Fantasia 2018, Day 16: The Witch in the Window and Ajin: Demi-Human

I had two movies to see on Friday, July 29. The first, perfectly fitting the small De Sève Theatre, was The Witch in the Window, a quiet character-centred horror film. The second was another live-action manga adaptation, Ajin: Demi-Human, a fast-paced explosion-oriented semi-super-hero story which fit the larger Hall Theatre as well as The Witch in the Window suited the De Sève. I had certain hopes for both, and in both cases those hopes were wildly exceeded. These are two excellent movies, of very different kinds.

I had two movies to see on Friday, July 29. The first, perfectly fitting the small De Sève Theatre, was The Witch in the Window, a quiet character-centred horror film. The second was another live-action manga adaptation, Ajin: Demi-Human, a fast-paced explosion-oriented semi-super-hero story which fit the larger Hall Theatre as well as The Witch in the Window suited the De Sève. I had certain hopes for both, and in both cases those hopes were wildly exceeded. These are two excellent movies, of very different kinds.

The Witch in the Window is written and directed by Andy Mitton, whose very fine film We Go On I saw two years ago at Fantasia. Like that movie, this is a humanistic and even warm horror film, a personal meditation on fear and death. The Witch In the Window follows Simon (Alex Draper), a divorced father who has bought a house in the Vermont countryside; he plans to fix it up and flip it for a profit. To help him make over the house he brings along his son, 12-year-old Finn (Charlie Tacker). Finn recently slipped his mother’s control online and saw something deeply disturbing, so Simon hopes to bond with him as they work on the house. Finn’s less interested in this, but in any case Simon’s plans have an unexpected complication: the house is, allegedly, haunted, by an old woman who was a previous occupant and died staring out an upper window. As the two work on the house, the presence in the house becomes impossible to ignore. Can either escape the witchery of the spirit?

This is very much a classic haunted house movie, with a definite old-fashioned (but intensely effective) approach. There are no jump scares. There is no gore whatsoever. We are frightened for these characters because we are frightened for these characters. We know them, we care about them, we don’t want to see horror-movie things happen to them. It takes a certain kind of self-assuredness to try to make that sort of horror film, I think, and here it pays off. This is a movie that dares to bring the traditional haunted-house story into the modern day. It doesn’t shy away from cell phones and the internet — in fact, a cell phone’s central to one of the film’s spookiest moments. The movie’s not afraid of the modern world, which is something it embraces in its story, something resonant with its themes: the refurbishing of the old, the evocation and transformation of a spirit.

Note that the cinematography’s accordingly excellent, as it must be: atmospheric yet precise, establishing both age and technology as needed, old wood and power tools and portable lights. There’s a sense of the architecture of the house, of its layout, of its narrowness and shadows. There’s a sense of the forested grounds around it, warm and green yet isolating. The sunlight of Vermont, its moods and angles, is captured so well as to almost be another character. The framing’s unobtrusively correct; the film grammar here is as knowing in its tones as the prose of an M. R. James story. This is a movie confident enough to let some of its most frightening moments (especially early on) happen without drawing attention to them. If you’re observant, you’ll notice certain things in the frame that the characters do not, and as they play out the scene oblivious to the horror watching them the tension grows, and you can only wait, and wait, and wait.

But all the atmosphere and style and craft would mean very little without a strong script at the centre, and this sort of story wouldn’t work without strong characters. Those things are here in spades. Both leads are written well and played well. Tacker’s Finn is an excellent depiction of a kid’s mix of uncertainty and self-assurance. Draper’s Simon is an older version of that — you can see a similarity of behaviour between father and son, which is a nice touch. Draper plays Simon as both certain about his plans and deeply aware of his incapacities. The film begins with a passive-aggressive spat between Simon and his ex-wife Beverly (Arija Bareikis) about Finn: “You tell me,” she challenges, “what am I supposed to say to a little boy?” And Simon answers “I don’t know. You’re right. I don’t know.” Simon’s face to face, here and throughout the film, with what he doesn’t know about raising a child. He’s sympathetic because he can admit it.

But all the atmosphere and style and craft would mean very little without a strong script at the centre, and this sort of story wouldn’t work without strong characters. Those things are here in spades. Both leads are written well and played well. Tacker’s Finn is an excellent depiction of a kid’s mix of uncertainty and self-assurance. Draper’s Simon is an older version of that — you can see a similarity of behaviour between father and son, which is a nice touch. Draper plays Simon as both certain about his plans and deeply aware of his incapacities. The film begins with a passive-aggressive spat between Simon and his ex-wife Beverly (Arija Bareikis) about Finn: “You tell me,” she challenges, “what am I supposed to say to a little boy?” And Simon answers “I don’t know. You’re right. I don’t know.” Simon’s face to face, here and throughout the film, with what he doesn’t know about raising a child. He’s sympathetic because he can admit it.

