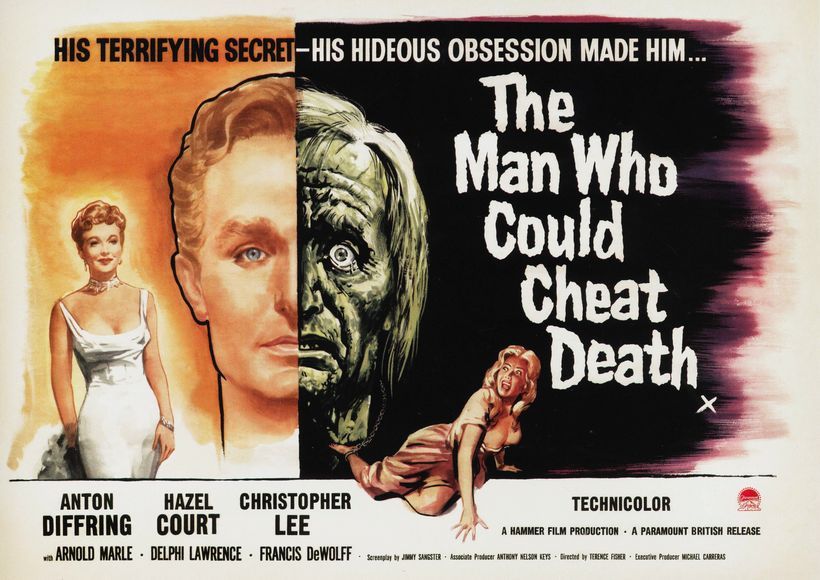

October Is Hammer Country: The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959)

The Man Who Could Cheat Death arrived during the fast and thrilling early days of Hammer Horror. The studio was tearing through Gothic hits from director Terence Fisher and the talented crew at the Bray soundstages: The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Dracula, The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Hound of the Baskervilles, The Mummy (1959), The Brides of Dracula, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (1960). Looking at that line-up, it’s obvious why The Man Who Could Cheat Death hasn’t made much of a lasting impression. Where’s the marquee value character or monster? Also, where’s Peter Cushing, Hammer’s headliner? He’s in all these movies except The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll … and The Man Who Could Cheat Death.

This odd-movie-out of early Hammer came about because of a production deal with Paramount. Once Hammer scored huge international hits with Frankenstein and Dracula films, the major Hollywood studios were eager to make co-financing deals and offer up their best horror properties for the Hammer treatment. But Paramount didn’t have a large catalogue of horror movies like Universal did. What they gave Hammer was a little-known 1944 film, The Man in Half Moon Street, which was an adaptation of a 1939 play by Alfred Edgar under the obvious pseudonym Barré Lyndon. The material was ghoulish enough for Hammer’s purposes: a mad-scientist tale with a touch of The Picture of Dorian Grey. Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster switched the story to Paris in 1890 to fit the studio’s Gothic style. Production was ready to roll with Fisher directing, Peter Cushing in the lead, and Christopher Lee as the main supporting part.

Except for the lack of a big name horror property, everything looked promising. Then, just before filming started, Cushing backed out of the production, claiming exhaustion after the barrage of movies he’d just done for the studio. Hammer quickly cast German actor Anton Diffring in the lead, probably because Diffring had played the part in a recent television version of The Man in Half Moon Street. He’d already replaced Cushing once before when he took over as Baron Frankenstein in a TV pilot Hammer produced for Columbia, Tales of Frankenstein. (The show didn’t go to series.)

Looking back from a contemporary perspective, It seems bizarre Hammer passed over raising Christopher Lee from the supporting cast and into the title part when Cushing left. Lee would’ve been phenomenal as the mad scientist/tortured artist who justifies murder to keep himself looking younger. But the Hammer brass didn’t yet see Lee as a headliner, even though he’d played Dracula, the Frankenstein Monster, and the Mummy. It’s difficult to watch the film today and not imagine what might have been if either Cushing or Lee had played Dr. Bonnet, rather than Diffring.

The setting is a Hammerized version of Paris, which seems inhabited solely by Londoners and Germans. Georges Bonnet, a renowned doctor who has a hobby of sculpting beautiful women, has run into a bit of a bind. He’s actually a hundred and four years old and has kept himself young through a breakthrough glandular operation. The operation must be renewed every ten years, or Bonnet’s stolen years will catch up with him. However, the doctor’s long-time partner in the experiments, Prof. Ludwig Weiss (Arnold Marlé, who played the same part in the TV version with Diffring), has chosen to age naturally and a recent stroke has made it impossible for him to perform the operation. With only days before Bonnet’s time is up, he tries to convince another doctor, Pierre Gerard (Lee) to do the operation. Making the situation trickier is that Bonnet and Gerard are both in love with the same woman, Bonnet’s model Janine Dubois (Hazel Court). Bonnet is also murdering people to get fresh glands, so there’s a police investigation poking around.

