Fantasia 2018, Day 19, Part 1: Cinderella the Cat

I had three films on my schedule for Monday, July 30. First, an animated science-fictional retelling of Cinderella for adults, called Cinderella the Cat. Then I’d hurry from the J.A. De Sève Theatre to the Centre Cinéma Impérial, where Fantasia was presenting a documentary from the early 80s about bandes dessinées: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? Then I’d run back to the Hall Theatre for a presentation of Sion Sono’s Tokyo Vampire Hotel, a kinetic horror-action film with campy apocalyptic overtones. Even for Fantasia, it was going to be a strange day.

I had three films on my schedule for Monday, July 30. First, an animated science-fictional retelling of Cinderella for adults, called Cinderella the Cat. Then I’d hurry from the J.A. De Sève Theatre to the Centre Cinéma Impérial, where Fantasia was presenting a documentary from the early 80s about bandes dessinées: Pourquoi l’étrange Monsieur Zolock s’intéressait-il tant à la bande dessinée? Then I’d run back to the Hall Theatre for a presentation of Sion Sono’s Tokyo Vampire Hotel, a kinetic horror-action film with campy apocalyptic overtones. Even for Fantasia, it was going to be a strange day.

Cinderella the Cat (originally Gatta Cenerentola) had less to do with the tale that inspired it than you might think. In the near future, a genius inventor’s created a ship that can create holograms and which will be the Science and Memory Hub for the city of Naples, where it is docked — for that is the home of its inventor. This man, Vittorio Basile (voice of Mariano Rigillo), has a young daughter named Mia (who is essentially mute throughout the film), and is about to marry a glamorous woman named Angelica (Maria Pia Calzone). Unfortunately, Angelica is under the thumb of a mob boss named Salvatore (Massimiliano Gallo). Vittorio ends up dead at Salvatore’s hands, and Angelica takes control of the ship. Years later, the ship’s been turned into a night-club, Vittorio’s former bodyguard Primo Genito (Alessandro Gassman) has become an undercover cop out for revenge, and Mia’s about to reach the age where she’ll take control of her inheritance — if Angelica, and Mia’s six stepsisters, don’t put an end to her first.

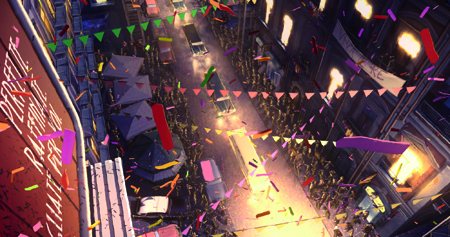

The plot’s intriguing, but what has to be said at once is that this is a beautiful film that does stunning things with light. More than that, there are ghostly holograms, fireworks, bits of ash (or cinders), always stuff moving on screen, giving texture to the images and scenes. The effects for all these things work, creating a sense of motion and shadow. Watercolours and 3D CG mix astonishingly well. Characters are animated, with expansive body language, especially Salvatore, gesturing wildly and always seeming to play to an audience whether he’s on or off stage. I will say that I didn’t get much of a sense of the ship as a place, because it holds too many environments within it — bedrooms, a stage, a broken and flooded hold, any number of corridors, on and on. It’s almost a weird lush techno-gothic castle, but sprawls a little too much. Still, the world of the film’s stylish, a noirish, shadowed place with obvious science-fictional touches but also a retro sense. It works in vaguely the same way the Dini-Timm Batman Animated Series did — using bits of past fashions and prop designs to create a setting with a reality all its own.

Tonally, though, this film’s conscious of being for adults. There’s a lot of violence, and a fair amount of sex, though nothing explicit. Salvatore sells cocaine crystallised in the shape of shoes. One of the six stepsisters has a masculine body. But the twist here is mainly that the traumatised goth Cinderella is no longer at the heart of the piece.

Tonally, though, this film’s conscious of being for adults. There’s a lot of violence, and a fair amount of sex, though nothing explicit. Salvatore sells cocaine crystallised in the shape of shoes. One of the six stepsisters has a masculine body. But the twist here is mainly that the traumatised goth Cinderella is no longer at the heart of the piece.

Cinderella the Cat is primarily a crime story with science-fictional elements. Primo Gemito is the protagonist, trying to take down Salvatore and end his criminal reign. Mia, the Cinderella figure, is significant but not central. She literally doesn’t have a voice. To an extent this can be seen as an extension of the film’s themes — the expansive Salvatore is a singer, as though he’s taken Mia’s voice, along with her power and place in the world. And there is much that I think can be read into this film about power in opposition to culture.

