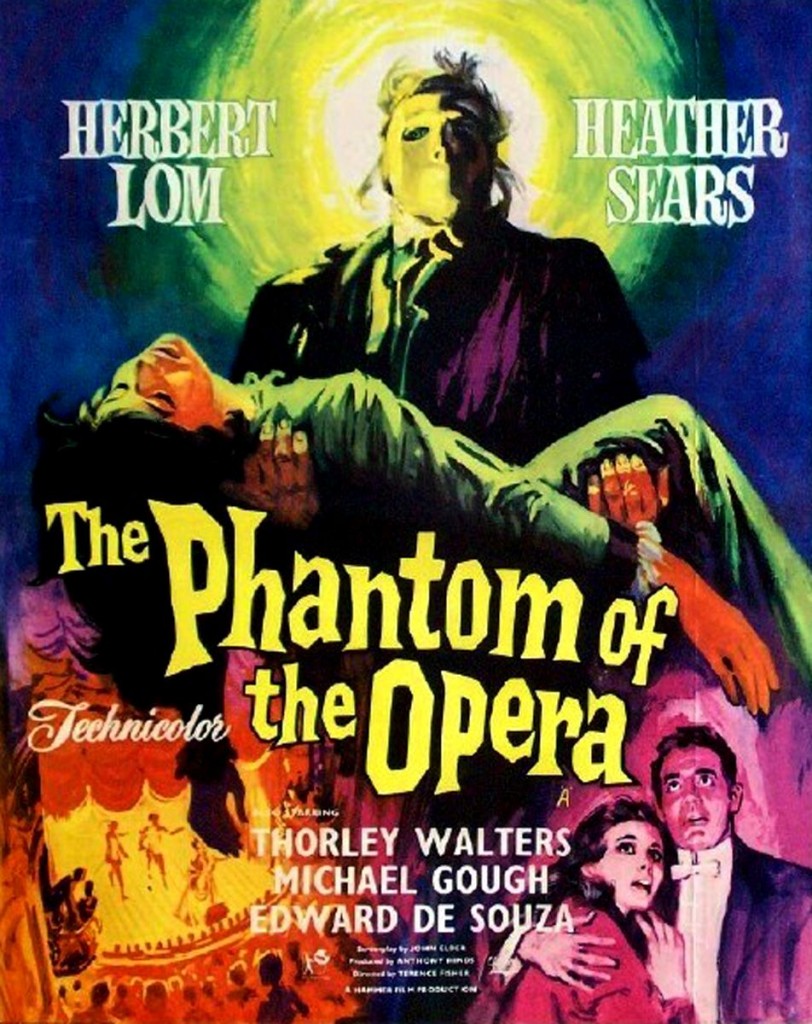

October Is Hammer Country: The Phantom of the Opera (1962)

Ah, October. That means nothing but Hammer Films. All Hammer Horror, All the Time! So let’s start off with one that’s … not so great. (Gotta build up the suspense.)

Ah, October. That means nothing but Hammer Films. All Hammer Horror, All the Time! So let’s start off with one that’s … not so great. (Gotta build up the suspense.)

Once Britain’s Hammer Film Productions received full permission from Universal Pictures to raid their box of monster goodies, a Phantom of the Opera movie was a certainty. Universal had twice adapted the 1910 Gaston Leroux novel. The first is the most famous version, the 1925 silent classic starring Lon Chaney Sr. in his signature role. Its unmasking scene is one of the first iconic horror movie images. Universal mounted a lavish color remake in 1943 with Claude Rains as the phantom, but the musical production numbers were pushed to the front, making for incredibly anemic horror.

Almost twenty years later, the time was right for a new version, and Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera was perfect material for Hammer’s luxurious Gothic style, its seasoned horror director Terence Fisher, and an ideally cast Herbert Lom as the Phantom. But even with this talent involved, The Phantom of the Opera was poorly received in 1962 when it was released on a double bill with Captain Clegg, a period adventure picture about smugglers. The film still maintains a lower profile than other cinematic Phantom adaptations, both literal and loose, of the story of a tortured and murderous composer beneath the Paris opera house. Or, in this case, a London opera house.

The Hammer Phantom is not an undiscovered gem or misunderstood film. It’s a disappointment for Fisher and the studio, an oddly undramatic and slow movie for such a richly overripe concept. Fisher was unhappy with the film, believing the Phantom never had sufficient motives to make him anything but vague to the audience. “What he loves is her voice. He respects her for her voice and she understands that, but that’s hardly true love, is it?” Fisher also disliked the ending, and felt the film “lacked a certain punch. And for that, we’re all responsible.”

Yes, punch is the right word. Phantom ‘62 doesn’t punch hard. Or throw many punches at all, and the ending hardly seems like a climax — it’s merely the last scene before the credits. It isn’t bogged down with extraneous nonsense like the musical drudge of the 1943 version, but it doesn’t have much horror. Herbert Lom’s title character unleashes very little terror on the theater (he only kills one person off screen), and the opera house seems quite capable of crashing and burning on its own because of poor management, no need for a scarred lunatic in a mask do anything extra. It takes fifty minutes to get to a major scene between Christine and the Phantom down in the grottoes. I enjoy what Herbert Lom does as the Phantom — he possesses one of those voices — but Fisher is correct about how the story keeps him too vague for viewers to latch onto, and he doesn’t commit enough atrocities to make him frightening.

