We Buy Us a Robot

Robot fever first gripped the U.S. in the 1930s. The decade saw a procession of robots across newspaper headlines, with everybody from industrial giant Westinghouse to 13-year-old Bobby Lambert making the news for robots they built. Tens of millions of households owned automobiles, telephones were never far from a hand, families huddled around radios, and electric appliances dotted modern kitchens. The economy might have hit a minor glitch, but despite that – and in many cases because of that, as newspapers strove to carry stories that looked forward to the glistening recovery rather than the gloomy present – robots seemed the obvious choice for the next major technology to invade daily life.

Today’s shrunken Parade magazine can be found mixed with the coupon inserts that fall out of fat Sunday papers. Parade and the few others of its ilk are sad remnants of the glory days of Sunday weeklies, also experiencing a heyday in the 1930s. Scores, maybe hundreds, of papers carried The American Weekly, boasting “Greatest Circulation in the World.” Full of photos and drawings, the American Weekly was part newsreel, part encyclopedia, part lending library, part gossip column, something for everybody. (Trivia note: fantasy giant A. Merritt became the editor in 1937 and brought in Virgil Finlay as artist the next year.) The lead story in the hefty 21″x15″ 24-page issue of March 19, 1933 was “How the Mysterious Mayans Made War.” In between chapters from serialized novels – a western and a romance – lay the unreachable and unaffordable “New Parisian Decolletes,” the pro-eugenics “Why Intelligent Parents Ought to have Intelligent Children,” the man who “Builds a ‘City for His Pigeons,” and “We Buy Us a Robot – and What Happened.”

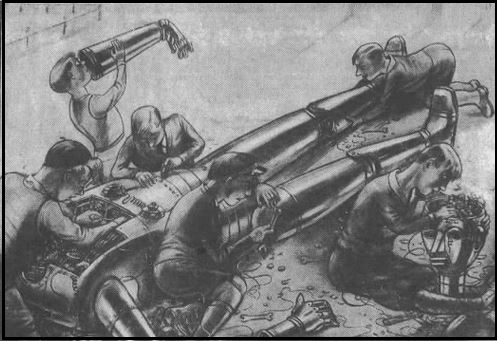

The story, science fiction in all but name, is by the “distinguished German novelist” Frederick Kroner. I can’t find any trace of his existence but the piece is clearly set in Germany and contains illustrations by “Mr. Charles Girod, the well-known Berlin artist.” Germany still considered itself the most technologically advanced country, with dirigibles, rocket cars, and other proto-science fictional concepts filling their daily newspapers. Why not robots next?

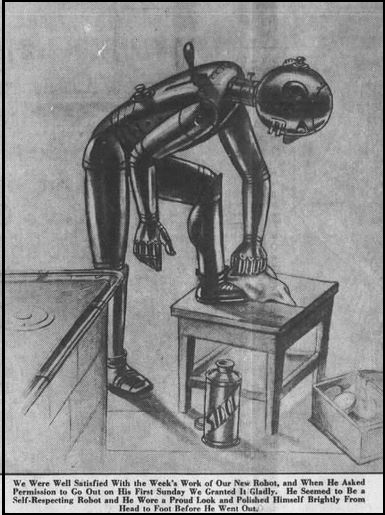

The robot is bought in the far-off technological future of 1950. Just as happens with cars, a couple’s household robot, nicknamed “Willy,” is a “crude, old-fashioned” model a full eight years old, a literal rattletrap who also creaked and broke dishes. Willy didn’t care. He had no emotions. Scolding him meant nothing, discipline was meaningless, strictures no more useful than sending an erratic car to stand in a corner. He obeyed all orders literally unless a part went unlubricated. Servant or no, a robot was simply a machine.

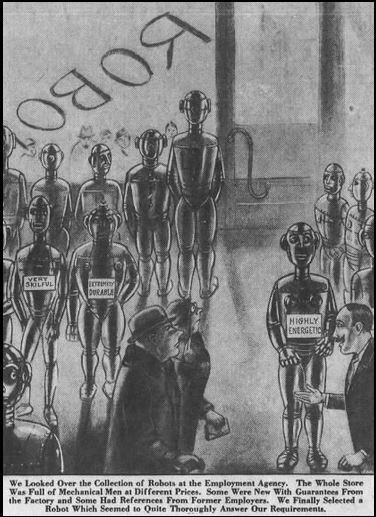

Science to the rescue. If robots need to care about their jobs to get them right, then care they shall. The all-new Superfix robot of 1950 is on the salesfloor. Sold as with cars by touting the latest and greatest gadget, in this case emotions, it costs as much a new car as well, $460, almost exactly the price of the then new and touted 1933 Plymouth 6. The wife (neither half of the couple is ever named) is taken by his looks, a perfect reproduction of her favorite radio moving picture hero, Rudolph Octaviano, and by his adjustability. A little set-screw under his left ear varies “his sensitivity at any desired degree from stony-hearted callousness to one in which he will have hysterics at your slightest frown,” the salesman explains.

