Under a Blood-Red Sun: The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe

Of those values that Master Malrubius (who had been master of apprentices when I was a boy) had tried to teach me, and that Master Palaemon still tried to impart, I accepted only one: loyalty to the guild. In that I was quite correct — it was, as I sensed, perfectly feasible for me to serve Vodalus and remain a torturer. It was in this fashion that I began the long journey by which I have backed into the throne.

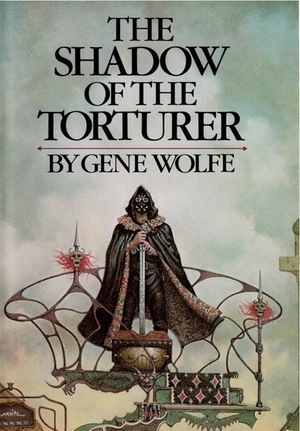

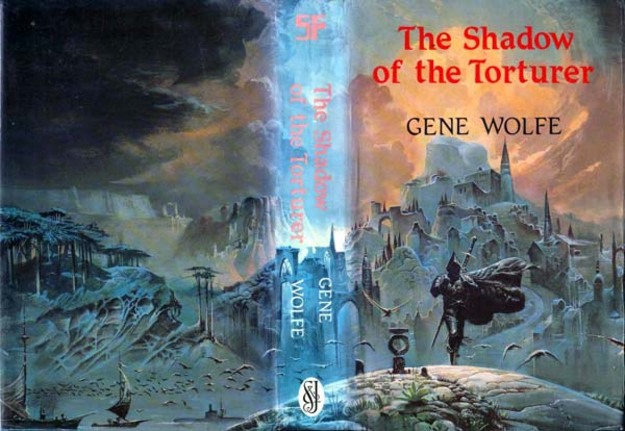

Based solely on Don Maitz’s now classic cover art, I grabbed Gene Wolfe’s The Shadow of the Torturer (1980) from the library shelf as soon as I laid eyes on it. I cracked it open and dropped it almost at once. It was too dense and too alien for my teenaged brain to appreciate. To this day, Gene Wolfe, considered one of the most accomplished scifi/fantasy writers (see “Sci-fi’s Difficult Genius” by Peter Bebergal), remains a serious blind spot for me, even if I do have a large selection of his most important works gathering dust on the shelf.

Based solely on Don Maitz’s now classic cover art, I grabbed Gene Wolfe’s The Shadow of the Torturer (1980) from the library shelf as soon as I laid eyes on it. I cracked it open and dropped it almost at once. It was too dense and too alien for my teenaged brain to appreciate. To this day, Gene Wolfe, considered one of the most accomplished scifi/fantasy writers (see “Sci-fi’s Difficult Genius” by Peter Bebergal), remains a serious blind spot for me, even if I do have a large selection of his most important works gathering dust on the shelf.

I did finally revisit Shadow some years ago, but while I liked it and the next book in the sequence, The Claw of the Conciliator, I didn’t go on to read the remaining three volumes, The Sword of the Lictor, The Citadel of the Autarch, and The Urth of the New Sun. Well, it finally seems like the right time to give the series another go.

Urth is a dull, rusted-out world orbiting a fading, red sun. Within the Matachin Tower, in the citadel of the great capital city of Nessus, the Order of the Seekers for Truth and Penitence, or the Torturers, service the clients sent them by the Autarch, absolute ruler of the Commonwealth. Once among their members was a young apprentice named Severian. From some future vantage point Severian has set out to narrate the great story that seems to end with him upon a throne, presumably the Autarch’s.

From William Hope Hodgson to Clark Ashton Smith to Jack Vance, worn-out Earth with fading-ember sun has been explored many times. For Hodgson it was a stage on which to tell a story of romantic heroism, for Smith, to spin tales of decadence and terror, and for Vance, cynically comic tales of adventure. With only the first book read, it’s not clear where Wolfe is going with this series. The myths and legends that are told by various characters throughout The Shadow of the Torturer are filled with angels and demons and premonitions of impending apocalypse. While there are elements similar to those in the works of the illustrious earlier sojourners to Earth’s dying days, Wolfe seems to be aiming for something deeper and more complex than his forebears.

