Fantasia 2018, Day 17, Part 2: Punk Samurai Slash Down

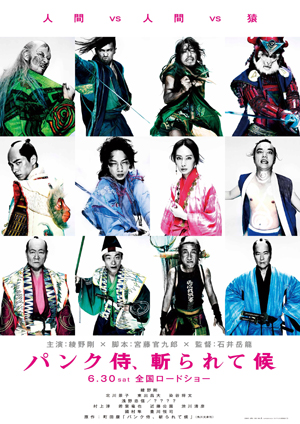

The last movie I saw on Saturday, July 28, was at the Hall Theatre. It was Punk Samurai Slash Down (Panku Samurai Kirarete Soro, パンク侍、斬られて候), an adaptation of Ko Machida’s 2004 novel directed by Gakuryu Ishii and scripted by Kankuro Kodo (who also wrote Too Young To Die!). It’s a period story about a wandering samurai, Junoshin Kake (Go Ayano, also at Fantasia this year as Sato in Ajin: Demi-Human), who concocts a scheme to get himself hired as a retainer of the Kurokaze Han noble house. He kills an old man, and convinces one faction of the Kurokaze Han, led by Shuzen Oura (veteran Jun Kunimura, whose string of credits include The Wailing as well as this year’s Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura) that the dead man was an agent of a suppressed group of heretics called the Belly-Shaking cult. The cult believes that the world has been eaten by a gigantic tapeworm. The ideal is to be excreted from the tapeworm, which is brought about by shaking the belly. But the contempt for the world also has led the cult to massive rioting and cruel criminal acts in the past; the spectre of their revival is terrifying — until it turns out to be false, and Kake’s threatened with execution. Unless he can prove himself “innocent” by secretly bringing the cult into existence, which would also enhance the credibility of Oura’s political faction. He sets out to create the threat he’s warned against, and things rapidly spiral out of control.

The last movie I saw on Saturday, July 28, was at the Hall Theatre. It was Punk Samurai Slash Down (Panku Samurai Kirarete Soro, パンク侍、斬られて候), an adaptation of Ko Machida’s 2004 novel directed by Gakuryu Ishii and scripted by Kankuro Kodo (who also wrote Too Young To Die!). It’s a period story about a wandering samurai, Junoshin Kake (Go Ayano, also at Fantasia this year as Sato in Ajin: Demi-Human), who concocts a scheme to get himself hired as a retainer of the Kurokaze Han noble house. He kills an old man, and convinces one faction of the Kurokaze Han, led by Shuzen Oura (veteran Jun Kunimura, whose string of credits include The Wailing as well as this year’s Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura) that the dead man was an agent of a suppressed group of heretics called the Belly-Shaking cult. The cult believes that the world has been eaten by a gigantic tapeworm. The ideal is to be excreted from the tapeworm, which is brought about by shaking the belly. But the contempt for the world also has led the cult to massive rioting and cruel criminal acts in the past; the spectre of their revival is terrifying — until it turns out to be false, and Kake’s threatened with execution. Unless he can prove himself “innocent” by secretly bringing the cult into existence, which would also enhance the credibility of Oura’s political faction. He sets out to create the threat he’s warned against, and things rapidly spiral out of control.

This is a very odd movie; it doesn’t simply begin strangely, but continually increase its oddness at each point when you think you’ve begun to assimilate what it’s doing. The scale increases, as well, as the Belly-Shaker cult grows beyond all expectation and a wholly unexpected other faction emerges. Ultimately the film ends in a cosmic battle of thousands of samurai and their allies against the Belly-Shaker cult, and perhaps it’s a mark of success that the large-scale battle scene never overwhelms the satirical tone of the film but ends up supporting it. Without actually being Gilliam-like there’s a bit of a feel to the ending of a Gilliam movie, wild exuberance petering out into a knowing anti-climax.

