Fantasia 2018, Day 17, Part 1: Laughing Under the Clouds and the 2018 Afromentum Showcase

Saturday, July 28, saw me arrive at the Hall Theatre early for a showing of the Japanese historical fantasy Laughing Under the Clouds, yet another manga adaptation. Following that, I’d head across the street to the J.A. De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch a short film showcase called Afromentum. It’d feature four short films by Black filmmakers from around the world — including an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto.”

Saturday, July 28, saw me arrive at the Hall Theatre early for a showing of the Japanese historical fantasy Laughing Under the Clouds, yet another manga adaptation. Following that, I’d head across the street to the J.A. De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch a short film showcase called Afromentum. It’d feature four short films by Black filmmakers from around the world — including an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto.”

Laughing Under the Clouds (Donten ni warau, 曇天に笑う) was directed by Katsuyuki Motohiro, whose excellent adaptation Ajin: Demi-Human I’d just seen the evening before. The script was written by Yûya Takahashi from the manga by Kemuri Karakara. In the 19th century, a trio of brothers in a Japanese village guard against the return of a terrible dragon. The eldest, Tenka Kumo (Sota Fukushi) is a highly-skilled fighter; his younger brother Soramaru (Yuma Nakayama) is nowhere near as good; the third, Chutaro (Kirato Wakayama) is just a child. But agents of the dragon are at work, and the creature will rise soon. Can the Kumos stand against it?

This is a disappointing movie. After seeing Ajin I had great respect for Motohiro’s skills, and I’d appreciated Fukushi’s work in other movies this year: The Travelling Cat Chronicles, Bleach, and Laplace’s Witch. But things don’t come together here. There are some very nice moments, including a splashy opening scene, but this movie doesn’t work as a whole. The characters are unconvincing, it tries to fit too much into a 94-minute running time, and the conclusion’s an extended anti-climax.

The problem, I think, comes from the core trio of brothers, and the way the movie envisions them. Soramaru’s interesting because he’s fallible in a way that Tenka isn’t, but it’s not clear why he isn’t as good a fighter as Tenka if Tenka’s been teaching him. This power difference drives the plot. The ages of the characters aren’t stated, but there’s only a year difference between the two actors, and Nakayama certainly looks like an adult in his early 20s — shouldn’t he be at least close to Tenka in skill? But he isn’t, and he’s frustrated, and so at one point he abandons his brothers to go train with a group of government agents who are rivals to the Kumos. The stakes of the rivalry seem petty next to the danger of the dragon, though, so this never really feels especially dramatic.

Fukushi, meanwhile, tries his hardest. “Our family’s role is to restore laughter to the world!” we’re told once; but if Tenka’s the only one laughing much of the time, he comes off less as jovial and more as slightly demented. Fukushi’s a genuinely charismatic actor, but here it’s as if he’s too charismatic, taking up too much of the screen with a character that isn’t written as especially interesting. There’s a minor character, Shirasu Kinjo (Renn Kiriyama) who lives with the Kentos and who perhaps was meant to have been more significant; as it is, events involving him late in the story feel weightless.

Fukushi, meanwhile, tries his hardest. “Our family’s role is to restore laughter to the world!” we’re told once; but if Tenka’s the only one laughing much of the time, he comes off less as jovial and more as slightly demented. Fukushi’s a genuinely charismatic actor, but here it’s as if he’s too charismatic, taking up too much of the screen with a character that isn’t written as especially interesting. There’s a minor character, Shirasu Kinjo (Renn Kiriyama) who lives with the Kentos and who perhaps was meant to have been more significant; as it is, events involving him late in the story feel weightless.

The world’s baffling as well. An island filled with prisoners sentenced to hard labour for the rest of their lives at first seems like an interesting way to muddy the moral waters — the message is apparently that the government the heroes are striving to protect is capable of great evil itself in the name of righteousness. This completely fails to come up again in the film, and the island of prisoners ends up being used in a much more mundane plot twist.

It is entirely possible that this film is simply too short. There are a lot of characters here, especially once the squad of government soldiers enters the picture. We never really get a good sense of them, or of the backstory their leader has with Tenka. Just as we don’t really get a sense of the backstory and friendship of Tenka with Kinjo. All these characters have a role to play in the story, but they don’t really come off as more than plot elements. There’s no room to breathe for any of them, no pleasant character moment that also reveals who they are on a deep level.

There’s also not much humour, which is surprising for a movie titled Laughing Under the Clouds. Nor is there really the greyness the phrase suggests. Tenka’s perpetual smile doesn’t feel like an act of will or determination to keep a family tradition going. It’s simply there. It’s as close to a theme as I could find in the film, which otherwise feels almost determined to be empty of meaningful subtext.

