash landed repeatedly, prefiguring Lost in Space by a few years. Escaping an alien craft, their flying saucer lands on a strange planet (“completely lost among the millions of uncharted galaxies in outer space”) where they are attacked by spy spheres. A glob-like alien rescues them and takes them to a cave where an ancient and human alien is hiding. (Think of the odds of finding a human among millions of uncharted galaxies!) The ship’s linguist takes a few weeks to learn his language – an unfathomably realistic event dropped in out of nowhere and never repeated- and hear his story.

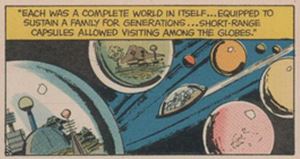

Many years earlier a bacterial plague made everybody on the surface melt into goo. The survivors fled into space in anti-gravity globes.

|

|

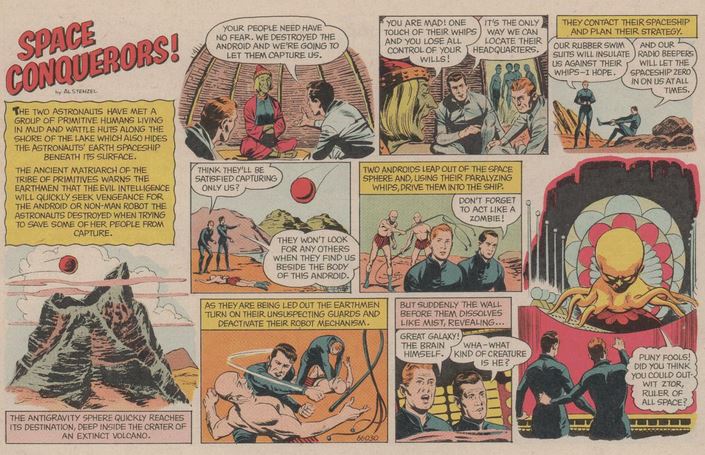

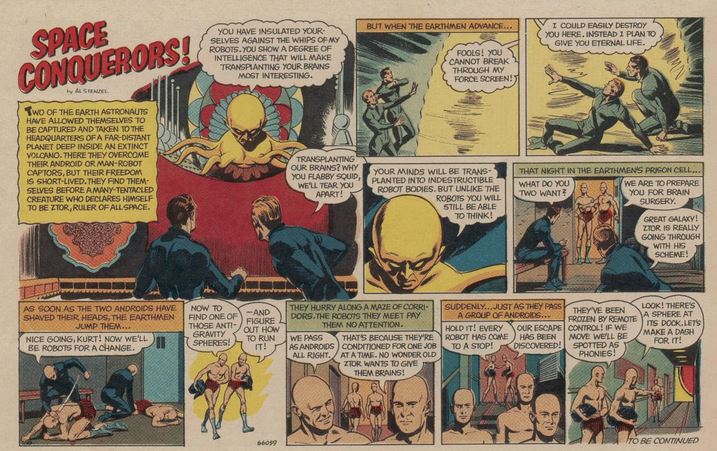

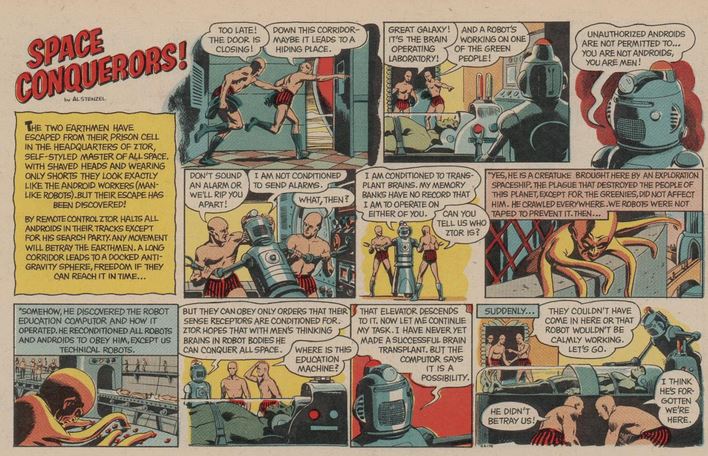

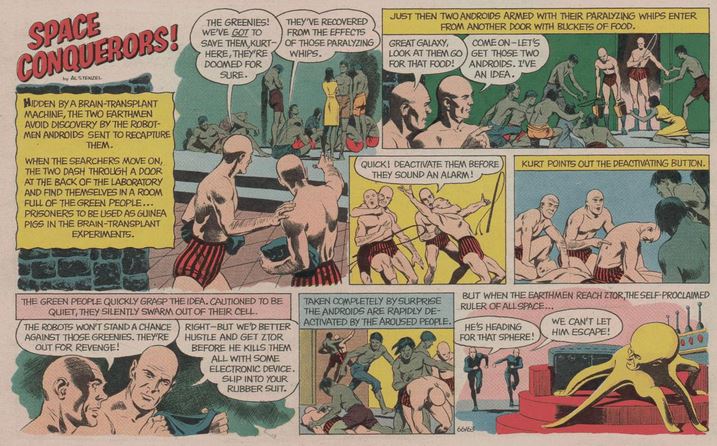

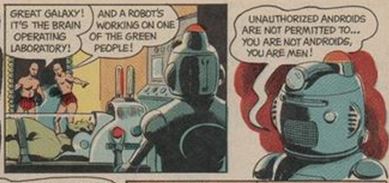

Robots worked the surface of the planet to keep it ready for the population’s return when and if the plague disappeared. Then more bad news. A fiendish space octopus (or maybe hexopus) – Ztor, Ruler of All Space – found the planet and took over the robots. Robots are unfortunately robots. They do their jobs but aren’t programmed to think for themselves. Don’t ask why he doesn’t just reprogram them: what’s the fun in that? Rather he has some robots, well, some androids, experiment on a few green people that lived through the plague and try to transplant their brains into the androids’ bodies.