Severian’s Urth is decrepit and weather-beaten. More knowledge seems to have been forgotten than is still remembered and the world staggers along, propped up more by tradition than by any real understanding or philosophy. While we learn man has traveled to the stars, that seems to be long in the past. The tower used by the Torturers, as well as those of several other guilds, are clearly long-immobilized rocket ships. The sand favored by many artists for their creations is atomized glass of long-vanished cities. What appears to Severian as a painting of a warrior in a barren land, to the reader it is obviously Neil Armstrong on the moon.

As a torturer, Severian goes dressed in a cloak and hood of the guild’s color, fuligin; a shade of black darker than any other. No folds or wrinkles can be seen in it, instead, it looks like a rent in space. As an executioner, he carries a great mercury-filled sword called Terminus Est, translated roughly as “the line is drawn here”, on his back. He is a tall young man of many talents, most ones involving destroying or repairing the human body.

As a torturer, Severian goes dressed in a cloak and hood of the guild’s color, fuligin; a shade of black darker than any other. No folds or wrinkles can be seen in it, instead, it looks like a rent in space. As an executioner, he carries a great mercury-filled sword called Terminus Est, translated roughly as “the line is drawn here”, on his back. He is a tall young man of many talents, most ones involving destroying or repairing the human body.

Despite his grim trade, Severian is an enjoyably sardonic narrator. Without ever becoming as gleefully pessimistic as Jack Vance, Wolfe still imbues a certain degree of humor in The Shadow of the Torturer.

Those who have paid the carnifex to make the act a painless or a painful one may be likened to the literary traditions and accepted models to which I am compelled to bow. I recall that one winter day, when cold rain beat against the window of the room where he gave us our lessons, Master Malrubius — perhaps because he saw we were too dispirited for serious work, perhaps only because he was dispirited himself — told us of a certain Master Werenfrid of our guild who in olden times, being in grave need, accepted remuneration from the enemies of the condemned and from his friends as well; and who by stationing one party on the right of the block and the other on the left, by his great skill made it appear to each that the result was entirely satisfactory. In just this way, the contending parties of tradition pull at the writers of histories. Yes, even at autarchs. One desires ease; the other, richness of experience in the execution … of the writing. And I must try, in the dilemma of Master Werenfrid but lacking his abilities, to satisfy each. This I have attempted to do.

There remains the carnifex himself; I am he. It is not enough for him to earn praise from all. It is not enough, even, for him to perform his function in a way he knows to be entirely creditable and in keeping with the teaching of his masters and the ancient traditions. In addition to all this, if he is to feel full satisfaction at the moment when Time lifts his own severed head by the hair, he must add to the execution some feature however small that is entirely his own and that he will never repeat. Only thus can he feel himself a free artist.

The Torturers replenish their ranks with the male children of the pregnant prisoners sent to them. Severian, like all his guild brothers, was one such infant, and knows no other family or home but the guild. For him it is all, and when he commits a grievous offense against one of its primary rules he would almost rather be executed than merely banished.

That crime is compassion, perhaps the worst that any torturer could commit. A young man of little apparent empathy, a chain of circumstances leads him to form a bond with a high-born prisoner. Subjected to the revolutionary, a device that will lead her to slowly rip herself to pieces over several weeks, she turns to Severian for help and he accedes. He turns himself in and is banished to the hinterlands to serve out his days not as an exalted journeyman in the guild, but as a mere executioner in a frontier town.

Much of The Shadow of the Torturer concerns Severian’s journey from the Matachin Tower to the great gate in the wall surrounding Nessus. Along the way he acquires, loses, and reacquires companions. He gets challenged to a duel with poisonous flowers and nearly drowned in a lake in a mysterious botanical garden. Not quite the innocent abroad, nonetheless, his trek across the strange urban landscape of Nessus is a maturing experience for the young guildsman. When he and his new associates finally reach the far end of the gate, Severian promptly brings the book to a close:

Here I pause. If you wish to walk no farther with me, reader, I cannot blame you. It is no easy road.

