Fantasia 2018, Day 19, Part 2: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? and Tokyo Vampire Hotel

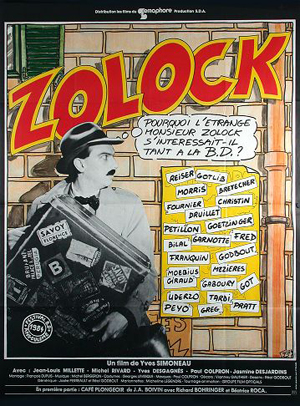

The Centre Cinéma Impérial is one of Montréal’s last surviving movie palaces. Built in 1913 as a vaudeville playhouse, it’s survived most of the past hundred years and change as a cinema. In 1996, the inaugural edition of the Fantasia International Film Festival was held at the Imperial, and Fantasia still returns there for a few screenings every year. It’s a beautiful location in which to view a movie. Currently boasting over 800 seats (including some up in a balcony), it has gilded scrollwork, putti, a proscenium arch around the screen. About twenty minutes’ walk east of the main Fantasia theatres in Concordia University’s downtown campus, it was my destination on the evening of Monday, June 30, for a screening of a 1983 documentary by veteran Québec director Yves Simoneau (perhaps best known to American genre fans for directing four of the first five episodes of the 2009 reboot of V). After that, I’d be hurrying back to the Hall Theatre for a crazed Japanese action-horror dark-comedy thrillride, Tokyo Vampire Hotel. First, though, I’d get to see the recently-restored 35-year-old documentary about European comics, Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée?

The Centre Cinéma Impérial is one of Montréal’s last surviving movie palaces. Built in 1913 as a vaudeville playhouse, it’s survived most of the past hundred years and change as a cinema. In 1996, the inaugural edition of the Fantasia International Film Festival was held at the Imperial, and Fantasia still returns there for a few screenings every year. It’s a beautiful location in which to view a movie. Currently boasting over 800 seats (including some up in a balcony), it has gilded scrollwork, putti, a proscenium arch around the screen. About twenty minutes’ walk east of the main Fantasia theatres in Concordia University’s downtown campus, it was my destination on the evening of Monday, June 30, for a screening of a 1983 documentary by veteran Québec director Yves Simoneau (perhaps best known to American genre fans for directing four of the first five episodes of the 2009 reboot of V). After that, I’d be hurrying back to the Hall Theatre for a crazed Japanese action-horror dark-comedy thrillride, Tokyo Vampire Hotel. First, though, I’d get to see the recently-restored 35-year-old documentary about European comics, Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée?

The screening was preceded by a presentation. Marc Lamothe, one of the Festival’s General Directors, recalled the early years of Fantasia at the Imperial Theatre. Marie-José Raymond spoke about the restoration; she’s one of the co-directors of Éléphant: mémoire de cinéma Québécois, a project dedicated to restoring and digitising Québec feature films. She was followed by businessman Pierre-Karl Péladeau, then by Simoneau and some of the local artists who participated in the film. Simoneau was presented with the Prix Denis-Héroux for his contribution to Québec cinema.

Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? won a Genie award (the Canadian film industry awards from 1980 to 2012, now the Canadian Screen Awards) for Best Feature Length Documentary. Written by Marie-Loup Simon, it follows a private investigator named Dieudonné (Michel Rivard) who’s hired by a mysterious man named Zolock (Jean-Louis Millette) to investigate the appeal of bandes dessinées — French comic books. Dieudonné himself seems to have stepped out of a comic, in his trenchcoat and fedora; Zolock too, a master criminal whose house is dominated by a black room where Zolock first meets Dieudonné, and, at the end, explains his interest in comics. In between, Dieudonné travels about and interviews the leading European and Francophone comics artists of the day.

The result is a murderer’s row of comics talent. Very nearly every major figure in European comics alive and working at the time makes at least a brief appearance here. Interviewees include, in no particular order, Jean Giraud (Mobius), Hugo Pratt, Claire Bretécher, Philippe Druillet, Albert Uderzo, Pierre Culliford (Peyo), Maurice De Bevere (Morris), Franquin, Jacques Tardi, Yves Got, Annie Goetzinger, and Enki Bilal — as well as Québec artists Garnotte, Serge Gaboury, Réal Godbout, and Pierre Fournier. The names alone make this film a major document in comics history.