Here’s where it gets confusing. Stenzel’s script has metal robots and also androids with human skin covering mechanical insides. Are the metal robots from the planet and the androids from Ztor? That makes sense to me, except that the androids look exactly like earth (i.e. white) humans. Why would Ztor do that? Moreover, if Ztor’s androids are advanced enough to do brain transplants, you wouldn’t think they’d need brain transplants. Ztor says he wants to transplant the earthmen’s brains into indestructible robot bodies but the artist shows the recipients not as the metal robots but as the androids.

I shouldn’t overthink it. In a tradition dating back at least to Buck Rogers, the humans impersonate the androids who exactly resemble them to overthrow Ztor.

Here are a few episodes out of the middle the series that show the robots and androids, along with Ztor and the green people, enough to give you its flavor

|

|

|

|

A happy ending? You’d think so. But Stenzel ends with a jaw-dropping twist that I wouldn’t believe the editors at Boy’s Life would ever allow in their pages. In the ensuing space battle, Ztor blows up a giant city on the surface, which triggers a long-dormant volcano, which destroys every power plant, which cuts the anti-gravity beams to the space globes, which causes them all to fall, burning “like meteors as they plunged down through the atmosphere.” The green people are equally doomed by the volcano. In a matter of a couple of panels the entire planet’s population has been wiped out by the heroes do-gooding. Even the most cynical authors of the nascent New Wave stories didn’t take their endings that dark. Kids these days – they have it soft. We walked uphill to and from school and got home just in time to bear the weight of genocide. No wonder why our generation turned out the way it did.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Gyro, Bazark, Ruffnik, and Oom-a-Gog.

[…] BOPPING AROUND THE GALAXY. Steve Carper helps Black Gate readers remember the “Space Conquerers!” comic strip. (Or in my case, provides a first-time […]