Magical Tomes and Witch Hunting Manuals at the Ashmolean Museum

Last week I looked at the new exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft. It’s such a compelling collection of folk magic through the ages that I wanted to look a bit more in detail at a few of the magic books that were included in the exhibition, along with some of the art that belief in witchcraft inspired in pre-modern times.

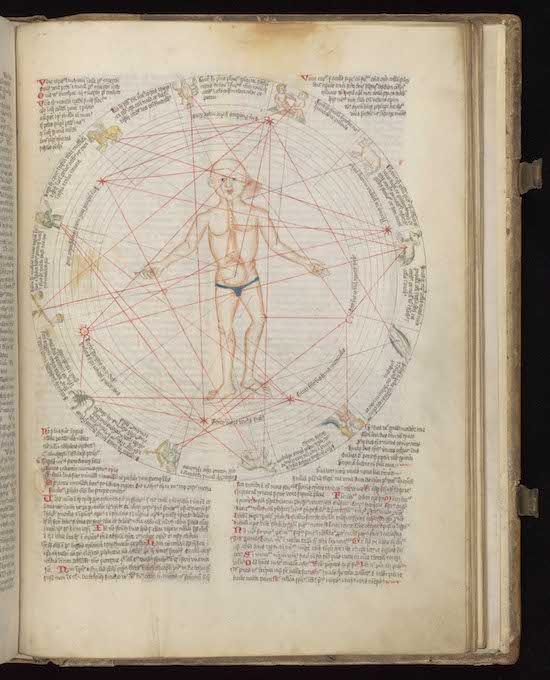

The “microcosmic man” in a German manuscript, c. 1420. © Wellcome Library,

London. The idea that man is a smaller reflection of the greater universe

goes back to Plato and Aristotle, and in the Middle Ages was developed by

astrologers into a system in which certain parts of the body correspond

to signs of the Zodiac. Medical texts used these charts to know whether

or not to bleed a patient. If the moon was in the sign corresponding to

the body part, it was unhealthy to bleed them.

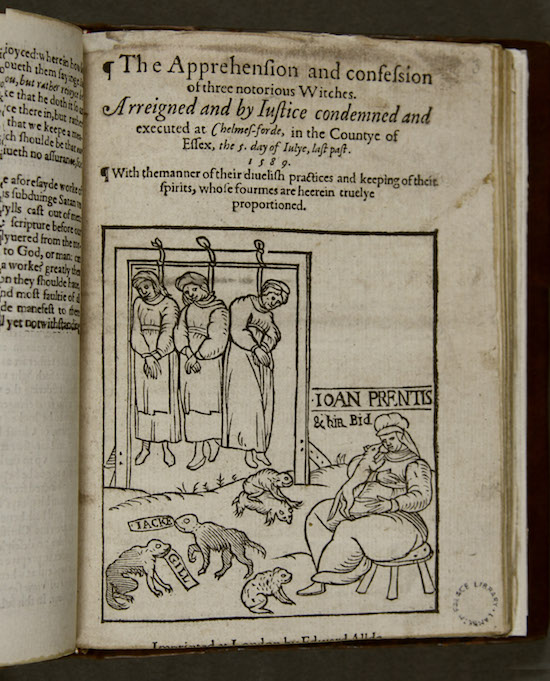

The Apprehension and Confession of three notorious Witches, published in

London, 1589. © Lambeth Palace Library. Accounts of witch trials sold well.

This pamphlet recounts the crimes of three women who were all found guilty

of witchcraft and hanged. Joan Cunny, aged about 80, said that she made a

circle on the ground, knelt within it, and prayed unto Satan. Two sprites

appeared as two black frogs named Jack and Jill and demanded her soul in

exchange for power. Cunny agreed to this. From then on the sprites acted

as her servants, stealing milk from neighbors’ cows, tossing over their

woodpiles, and causing people to get injured. The chief witnesses against

her were her two grandsons, the eldest no more than 12. You can read the

entire text here.

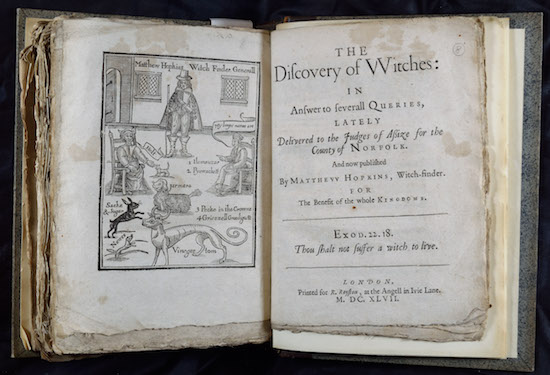

The Discovery of Witches, by Matthew Hopkins, 1647. © The Provost and

Fellows of The Queen’s College, University of Oxford. Hopkins (c.1620-1647)

was a notorious witch finder during the English Civil War, traveling with

safety across a war-ravaged land to root out witches. He charged a fee for

his work and extracted confessions from witches through various methods such

as “swimming”. Since a witch had rejected their own baptism, the water would

reject them and they would float. Another method was “pricking”, using pins

or dull knives to find “witches’ marks”, spots on the body that had no feeling

of pain and did not bleed. Hopkins, of course, was the final judge of what was

or wasn’t a witch mark. He would also use other methods of torture such as

sleep deprivation to gain a confession. He led some 300 people, mostly women,

to the gallows between 1644 and 1646. He charged a hefty fee for his work.

Hopkins’ methods were outlined in this book, which was used as an investigatory

manual in later cases, including the Salem witch trials. You can read the

entire text here.

Just as books about witches were popular, so were paintings. Witches at their

Incantations was painted by Salvator Rosa (1615–73) around the year 1646. Rosa

was a successful Italian painter and considered one of the predecessors to the

Romantic movement. © National Gallery, London.

Interest in witchcraft continued even after people in educated circles no longer

believed in them. Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) drew The Witch and the Mandrake

around the year 1812. The Anglo-Swiss artist was fond of depicting the supernatural,

such as this image of a witch collecting a mandrake root, believed to have magical

properties because it vaguely resembled a person. A mandrake root was said to

scream when pulled out of the ground. © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919.