A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

I reached out to some friends to help me with A (Black) Gat in the Hand, as I certainly can’t cover everything and do it all justice. Our latest guest is author and fellow Black Gater, Joe Bonadonna. Last week, Joe delivered an in-depth look at hardboiled adaptations on the silver screen. So, here’s part two!

Hardboiled Film Noir: From Printed Page to Moving Pictures (Part Two)

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” — Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

And now, on to Raymond Chandler, one of the two writers who inspired my Heroic Fantasy, the other being Fritz Lieber, another pulp magazine maestro. Considered by many to be a founder of the hard-boiled school of detective fiction, along with Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain and other Black Mask writers, Chandler had been an oil company executive who turned to writing after he lost his job during the Great Depression.

And now, on to Raymond Chandler, one of the two writers who inspired my Heroic Fantasy, the other being Fritz Lieber, another pulp magazine maestro. Considered by many to be a founder of the hard-boiled school of detective fiction, along with Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain and other Black Mask writers, Chandler had been an oil company executive who turned to writing after he lost his job during the Great Depression.

To me, his prose is pure poetry, his use of simile and metaphor, his imagery and turn of phrase are top notch. His novel, The Big Sleep, was turned into a motion picture in 1946, starring Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe. His Lady in the Lake (1947) became an interesting vehicle for Robert Montgomery (the father of Bewitched’s Elizabeth Montgomery.) Farewell, My Lovely was first filmed as Murder, My Sweet (1944), starring Dick Powell. Chandler’s novel, The High Window, was filmed twice: first as Time to Kill (1942) and again in 1947 as The Brasher Doubloon. Chandler also had a lucrative career as a Hollywood screenwriter.

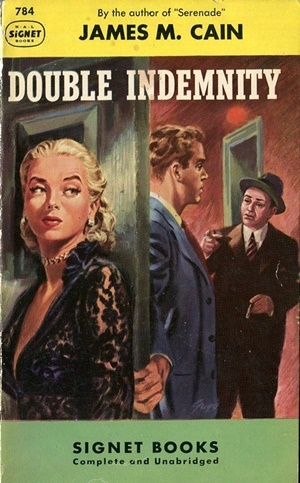

In 1944 he scripted (along with director Billy Wilder) James M. Cain’s masterpiece, Double Indemnity, wrote an original screenplay called The Blue Dahlia (1946), and co-wrote (along with Whitfield Cook and Czenzi Ormonde) the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), which was based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, the author of The Talented Mister Ripley and Ripley’s Game.

For me, the 1940s also gave us the last of what I consider to be the truly great gangster films of Hollywood’s Golden Age. High Sierra, released in 1941 and based on the novel by W.R. Burnett, was a departure from the usual gangster epic, in that it portrayed a much more sympathetic criminal, Roy Earle (played by Humphrey Bogart.)

Bogart also played the character of Vincent Parry in Dark Passage (1947), which was written for the screen by David Goodis, who adapted his own novel. Another film, based on the play by Maxwell Anderson, was 1948’s Key Largo, the perfect blend of old-school gangster and the new wave of film noir, and it was a tour de force for Bogart, Edward G. Robinson and Claire Trevor.

The powerful White Heat, from 1949, based on the story by Virginia Kellogg, was James Cagney at his best. In the history of crime and gangster films, Cagney’s Cody Jarrett remains one of the most brutal, heartless gangsters, and one with a mother fixation, to boot! And then there’s Richard Widmark’s star-making film debut as Tommy Udo in Kiss of Death (1947), taken from a story by Eleazar Lipsky. Udo is another one of the great, cinematic psychopaths, and in one unforgettable scene he pushes an old woman confined to a wheelchair down a flight of stairs.

The 1940s were the best years for film noir, a great showcase for the novels and stories upon which they were based—and for the writers of the original source material, as well. Some of what I believe to be the seminal films of that decade are: The Letter (1940), another film based on a Broadway play, this one by W. Somerset Maugham; This Gun for Hire (1942), from Graham Green’s great novel (published in Britain as A Gun for Sale); and Laura (1944), adapted from the novel by Vera Caspary.