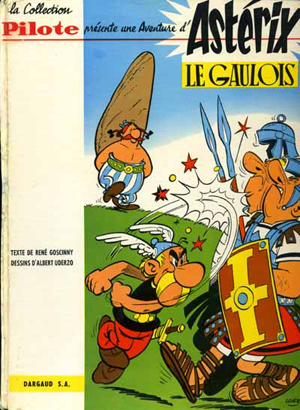

But beyond choosing good subjects, Simoneau selects interesting bits from the interviews he’s conducted, and manages to transition between them fairly smoothly. Again and again a creator will say something intriguing about their process, or about cartooning in general. Got discusses how a character needs a memorable profile to be recognisable. Bilal talks about the importance of colour and how he goes through his pencil drawing quickly so he can create atmosphere with his colour work. Fournier and Godbout discuss collaborating on their character Michel Risque, and observe that it’s a successful collaboration when the reader can’t tell who wrote what in the script. Druillet talks about deciding to do comics through only single-page illustrations and double-page splashes. Peyo’s thoughts on the commercial popularity of the Smurfs, and dealing with Americans who thought they knew better than he how to tell Smurf stories, are set against Uderzo’s declaration that doing commercials with Astérix would weaken the character, and Morris’ reflections on attempts to censor the gunplay and cigarette smoking of his Lucky Luke in adaptations.

But beyond choosing good subjects, Simoneau selects interesting bits from the interviews he’s conducted, and manages to transition between them fairly smoothly. Again and again a creator will say something intriguing about their process, or about cartooning in general. Got discusses how a character needs a memorable profile to be recognisable. Bilal talks about the importance of colour and how he goes through his pencil drawing quickly so he can create atmosphere with his colour work. Fournier and Godbout discuss collaborating on their character Michel Risque, and observe that it’s a successful collaboration when the reader can’t tell who wrote what in the script. Druillet talks about deciding to do comics through only single-page illustrations and double-page splashes. Peyo’s thoughts on the commercial popularity of the Smurfs, and dealing with Americans who thought they knew better than he how to tell Smurf stories, are set against Uderzo’s declaration that doing commercials with Astérix would weaken the character, and Morris’ reflections on attempts to censor the gunplay and cigarette smoking of his Lucky Luke in adaptations.

There’s also a discussion of the history of European comics, beginning in 1911 with strips and books such as Bécassine and Les Pieds Nickelés, continuing in the 20s with Alain Saint-Ogan’s Zig et Puce, created just before Hergé created Tintin. This led to Pilote, the magazine in which Astérix first appeared; Uderzo here spoke about how the character was created to be typically French, in opposition to American heroes and pseudo-Tintins. As of 1983, according to the film, over 100 million Astérix albums had been sold; the internet tells me that by 2013, that figure had risen to 352 million.

What may be most fascinating is how so many of the artists disclaim any desire to transmit ideas as such. Garnotte in particular makes the point that he feels comics aren’t an effective way to get someone to change their minds — but a good way for him to reach out to others who already think as he does, and show them that they’re not alone.

What may be most fascinating is how so many of the artists disclaim any desire to transmit ideas as such. Garnotte in particular makes the point that he feels comics aren’t an effective way to get someone to change their minds — but a good way for him to reach out to others who already think as he does, and show them that they’re not alone.

Visually, the documentary’s basically realistic during the interviews, but tries a few visual conceits during the bookend segments as well as at odd moments during Dieudonné’s quest. Occasionally a character from the comics will pop up for a cameo, wandering through the story as a way of linking segments together. Dieudonné himself helps bind the bookend pieces to the interviews, and emphasises the film’s approach to playing with the real and the unreal. There’s a caricatural aspect to him, not quite a comic come to life but close enough to feel like a part of both worlds.

Simoneau also finds a number of good locations for his interviews. Some are outdoors, in a train cutting or on a river bank. But of course the most intriguing are in the artists’ own studios, where you can see how neat or messy their workspaces are, whether there’s a window giving them natural light, how many reference works they have, and so on. It’s another way to get information across about the artists and their work, a subtle visual comment.

It’s notable how little the film feels distinctively of its specific moment. There’s a kind of timelessness to the artists talking about their work, as though the process of creating comics has an eternal aspect to it. There is a moment in an interview with Peyo when the Belgian comments on issues arising from the fact that Belgium is a country with two languages — “Vous aussi, je crois,” he adds: You too, I believe. In 1980, Québec had held its first referendum on seceding from Canada, and issues of language had been mixed up in the politics swirling around the vote; that’s touched on lightly by Peyo’s comment. But otherwise I didn’t spot very much specific to the early 80s in the interviews that are the meat of the film.