For whatever he doesn’t know, he’s still in the role of adult, which (as a non-parent) I find an older person often adopts and perhaps must adopt when around a child. A very young person, like Finn, will not know certain things about the world and will not know how to parse some of the new knowledge that comes along. An older person, like Simon, will not have all those things worked out — but will know a few things about a few things, which might help or might not. Part of the movie’s about Simon and Finn finding out what each knows that can help the other. (I will note, incidentally, that the troubling imagery Finn finds online is not sexual in nature, and I think that’s a good choice; he found disturbingly violent material, and his reaction I think plays to some of the main themes of the movie.)

I think there’s a lot of honesty in this film about a father raising a son, and about what the father can do and what he can’t. I think, I don’t know; I don’t have the experience, thankfully. But certain lines in this film feel like hard-won wisdom. There is talk here about protection and incapacity, about lies and responsibility, and so much of it feels like good writing won through tough experience and meditation upon that experience. “I don’t know how to make him safe,” Simon confesses at one point, and that’s a line that resonates with its openness. There’s something honest in this movie, in its portrayal of Simon and of Simon’s love for Finn.

I think there’s a lot of honesty in this film about a father raising a son, and about what the father can do and what he can’t. I think, I don’t know; I don’t have the experience, thankfully. But certain lines in this film feel like hard-won wisdom. There is talk here about protection and incapacity, about lies and responsibility, and so much of it feels like good writing won through tough experience and meditation upon that experience. “I don’t know how to make him safe,” Simon confesses at one point, and that’s a line that resonates with its openness. There’s something honest in this movie, in its portrayal of Simon and of Simon’s love for Finn.

This is, in essence, a story about salvation through non-toxic masculinity. This is about Simon recognising Finn’s individuality and agency (and, later, recognising the same things in Beverly) while at the same time trying to understand what it means to be his father. This is a story about a father literally trying to build a home for his family (while, in a remarkably clever idea that’s underplayed throughout the film, his renovating the house only makes the spirit within it stronger). It’s a story about a man realising when he’s wrong and trying to fix things. It’s a story about a man determined to finish the job he begun, a problematic job at first but one that changes with his own acceptance of reality and the reality of others.

I’ll admit to being surprised that a movie titled The Witch in the Window, and about an old house in Vermont, does not in fact have a witch window in it. Still, that’s hardly a necessity, and in general this is a very well-thought-through film. It uses an excellent genre structure to get at deep and abiding themes, with a specific interest in how those themes play out in the present day. Actors do a great job with a remarkable script, and sensitive direction uses stunning cinematography to get at place and architecture — which last is central to the story. This is an excellent film about fathers and sons (in a much deeper sense than is normal in American films), about uncertainty and capability, and about learning to live with the limits of what you can do.

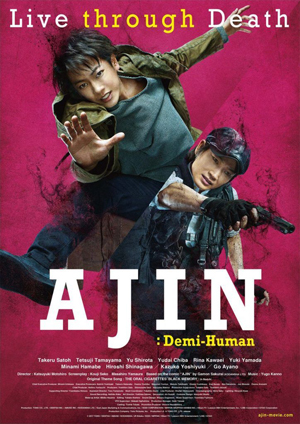

Several hours later (after returning home and then coming back downtown again) I settled in to watch Ajn: Demi-Human (Also Ajin, 亜人). Directed by Katsuyuki Motohiro from a script by Masahiro Yamaura and Hiroshi Seko based on the manga by Gamon Sakurai, it follows Kei Nagai (Takeru Satoh, of Inuyashiki, If Cats Disappeared From the World, and the Rurouni Kenshin films), a young man who discovers he’s not really human. In the near future a very few human beings turn out to be Ajin, immortal entities who heal from any injury and can create “ghosts” out of themselves, avatars visible only to themselves and other Ajin. There are 46 known Ajin in the world, and Kei’s the third in Japan. Held prisoner by the government and experimented on, he’s freed in a running gunfight by the forces of Sato (Go Ayano), the first Ajin. But Sato’s got deeper and far more violent plans, and Kei must join with the humans who tortured him to stop the maniac.

Several hours later (after returning home and then coming back downtown again) I settled in to watch Ajn: Demi-Human (Also Ajin, 亜人). Directed by Katsuyuki Motohiro from a script by Masahiro Yamaura and Hiroshi Seko based on the manga by Gamon Sakurai, it follows Kei Nagai (Takeru Satoh, of Inuyashiki, If Cats Disappeared From the World, and the Rurouni Kenshin films), a young man who discovers he’s not really human. In the near future a very few human beings turn out to be Ajin, immortal entities who heal from any injury and can create “ghosts” out of themselves, avatars visible only to themselves and other Ajin. There are 46 known Ajin in the world, and Kei’s the third in Japan. Held prisoner by the government and experimented on, he’s freed in a running gunfight by the forces of Sato (Go Ayano), the first Ajin. But Sato’s got deeper and far more violent plans, and Kei must join with the humans who tortured him to stop the maniac.