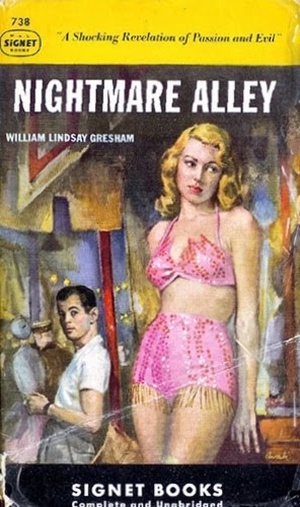

The Killers (1946) was partly based on the story by Ernest Hemingway; Nightmare Alley (1947) is a pretty faithful adaption of William Lindsay Gresham’s novel, although the film was toned-down and given a happy ending. It starred Tyron Power in an excellent performance as a carnival barker who becomes a big-time, phony spiritualist. I Wake Up Screaming (1941) came from the pages of Steve Fisher’s novel. They Live By Night (1944) was based on the famous novel Thieves Like Us, by Edward Anderson. Marty Holland’s novel, Fallen Angel, arrived on the big screen in 1945. The year 1948 gave us Naked City, from a story by Malvin Ward, while the origin for 1949’s Thieves’ Highway was A.I. Bezzerides’ novel, Thieves’ Market.

The Killers (1946) was partly based on the story by Ernest Hemingway; Nightmare Alley (1947) is a pretty faithful adaption of William Lindsay Gresham’s novel, although the film was toned-down and given a happy ending. It starred Tyron Power in an excellent performance as a carnival barker who becomes a big-time, phony spiritualist. I Wake Up Screaming (1941) came from the pages of Steve Fisher’s novel. They Live By Night (1944) was based on the famous novel Thieves Like Us, by Edward Anderson. Marty Holland’s novel, Fallen Angel, arrived on the big screen in 1945. The year 1948 gave us Naked City, from a story by Malvin Ward, while the origin for 1949’s Thieves’ Highway was A.I. Bezzerides’ novel, Thieves’ Market.

The 1940s were also interesting because the exteriors for many films were shot on location in various cities, moving from the studio to the real world. This gave the films a more grim, realistic and gritty look, almost like that of a documentary. This visual trend continued into the 1950s as more and more films left the confines of the studio set and were “shot outdoors.”

The 1950s:

With the Korean War and the ensuing Cold War, new elements and themes were introduced to film noir. While this genre and style of filmmaking were still going strong, the cinematic science fiction boom had begun as the world entered into the Atomic Age. And I will argue that film noir found its way into other genres, as well, such as the film version of Jack Finney’s novel The Body Snatchers, the now classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956); and even westerns like Day of the Outlaw (1959), from the novel by Lee Wells.

Gangsters and good old cops and robbers were still popular in the 1950s, especially on television, but now the heist film became its own thing, and more private eyes and detectives entered our cinematic universe. A number of important films of that decade were not based on novels or short stories, but on original screenplays, Side Street (1950); Panic in the Streets (1950), which was Jack Palance’s film debut; and Pick Up on South Street (1953.) Still, Hollywood in the 1950s was cranking out some excellent films based on popular novels of that era.

First I want to mention the underrated Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye from 1950, another mash-up of old-school gangster and film noir starring James Cagney, and based on the novel by Horace McCoy, who also wrote They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Two of the great heist films of that era were The Asphalt Jungle (1950), from W.R. Burnett’s novel; and The Killing (1956), which was based on the novel Clean Break, by Lionel White. The decade also brought us Night and the City (1950) from the novel by Gerald Kersh; Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), adapted from the novel Night Cry, by William L. Stuart; On Dangerous Ground (1951), based on the novel Mad with Much Heart, by Gerald Butler; and The Blue Gardenia (1953), taken from the novella by Vera Caspary.

1953 gave us The Big Heat, written by former crime reporter Sydney Boehm, based on a serial by William P. McGivern which appeared in the Saturday Evening Post and was published as a novel in 1953; in this film a vicious, sadistic Lee Marvin likes to burn women with cigarettes, and even throws a pot of boiling coffee into the face of my favorite femme fatale, Gloria Grahame. While the City Sleeps (1956) was based on the novel The Bloody Spur, by Charles Einstein; it’s the true story of the Lipstick Killer, William Heirens.