There’s also not much humour, which is surprising for a movie titled Laughing Under the Clouds. Nor is there really the greyness the phrase suggests. Tenka’s perpetual smile doesn’t feel like an act of will or determination to keep a family tradition going. It’s simply there. It’s as close to a theme as I could find in the film, which otherwise feels almost determined to be empty of meaningful subtext.

Still, there are nice moments in the film. The fights are good, with a naturalistic choreography. The special effects work, and if the structure of the climax is dramatically inert, at least it’s nice to look at. There’s a reasonable sense of threat in the background, building through the film. Unfortunately, the characters in the foreground aren’t terribly involving.

This is an oddly dark film, not tonally, but visually. That’s not so much due to any sophisticated use of shadows so much as a general dullness. And that strikes me as odd since many of the characters wear extravagant and colourful costumes. There’s an incipient clash of tones here, a weird mix of the everyday with the heightened world of a fantasy. I would say that there’s too little of the latter; in a story about dragons and mystic warriors, there’s too little movement beyond the real. Soramaru’s resentment of Tenka and desire to become a better fighter makes sense in terms of his character, but is too slender a reed to bear the weight of the whole film. Yet there’s little tension to the movie beyond that. As I say, there are good things and good elements here. I have no problem believing that the original is much more involving. But it certainly seems that some bad choices were made in the process of adapting the story to film. If it’s never especially bad, it’s also rarely engaging.

Across the street, the Afromentum Showcase followed. There were four films, two animated, from four different countries. They made for an intriguing mix.

Across the street, the Afromentum Showcase followed. There were four films, two animated, from four different countries. They made for an intriguing mix.

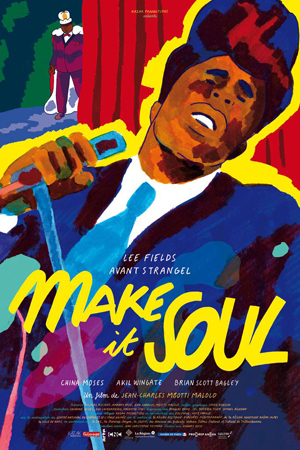

First came “Make It Soul,” directed by Parisian Jean-Charles Mbotti Malolo from a script he wrote with Amaury Ovise and Nicolas Pleskof. It’s an animated film about a night in 1965 when Solomon Burke (voice of Avant Strangel), a singer who bills himself as the King of Rock and Soul, goes to Chicago to be crowned yet again, this time by a hungry, ambitious young performer (Lee Fields). What Burke does not know is that this singer has plans of his own, and this night will mark the moment the role of king is handed to the rising star James Brown.

This is a dramatised account of a night that really happened, and it’s a beautiful piece to look at. The animation’s expressionistic and richly coloured, yet far from psychedelic (I’m told it’s inspired by African-American folk art). There’s a sense of the place and the time, a feel of what dressing rooms and backstage feel like and sound like; the sound design captures music not only in its full glory from the audience but also the echoes you hear off to the stage or from the other side of a wall. The characters are designed splendidly, not caricatures but expressive, moving expressively and in one case … well, so far as I can see, moving like James Brown.

There is maybe one genre of music I’m competent to write about, and soul is not it (the genre in question will be coming up in a couple of movies later on in the festival, though). But even for someone as ignorant of the form as I am, the meaning of the night and at least to an extent the feel of the music come through. It’s a touching and complex film; one feels for the old king even as the excitement of his dethronement is palpable. And the background of the mid-60s, the social consciousness, is subtly present in the background to flavour events even further.

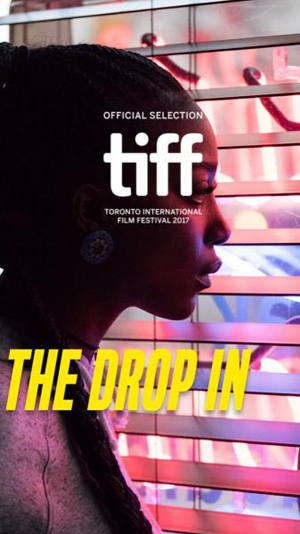

Next was “The Drop In,” by Torontonian writer-director Naledi Jackson. A hairstylist, Joelle (Mouna Traoré), is closing up shop. A businesswoman, Grace (Oluniké Adeliyi), begs her to stay open, to do her hair before locking up. Joelle reluctantly agrees — only to find that Grace knows a secret about her, and has quite another reason for coming to her shop.

