Seleno, the Electric Dog

The 20th century is one long run of wonder elements. Radium dominated the early years, when the magic of X-rays – seeing through solid objects! – created a worldwide sensation. Uranium and atomic power followed after World War II and then it was silicon’s time as driver of the computer age.

Forgotten today is that selenium once stood as high as these three, especially in the years around World War I. Headlines called it the “Mystery Metal” and the “Magic Eye,” that it would “Revolutionize Aerial Warfare” and “Make Blind See” and maybe even be a “Cancer Cure.” Selenium had the property of transforming electromagnetic radiation – visible light, in this case – into electricity, almost as much a miracle as penetrating hands to see the bones underneath.

“Selenium is also used in the observation of the transit of Venus and eclipses of the sun, to light and extinguish buoys automatically, to guide, and explode torpedoes, for measuring X-rays, and in the glass industry,” explained a 1913 Harper’s Weekly article that was widely reprinted in newspapers.

Just as young inventors jumped all over silicon for computer experiments, young inventors of the day played with selenium to harness its powers in way that older researchers, preoccupied with weighty matters like war and health, would never think of.

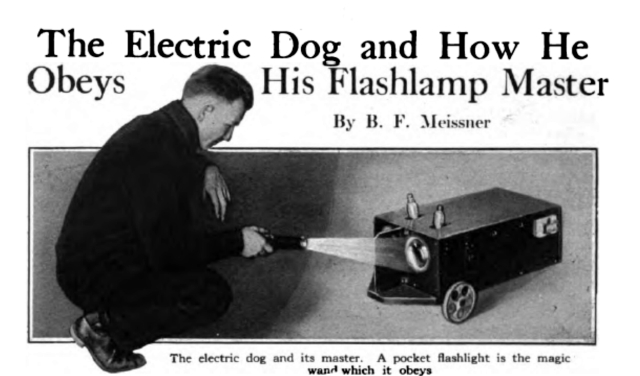

Introducing John Hays Hammond, Jr. [at top] and Benjamin Franklin Miessner [below], whose ages combined in 1912 totaled only 46. [Yes, his name is spelled Meissner in the Popular Science article the image comes from. The “Mie” spelling is correct but magazines and newspapers seemingly alternated between the two by the flip of a coin. Researchers should be prepared to check for both spellings.]

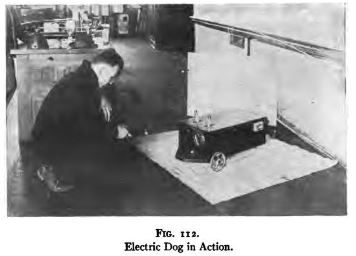

Miessner built a mobile mechanism that would used selenium to respond to light signals, called an “electric dog” probably because the device obeyed its owner’s commands faithfully. He wrote about it in a 1916 book titled Radiodynamics.

The orientation mechanism possesses two selenium cells, corresponding to the two light sensitive organs of the moth, which, influenced by the light effect the control of sensitive relays… [They] in turn control electromagnetic switches which effect the following operations; when one cell or both are illuminated the current is switched onto the driving motor; when one cell alone is illuminated, an electromagnet is energized and effects the turning of the rear steering wheel. The resultant turning of the machine will be such as to bring the shaded cell into the light. As soon and as long as both cells are equally illuminated in sufficient intensity, the machine moves in a straight line toward the light source.

