Fantasia 2018: Reflections After the Fact

I saw 60 feature films or showcases of short films this year at the Fantasia International Film Festival. As is the case every year, seeing so many wild visions so close together was a powerful experience. If one film didn’t work, there’d be another one coming right after that’d be completely different. Having been slowed down by a bad cold the last few weeks, I’ve had time to think about what I took away from the Fantasia adventure this year in particular, and I keep coming back to things that struck me during the festival itself: the ability of the programmers to select films; the power of seeing the films as part of an audience and indeed part of a community; and the way those things interact.

I saw 60 feature films or showcases of short films this year at the Fantasia International Film Festival. As is the case every year, seeing so many wild visions so close together was a powerful experience. If one film didn’t work, there’d be another one coming right after that’d be completely different. Having been slowed down by a bad cold the last few weeks, I’ve had time to think about what I took away from the Fantasia adventure this year in particular, and I keep coming back to things that struck me during the festival itself: the ability of the programmers to select films; the power of seeing the films as part of an audience and indeed part of a community; and the way those things interact.

Let me begin explaining that by thanking the Fantasia team for another excellent festival. I particularly want to thank the people who I spoke with and helped me in my coverage, including Rupert Bottenberg, Mitch Davis, Ted Geoghegan, Kaila Hier, and Steven Lee. I also want to thank a number of fellow writers who helped make the festival even more enjoyable. I’ll specifically note here Giles Edwards, Yves Gendron, Dave Harris, Agustín Leon, and Thomas O’Connor.

I mention all these people because I’ve been thinking about what makes the experience of Fantasia different from watching an equivalent number of movies in an equivalent amount of time on Netflix or blu-ray in the comfort of my own home. Some of it’s getting to see the films on a big screen, of course. But much of it also has to do with the experience of having an audience around you, and so of being able to talk about the films afterward. And, especially, it has to do with the quality of the films and their overall character — the identity of the festival, the overall feel of it that shapes the event.

Spending time at Fantasia is a very specific experience and in writing these posts I try to catch moments outside the movies themselves that strike me as characteristic of that Fantasia feel — the way a theatre may be set up for a special screening, or the way an audience reacts to key moments. Several times over the past few years I’ve mentioned that Fantasia audiences can help elevate the experience of watching a film. Enthusiastic, responsive, but not usually obtrusive, they give another dimension of life to a film. You’re watching a story as part of a crowd, part of a collective whose reaction helps shape the pacing and perception of the tale. Films being films, the director has to try to plan ahead for a crowd reaction, and I think Fantasia audiences on the whole rise to a director’s hopes. That means there’s a special value to being able to see a film alongside an audience, different from watching the same film in solitude or even (usually) at a media screening to an audience of critics. So start with that.

Add to it the experience of seeing the film with other writers, people you get to know at the festival, critics whose knowledge of film is extensive and whose perceptions can help you process what you see. People with whom you can discuss the experience of a film. Sometimes, as most spectacularly this year with A Rough Draft, you almost need that shared experience so you can work out what you saw and try to process a particularly bizarre and baffling story. On the other hand, an elliptical or especially allusive film (something like this year’s Under the Silver Lake, say) can grow as you talk about it, as different people suggest new angles or new connections.

Add to it the experience of seeing the film with other writers, people you get to know at the festival, critics whose knowledge of film is extensive and whose perceptions can help you process what you see. People with whom you can discuss the experience of a film. Sometimes, as most spectacularly this year with A Rough Draft, you almost need that shared experience so you can work out what you saw and try to process a particularly bizarre and baffling story. On the other hand, an elliptical or especially allusive film (something like this year’s Under the Silver Lake, say) can grow as you talk about it, as different people suggest new angles or new connections.

That’s a large part of the feeling of spending time at the Fantasia festival, then: the experience of being part of a small community. I used the word ‘adventure’ up above, and there’s something like that at work. You go into a dark space, and see magic before your eyes. And if you go in as a group, your party can come out of it with a shared experience. If that’s something like an adventure story, it’s also something like the initiation ceremonies of a mystery religion; so it is an experience that can be frivolous or can be profound or can be both. The experience of cinema, even in a theatre, doesn’t usually work on me in that way, but the experience of seeing film after film after film has some kind of cumulative meaning that’s difficult to describe.

Some of that meaning, of course, derives from the selection of films. The word “curation” is going through a vogue right now, but there’s a sense in which that’s what the Fantasia programmers do. They pursue films they want to show, and select others from the submissions they receive; perhaps a little like editors putting together an anthology. Different in many ways. They know nobody will be seeing every film in the festival, and maybe there won’t even be anybody who’ll see every film selected by a given programmer. But collectively the programmers create the festival out of the movies that have been made, choosing movies that they think are good and that they know will resonate with a Fantasia audience. The crowd begins to shape its own experience. Some movies are scheduled because they’ll work in this context. Late-night screenings of Uganda’s first action film or a stitched-together webserial are chosen as things that will play well to the kinds of fans the festival draws, the people looking for a certain kind of cinematic event, one in which Fantasia specialises. A certain kind of party; a celebration of cinema and the visions of the impossible.

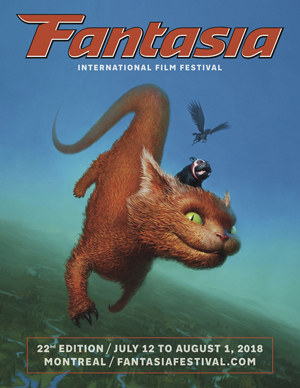

Adventure; party; ceremony; the festival’s something like all of those things and also something else entirely. It’s a distinctive event. Even before covering Fantasia for Black Gate, even when I’d go to just a few movies a year, I could feel that. There’s a sensibility that animates the festival, and it’s visible in the program book and the poster and the spaces the Festival takes up around the Concordia campus. There’s something special in the event, in the time it takes place, with a fixed beginning and fixed ending. It’s something that’s different from the experience of watching films in one’s home. It’s no secret that streaming’s cutting into theatrical revenues, and it’s not hard to see why. But Fantasia’s a strong argument that there’s something special about going out to a specific place to watch, as part of an audience of strangers and friends, a movie projected at much-more-than-life-size play out on a screen. Even to see only one film, I think, is to feel a sense of the occasion.

Adventure; party; ceremony; the festival’s something like all of those things and also something else entirely. It’s a distinctive event. Even before covering Fantasia for Black Gate, even when I’d go to just a few movies a year, I could feel that. There’s a sensibility that animates the festival, and it’s visible in the program book and the poster and the spaces the Festival takes up around the Concordia campus. There’s something special in the event, in the time it takes place, with a fixed beginning and fixed ending. It’s something that’s different from the experience of watching films in one’s home. It’s no secret that streaming’s cutting into theatrical revenues, and it’s not hard to see why. But Fantasia’s a strong argument that there’s something special about going out to a specific place to watch, as part of an audience of strangers and friends, a movie projected at much-more-than-life-size play out on a screen. Even to see only one film, I think, is to feel a sense of the occasion.

So many films these days have their success almost predetermined: play a while in theatres, move to streaming, use an advertising budget to draw attention. That’s not the case at a festival, where films may be playing to an audience for the first time in the world, and may have their fates decided by the way the audiences react. You don’t know what you’re going to see. You don’t know, necessarily, if you will like it. But it is an adventure to find out, as every story is an adventure that plays out in our own minds as we watch or read or listen. As with any adventure worth the name, you don’t know how any movie will end up, not exactly, or whether it will succeed for you or fail. But what I have found is simply that in the long run, Fantasia rewards the adventurous.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.