At only 13 minutes long, it’s difficult to say too much about the short without giving the twists away. I can say that it begins with a brooding feel, shadowed and textured, and then after a science-fictional twist becomes a more overt conflict. It’s played well, and leaves questions open at the end in a good way. We don’t need more details than we get; we understand, roughly, what the characters are fighting for. It’s played well, and looks sharp all the way through.

At only 13 minutes long, it’s difficult to say too much about the short without giving the twists away. I can say that it begins with a brooding feel, shadowed and textured, and then after a science-fictional twist becomes a more overt conflict. It’s played well, and leaves questions open at the end in a good way. We don’t need more details than we get; we understand, roughly, what the characters are fighting for. It’s played well, and looks sharp all the way through.

The third film was one of the pieces I’d been looking forward to all festival. In 2016 I saw and greatly enjoyed Battledream Chronicles, an animated YA dystopia from Martinique by director and animator Alain Bidard. This year saw a reimagining of Bidard’s concept, “Battledream Chronicles: A New Beginning.” It’s a reboot of the feature as an animated series, and we saw the first half-hour (well, 24-minute) episode. Much is similar: as in the original, imperialist slavers are exploiting and enslaving other nations, forcing them to toil inside a virtual-reality game. Syanna’s one of the slaves, waking up with her memory wiped to find she must gather 500 points a day or die. But there are hints of a deeper game, and Syanna and her friends follow a mysterious path, hoping to find a better life. (I can’t find detailed cast information online; the festival site lists Nuriyyih Gerrard, Alison Hinds, Joseph Marcell, and Nickolai Salcedo as the voice actors.)

But there are differences. This story’s set earlier in Syanna’s career, when she’s young and just starting out in the game. It’s an inspired choice. As a season-long series, the story can take its time in a way the film can’t, and show us Syanna growing into her role. More than that, the characters have more interesting visual designs. One of the few criticisms I had of the original Battledream was that all the female characters had the same general body type. That’s definitely not the case here. People are different ages, and they have different builds. And they have very different personalities. The group of youths Syanna ends up exploring with each look different, and each sound different — each has a different accent (a friend of mine tells me that they’re each done very well, too, so you can tell at once which island each character’s from, even down to the way one of them sucks his teeth).

We got to see only one chapter of the series, so the conclusion was a bit abrupt. But what we did see makes me very interested in seeing more. The same use of YA tropes with a powerful political awareness informing them is present, and the mysteries are new and expansive. The same excellent realistic animation style is present. The anger and despair of Syanna comes across powerfully, as do the faint flickers of hope. A subplot showing dissension in the ranks of the masters is intriguing. The show I saw is an excellent introduction, and I hope I get to see the rest of it at some point.

Finally came “Hello, Rain,” a 30-minute film from Nigerian writer-director C.J. Obasi (whose Ojuju I saw in 2015). It’s an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto,” and it begins with a woman, Rain (Keira Hewatch), trying to right a wrong. She invented powerful wigs through a fusion of magic and technology, and they turned two other women, Philo (Tunde Aladese) and Coco (Ogee Nelson), into goddesses. Now they’re rampaging, destroying lives without a care. But Rain thinks she has a plan to stop them.

Finally came “Hello, Rain,” a 30-minute film from Nigerian writer-director C.J. Obasi (whose Ojuju I saw in 2015). It’s an adaptation of Nnedi Okorafor’s short story “Hello, Moto,” and it begins with a woman, Rain (Keira Hewatch), trying to right a wrong. She invented powerful wigs through a fusion of magic and technology, and they turned two other women, Philo (Tunde Aladese) and Coco (Ogee Nelson), into goddesses. Now they’re rampaging, destroying lives without a care. But Rain thinks she has a plan to stop them.

The story’s told in three parts, each narrated by one of the women. The pacing’s slow, but works. The story comes out, we see the destruction, we see Rain’s attempt to stop it. The art direction’s striking, with each character given a dominant colour. That plays out in costume, make-up, and setting. Beyond that, though, I found the aesthetic hard to wrap my mind around. The special effects are plentiful but (I think deliberately) cheap. I don’t mind that at all (I grew up on old-school Doctor Who), but the sound effects for some of the high-tech effects are very clearly reused from another source. I also found Hewatch’s voice-over flat.

There’s a very distinct vision at work in this film, and I’m not sure that I’m not missing the point. A friend of mine, more knowledgeable about the culture on screen, was able to pick up on things I couldn’t — the way a purse was used, for example. This is a film that was given a special mention by the festival jury, citing its “spiritually fueled universe.” I can see why. It’s ambitious and confident. I couldn’t find a way to be pulled into it. But I wouldn’t mind seeing it again.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.