Wolfe’s book has grabbed me completely. It may not be sui generis — it is indeed redolent of Smith and Vance, plus maybe a touch of Peake — but it might just be the apotheosis of the dying earth genre. He is exploring more than just decadence and decay in the setting of its creators.

The Shadow of the Torturer is dense with detail and atmosphere. Every scene, every character comes to life through Wolfe’s prose. Here is Severian describing one of the two Master Torturers:

The Shadow of the Torturer is dense with detail and atmosphere. Every scene, every character comes to life through Wolfe’s prose. Here is Severian describing one of the two Master Torturers:

Gurloes was one of the most complex men I have known, because he was a complex man trying to be simple. Not a simple, but a complex man’s idea of simplicity. Just as a courtier forms himself into something brilliant and involved, midway between a dancing master and a diplomacist, with a touch of assassin if needed, so Master Gurloes had shaped himself to be the dull creature a pursuivant or bailiff expected to see when he summoned the head of our guild, and that is the only thing a real torturer cannot be. The strain showed; though every part of Gurloes was as it should have been, none of the parts fit. He drank heavily and suffered from nightmares, but he had the nightmares when he had been drinking, as if the wine, instead of bolting the doors of his mind, threw them open and left him staggering about in the last hours of the night, trying to catch a glimpse of a sun that had not yet appeared, a sun that would banish the phantoms from his big cabin and permit him to dress and send the journeymen to their business. Sometimes he went to the top of our tower, above the guns, and waited there talking to himself, peering through glass said to be harder than flint for the first beams. He was the only one in our guild — Master Palaemon not excepted — who was unafraid of the energies there and the unseen mouths that spoke sometimes to human beings and sometimes to other mouths in other towers and keeps. He loved music, but he thumped the arm of his chair to it and tapped his foot, and did so most vigorously to the kind he liked best, whose rhythms were too subtle for any regular cadence. He ate too much and too seldom, read when he thought no one knew of it, and visited certain of our clients, including one on the third level, to talk of things none of us eavesdropping in the corridor outside could understand. His eyes were refulgent, brighter than any woman’s. He mispronounced quite common words: urticate, salpinx, bordereau. I cannot well tell you how bad he looked when I returned to the Citadel recently, how bad he looks now.

This book is by turns gripping and humorous. In the background a great rebellion against the Autarch seems to be stirring. It is from his unintentional involvement with its leader, Vodalus, that Severian’s path is laid. There is a mad carriage race and several duels alongside ridiculous con artists and villains with laughably irrational justifications for their crimes.

While The Shadow of the Torturer is presented as a bildungsroman, it is permeated with the aura of a myth being born. We know he is going to enthroned someday, so when it is intimated that his unknown parentage might be noble, it’s easy to believe. There’s an air of “chosen one” to Severian; stories, prophecies, and legends fill the air around him. The reader is constantly reminded the world is going to end, perhaps sooner than later. Whenever it occurs, one gets the feeling Severian will be at the heart of things.

Severian makes clear he is incapable of forgetting anything. That he is telling his story from the position of its conclusion, there should be no mysteries or secrets, and yet there are. It seems he’d be a truthful narrator, but it becomes evident several times he is not. Again, where Wolfe is going with this I am uncertain, but it’s certainly hooked me for the next book. I need to know what happens next.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about nothing in particular, but he might be writing about swords & sorcery again any day now (actually, I’m writing about Westerns right now).

I didn’t find these until I was in college, but I was hooked pretty much from page 1.

Glad you finally found your way! I was hooked at the age of 15 when I picked up “Shadow” in my high school library. I never had a problem with the prose, but I’d already read my way through a couple of dictionaries at that point. Never had a problem with CAS at almost the exact same age.

Neither Wolfe nor Smith are for everyone, but I consider both of them among the greatest writers in literature. I recommend Wolfe’s “Soldier” and “Whorl” series as well.

I read the initial four in a rush, almost thirty years ago. (I never did get around to Urth, though.) I was amazed and enthralled, all the while realizing that these were dense, complex books that needed a more careful reading than I was giving them. I’ve long intended to revisit them, and this may be the spur.

