A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

I reached out to some friends to help me with A (Black) Gat in the Hand, as I certainly can’t cover everything and do it all justice. Our latest guest is author and fellow Black Gater, Joe Bonadonna. And Joe delivered an in-depth look at hardboiled adaptations on the silver screen. In fact, he covered so much ground, it’s gonna be a two-parter! So, let’s dig in!

Hardboiled Film Noir: From Printed Page to Moving Pictures (Part One)

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” — Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

Prologue

Crime does not discriminate. From city streets and slums to quiet suburbia, from the mansions of the rich to the boardrooms of the powerful, crime is alive and well. It can be found in dance halls, beer halls and gambling halls . . . speakeasies, seedy gin joints, smoke-filled pool halls, dive hotels, and wharf-side saloons. Crime exists everywhere, and writers and filmmakers have been telling stories about crime since Gutenberg invented the printing press.

Crime does not discriminate. From city streets and slums to quiet suburbia, from the mansions of the rich to the boardrooms of the powerful, crime is alive and well. It can be found in dance halls, beer halls and gambling halls . . . speakeasies, seedy gin joints, smoke-filled pool halls, dive hotels, and wharf-side saloons. Crime exists everywhere, and writers and filmmakers have been telling stories about crime since Gutenberg invented the printing press.

This article deals mainly with American pulp fiction, novels and films, and a few theatrical plays, too. I’m going to give a little background history on the source material for these films and on some of the writers who penned the original stories upon which they were based.

Long ago, long before television came along, the film industry turned to books, magazine stories, theatrical plays, and radio shows for their source material, as well as original screenplays. Movie moguls bought the rights to numerous best-selling novels, mined the pages of pulp magazines, comic books, and even newspaper comic strips.

Many films made during this period were Saturday matinee serials such as Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel, and The Shadow. Dick Tracy was actually given a series of stand-alone films, and of course we had Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan.

Most of these serials were the “comic book” films about pulp fiction superheroes, caped crusaders, masked avengers, and magical crime fighters. Many others films, however, were turned into “programmers,” as they were sometimes called: B-pictures with low budgets, made by up-and-coming directors, and featuring actors who had not yet attained A-list status.

These were movies that appeared as the first attraction on a double-feature billing and were more often geared towards adult audiences. There were also many films given the A-list treatment, with big budgets and top stars, writers, producers, and directors.

In no way is this article intended to be a definitive history of the pulp fiction gangster, detective, and film noir stories. That would be a daunting and exhausting task. What I hope to do is showcase certain pivotal and important films, and how they were based on the works of authors who wrote for such pulp publications as Argosy, All Detective, Battle Birds, Daredevil Aces, Dime Mystery, Spicy Mystery Stories, Gangland Detective Stories, and of course Black Mask.

While the silent film era produced its share of gangster and detective films, such as The Black Hand (1906) and Lon Chaney’s Outside the Law (1920), it wasn’t until 1929-1930 and the coming of “talking pictures” that the gangster film craze hit audiences like a right-cross, followed by the knock-out punch of film noir. But I’m not just discussing films here. What I want to point out is that all the films I mention were based on novels, short stories and in some cases, theatrical plays.

Today, Hollywood turns mostly to comic books and graphic novels, TV shows, reboots, and the occasional hot-selling novel to undergo a cinematic makeover. Be that as it may, let us not forget that Hollywood has always been in the business of sequels and remakes. Back in the days of Hollywood’s Golden Age, movie moguls often hired novelists, newspapermen, pulp magazine writers, and journalists of all kinds to adapt their own stories and articles into film scripts, and to write original screenplays, too. The films I mention here are only a small part of the films I’ve seen, and each one is based on a novel, short story or stage play.

Today, Hollywood turns mostly to comic books and graphic novels, TV shows, reboots, and the occasional hot-selling novel to undergo a cinematic makeover. Be that as it may, let us not forget that Hollywood has always been in the business of sequels and remakes. Back in the days of Hollywood’s Golden Age, movie moguls often hired novelists, newspapermen, pulp magazine writers, and journalists of all kinds to adapt their own stories and articles into film scripts, and to write original screenplays, too. The films I mention here are only a small part of the films I’ve seen, and each one is based on a novel, short story or stage play.

The 1930s

When I was a kid in the 1950s and 1960s, I fell in love with gangster films, especially those produced by Warner Brothers. Their films had a gritty, tough realism to them. The black and white cinematography, the huge, impressive back-lot sets, the dialogue and attitudes of the characters—all reflected the times: Depression Era America.

