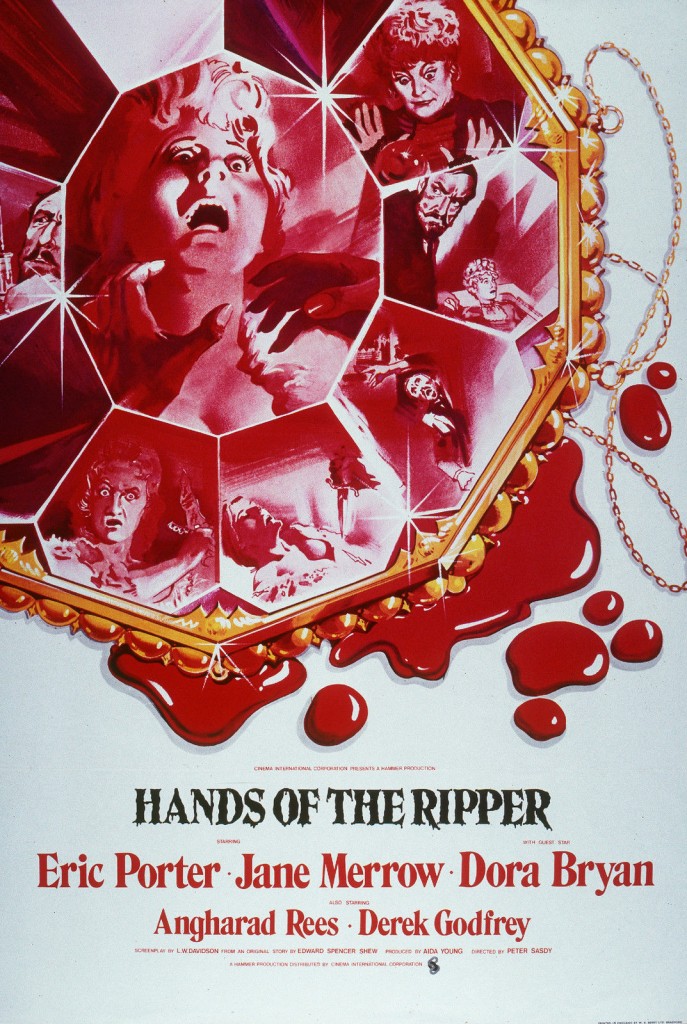

October Is Hammer Country: Hands of the Ripper (1971)

“You can’t cure Jack the Ripper!”

“You can’t cure Jack the Ripper!”

Hammer Film Productions was a different place in the 1970s than in the 1950s and ‘60s. And although it was generally a less artistic place after in-house development stopped and the original producers left, it wasn’t an awful place. It’s similar to third season original Star Trek: more bad episodes than before, but what’s good is still damn good. You got “The Way to Eden,” but you also got “The Enterprise Incident.” With Hammer, you got the dreadful The Horror of Frankenstein, but you also got Hands of the Ripper — which, for my money, is Hammer’s best horror film of the decade. It was originally released on a double bill with Twins of Evil, making it the last great Hammer double feature.

Jack the Ripper has fueled many mystery and horror films. Hammer visited the topic in their pre-Gothic days in a 1950 period crime drama, Room to Let. It wasn’t until 1971 that the studio gave the Ripper the full horror treatment. Two treatments, in fact. Hands of the Ripper was shot at the same time as Doctor Jekyll and Sister Hyde, a sex-change twist on Stevenson’s novel set during the Whitechapel killings. Weird as the Sister Hyde idea may sound, it’s Hands of the Ripper that takes the dramatically more challenging and interesting approach to Jack the Ripper. Rather than set the story during the original killings in the late 1880s, the screenplay by L. W. Davidson (from an original story by Edward Spencer Shrew) shifts forward fifteen years to Jack the Ripper’s daughter, teasing a spirit possession story and giving the Ripper’s gory hands and misogynistic rage to a young woman.

Hands of the Ripper was shot at Pinewood Studios with Hungarian director Peter Sasdy in the director’s chair. Sasdy already had a history with Hammer. He directed the best of the Dracula sequels starring Christopher Lee, Taste the Blood of Dracula (1969); but in 1971 he was coming off Countess Dracula, a bizarrely boring movie based on the story of Countess Elizabeth Bathory. Re-teamed with producer Aida Young, who worked with him on Taste the Blood of Dracula, Peter Sasdy recovered and made one of his best movies. Young was one of the few women producers in England at the time, and her other Hammer films include Dracula Has Risen From the Grave and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth. Considering she produced Sasdy’s best films, the two must have shared a powerful creative partnership.

The film opens with a prologue in 1888 at the end of the Whitechapel killings. The Ripper, dressed in the top hat-and-tails getup that’s become his standard modern image, stabs his wife to death before the eyes of his young daughter Anna. A match cut moves to 1903, where Anna (Angharad Rees) is now a withdrawn young woman who’s either suffering from the trauma of seeing her mother’s killing or is occasionally possessed by the murderous spirit of her father. Whatever the source, flickering reflections put Anna into a trance state that can quickly escalates to making her a brutal killer.

