Fantasia 2018, Day 20, Part 1: Mandy

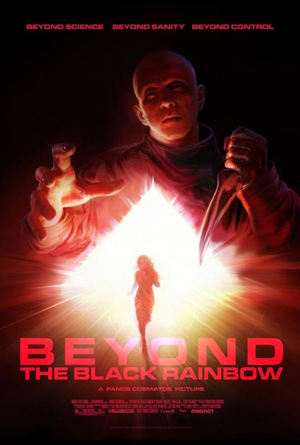

I was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 31, for a press screening of Mandy. It’s the second film by Panos Cosmatos (director of Beyond the Black Rainbow), who also wrote the script with Aaron Stewart-Ahn. The movie stars Nicolas Cage as Red Miller, a lumberjack who lives in a cottage in the deep woods of the Shadow Mountains with his wife Mandy (Andrea Riseborough), a metalhead artist, in the long-ago year of 1983. Mandy unwittingly catches the eye of a cult leader (Linus Roache), whose minions, the Children of the New Dawn, abduct her. Bad things happen. Miller is tortured. And, inevitably, he embarks on a quest for bloody revenge.

I was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre early on Tuesday, July 31, for a press screening of Mandy. It’s the second film by Panos Cosmatos (director of Beyond the Black Rainbow), who also wrote the script with Aaron Stewart-Ahn. The movie stars Nicolas Cage as Red Miller, a lumberjack who lives in a cottage in the deep woods of the Shadow Mountains with his wife Mandy (Andrea Riseborough), a metalhead artist, in the long-ago year of 1983. Mandy unwittingly catches the eye of a cult leader (Linus Roache), whose minions, the Children of the New Dawn, abduct her. Bad things happen. Miller is tortured. And, inevitably, he embarks on a quest for bloody revenge.

There are films that experiment with the artform of cinema, using sound and visuals in unconventional ways to inspire in the audience strange emotions or new states of mind. And there are grindhouse movies that use revenge plots, violence, buckets of fake blood, power fantasies, maybe a bit of sex, and whatever else comes to hand to entertain the hindbrain of the audience. And then there’s this movie, which does both at once. Mandy is both for the arthouse and the grindhouse, and the match is perfectly harmonious.

This might make it sound like a Quentin Tarantino project, and I suppose there are some points of resemblance; like a Tarantino film, it starts with an exploitation-movie plot. But rather than play with structure or dialogue it uses things like weird lighting effects, sound design, and hypnotic pacing to almost slip past the conscious mind of the viewer. It’s surreal in a way Tarantino never approaches. It’s much more Lynchian, in the way it’s not afraid to slow down to a doped-up pace and in the way it pays attention to soundscapes and in the way it’s not afraid to show a character reacting to something in an almost uncomfortably long take. (There’s even a backdrop near the end that seems to have been borrowed from a certain eccentric psychiatrist in the town of Twin Peaks.)

The aesthetic here is utterly bizarre, shaped by early heavy metal and 80s horror and fantasy paperbacks (from which Mandy reads aloud). Lurid light fills the sky, even at night. Long synthesizer notes and slow doom metal fill the soundtrack, a perfect match to the madness onscreen. Nature photography turns the forests and mountains into suburbs of hell. Animated sequences provide further sci-fi visions. The movie’s nominally set in the real world, but doesn’t feel like it. And then there’s Nicolas Cage.

You would think that a psychedelic revenge film would be the perfect vehicle for Cage to push himself to previously unexplored levels of freaking out; and you’d be right. His performance, under other circumstances, would be stunning. Here it simply fits the world of the film. Red Miller’s driven to the edge of sanity, at points a raw bleeding mass of pain and emotion — and yet to me there’s a sense that Cage’s performance is absolutely under control. He’s no more over-the-top than the movie around him. A bad actor could not play this part, and nor could a cartoon. I can’t exactly call what Cage does subtle, but it feels precise; he’s telling Red’s story.

You would think that a psychedelic revenge film would be the perfect vehicle for Cage to push himself to previously unexplored levels of freaking out; and you’d be right. His performance, under other circumstances, would be stunning. Here it simply fits the world of the film. Red Miller’s driven to the edge of sanity, at points a raw bleeding mass of pain and emotion — and yet to me there’s a sense that Cage’s performance is absolutely under control. He’s no more over-the-top than the movie around him. A bad actor could not play this part, and nor could a cartoon. I can’t exactly call what Cage does subtle, but it feels precise; he’s telling Red’s story.