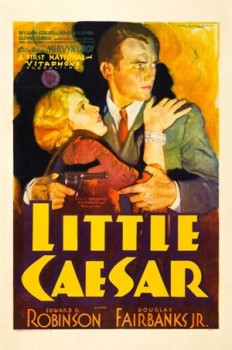

Films starring Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and George Raft were tough, hard-hitting films, and those actors quickly became my cinematic heroes. Some popular films of 1931 were Little Caesar, from the novel by William F. Burnett, and Public Enemy, based on an unpublished novel, Beer and Blood, by two former street thugs from Chicago, John Bright and Kubec Glasmon.

1932 gave us the original Scarface, taken from Armitage Trail’s 1929 novel. Crime dramas also made it to the Broadway stage and then later found their way to Hollywood: Dead End (1937) for example, was adapted from the play by Sidney Kingsley. Angels with Dirty Faces, from 1938, was based on a story by Rowland Brown. 1939 brought us such classics as: Each Dawn I Die, based on Jerome Odium’s novel, and The Roaring 20s, adapted from Mark Hellinger’s novel, The World Moves On.

There were scores of other gangster films in the 1930s; some were great, others not so good. Plus we had a slew of detective films, too, such as Brett Halliday’s Michael Shayne, based on his novels; all told, there were 77 novels and 300 short stories written between 1939 and 1958; many of them written by ghost writers or “diverse hands.” 1939 also gave us the Nick Carter, Master Detective films that originated in Ferrin Fraser’s stories, which were first published in Street & Smith’s dime novels and pulp magazines, and later became a hit radio drama.

The Mr. Moto novels of John Phillips Marquand became a popular film series, starring Peter Lorre in the lead role. Eight films were released between 1937 and 1939. Boris Karloff took the lead role as detective Mister Wong, based on Hugh Wiley’s novels (who wrote mostly for Collier’s Magazine.) Between 1938 and 1940 Karloff appeared in five films. (Oddly enough, in 1940, Charlie Chan’s #1 son, actor Keye Luke, played Wong in one feature film.)

S.S. Van Dine wrote twelve novels starring Philo Vance. Actor William Powell (who later appeared in six Thin Man movies) played Vance in three films between 1929 and 1930. Basil Rathbone also played Vance in one film in 1930; in 1933 Powell returned to the role for his fourth and final time. Warren William, who would later play Earl Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason in three of five films, also played Vance.

Author Damon Runyon, who wrote from 1911 until his death in 1946, was very popular in the 1930s, and many of his plays, novels and stories were turned into such films as A Slight Case of Murder, Little Miss Marker, Lady for a Day (based on his Madame La Gimp), and of course, Guys and Dolls. He romanticized and sentimentalized gangsters, and is responsible for introducing underworld terms and “nicknames” into our vocabulary, such as: roscoe, (gun); pineapple (hand grenade), and shiv (knife.)

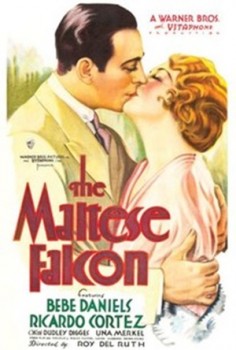

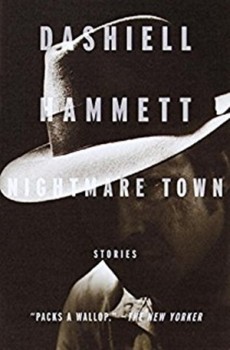

Dashiell Hammett became even more popular when Hollywood turned two of his novels into films—and one into a successful and long-running series. The Thin Man became a big hit and gave birth to a six-film series between 1934 and 1947; Hammett also wrote the original screenplay for 1936’s After the Thin Man. His 1929 novel, Red Harvest, was adapted for the 1930 film, Roadhouse Nights. Probably his most famous novel, The Maltese Falcon, was filmed twice in the 1930s. First came Dangerous Female (1931), with Ricardo Cortez playing Sam Spade, a film which pretty much sank like a corpse weighted down with chains and dumped in a river.