@Joe H – As was I. Great, wonderful book

@Deuce – CAS I always appreciated. Perhaps his almost playful cynicism and decadence was more readily appreciated by teenaged me. I plan on reading the Soldier books in the near future.

@Thomas P. – I suspect that’s how they should be read. When I didn’t jump right to the 3rd book, when I picked it up several months later I knew I’d have to start over with SHADOW and I just wasn’t up for that.

I’m totally stealing this, but I’ve heard that the best way to read Wolfe’s books is to read them at least twice.

I have to admit that I didn’t even catch the Neil Armstrong photo reference on at least my first few rereads of the book. In fact, it might not have fallen into place until I started getting the (sadly never completed) comic book adaptation back in the day.

The New Sun books are chocked-full of Easter Eggs and layers of meaning. However, I always thought they read just fine as an adventure series, albeit in the baroque vein. These books will stand the test of time. For those who want more background, I recommend THE CASTLE OF THE OTTER. I might have to sit down and reread these for the fifth time.

I love Wolfe’s books and yes they are full of many references and layers of meanings. The polar opposite of today’s stuff where the Orks are Orks, Elves are Elves and the purpose is to try to get money, nothing beyond that.

His New Sun series, I think everyone who’s read it has a favorite or something that sticks in the mind.

My fav is a bunch of “Miners” who are simply digging up remnants of some now long forgotten civilization – including corpse raiding. The people were buried with stuff on them and their bodies transmuted into some kind of plastic. So they strip the bodies, more to re-sell the clothes at market and there are some fancy electronic devices but treated like costume jewelry. And so there’s a pile of naked corpses looking like people resting after the greatest Orgy ever. If I remember right Severian had lunch on top of the pile.

Interesting enough, decades later a guy actually found out how to turn people into plastic and used it for artistic exhibitions of the dead…

I love the latter comments mention of “castle of the Otter” That’s a really brilliant work and good for any fan to read. The “Forgotten English” chapter alone is worth buying it – etext from Google play if you can’t find the book.

One neat thing to note about Gene Wolfe is that in his “New Sun” he doesn’t really make up any “New” words. Scifi is full of Bololgnium, Unobtainium – Fantasy if full of “Lord Wolthor of Trolllg” and Chontran Magick…etc. that the author made up on the fly. Nothing wrong with that, that’s the norm. Wolfe is the exception…

All his words, even the names, aren’t made up. They are “Forgotten English” even if they describe something high tech in a far future. The horses are called “Destriders” and they resemble modern horses but have fanged teeth and leapord like paws instead of hooves. But the “Destrider” is something anyone a century or earlier would easily know was a term for “War-Horse”. So Castle of the Otter goes through the use of language in the books – this was published well before any easy internet access and the new popularity of “Forgotten English”.

Working on my own “Castle of the Otter” type book. Won’t go over details now, save they’ll be for fans and about the creaton process and references used in my own works later.

Darrell Schweitzer had a great interview with Wolfe in one of the Terminus digest issues of Weird Tales. I’d already read New Sun at least a couple of times by the time I got the interview, but it was fascinating to hear what he had to say about, yes, how he came up with a lot of the more obscure terms, and how in a lot of ways he was using Byzantium as a historical model.

Also recommended: Michael Andre-Driussi’s Lexicon Urthus, which provides etymology & definition for most, if not all, of the weird words.

This is one of those series I always figured I’d get around to reading. As with Gormenghast, eventually I’ll have to make it its own occasion. I remember seeing them on bookstore and library shelves through my teens, but sympathizing with a torturer was not really something I was up for at the time. Though the books’ fans have convinced me the story’s virtues balance out the torture, I’m not sure I’ll be up for it now.

But then, I enjoyed so many things about Gormenghast, and I’m still enjoying thinking about even the parts that didn’t work for me. Tell me there’s a touch of Peake in Wolfe, and you’ve got my attention.

[…] is enriched by Wolfe’s detailed prose and atmospheric world-building, which reflects the decaying world of […]