This is a clever film with clever choreography and a clever use of the Ajins’ powers. Their power sets are limited and largely duplicate each other; but what you see here is that different characters exploit their powers differently. And some are better at hiding their Ajin status than others. If, as is usual with super-hero stories, powers represent character, then we see here a different example of what that means: your character defines how you define your powers. How you think about what you can do, and the different ways you exercise your power. Sato in particular is utterly ruthless in the way he uses his power to fight and be resurrected; in a gunfight he shoots through himself, for example, and the final confrontation is set up by an unusual way of crossing distances.

All this sort of thing is more remarkable because the Ajins share quite a lot in common, in character terms. They’re all detached from humanity, lacking in empathy. They’re not human and at an instinctive level are aware of that. Sato’s irreverent attitude to his own body follows logically. Kei’s involvement with the human world is different, though, deriving from his own history, and so makes sense from his perspective. The low-empathy aspect of the Ajins runs the risk of making them difficult for an audience to empathise with, but I think it’s dramatised well. The pace of the movie perhaps helps here, as we find ourselves engaging with the characters just because of the role they play in the story — protagonist, antagonist — without worrying too much about the depths of their emotions.

At the same time, it’s possible to see deeper themes in the story. The Ajin are exploited by human governments; Sato was driven mad by experiments carried out on him. There’s a healthy distrust of authority, then, but also a sympathy with the marginalised and exploited. Of course, the metaphor runs the risk of collapsing: the Ajin have powers that do make them a threat to humans, and in fact aren’t actually human themselves.

At the same time, it’s possible to see deeper themes in the story. The Ajin are exploited by human governments; Sato was driven mad by experiments carried out on him. There’s a healthy distrust of authority, then, but also a sympathy with the marginalised and exploited. Of course, the metaphor runs the risk of collapsing: the Ajin have powers that do make them a threat to humans, and in fact aren’t actually human themselves.

Does this sound familiar? There is very definitely a level in which this story feels like a take on The X-Men: a young member of a persecuted super-powered minority fights a more extreme mastermind in the name of saving a world that hates and fears them, despite a government program bent on exploiting and exterminating their people. It’s not derivative, I think, so much as a response to the Marvel series that pushes the ideas there in a different direction. (Given how much time the X-Men spent running around Japan in the 1980s, that’s more than fair for a manga series.) The powers are on a smaller scale, giving the story a different feel; the Ajin aren’t so far above human technology. Bullets won’t kill them, but tranquiliser darts will put them to sleep — unless they kill themselves before the sedative kicks in, in which case they’re instantly reborn entirely healed and thus with the sedative purged from their body. The tactics are thought through and make for a nice twist on the usual gunfight.

The overall plot does come down to a chase for a MacGuffin, as Sato tries to capture an experimental nerve gas to use in a plan to destroy Tokyo. There’s a character-based explanation for this, but it does feel like an obvious structural move; not forced, exactly, but conventional in a way the rest of the film largely avoids. Then again, one of the few aspects of the film that does feel like something of a misstep is a subplot about Kei finding refuge with an older woman who sees him as a replacement for a son of her own; the pacing’s off, and hints of a mob attacking her house are inconsistent — an image of people gathering at night is followed by an attack in the day hours later.

Otherwise, the interaction of the various schemes make for a solid story. There’s a surprising moment in the middle when one of Sato’s plans results in a series of visuals extremely reminiscent of some of the footage from 9/11; it’s something almost shocking, imagery you simply would not see in an American film, and I think it serves a purpose beyond establishing his villainy. It puts him in the context of someone who has a specific ideology he values far above human life. (It also, incidentally, makes one reflect that the attacks happened half a generation ago, and to wonder why they haven’t been assimilated into popular culture the way other horrific images have.) It emphasises the film as having to do with political struggles, if only on a dreamlike level. Bad actions come back to haunt a government losing control.

Otherwise, the interaction of the various schemes make for a solid story. There’s a surprising moment in the middle when one of Sato’s plans results in a series of visuals extremely reminiscent of some of the footage from 9/11; it’s something almost shocking, imagery you simply would not see in an American film, and I think it serves a purpose beyond establishing his villainy. It puts him in the context of someone who has a specific ideology he values far above human life. (It also, incidentally, makes one reflect that the attacks happened half a generation ago, and to wonder why they haven’t been assimilated into popular culture the way other horrific images have.) It emphasises the film as having to do with political struggles, if only on a dreamlike level. Bad actions come back to haunt a government losing control.

Ajin: Demi-Human is a confident film, I think. It moves quickly, builds well, and has a solid structure. We’re dropped right into the story from the opening frames, and things keep going from there through a series of twists and revelations. If the build-up to the final confrontation’s a little programmatic, the battles of that last part of the film are solid. This is an excellent super-hero action film, assured, eventful, and engaging.

Two movies for me on the day; two very different kinds of films. Both excellent. It’s a fine thing when a day works out so well.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.