Dashiell Hammett became even more popular when Hollywood turned two of his novels into films—and one into a successful and long-running series. The Thin Man became a big hit and gave birth to a six-film series between 1934 and 1947; Hammett also wrote the original screenplay for 1936’s After the Thin Man. His 1929 novel, Red Harvest, was adapted for the 1930 film, Roadhouse Nights. Probably his most famous novel, The Maltese Falcon, was filmed twice in the 1930s. First came Dangerous Female (1931), with Ricardo Cortez playing Sam Spade, a film which pretty much sank like a corpse weighted down with chains and dumped in a river.

Later, in 1936, The Maltese Falcon was turned into a vehicle for Bette Davis titled Satan Met a Lady, a mystery-comedy along the lines of The Thin Man. There was no Sam Spade or Brigid O’Shaughnessy in this one, and most of the other character names had been changed, too. Davis played Valerie Purvis, and Warren William played a lawyer named Ted Shane. This film version was about as popular as a raid on a speakeasy. Hammett’s The Glass Key was first filmed in 1935, starring George Raft. In 1939 it was turned into a radio drama for Orson Welles’ CBS radio program, The Campbell Playhouse.

There was also Sapper’s (H.C. McNeil) Bulldog Drummond, and Jack Boyle’s Boston Blackie. These were a modestly-budgeted yet popular series of films, and both started out in the silent era. And then there were the classic Charlie Chan films of the 1930s and 1940s, based on the six novels written by Earl Derr Biggers between 1925 and 1932.

Numerous films starring the Oriental detective were produced during the years 1926 to 1949; there were also two television films made in 1973 and 1981, and even a Mexican version, released in 1955. Among the many actors to portray Chan, the two most famous were Warner Oland and Sidney Toler. Oland appeared in sixteen films between 1931 and 1937, while Toler appeared in 22 films between 1939 and 1946.

Leigh Brackett is certainly no stranger to the readers of Black Gate and anyone who loves science fiction; she was often referred to as the Queen of Space Opera. Brackett was also a screenwriter well known for her work on such films as Hold Back the Dawn (1941), The Big Sleep (1946), Rio Bravo (1959), The Long Goodbye (1973) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Her only novel given the celluloid treatment was The Tiger Among Us (1957), filmed as 13 West Street in 1962. Another crime novel of hers, An Eye for an Eye (1957) was adapted for television as a Suspicion series episode in 1958.

It’s a shame that more of her novels and stories didn’t make it to the big screen because Brackett wrote some great hardboiled stories, as well as a library’s worth of science fiction. Her 1944 crime novel, No Good from a Corpse, would have made a terrific film. She was the first woman shortlisted for the Hugo Award.

The 1940s

During the Depression Era of the 1930s, gangster films dealt mostly with bootlegging, bullets and blood, cops and robbers, city politics and territorial gangland wars. But as the decade drew to a close, these films began to change, began to evolve. While the detective films of the 1930s dealt with themes such as blackmail, and murder in dark alleys and high society, new elements became staples of what would later be dubbed film noir . . . “dark cinema,” first coined by French film critic Nino Franks in 1946.

Drugs, espionage, infidelity, childhood abuse and trauma, and other psychological issues were just a few of the more adult themes to enter the world of cinematic crime. According to Wikipedia,

“Hollywood’s classical film noir period is generally regarded as extending from the early 1940s to the late 1950s. Film noir of this era is associated with a low-key, black-and-white visual style that has roots in German Expressionist cinematography. Many of the prototypical stories and much of the attitude of classic noir derive from the hardboiled school of crime fiction that emerged in the United States during the Great Depression.”

All that being said, let’s move on.

Just as the 1930s was the decade of the gangster film, the 1940s was the decade of film noir. By this time, however, the traditional, 1930s-type of gangster film had begun its decline in popularity. With Prohibition long repealed, the Depression at an end, and the shadow of a Second World War spreading across Europe, audiences had other concerns, and tastes and attitudes had changed. Something new crept into crime movies like a killer emerging from the shadows of a dead-end street.

Just as the 1930s was the decade of the gangster film, the 1940s was the decade of film noir. By this time, however, the traditional, 1930s-type of gangster film had begun its decline in popularity. With Prohibition long repealed, the Depression at an end, and the shadow of a Second World War spreading across Europe, audiences had other concerns, and tastes and attitudes had changed. Something new crept into crime movies like a killer emerging from the shadows of a dead-end street.

Plots were no longer simple and straight forward in terms of heroes versus villains: there were now shades of gray where the good guys were a bit tarnished and the bad guys a lot more polished and sophisticated.