There’s a lack of irony here at the same time as a complete self-consciousness. It’s an effective combination. The story’s simple, a contrivance off of which to hang performances and moments and line deliveries and weird visual and sound effects. It’s almost a ritual, a way to lead the audience somewhere utterly other.

Weird things happen in this movie. The cultists summon forces to kidnap Mandy with a power-object called the Horn of Abraxas. Those forces are the Black Skulls, who ride black motorcycles that are only seen at night and who have the guise of demons. To kill them and the cultists Miller forges his own axe, not a normal shaped axe but something out of a video game or an extraterrestrial’s armoury. Also, there’s a duel with chainsaws. There are gestures toward explanations for some of these things, if not all, but the point is that collectively and along with the rest of the film they create a world and create a way to enter into that world.

Is it worth entering into? If the story’s just about revenge killings, is that enough? In this case, I think so. I think the simplicity of the plot enhances the ritualistic feel of the film. You’re watching characters working their way through stages of a story you already know, but the specifics are unexpected and the way the film looks and feels has a dreadful sense of meaning to it. As in a dream or in certain mental states, there’s a sense of significance that perhaps is its own reward.

Is it worth entering into? If the story’s just about revenge killings, is that enough? In this case, I think so. I think the simplicity of the plot enhances the ritualistic feel of the film. You’re watching characters working their way through stages of a story you already know, but the specifics are unexpected and the way the film looks and feels has a dreadful sense of meaning to it. As in a dream or in certain mental states, there’s a sense of significance that perhaps is its own reward.

It’s partially paradoxical, then, that the first half or so of the movie is more interesting, at least to me. In that part the revenge plot doesn’t feel inevitable. There are more possibilities, and the strange rhythms of the film emphasise that. You don’t quite know what’s going to happen. In the long run it’s clear that scenes between Miller and Mandy in their forest home are setting up his later rage and drive for vengeance. But in the moment there’s a kind of eternal sense, as though their love is in itself important; as though the movie might after all fly off in some other direction.

I came out of the movie dissatisfied. I thought it worked, and did what it wanted to do, but felt it was overall too slow. I thought then that moments where Miller is given exposition to set up the plot feel forced. But now I’m not sure. As I mentioned at the start, I saw the film in the early morning, when I was about as bright and alert as I get. What if I’d seen it at the end of the day? You can’t know, or I can’t; but the sensibility of the movie was clear even in the frame of mind I’d had. Cosmatos swings for the fences in this movie, and in retrospect there are so many different devices and techniques all bent toward one end I wonder what a second viewing would do for me. As I consider the movie I think the end it aims at is not necessarily to do with narrative. There is a solid story here, but it’s a simple one. The trick of it is rather in the telling. This is a film that aims at forging an axe to take to the frozen sea within us, and a strange axe it is indeed. It didn’t quite work for me at the first viewing, but it’d be worth giving it another shot, I think.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

And finishing up my barrage of comments on your reviews, I finally come to this. I’m glad your point of view changed a bit from when we spoke about the film immediately afterwards.

For your pleasure, I have found a couple of oddities on YouTube, one of which adds more substantially to “Mandy”‘s narrative than the film itself does. Look up “Jeremiah Sand – Amulet of the Weeping Maze” and you’ll find two things: the first of which is the full 7-minute(!) version of the God-awful song that plays during the cult-leader’s encounter with Mandy. The second is a seventeen-minute spoken word bit from him, in character, telling the history of how he came to know his greatness and destiny.

And before I duck out, your description of Cage’s performance is perfect: in “Mandy” he has finally found a movie that can keep up with him at his most … energetic.

Yeah, it was one of those movies that gained a lot the more I thought about it and the way certain images tended to gain with time.

Thank you for these links! The second one reeaallly sounds like something out of a Lynch movie.

You’re welcome. They were an odd little find. (And a strange bit of marketing?)

I managed to see “Mandy” again last night — it’s only screening in the Capital District area. I was as pleased to see it the second time as I was the first. (I also got to spread the gospel, hauling my brother-in-law and a buddy of his to check it out.)

I’m not saying I’ve had dreams necessarily like “Mandy”, but the second viewing really emphasized the dream-like nature of the narrative — it’s possibly the closest I’ve seen in film to capture (and maintain) a coherent dream “feel”.