From an Anglophone North American perspective, 1983 was an interesting time. The direct market was growing and giving rise to a movement of independent comics. Cerebus and Elfquest had been around for a few years. The first issue of Love & Rockets had appeared late in 1982. My understanding (coming along as a reader a little later) was that European comics were more accessible to Americans than Japanese manga, if only through translations in Heavy Metal magazine. I’m a little surprised this film didn’t draw more interest, or have more of an effect.

From an Anglophone North American perspective, 1983 was an interesting time. The direct market was growing and giving rise to a movement of independent comics. Cerebus and Elfquest had been around for a few years. The first issue of Love & Rockets had appeared late in 1982. My understanding (coming along as a reader a little later) was that European comics were more accessible to Americans than Japanese manga, if only through translations in Heavy Metal magazine. I’m a little surprised this film didn’t draw more interest, or have more of an effect.

I’d like to think it’ll find some kind of audience now. As far as I can tell it’s now available for streaming in Québec through the Illico service, but should soon appear on iTunes with English subtitles. I’m glad of that; it’s a wonderful piece of comics history. At barely 70 minutes it’s very short, but its selection of interviewees is astonishing, the movement from one interview to another is handled naturally, and the reflections of the creators are fascinating. If you have any interest in the history of comics, this film is essential viewing.

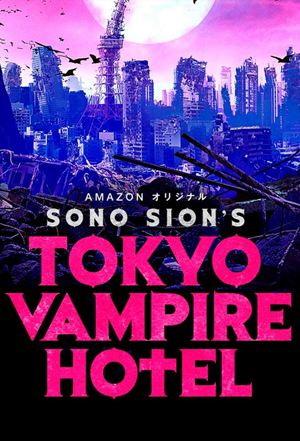

I ducked out of the question-and-answer period that followed Monsieur Zolock for the sake of getting back to the Hall Theatre to watch Tokyo Vampire Hotel (東京ヴァンパイアホテル). The media line wasn’t as long as I’d expected, and luckily some friends of mine were already there, so I got a good seat for one of the more entertainingly bizarre films of the festival.

In 2021 there are two warring vampire clans, the Draculas and the Corvins (the latter named, with uncharacteristic historical accuracy, for the Hungarian king who imprisoned Vlad the Impaler for a dozen years). The Draculas are imprisoned underground, but 22 years before, a child was born who could be the key to their victory. Both sides are therefore after the 22-year-old Manami (Ami Tomite), who is about to come into her full power. The most sympathetic of her hunters, or least unsympathetic, is the Dracula vampiress K (Kaho). But her Corvin enemy Yamada (Shinnosuke Mitsushima, Blade of the Immortal) imprisons Manami at the Hotel Requiem, the Corvins’ Tokyo Vampire Hotel. They’re planning to hunker down there as an apocalypse rages outside; they’ve selected 100 humans to breed new babies and keep their blood supply up. But there are secret tunnels under the hotel leading to Transylvania through weird twists in space; the hotel, in fact, is actually somehow within the privates of a Corvin vampire queen.

Add in flashbacks, bits of vampire lore, the internal politics of the Corvins, and occasional characterisation of the humans invited to the Corvin “coupling party” who try to fight back, and you have a goodly amount of plot even for a 142-minute movie. That’s in part because this film, written and directed by Sion Sono, is actually edited down from a 9-part TV series for Amazon that in its original form runs for about 390 minutes. So this is a two-and-a-half-hour version of a six-and-a-half-hour story. It is, as you might expect, largely incoherent.

Add in flashbacks, bits of vampire lore, the internal politics of the Corvins, and occasional characterisation of the humans invited to the Corvin “coupling party” who try to fight back, and you have a goodly amount of plot even for a 142-minute movie. That’s in part because this film, written and directed by Sion Sono, is actually edited down from a 9-part TV series for Amazon that in its original form runs for about 390 minutes. So this is a two-and-a-half-hour version of a six-and-a-half-hour story. It is, as you might expect, largely incoherent.