Researching the story around the internet, I find there are comments on Italian politics that flew over my head while watching. For example, Salvatore’s habit of taking a mike in hand and singing to the patrons of the club-ship parallels Silvio Berlusconi’s early days as a singer aboard a cruise ship. You can be ignorant of these things, as I was, and still note that there’s a sense of local particulars to the film: there’s a lot in this movie about Naples and the attempt of Naples to build itself up as a city. The characters are conscious of themselves as Neapolitans, and have a pride in their home city that inspires a lot of what they do. Vittorio wants to build his Hub of Science and Memory in his home, while Salvatore has a different vision. His songs are about Naples, and the sense of the history of the place refracted in different ways echoes the way the story of Cinderella’s remixed here; perhaps appropriate in a film partly (I think) about memory.

Salvatore, in part consciously and in part not, is trying to impose his vision of Naples on the city, while Vittorio wanted to give the city a kind of means of self-expression. Gemito’s rule of law is the only way to stop him, but can’t succeed without Mia, the daughter of the city. The first European version of the Cinderella story, published in 1634, was written in Naples, in the Neapolitan dialect, by Gaimbattista Basile (whose surname has descended to Vittorio and Mia). What better character to use to tell a story about Naples?

Salvatore, in part consciously and in part not, is trying to impose his vision of Naples on the city, while Vittorio wanted to give the city a kind of means of self-expression. Gemito’s rule of law is the only way to stop him, but can’t succeed without Mia, the daughter of the city. The first European version of the Cinderella story, published in 1634, was written in Naples, in the Neapolitan dialect, by Gaimbattista Basile (whose surname has descended to Vittorio and Mia). What better character to use to tell a story about Naples?

Except that the story feels off, a little, and I think that’s because Mia’s not as central to the story as she should be. The story, dramatically, is more concerned with Gemito’s desire to take down Salvatore versus Salvatore’s plans for power, while Vittorio’s inventions provide the backdrop for the tale. In other words, this is an oddly masculine version of the Cinderella story. Angelica’s arguably more pivotal to the tale than Mia, and in fairness is a much more well-rounded character than the typical wicked step-mother. But if the film’s well-plotted, it feels a bit odd as a version of the fairy-tale with the emphasis largely on males, as though the film was a masculine appropriation of Cinderella’s story. (While thinking along these lines, I’ll say as well that the male-bodied stepsister is clearly villainous if not, so far as I could see, with any reference to gender identity; and that there was a scene of mobsters being casually racist against minor Chinese characters. I noted these things while watching in the theatre and both came up in talking about the film afterward, so are likely worth mentioning here.)

Cinderella the Cat is a fine and eye-catching movie. It’s an interesting fairy-tale retelling that avoids obvious or gratuitous grimdark choices while still reimagining the story in a different form, with both science-fiction and crime elements baked into the structure as though natural to the tale. It’s got a strong sense of local culture informing the story, as well; I’m just not sure about the movie’s choices of which characters to focus on. I can’t help but think the film would have been more interesting if Mia had been more central, and especially if she’d had some kind of voice. It’s a movie that does a lot visually, but I don’t know that enough of Mia comes across. Still, it’s a striking movie, and an entertaining one, well worth watching. It perhaps narrowly misses out on being a great one, though; as if, despite itself, the bones of the old story still constrain the new shape of the modern film.

Cinderella the Cat is a fine and eye-catching movie. It’s an interesting fairy-tale retelling that avoids obvious or gratuitous grimdark choices while still reimagining the story in a different form, with both science-fiction and crime elements baked into the structure as though natural to the tale. It’s got a strong sense of local culture informing the story, as well; I’m just not sure about the movie’s choices of which characters to focus on. I can’t help but think the film would have been more interesting if Mia had been more central, and especially if she’d had some kind of voice. It’s a movie that does a lot visually, but I don’t know that enough of Mia comes across. Still, it’s a striking movie, and an entertaining one, well worth watching. It perhaps narrowly misses out on being a great one, though; as if, despite itself, the bones of the old story still constrain the new shape of the modern film.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Did your research reveal the nature (specifically, the item it’s shaped like) of the charm that Salvatore wears throughout? I won’t bring up my obtuse theory right now, but being sure it’s what I think it is would add ammunition for my claims at another time…

I didn’t come across anything about it one way or another. I like your theory, though, It fits with Salvatore’s theatricality …