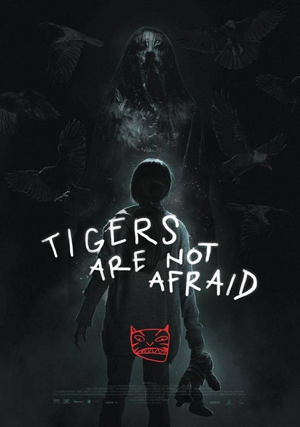

Fantasia 2018, Day 21, Part 1: Tigers Are Not Afraid

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

The first thing to know about this film is that it’s a powerful story. It’s structured well, paced well, and is tremendously inventive. The characters are alive and well-rounded; the actors are excellent, both Lara and López crafting disturbingly real people. It’s a powerful story, too, dealing with primal emotions about love and abandonment and fear and wonder. Visually, it’s precise, opening up at odd moments in odd places, so that the boys’ rooftop camp feels like a sanctuary, or an old house can feel like an elven palace. Special effects are integrated well and push the reality of the film in exactly the right directions. This is an excellent movie. And it is a profound movie, with a lot to say about storytelling and magic and myth.

The film begins with Estrella in class, taking part in a discussion about fairy tales. From the start, then, the movie does not hide its influences; this is a fairy tale of the modern world. My fellow-critic Giles Edwards observed that there’s a Peter Pan–like sense to the film, with Estrella as Wendy; I note that Lord of the Rings is mentioned explicitly a couple of times in the film, and in fact the agents of evil here chase small people who have an item of potential power that can destroy a kind of dark lord — but which they themselves cannot use. At any rate, beyond any one story there’s a kind of syncretic aspect, pulling together all kinds of childhood fables into the story of these very desperate children; a meta–fairy tale, if you like, a story that uses fairy tale elements deliberately, and as part of its affect establishes up front that this is what it’s doing.

That perhaps sounds over-clever, but although this is a very clever movie it’s never too clever, never too cute. One way or another, there is an elegant interweaving of the fantastic and the grimly real. Much of the film seems to be aiming at an effect of the uncanny, where it’s possible to view the magical as merely the improbably coincidental, but I would argue certain shots in the film that are not from Estrella’s point of view preclude that possibility, and in any event I can’t see how to read the conclusion without accepting the magical as literally true. Does that make the movie fantasy or myth or magical realism? I’m not at all sure it matters. What does matter is the skill with which the story’s unfolded. The fantastic’s used with an understanding of its power. It’s something that transfigures the world — which I think is in part the point of the film.

The class discussion of fairy tales is interrupted by gunfire. Estrella’s given three pieces of chalk, which she’s told are magic; they hold wishes in them. As we’ll see, this is true, though the wishes are monkey’s-paw wishes that rebound against the wisher in unwished-for ways. But the point is that there’s something symbolically precise that the items that hold wishes are implements of art, of writing and of drawing. The telling of stories and the making of art is important in this movie; we’ll see the boys painting graffiti on city walls, and see the graffiti come to life. And we’ll hear about the stories the characters tell each other.

The class discussion of fairy tales is interrupted by gunfire. Estrella’s given three pieces of chalk, which she’s told are magic; they hold wishes in them. As we’ll see, this is true, though the wishes are monkey’s-paw wishes that rebound against the wisher in unwished-for ways. But the point is that there’s something symbolically precise that the items that hold wishes are implements of art, of writing and of drawing. The telling of stories and the making of art is important in this movie; we’ll see the boys painting graffiti on city walls, and see the graffiti come to life. And we’ll hear about the stories the characters tell each other.

In these stories, Shine’s lost boys are princes and they are tigers. And both at once: “He’s king of his fucked-up country,” as Shine describes the tiger of his dreams. He’s got a tiger mask he wears, while the youngest boy, Morrito (Nery Arredondo) carries a stuffed tiger. By the end of the film we understand: “They are kings of this kingdom of broken things.” But it takes time and pain to get there: “We forget we are princes, warriors, we forget who we are when things from outside come to get us.” And there are things from outside, for the cartel gangsters are rumoured to be Satanists, and the phone’s unlocked by the code 6-6-6.

Estrella finds a place with the boys, despite some inevitable gender friction. It’s well-observed, but it also helps set up a symbolic theme. When Estrella finds the man responsible for her mother’s disappearance she’s challenged to “turn into a man,” a comment reflected by a phallic gun not long after. At another time Shine commands the gang to run with “Hey Disney princess! Move it!” The fairy-tale image is right, and the movie intrigues with its observation of gender, and symbolic hints at gender instability.

This is a symbolically dense movie, and yet graceful in the rapidity and sureness of the storytelling. Incidents move the story forward and keep broadening the world, as when the boys find sanctuary in an old house, or when the dead speak to Estrella. It’s unpredictable and yet logical. The climax pulls together all the strands of the symbolism and of the narrative with seeming effortlessness. Shine turns against stories, insisting “we’re all there is,” but in a movie like this, where metaphors are literalised, it’s no surprise to find that things don’t end there; that is not the end of the story.

This is a symbolically dense movie, and yet graceful in the rapidity and sureness of the storytelling. Incidents move the story forward and keep broadening the world, as when the boys find sanctuary in an old house, or when the dead speak to Estrella. It’s unpredictable and yet logical. The climax pulls together all the strands of the symbolism and of the narrative with seeming effortlessness. Shine turns against stories, insisting “we’re all there is,” but in a movie like this, where metaphors are literalised, it’s no surprise to find that things don’t end there; that is not the end of the story.

Tigers Are Not Afraid is an excellent film and a great work of the fantastic. There’s childlike wonder confronting the harshest aspects of the adult world. There’s magic and evil. There’s visual poetry and there are fairy tales. It’s a powerful film that succeeds in every aspect I can think of. It’s incidental to say that it’s one of the best fantasy stories I’ve seen in any medium in the past several years.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I loved this film. If I had to make a list of my favorite Fantasia films this year, this would be at the very top.

– Agustin