The screenplay adapts the novel loosely, but follows the familiar contours of most “Phantom” versions. Struggling musician Professor Petrie (Lom) sells his music, including a complete Joan of Arc opera, to the untrustworthy Lord Ambrose D’Arcy (Michael Gough, Alfred from the Tim Burton Batman), hoping he’ll publish them. D’Arcy does publish them, but with his name on the front. Enraged at this outright theft, Petrie breaks into the print shop to destroy the music, starts a fire, and accidentally scars himself horribly with acid before falling into the river … to become the masked phantom who will torment the London theater where D’Arcy plans to mount “his” opera.

This is all backdrop uncovered in pieces by the film’s effective hero, theatrical producer Harry Hunter (Edward de Souza). Hunter becomes the love interest for Christine (Heather Sears), whom D’Arcy selects as the new lead for the opera after the Phantom scares off their first leading lady. But D’Arcy is a casting-couch sleaze looking to bed Christine, and when Hunter intervenes to stop D’Arcy’s predatory behavior, D’Arcy cuts Christine entirely from the opera. While consoling Christine, Hunter becomes aware of the trail leading to the identity of the Phantom, who has taken an interest in molding Christine’s voice for his opera.

De Souza is striking in the hero part. He’s much better than the usual dishrags who play Christine’s principal love interest, and he has affectionate chemistry with Heather Sears. Viewers actually want to see the two characters end up together. But I don’t want this character to take up so much time. The focus is in the wrong place, and the Phantom is essentially only involved to the extent he wants Christine to sing the opera for him — which Hunter and D’Arcy also want, although D’Arcy has a nasty price for it.

Ambrose D’Arcy is the true villain of the tale. Of all the versions of the story that I’ve seen, no actor has outdone Michael Gough as the target of the Phantom’s wrath. D’Arcy is a skin-crawling, vicious tyrant. Gough appeared in other Hammer films (most prominently as Arthur Holmwood in Dracula), but I’ve never seen him give a better performance for the studio than what he delivers here. Watching him develop a Saturnine smile as he watches another young woman perform is more shivery than the outright horror moments. But Gough’s excellence in the part makes it more unfortunate that the movie seems to have no clue what to do with D’Arcy in the finale. He has a single brief run-in with the Phantom, but it’s not the climax, and the film seems to forget he’s around after that. No comeuppance, no anything. If any character deserves to have a chandelier dropped on their head, it’s D’Arcy.

Terence Fisher had a talent for directing the working-class Londoner characters who wander through the story, like the rat-catcher (played by future Doctor Who Patrick Troughton, also memorable as the doomed priest in The Omen), the scullery women, and the hansom cab driver (Hammer regular Miles Malleson) who worries about getting home in time for the “missus.” On the opposite side of Victorian society, Fisher put real enthusiasm into the presentation of the Joan of Arc opera (original music by Edwin Astley) that concludes the film. It’s not a good finale for a horror movie, but the opera presentation is passionate and colorful, and Heather Sears looks radiant in the lead. As an imitation of grand opera, it’s excellent. It’s just not what I want from the conclusion to a Hammer Gothic.

The Phantom’s mask is key to creating a memorable version of the story, and Roy Ashton’s design is unique: a gray, almost featureless full covering allowing only one eye to peer through. It almost looks like an extension of the Phantom’s gray, rotting skin. Ashton improvised the mask on set after the producer rejected numerous Kabuki-style ideas. “I got an old piece of rag, tied it around [Herbert Lom’s] face, cut a hole in it, stuck a bit of mesh over one of the eyes, two bits of string around it, and tied it. ‘Great!’ they cried out. ‘That is just what we want!’” The scarring underneath the mask isn’t revealed until the finale. The makeup is unusual, but the revelation doesn’t deliver much shock. Nothing can live up to the Lon Chaney Sr. unmasking.

The rest of the production values are top-notch, with the regular Hammer art and costume team doing colorful work and making good use of recycled props. (The ubiquitous triangular candelabra shows up in the Phantom’s lair. Only Michael Ripper appeared in more Hammer movies than this candelabra, and yes he’s here as well.) The budget did present limitations, because the story calls for a grand opera house. The production team had access to a real theater, the Wimbledon Theater — but of course they couldn’t inflict massive damage to it the way Universal could with their opera house, which was a fully constructed set on a soundstage. This put a big limit on the mayhem.

I’m thankful the Hammer Phantom stays away from romanticizing its monster in the way that’s become standard Phantom-fare today. But it never delivers on the horror either. The only shock is a gruesome moment when the Phantom’s mute servant (Ian Wilson) stabs the opera rat-catcher in the eye, which doesn’t affect anything else in the movie. The movie hovers between a shock show and romantic fable, and never finds its tone. It’s still worthwhile to Hammer fans for the production values, as well as Lom and Gough’s performances.

The Phantom of the Opera is currently available in North America on Blu-ray as part of Universal’s Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection, which also includes two better Hammer Gothics I looked at last year, Kiss of the Vampire and The Curse of the Werewolf. The print quality is one of the best on the set.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

I think I’ve seen this once…? The only Phantom movie that’s ever left an impression on me is the Chaney one. I know people today who are completely unaware of the story as anything but an Andrew Lloyd Webber production.

I watched this one relatively recently (as part of the 8-film collection and it was … OK.

I also find it impossible in this day & age to look at the Phantom’s mask and not immediately flash on Michael Myers.

I think the phantom of the opera 1962 is the best film.the phantom was the real hero. It was the dwarf who did the killings not the once handsome phantom.the music is beautiful! I heard the new Wimbledon theatre really has ghosts and would like to.know whether the cast and crew encountered any during the making of this epic masterpiece.