Dr. Pritchard (Eric Porter), a psychoanalyst devoted to the theories of Freud, takes custody of Anna to discover the cause of her psychosis. He’s convinced she may lead to a discovery of a secret about the human psyche and the effects of trauma. To make progress, he’s willing to cover up the bodies Anna leaves behind when her trance/possession is triggered.

Although it contains a number of gory shock moments (there’s queasy one involving hat pins), Hands of the Ripper is, at heart, a sentimental tragedy. It stands out from Hammer’s more operatic features as an intimate chamber piece with occasional gouts of blood. I could imagine a stage play fashioned from the material. Sasdy directs with great pacing and plenty of superb visuals, but its the lead performances from Porter and Rees that propel it to minor classic status.

Eric Porter was a popular BBC actor who had appeared in one previous Hammer film, The Lost Continent (1968). The character of Dr. Pritchard is a part that seems suited to Christopher Lee, but Lee may have come across as too sinister. Porter balances his portrayal carefully along the border of what an audience can sympathize with. Dr. Pritchard wants to protect Anna, but he’s also using her and knows she’s a danger to others. It becomes gradually evident his feelings toward Anna aren’t completely fatherly, but romantic/sexual. This is where Porter does the most remarkable acting, because Pritchard doesn’t come across as overtly sleazy or manipulative at the start: his attraction to Anna seems to dawn naturally until it crosses the point where — well, where it has consequences.

Porter’s acting bolsters a subplot about Pritchard’s son Michael (Keith Bell) and his engagement to Laura (Jane Merrow), a blind woman. Pritchard isn’t happy about the arrangement, but it’s never clear why. Nor does it need to be; simply the way Porter gruffly deals with Michael and Jane while attending to Anna reinforces the main storyline — and we need to have Laura around for a tense finale, because why else have a blind woman in a horror film?

This was an early role for Angharad Rees, who had a long career in television and stage. She’s the heart of the movie: if the audience doesn’t see her as a victim, even after watching her violently murder women, the story will flatline. Rees plays Anna as bright and innocent, but also damaged. We understand why Pritchard wants to protect her, but our sympathies eventually extend to wanting to protect Anna from Pritchard. We only see Rees go into the Ripper-fury for short bursts, but she’s truly terrifying in these moments. She then shifts back to the damaged creature who stands shivering with blood coating her hands. Rees sells the tragedy of Anna and the tragedy of the movie.

Credit to Sasdy for using visuals to implicate the Ripper in the killings, such as showing his diseased and scarred hands reaching for the instruments of death rather than Anna’s. This trick helps distance Anna from responsibility in the audience’s eyes. The movie also raises the tantalizing question of the nature of Anna’s affliction. Is her father’s spirit possessing her? Or has she inherited a mental illness from him? The movie only commits to one moment of supernatural certainty, which is when a spiritual medium sees into Anna’s past to identify her father as the Ripper. But this might be an isolated incident, not a confirmation of possession. Pritchard fights to proclaim Anna’s trances are purely based on psychological damage, and they very well could be. It’s hard to say which possibility — possession or madness — is more frightening.

If Anna actually is possessed by her dead father, it creates an intriguing sexual angle. Anna only turns murderous in her trances when someone shows affection toward her, such as a kiss. This is superficially similar to Cat People (1942). But in Cat People, the idea is feminine sexuality turns dangerous when woken. In Hands of the Ripper, it’s a male persona that takes over and does the killing — the Ripper acting out his hatred of female sexuality that originally drove him to murder prostitutes. There’s a subtle play of possibilities at work that makes the film one of the most interesting variations of the “female slasher.”

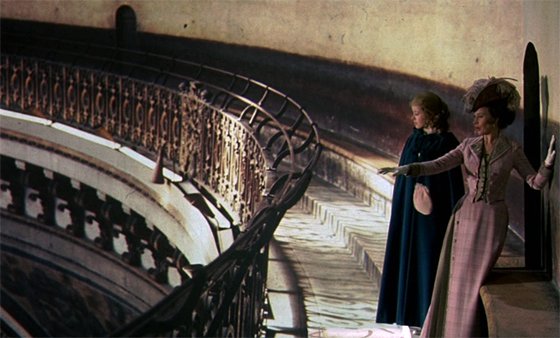

Thanks to access to sets built for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1969) on the Pinewood backlot, Hands of the Ripper looks more expensive than other early ‘70s Hammer horrors. Compared to Doctor Jekyll and Sister Hyde, which was shooting across town at Shepperton Studios on three tiny interior sets, Hands of the Ripper looks like a David Lean film. (As much as I get a kick out of the silliness of Doctor Jekyll and Sister Hyde, it fails to live up to the potential of its salacious concept.) Hands of the Ripper even manages to get away with using photographic tricks for its finale inside St. Paul’s Cathedral after the production was denied shooting permits at the actual location. Although it’s easy to tell where photographic plates are substituting for the inside of St. Paul’s dome, the climax still delivers. The score by Christopher Gunning, centered on a sweet and lush theme for Anna, helps the movie feel like a glossy BBC production. That’s an impressive feat for a film that also has a scene of a woman stabbed through the neck with a shattered hand mirror.

Hands of the Ripper is available in Region A (North America) on a Blu-ray from Synapse. The disc features a documentary on the film with interviews with Peter Sasdy and actress Jane Merrow.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.