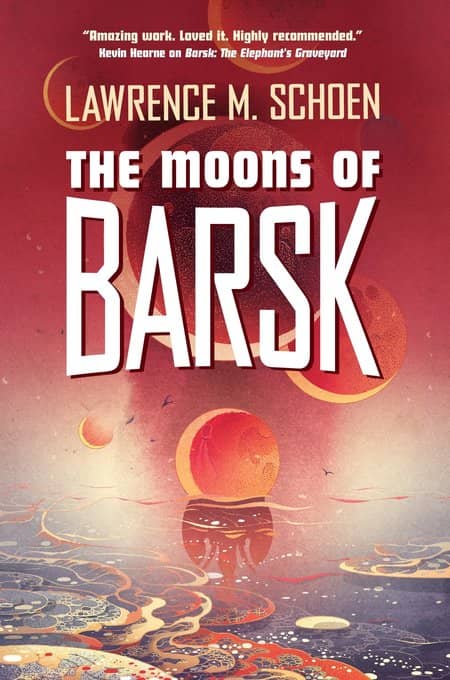

Future Treasures: The Moons of Barsk by Lawrence M. Schoen

|

|

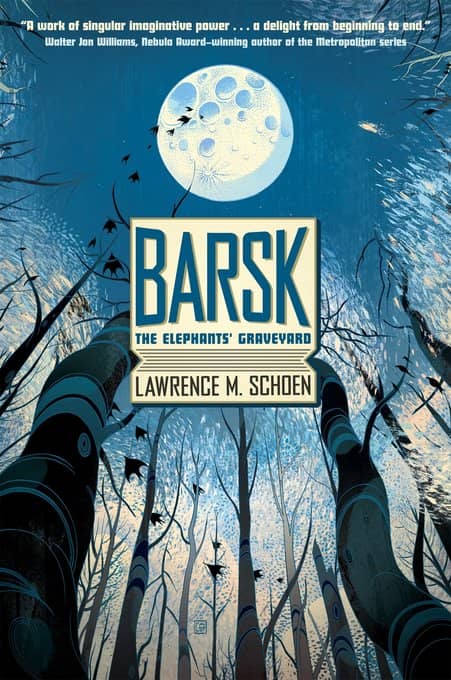

Lawrence M. Schoen’s novel Barsk: The Elephants’ Graveyard was nominated for a Nebula Award, and Nancy Hightower at The Washington Post gave it a concise and enthusiastic review, saying:

Barsk is set 62,000 years into a human-less future, where anthropomorphic animals rule the galaxy. There is no record of human existence, and while the different species get along relatively well, the Fant, an elephant-like hybrid, are completely shunned and exiled to live on a rainy planet called Barsk. While labeled less intelligent and “dirty,” the Fant nonetheless are the only species to produce a drug that allows clairvoyants known as Speakers to commune with the dead. When the planet is threatened with invasion and annihilation by the galaxy Senate, Jorl, a Fant Speaker, must race to save it by communing with ancient beings who hold even darker truths. Suspenseful and emotionally engaging, Barsk brings readers into a fascinating speculative world.

It was widely praised in the genre. Walter Jon Williams called it “a work of singular imaginative power,” and Karl Schroeder proclaimed it “a compulsive page-turner and immensely enjoyable.”

I’ve been looking forward to the sequel, and I’m not the only one. It was selected as one of the the Best Sci-Fi and Fantasy Books of August 2018 by both Unbound Worlds and the Barnes & Noble Sci-Fi 7 Fantasy Blog; the latter said, “With a cast of uplifted animals of all stripes and unparalleled worldbuilding, this series is a sorely under-appreciated, highly original delight.” It arrives in hardcover next week from Tor.

My third movie on Sunday, July 15, was a France-UK co-production called Cold Skin. It was scheduled to start at 5:10 in the Hall Theatre, and ran 107 minutes. At 7:15, across the street at the De Sève, there’d be a showing of the 1911 Italian film L’Inferno, an adaptation of the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Musical accompaniment to the silent film would be provided by Maurizio Guarini of Italian prog band Goblin, well-known for providing the soundtrack to Dario Argento’s

My third movie on Sunday, July 15, was a France-UK co-production called Cold Skin. It was scheduled to start at 5:10 in the Hall Theatre, and ran 107 minutes. At 7:15, across the street at the De Sève, there’d be a showing of the 1911 Italian film L’Inferno, an adaptation of the first part of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Musical accompaniment to the silent film would be provided by Maurizio Guarini of Italian prog band Goblin, well-known for providing the soundtrack to Dario Argento’s

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.