|

|

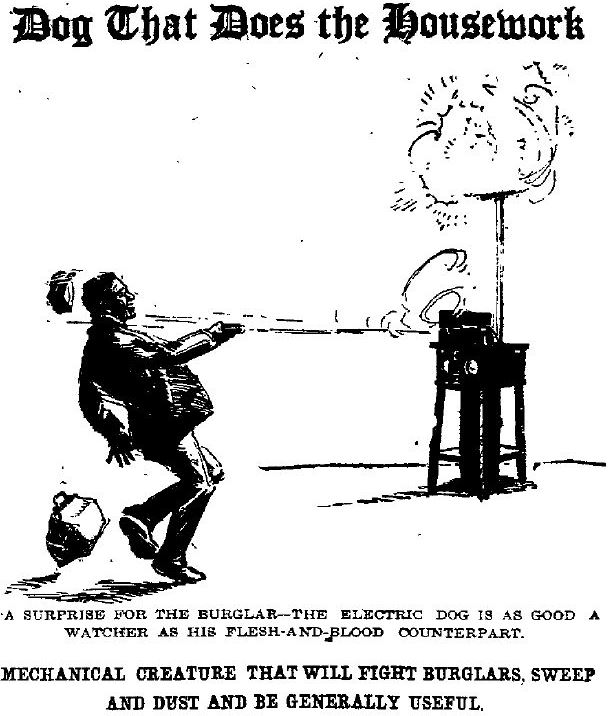

OK, that’s fairly yawn inducing. Real world engineering usually is. But let a seasoned journalist get his hands on the material and its amazing the delicious spin that can be put upon it, as in this excerpt from Technical World magazine, with the illustration coming from its reprinting in the Washington Post.

He is a queer-looking dog. He has only three legs. He doesn’t bark, bite, nor chase the neighbors’ chickens. He is even at peace with the family cat, which purrs contentedly as it watches with speculative mien the peculiar antics of this unknown thing which seems to be at the beck and call of his master. Of course her feline majesty doesn’t know he isn’t a real dog. She judges so only from hearsay — that is, she heard some one say, “Oh, isn’t he a wonderful dog!” – So she trusts her ears and doubts her eyes. This dog possesses none of the malicious characteristics of “Snarleyow, the Dog Fiend.” [An 1833 book.] Rather, he could be likened to faithful “Old Dog Tray.” His cost—that bugbear word in these days of high prices and low wages — is merely nominal. As to food, that is nil. Regarding repose, like the famous detective, he never sleeps. In fact, his every action is guided by the rays that penetrate his material being.

The eyes of this melancholy-looking creature are of bulging glass, each one as large as a saucer. His body is an oblong mahogany box, which contains an electric motor, a storage battery, two selenium cells, two relays, and two solenoid magnets. He has no tail to speak of, but in its place is an electric switch. He is controlled by three brass wheels, two in front and one in the rear.

When the motor inside the dog is started he will do some extraordinary things. If you walk before him carrying a lighted lantern, he will follow you, turning to the right or left as you turn, although you neither touch nor control him in any way that is visible to the spectator. He steers himself briskly after his leader in a way that is positively uncanny. …

He could be used for a burglar alarm, in connection with an electric battery and relay. This may be wired to the alarm bell proper, connected with dry batteries, wherever it may be deemed advisable place the alarm bell — if in the home, in the bedroom of the head of the house; if in the office, the wire may lead to the nearest police station. When the gentlemanly burglar enters the room and flashes his electric pocket light, its rays will strike the selenium cell and the gong will ring. But this is not all that may be accomplished. If a little mechanical ingenuity is brought into play. A revolver and a camera might be added to the equipment to complete the discomfiture of the burglar. The revolver, aimed in his direction, would either cripple him or give him a good fright, while at the same time a flashlight would enable the camera to take a photograph of him.

The reporter also suggests that the electric dog could serve as what we now call a Roomba, but who would remember that? An electric gadget shooting a burglar is what adds wow to the story. I’m not quite sure what happens when somebody in the house turns on a light but no doubt the reporter didn’t spend a moment worrying about it.

An article in the June 1915 Electrical Experimenter revealed that Miessner called his pet “Seleno.” The lead story in the same issue was “Talking Motion Pictures and Selenium,” which presciently stated that synchonization of sound and picture would never occur unless the sound was recorded right on the film itself, and light shining on the recording was sent to a selenium cell for pickup. Electrical Experimenter of course was one of Hugo Gernsback’s magazines, the one in which he printed his series of Baron Munchhausen’s New Scientific Adventures. The cover of that issue illustrated the story with an image of an artificial moon that is the high point of all proto-science fictional pulp covers.

Both Hammond and Miessner went on to solid careers, Miessner filing more than 150 patents and Hammond becoming known as “The Father of Radio Control.” The title concisely explains why large-form selenium-controlled devices never got beyond the headlines. They couldn’t be operated from more than fifty feet away and required line of sight to the originating light source. Radio control, already a thriving industry, surpassed selenium at an early date and swamped it entirely by 1920. Seleno became an interesting curiosity that never led anywhere, but remains a landmark in early robot design.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was A Robot Has No Soul.