There is a range of tones to the movie, though, and Kake is enough of a coherent character to engage an audience. Conversely, there’s a narrator (Masatoshi Nagase) telling the story in part through voice-over, providing another perspective; eventually we find out who this seemingly-omniscient narrator is, and learn he’s actually embedded in the story. Nobody’s above the fray, nobody’s out of the world of the film — even those trying to get themselves out of the world entirely. The gnostic leanings of the Belly-Shaker cult feel something out of a Philip K. Dick story, a paranoiac danger that might actually understand reality better than anyone would like. Except they’re the villains; and except that the nominal heroes aren’t heroic either, as the first thing we see Kake do is kill a man in cold blood. Ayano’s charismatic enough that we tend to forget this enough to accept him as a protagonist, but the movie doesn’t. (And this does come back to him in a telegraphed bit of poetic justice.)

The movie finds a balance in its approach, I think, between constructing a story that’s engaging and also satirising that story and the world it imagines. There’s enough of a linear narrative that it’s involving. And enough questioning of the narrative, more and more as it goes along, that there’s some satisfaction there as well. We feel enough for the characters to be affected by occasional touching moments — as when Oura’s rival Tatewaki Naito (Etsushi Toyokawa, also in Laplace’s Witch) finds a surprising peace in a provincial puppet theatre, attached to a pet monkey. But the cynical ending of the film doesn’t come as a surprise or a disappointment. We’re set up to know roughly how the film’s going to end. You get out of the world, or you see it all end in disappointment.

The movie finds a balance in its approach, I think, between constructing a story that’s engaging and also satirising that story and the world it imagines. There’s enough of a linear narrative that it’s involving. And enough questioning of the narrative, more and more as it goes along, that there’s some satisfaction there as well. We feel enough for the characters to be affected by occasional touching moments — as when Oura’s rival Tatewaki Naito (Etsushi Toyokawa, also in Laplace’s Witch) finds a surprising peace in a provincial puppet theatre, attached to a pet monkey. But the cynical ending of the film doesn’t come as a surprise or a disappointment. We’re set up to know roughly how the film’s going to end. You get out of the world, or you see it all end in disappointment.

Still, if it’s a witty movie, it’s also wearying. It’s 130 minutes long, and if it packs that running time with a twisting plot, that also means it’s very busy. The story keeps expanding, adding new elements like a telekinetic messenger (Ryûya Wakaba) and a superskilled assassin (Jun Murakami). The eclectic cinematic techniques — flashbacks and freeze-frames and even the narration — add to the kinetic feel of the film, and if that’s not usually a bad thing, it’s also possible to have too much of even a good thing.

Overall, though, the movie’s ironic tone toward politics and status-seeking comes through. Kake doesn’t get into many fights. He’s much more of a con-man than a standard knight or even standard bully. His story is one of scheming, not one of swordfighting. And the scheming’s not for anyone’s benefit but his own. That’s fine; the same’s true of the other political figures. The Belly-Shakers have an ideal, but it’s a terrible one. The best characters in this movie aren’t human. “The world doesn’t make sense anyway,” we’re told late in the film, and it is, in all, hard to disagree.

This is a good movie that sometimes seems to be twisting its way along without much of a sense of direction, but which does pull itself together for a credible ending, however ragged and surreal. It’s entertaining moment-to-moment; no slow build here. There is a definite punk energy informing the thing, but with a consciousness of craft that’s alien to punk. There’s less a hostile sense of anger than a kind of bleeding-heart cynicism. It is, in all, quite strange. Is it a success? It’s engaging in the theatre, but I was left nonplussed at the end, and I’m not sure whether its ambitions quite match its accomplishment. I wasn’t disappointed, though, and I saw some new things I never expected to see. It’s audacious, sprawling, and occasionally bizarre; and it knows what it is. I may need another viewing to assimilate it properly, but, and this is what it comes down to, I’d like to get that second viewing if I have the chance.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.