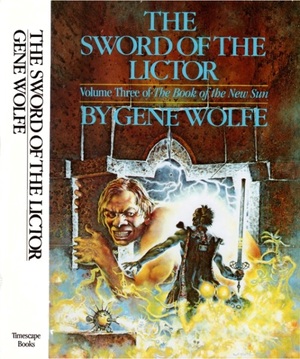

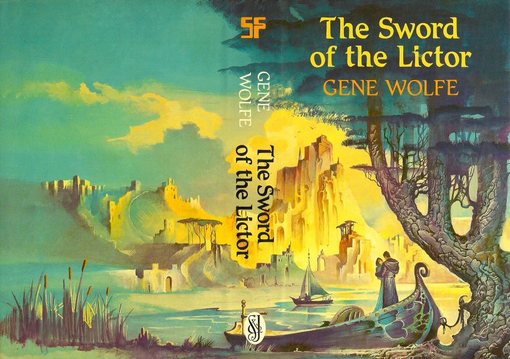

In Which Severian Becomes Human: The Sword of the Lictor by Gene Wolfe

Severian has finally arrived in the fortress town Thrax and taken up his duties as lictor, or “he who binds”, and jailor. More importantly, he serves in his trained capacity as torturer and executioner. It is his latter duties that lead to a rift between Severian and Dorcas. No matter how rationally he makes his case for legal torture and execution, she is more and more disturbed by his work. Eventually she leaves him and takes up residence in a tavern.

Severian has finally arrived in the fortress town Thrax and taken up his duties as lictor, or “he who binds”, and jailor. More importantly, he serves in his trained capacity as torturer and executioner. It is his latter duties that lead to a rift between Severian and Dorcas. No matter how rationally he makes his case for legal torture and execution, she is more and more disturbed by his work. Eventually she leaves him and takes up residence in a tavern.

His refusal to employ his guild talents for the personal desire of Thrax’s ruler leads him to flee northward — that and the fiery salamander sent to kill him by an agent of his old nemesis, Agia. Severian hopes to return the life-restoring gem, the Claw of the Conciliator, to the traveling sisterhood from which Agia stole it back in the first book, The Shadow of the Torturer. With the revealing of several dire secrets, Dorcas leaves Severian to return to Nessus and uncover the truth of her past.

1980’s The Shadow of the Torturer is a coming-of-age tale of Severian’s passage into young adulthood and out of the safe confines of his guild’s tower. While Severian’s constant withholding of information makes his narration unreliable, the book still flows in a generally normal fashion — Severian has adventures during which he journeys from point A to point B.

1981’s The Claw of the Conciliator reads like little more than a series of someone else’s dreams and nightmares. There are powerful passages, but like dreams, their potency comes not from basic storytelling, but strange imagery and psychologically dislocating events. I’m still not sure how much of Wolfe’s story eluded me, even thinking back on it now, but there are sequences that I will not forget any time soon.

With 1982’s The Sword of the Lictor Severian’s story returns to a more straightforward narrative. The events in Thrax propel Severian into a series of adventures that, on the surface at least, appear unremarkable. He fights an alzabo, a terrible monster capable of speaking in its victims’ voices and luring their loved ones to its waiting maw. He rescues a young boy, also named Severian, only to lose him to a band of sorcerers, necessitating more fighting. It is during Severian’s run-in with a revivified tyrant from Urth’s distant past that his adventures become more evidently symbolic.

The tyrant, named Typhon, first encountered as a withered two-headed corpse inside a building from ancient days, is accidentally restored to life by the two Severians. Typhon plans to reclaim suzerainty over Urth and the heavens. To do this he intends to use Severian as his representative. From a chamber at the top of a titanic statue, Typhon offers the young torturer the throne of all Urth. The echoes of the temptation of Christ in the Gospels are loud, though Severian’s ultimate response to his tempter is more sanguine. This event, ongoing intimations that Severian is to play some great role in the renewal of Urth’s dying sun, his healing and resurrection of several people, make it clear he is evolving into a messiah figure.

The tyrant, named Typhon, first encountered as a withered two-headed corpse inside a building from ancient days, is accidentally restored to life by the two Severians. Typhon plans to reclaim suzerainty over Urth and the heavens. To do this he intends to use Severian as his representative. From a chamber at the top of a titanic statue, Typhon offers the young torturer the throne of all Urth. The echoes of the temptation of Christ in the Gospels are loud, though Severian’s ultimate response to his tempter is more sanguine. This event, ongoing intimations that Severian is to play some great role in the renewal of Urth’s dying sun, his healing and resurrection of several people, make it clear he is evolving into a messiah figure.

Then there’s his growing empathy. Severian’s continued and increasing exposure to other people and their sorrows deepens his distaste for his craft and kindles a need to help and protect. Oh, he downplays it and brushes it off with excuses, but in the end he still risks death several times in order to save another’s life.

At some point Severian is imprisoned by villagers in thrall to the mysterious ruler of a nearby castle. They take the Claw from him and send it to the tower. This leads to him plotting with some primitive tribesmen an assault on the castle once he bluffs his way in on the strength of his position as lictor of Thrax. Within the walls he finds terrible horrors, old companions, and answers to questions that only raise more questions. In the end, as in the previous volumes, Severian offers his readers the chance to bail on continuing with his story.

Here I pause. If you have no desire to plunge into the struggle beside me, reader, I do not condemn you. It is no easy one.

Of the three books, this is the one I’ve outright enjoyed the most. There are several propulsive action set-pieces filled with flames, monsters, and flashing swords. I shamefacedly admit to being wholly unprepared to encounter their like within Wolfe’s densely written stories. Simultaneously, there’s tremendous worldbuilding going on on nearly every page. Much like M. John Harrison in his dying Earth series Viriconium (reviewed by me here), Wolfe clearly sees no need to explain everything (or maybe anything), instead allowing the reader to be overcome by a wealth of description and weirdness.

As a middle book The Sword of the Lictor is incapable of standing on its own, and, as with Severian, for every answer the reader receives, another one or two are raised. The thing about it is, even if Wolfe fools me and leaves me hanging, and all remaining secrets unrevealed, I don’t think I’ll care. This book is one of the most satisfying I’ve read this year. Severian is an enthralling and fascinating character, the scope and scale of Wolfe’s world is tremendous, and, above all, his writing is beautiful. If I’ve given so few examples of these things it’s because I am terribly loath to reveal too many of the book’s wonders. So stick around, and next week I’ll be back with the final volume of the Book of the New Sun, The Citadel of the Autarch.

Previous reviews of the Urth of the New Sun

The Shadow of the Torturer (1980)

The Claw of the Conciliator (1981)

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now (actually, I’m writing about Westerns right now).

Glad to hear things are straightening out in your reading! Wolfe’s alzabo is one of the great SFF monsters. “Lictor” was originally just the first half of “Autarch”, but Wolfe’s publisher decided it was too long and the split was made.