Fantasia 2018, Day 21, Part 1: Tigers Are Not Afraid

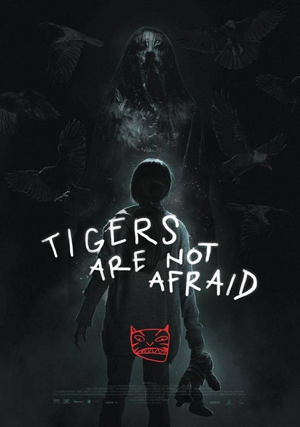

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

The first thing to know about this film is that it’s a powerful story. It’s structured well, paced well, and is tremendously inventive. The characters are alive and well-rounded; the actors are excellent, both Lara and López crafting disturbingly real people. It’s a powerful story, too, dealing with primal emotions about love and abandonment and fear and wonder. Visually, it’s precise, opening up at odd moments in odd places, so that the boys’ rooftop camp feels like a sanctuary, or an old house can feel like an elven palace. Special effects are integrated well and push the reality of the film in exactly the right directions. This is an excellent movie. And it is a profound movie, with a lot to say about storytelling and magic and myth.

The film begins with Estrella in class, taking part in a discussion about fairy tales. From the start, then, the movie does not hide its influences; this is a fairy tale of the modern world. My fellow-critic Giles Edwards observed that there’s a Peter Pan–like sense to the film, with Estrella as Wendy; I note that Lord of the Rings is mentioned explicitly a couple of times in the film, and in fact the agents of evil here chase small people who have an item of potential power that can destroy a kind of dark lord — but which they themselves cannot use. At any rate, beyond any one story there’s a kind of syncretic aspect, pulling together all kinds of childhood fables into the story of these very desperate children; a meta–fairy tale, if you like, a story that uses fairy tale elements deliberately, and as part of its affect establishes up front that this is what it’s doing.

That perhaps sounds over-clever, but although this is a very clever movie it’s never too clever, never too cute. One way or another, there is an elegant interweaving of the fantastic and the grimly real. Much of the film seems to be aiming at an effect of the uncanny, where it’s possible to view the magical as merely the improbably coincidental, but I would argue certain shots in the film that are not from Estrella’s point of view preclude that possibility, and in any event I can’t see how to read the conclusion without accepting the magical as literally true. Does that make the movie fantasy or myth or magical realism? I’m not at all sure it matters. What does matter is the skill with which the story’s unfolded. The fantastic’s used with an understanding of its power. It’s something that transfigures the world — which I think is in part the point of the film.

On Tuesday, July 31, the first movie I planned to see alongside a general audience was a Hong Kong action movie called The Brink. After that, I’d pass by the screening room before heading home. There’d be only two more days of Fantasia after this one, and I wanted to catch up on things I’d missed in theatres. I was specifically curious about a Korean movie called The Outlaws, about a cop who’s working against the clock to catch a Chinese gang who’re trying to take over territory in a district of Seoul. Two promising action movies; I had reasonable hopes for the afternoon.

On Tuesday, July 31, the first movie I planned to see alongside a general audience was a Hong Kong action movie called The Brink. After that, I’d pass by the screening room before heading home. There’d be only two more days of Fantasia after this one, and I wanted to catch up on things I’d missed in theatres. I was specifically curious about a Korean movie called The Outlaws, about a cop who’s working against the clock to catch a Chinese gang who’re trying to take over territory in a district of Seoul. Two promising action movies; I had reasonable hopes for the afternoon.

I was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 31, for a press screening of Mandy. It’s the second film by Panos Cosmatos (director of Beyond the Black Rainbow), who also wrote the script with Aaron Stewart-Ahn. The movie stars Nicolas Cage as Red Miller, a lumberjack who lives in a cottage in the deep woods of the Shadow Mountains with his wife Mandy (Andrea Riseborough), a metalhead artist, in the long-ago year of 1983. Mandy unwittingly catches the eye of a cult leader (Linus Roache), whose minions, the Children of the New Dawn, abduct her. Bad things happen. Miller is tortured. And, inevitably, he embarks on a quest for bloody revenge.

I was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 31, for a press screening of Mandy. It’s the second film by Panos Cosmatos (director of Beyond the Black Rainbow), who also wrote the script with Aaron Stewart-Ahn. The movie stars Nicolas Cage as Red Miller, a lumberjack who lives in a cottage in the deep woods of the Shadow Mountains with his wife Mandy (Andrea Riseborough), a metalhead artist, in the long-ago year of 1983. Mandy unwittingly catches the eye of a cult leader (Linus Roache), whose minions, the Children of the New Dawn, abduct her. Bad things happen. Miller is tortured. And, inevitably, he embarks on a quest for bloody revenge.