The Burglar (1957) was adapted for the screen by David Goodis, who wrote the original novel. Odds Against Tomorrow, made in 1959, was based on the novel by William P. McGivern. There were a number of other great films of the post-Korean War years—featuring all types of gangsters, molls, psychopaths, and crooked politicians . . . and of course, private eyes.

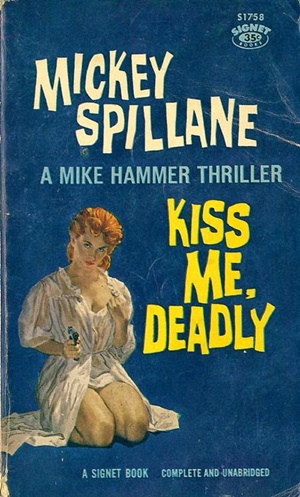

I’m a big fan of Mickey Spillane, who often gets a bum rap from a lot of people I know, but he was a pulp writer with an interesting background in publishing. This article on important crime novels and their cinematic descendants wouldn’t be complete without mentioning him. Spillane started out as a writer for comic books, concocting adventures for major 1940s comic book characters, including Captain Marvel, Superman, Batman and Captain America.

I’m a big fan of Mickey Spillane, who often gets a bum rap from a lot of people I know, but he was a pulp writer with an interesting background in publishing. This article on important crime novels and their cinematic descendants wouldn’t be complete without mentioning him. Spillane started out as a writer for comic books, concocting adventures for major 1940s comic book characters, including Captain Marvel, Superman, Batman and Captain America.

He also wrote two well-received children’s books, The Day the Sea Rolled Back (1979) and The Ship That Never Was (1982); he received an Edgar Allan Poe Grand Master Award in 1995. Although his first Mike Hammer novel, I, The Jury, was published in 1947, it didn’t make it to the big screen until 1953. This was followed by Kiss Me, Deadly (1955) and My Gun is Quick (1957.)

In 1963 Spillane portrayed his hard-boiled, tough-talking, no-nonsense Mike Hammer in The Girl Hunters, based on his novel. As far as I know Spillane is the only author to have played one of his/her own characters in a motion picture.

A side note here: for fans of TV’s Perry Mason, I recommend four very good films featuring Raymond (Perry Mason) Burr and William (Hamilton “Ham” Burger) Talman. First is 1947’s Desperate, an original screenplay featuring an excellence performance by Burr in the role of a hard-core hoodlum.

In 1948, Burr played a corrupt cop in Pitfall, based on the novel The Pitfall, by Jay Dratler. Talman himself starred in two films I enjoyed: first, Armored Car Robbery (1950), an original screenplay, where he gave a fine performance as a brutal crook; and The Hitch-Hiker (1953), in which he played a cold-blooded, one-eyed killer.

This film was inspired by the real-life crime spree of the psychopathic murderer Billy Cook. It’s based on a story by blacklisted Out of the Past screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring (who did not receive screen credit).

Epilogue

Gangsters, cops, private eyes and film noir first invaded television in the 1950s. Some series were based on successful novels, while others were created for television: Naked City; M-Squad; Perry Mason; Highway Patrol; Peter Gunn, Mr. Lucky; The Untouchables; the noirish Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour; Mike Hammer, Private Eye; Philip Marlowe, Private Eye; and Richard Diamond, Private Detective.

Then there were remakes of classic films such as High Sierra, filmed as I Died A Thousand Times (1955), and The Killers (1964), featuring Ronald Reagan as a most formidable villain.

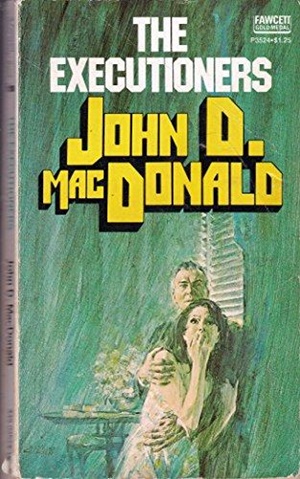

In 1960 Alfred Hitchcock gave us Psycho, a very influential, noirish-style psychological thriller based on the novel by Robert Bloch; (the screenplay was written by Joseph Stefano, the creator of the original The Outer Limits.) In 1962 we were treated to the first version of Cape Fear, which was adapted from John D. MacDonald’s novel, The Executioners.