What you might not expect is that coherency hardly matters. It barely holds together as story, and the fights make no sense at all. But making sense is not necessarily the priority. This is fast, violent, colourful, a leading cause of the global red dye #2 shortage, and a pure sugar rush. It’s a movie all about entertaining with bloody action and only the most lurid horror imagery. As such, it does exactly what it wants to do.

That’s a little trickier than it sounds, I think. It’s not just a hyperkinetic burst of action; it has peaks and valleys, enough so you don’t get exhausted over the course of the film. It does feel shorter than 142 minutes, but then it’s also a good example of a film that won’t be to everyone’s tastes. There’s an undercurrent of sexual violence, sometimes erupting to the surface, in the way the vampires relate to the humans. There is a lot of blood. And there is a sense for most of the movie of being trapped. The Tokyo Vampire Hotel is not a place one leaves easily. A kind of claustrophobia sets in, and I think that’s deliberate; still, with all the different textures and flavours and editing issues, the tone never really sets a foot wrong.

The movie does really seem to get started once the action moves inside the hotel. The halls and rooms are painted in flat primary colours, eye-popping in a movie already filled with saturated hues. This is especially appropriate because the movie’s flat, all surface in the best way. It’s consciously artificial and gives us a setting to match: surreal in its brightness and candy-like gloss. Edits are quick, and imagery is always inventive. The movie’s first set-piece is a killer in pink machine-gunning a restaurant, and it doesn’t really slow down from there except for the occasional flashback setting up K’s romance with the leader of the Draculas.

Perhaps the most surprising thing in the film is the fact that Manami, set up to be a Chosen One protagonist, is not the hero of this story. In fact, the more she comes into her power, the more animalistic she becomes. Instead K takes centre stage, meaning her romance becomes more central to the action. In a manner of speaking; that’s what drives her, but mainly we see her in action. There’s not much in the way of profound dialogue or character development — or character at all, come to that. Alfred Hitchcock once defined drama as life with the dull bits cut out; this movie is a drama with the relatively dullest bits cut out.

It’s a mess, of course, but not as much of one as it by rights should be. The twists and big story moments come at a machine-gun pace, and that means is that if a moment doesn’t land another one’s coming along an instant later. Usually you need character to keep you engaged in a story; somehow that doesn’t apply here. K’s certainly the most involving, with a moderately tragic backstory and some reason to fight her enemies. But beyond that the Corvins are simply monsters, if effective ones, and their human victims don’t get quite enough screen time to really feel sympathetic. The conclusion feels a bit underwhelming as a result. It’s a mass brawl with gunfire and swords and all kinds of weapons, up and down stairs, with surprise characters appearing … but there isn’t really a big moment to cheer at. And this is the sort of movie that could really use something like that in its conclusion.

It’s a mess, of course, but not as much of one as it by rights should be. The twists and big story moments come at a machine-gun pace, and that means is that if a moment doesn’t land another one’s coming along an instant later. Usually you need character to keep you engaged in a story; somehow that doesn’t apply here. K’s certainly the most involving, with a moderately tragic backstory and some reason to fight her enemies. But beyond that the Corvins are simply monsters, if effective ones, and their human victims don’t get quite enough screen time to really feel sympathetic. The conclusion feels a bit underwhelming as a result. It’s a mass brawl with gunfire and swords and all kinds of weapons, up and down stairs, with surprise characters appearing … but there isn’t really a big moment to cheer at. And this is the sort of movie that could really use something like that in its conclusion.

Oddly, it struck me that the film has some interesting rules for its vampires. Everything takes pace over the course of a night, so pesky issues about daylight don’t come into play, but it gives the vampires a striking weakness in which one can burn their shadows to make them vulnerable to normal weapons. That’s a clever idea, though much else about vampire magic is left vague; how the Corvins came to build the hotel in the first place, for example, isn’t much touched on. Perhaps it’s in the extended version.

There are odd bits and pieces sticking out of the film, presumably artifacts of the editing process. Yamada’s the son of the Prime Minister of Japan, which never really comes to anything. The idea of an apocalypse going on outside of the hotel is underplayed. But, again, perhaps it’s not surprising. It’s a kind of slick psychotronic film, if that’s not a contradiction in terms. It’s about violence and blood and weird sexual undertones and bright colours and quick hypnotic editing. Is it a good film? Depends on definitions, I suppose. It’s a film that mostly does what it wants. There are things missing here, for all the ingenuity of the editing. But it contains the things it needs to contain: swordplay, gunplay, and fangs sinking into flesh.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.