The resulting film is one of the most sedate Terence Fisher made. The stage play origins of The Man Who Could Cheat Death are often too clear, with lengthy dialogue scenes and the restriction to a handful of interior sets. The horror premise could sustain an urbane 1940s Paramount picture, but there’s not sufficient terror for the new era of Hammer shocks. When Terence Fisher had just turned Universal’s slow-moving Kharis mummy into a killing machine smashing open doors and hurling people across desks, it’s not enough to have Anton Diffring give a few people acid burns (for some reason Bonnet develops acid hands when he’s on the edge of dying) and kill a few women off-screen. Even the fiery finale, a Hallmark of Fisher’s horror films, is short and rushed.

Diffring isn’t terrible in the role. He has an intense presence and provides madman energy to the many talky scenes. Diffring had carved out a niche in British cinema playing Nazi officers in World War II pictures. His intense blue eyes and square Teutonic features made him a natural for these parts, although Diffring must have felt weird about this since he was a refugee from the Nazis in the 1930s because he was gay and half Jewish. But despite having the gusto to tackle the mad scientist and tortured artist part of the character of Dr. Bonnet, Diffring fails to give the character some amount of empathy. This empathy is the crucial element both Cushing and Lee brought to their horror parts. Diffring is too theatrical and often seems unaware of the actors playing across from him. The performance is an enjoyable sort of ham, but Diffring doesn’t go deeper into what drives Georges Bonnet aside from a passion not to die horribly.

Low-empathy troubles the entire movie, since it’s difficult to sympathize with any of the three leads. Hazel Court does what she can with Janine, but the character is a superficial aristocrat and not much more, and Diffring doesn’t stir up much chemistry with her. Lee is imposing as Dr. Gerard, but also far too icy; Gerard is speciously the hero — the character responsible for bringing an end to the story — but it’s difficult to care about him rescuing Janine from Bonnet when those two narcissists really deserve each other.

The only character who gives the audience something to hold onto is the elderly Prof. Weiss, who’s come to understand the evil that Bonnet is perpetrating and wants his life to end as it should’ve long ago. Although Arnold Marlé and Anton Diffring often get trapped in long conversation scenes — their first one runs eight minutes, which is a lot of German accent to absorb in a British movie set in France. But these are the most interesting scenes in the film because they develop the theme of the importance of aging as part of life. Bonnet’s experiment caused him to lose his way, and he grips onto youth so hard that his humanity has collapsed. This contrasts well with Weiss, who chose not to benefit from the experiment. Marlé creates the moral center of the story, something it needs, but … look, I’m still imagining what these scenes would’ve been like with Cushing or Lee arguing against Marlé, and the picture is a better movie. Still a slow one, but with more depth.

On the technical side, The Man Who Could Cheat Death is the first solo makeup credit for Roy Ashton, who had worked as Phil Leakey’s assistant on previous Hammer Gothics and would create the impressive makeup designs for The Mummy, The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), The Phantom of the Opera (1963), She (1965), and The Reptile (1966). A film like The Man Who Could Cheat Death is building up to the “Dorian Grey” moment when age catches up with its protagonist, and the decrepit change Ashton works onto Anton Diffring is impressive. But it only appears on screen briefly as Bonnet’s laboratory goes up in flames in the finale.

The rest of the Hammer crew is up to their usual Golden Age high standards. Few Hammer movies show off so well why Terence Fisher loved working with production designer Bernard Robinson: anywhere the camera points, it gets a lensful of great imagery. Although limited to a handful of sets — a series of rich Parisian apartments — the visual details lavished on everything creates the sumptuous Hammer atmosphere even if the story isn’t as up to the task.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death is available in a Region A (North America) Blu-ray from Kino Lorber, which includes a commentary from Troy Howarth and interviews with Hammer experts Kim Newman and Jonathan Rigby.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

I saw this, at age 8 1/2, at the drive-in not long after its release (my parents rarely took me and my two sisters to horror or science fiction films; they literally gave me nightmares); there must have been a Doris Day/Rock Hudson romcom on with it, or a WW II film, or a Western, or we’d never have gone. I hadn’t seen it in nearly 60 years when I purchased a Blu-ray last year. I’d remembered it fairly well, especially the ending. Mr. Harvey’s assessment here is accurate; not the greatest film, but not the worst. And after having seen Peter Cushing & Christopher Lee in lots of such films, I cannot imagine anyone else but but Anton Diffring in the title role. Thanks for bringing this one up!

I haven’t seen the movie, but I have a lot of sympathy for Anton Diffring, surely one of the most typecast actors there has ever been.