Besides Dashiell Hammett and Earle Stanley Gardner, other members of the Black Mask gang of writers soon found their stories and characters illuminated on the big screen: writers such as Raymond Chandler, Paul Cain and the wonderful Cornell Woolrich, who was rated the fourth best crime writer of his day, behind Hammett, Gardner and Chandler.

More film noir screenplays were based on works by Woolrich than any other crime novelist, and many of his stories were adapted during the 1940s for Suspense and other dramatic radio programs. He wrote under his own name as well as the pen names William Irish and George Hopley. Some of his novels turned into films are: Phantom Lady (1944), Black Angel (1946), The Leopard Man (1946), and Alfred Hitchcock’s classic Rear Window (1954), based on Woolrich’s novel, It Had to Be Murder.

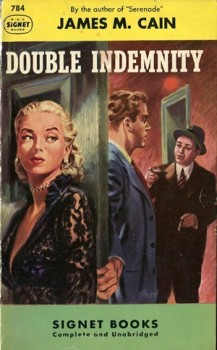

James M. Cain was a best-selling author who saw many of his published novels turned into films. Perhaps his most famous novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, was filmed twice, in 1946 and again in 1981. Besides his brilliant novel, Double Indemnity, Cain also wrote the classic, lurid novel, Mildred Pierce, which was filmed in 1945. Cain spent many years in Hollywood working on screenplays, but his name appears as a screenwriter in the credits of only two films: Stand Up and Fight (1939) and Gypsy Wildcat (1944), for which he is one of three credited screenwriters.

For Algiers (1938) Cain received a credit for “additional dialogue.” Out of the Past (1947), directed by Jacques Tourneur, was based on the Daniel Mainwaring (writing as Geoffrey Homes) novel Build My Gallows High. The script was written by Mainwaring, with uncredited revisions from Cain and Frank Fenton.

Dashiell Hammett, who began writing in 1923 and attained even greater fame and popularity in the 1930s, was still a force to be reckoned with in the 1940s. He wrote the original screenplay for Shadow of the Thin Man in 1941, as well as the screenplay for 1943’s Watch on the Rhine, based on Lillian Hellman’s play. He left school when he was 13 years old and held several jobs before working for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He served as an operative for Pinkerton’s between 1915 and 1922, with time off to serve in World War I. His experiences as an operative no doubt inspired his Continental Op, as well as his other characters.

Dashiell Hammett, who began writing in 1923 and attained even greater fame and popularity in the 1930s, was still a force to be reckoned with in the 1940s. He wrote the original screenplay for Shadow of the Thin Man in 1941, as well as the screenplay for 1943’s Watch on the Rhine, based on Lillian Hellman’s play. He left school when he was 13 years old and held several jobs before working for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He served as an operative for Pinkerton’s between 1915 and 1922, with time off to serve in World War I. His experiences as an operative no doubt inspired his Continental Op, as well as his other characters.

1942 saw the second film version of his novel, The Glass Key, this one starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake. In 1949 The Glass Key was once again produced, this time for television as part of The Westinghouse Studio One series. But undoubtedly the biggest hit and one of the most popular characters is Hammett’s Sam Spade. In 1941 John Huston not only wrote the screenplay but made his directorial debut with the third and by far the best film version of The Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade. Except for the fact that in the novel Gutman has a daughter who lures Spade up to her father’s room but doesn’t appear in Huston’s film, this is the most faithful to the novel film version to date.

The Maltese Falcon is the film that pretty much inspired all the films and a whole new genre that was soon to follow. And by the way, while many actors have portrayed Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, only Humphrey Bogart has the distinction to having played both Spade and Marlowe.

And that brings us to the end of part one. Since we finished with Hammett, we’ll start up part two with Raymond Chandler. Tune in next week!

Previous entries in the series:

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (next week)

Joe Bonadonna is the creator of Dorgo the Dowser and among other writings, can be found in Janet & Chris Morris’ long-running ‘…In Hell’ series. He’s also a very entertaining Facebook poster! Swing by his blogsite, A Small Gang of Writers:

Bob Byrne’s A (Black) Gat in the Hand appears weekly every Monday morning at Black Gate (until they finally get around to changing the password!).

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March 2014 through March 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!). He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

Thank you, Bob, for this grand opportunity to flex my cinematic and literary muscles, and for letting me stretch quite a bit.