In 1969 Raymond Chandler’s Little Sister was filmed as Marlowe, starring James Garner. 1969 also gave us the multi-Academy Award winning film version of Horace McCoy’s 1935 novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Elliott Gould played Philip Marlowe in 1973’s The Long Goodbye, based on the novel by Raymond Chandler; Leigh Brackett wrote the screenplay and changed the story’s timeline from 1949/1950 to the 1970s.

In 1969 Raymond Chandler’s Little Sister was filmed as Marlowe, starring James Garner. 1969 also gave us the multi-Academy Award winning film version of Horace McCoy’s 1935 novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Elliott Gould played Philip Marlowe in 1973’s The Long Goodbye, based on the novel by Raymond Chandler; Leigh Brackett wrote the screenplay and changed the story’s timeline from 1949/1950 to the 1970s.

Most notable was the excellent reboot of Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely, filmed in 1975 under its original title, and starring Robert Mitchum. 1975 also gave us The Black Bird, a spoof of and sequel to The Maltese Falcon starring George Segal as Sam Spade, Jr; Elisha Cook and Lee Patrick reprised their 1941 film roles.

The great Jim Thompson’s novel, The Killer Inside Me, made it to the big screen in 1976, and a remake of Chandler’s The Big Sleep followed in 1978, again starring Mitchum.

Hard-boiled crime and pulp fiction film noir continues to this day. Some personal favorite and notable films are: 1982’s noirish Blade Runner, based on Philip K. Dick’s classic science fiction novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Another film based on a novel by Jim Thompson, The Grifters, appeared in 1990, and in 1995 Walter Mosley’s breakthrough novel, Devil in a Blue Dress, made it to the silver screen.

One of the best of modern-day film noir is L.A. Confidential (1997), based on James Ellroy’s huge and complex novel. 2001 gave us the noirish Sin City, taken from Frank Miller’s graphic novel. In 2006 another of James Ellroy’s novels, The Black Dahlia, made its way into theaters, and in 2010 Martin Scorcese gave us Shutter Island, based on the novel by Dennis Lehane.

There have been other attempts at film noir in the past eight years, such as Drive (2011), adapted from James Sallis’ 2005 novel, and Nocturnal Animals (2016), based on Austin Wright’s 1993 novel, Tony and Susan. But for me, the era of great film noir has long since passed.

I’ve barely touched the surface here of classic novels and films, and clearly there are many writers, novels and movies I’ve failed to mention. But this article has already gone on longer than I had originally planned! I would love to see someone write about the film noir of Great Britain and other countries. Any takers?

I’d like to close with a special thank you to Bob Byrne, a regular contributor to Black Gate, who invited me to take part in this exploration of hard-boiled pulp fiction and film noir. Now go and read some of these stories and novels, go check out some of the films I’ve mentioned, and do remember to keep the getaway car’s engine running.

Please visit my Amazon Author’s page.

Please visit our blogsite, A Small Gang of Writers:

Thank you for your time, patience and interest.

Previous entries in the series:

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘Yellow Peril in the Pulps’ (Next Week)

Joe Bonadonna is the creator of Dorgo the Dowser and among other writings, can be found in Janet & Chris Morris’ long-running ‘…In Hell’ series. He’s also a very entertaining Facebook poster! Swing by his blogsite, A Small Gang of Writers:

Bob Byrne’s A (Black) Gat in the Hand appears weekly every Monday morning at Black Gate (until they finally get around to changing the password!).

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March 2014 through March 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!). He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

Though I know it’s completely unfilmable (Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler knew it too) and Double Indemnity is one of the greatest Noir films, I hate to lose Cain’s incredible, operatic ending, where Neff and Phyllis escape on a cruise ship and commit suicide together by jumping to the sharks. Its audacity blows me away every time I reread it.

Thomas Parker — I know. In those days, things had to have different endings in films. Nowadays, the ending my be more true to the novel.

I think that Jim Thompson was an amazing writer. But his stuff was so overwhelmingly bleak and depressing, I haven’t read anything by him in well over a decade.

But I remember watching Billy Zane and Gina Gershon in ‘This World, Then the Fireworks,’ which is based on a Thompson short story.

Boy – you want to talk about dark noir!!!