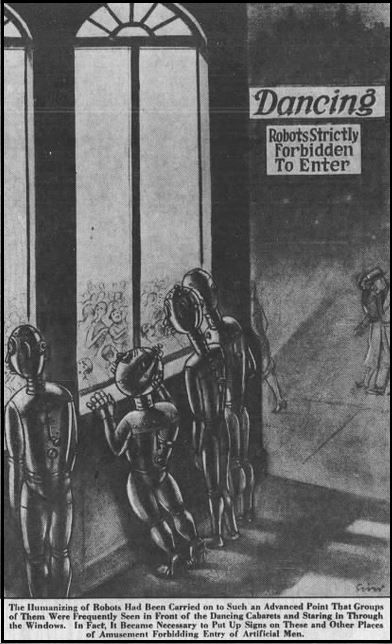

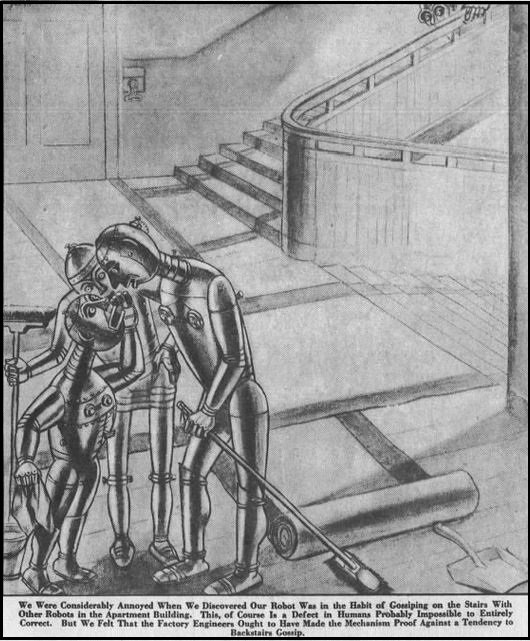

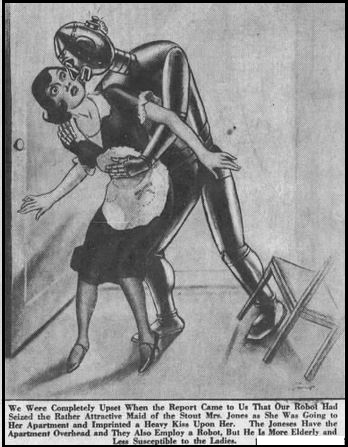

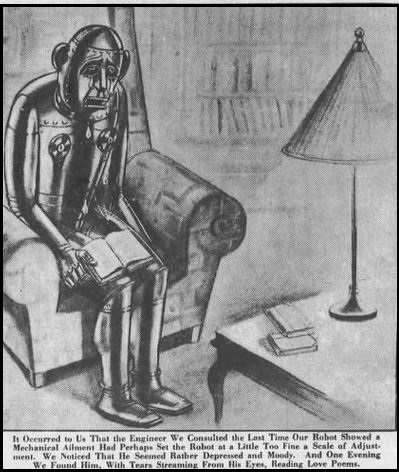

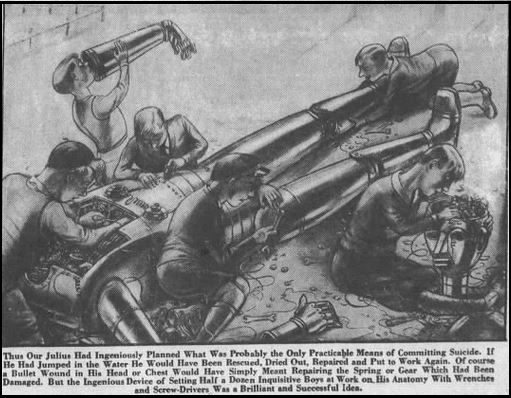

But a robot with emotions is a robot who will act like a human, negating the entire point of having a robot. Such a robot might, gasp, even fall in love. Any radio motion picture viewer of the 1930s knew what happened when man, woman, or robot falls in love. And so when the robot named “Julius” starts to read poetry, the end is nigh.

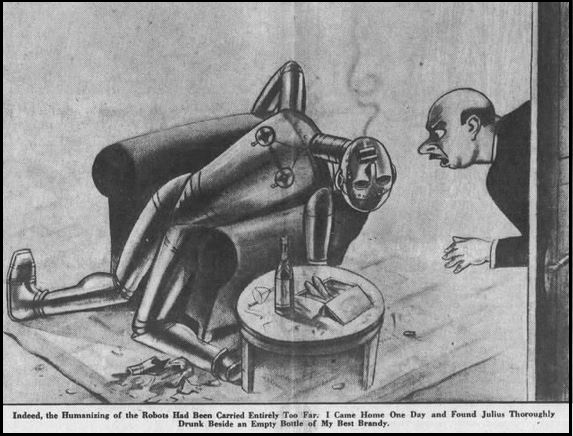

Fortunately, rather than my paraphrasing the rest of the sad tale, the captions to Girod’s illustrations recapitulate the story in much pleasanter fashion.

For the first time in 85 years, “What Happened.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What readers could have made of this weird fable is hard to know. They didn’t really need science fiction to tell them that the future wouldn’t be as bright as the headlines implied. They also had a generation of technology to tell them that although machines made lives easier they also broke down in exasperating ways. Kroner’s fable, modern as it must have read in 1933, is merely yet another in the ongoing series, Robots: They’re Just Like Us.

Update: The original article appeared in the November 1932 UHU magazine in Germany, as by Friedrich Kroner. Thanks to the link Jay provided here’s the first page of that article with an extra image that the American article didn’t copy.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was A Robot to Keep the English Language From Dying Out. His book on the history of robots in popular culture is scheduled for a 2019 release.

Friedrich Kroner was the editor of UHU magazine, here’s the original:

https://magazine.illustrierte-presse.de/en/the-magazines/werkansicht/dlf/73649/60/0/

That’s terrific, Jay. Many thanks for finding that. I did come across “Friedrich Kroner” and UHU but I couldn’t assume he was the same person as “Frederick.” And my German is nonexistent.