Tolkien Manuscripts and Artwork On Display in Oxford

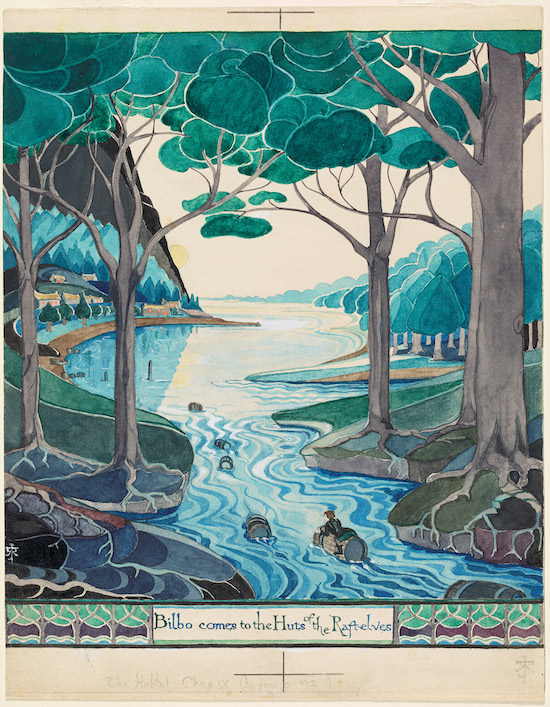

Bilbo comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves, a watercolor Tolkien

painted for the first edition of The Hobbit, published in 1937.

Bilbo is seen sitting astride a barrel floating down the forest river,

having helped the dwarves (who are hidden inside the wine barrels) to

escape from the dungeons of the Elvenking. This was Tolkien’s favorite

watercolor and he was disappointed to find that it had been omitted from

the first American edition. Credit: © The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937.

The University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library has launched the largest exhibition on J.R.R. Tolkien in a generation.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth showcases the library’s extensive collection of Tolkien’s papers, manuscripts, letters, and artwork, the largest of its kind in the world. The exhibition, which includes some 200 items, also brings together items from private collections and Marquette University’s Tolkien Collection.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973) spent most of his adult life in Oxford. He came to Oxford University in 1911, aged nineteen, to study Classics at Exeter College, but later switched to English. After serving in France during World War One, he returned to Oxford to work on the New English Dictionary (later the Oxford English Dictionary), while tutoring in English. After five years at Leeds University as Reader and then Professor of English Language, he returned to Oxford in 1925 and remained there for the rest of his working life, first as Professor of Anglo-Saxon from 1925 to 1945, and later as Professor of English Language and Literature from 1945 to 1959. He is buried with his wife, Edith, in Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford.

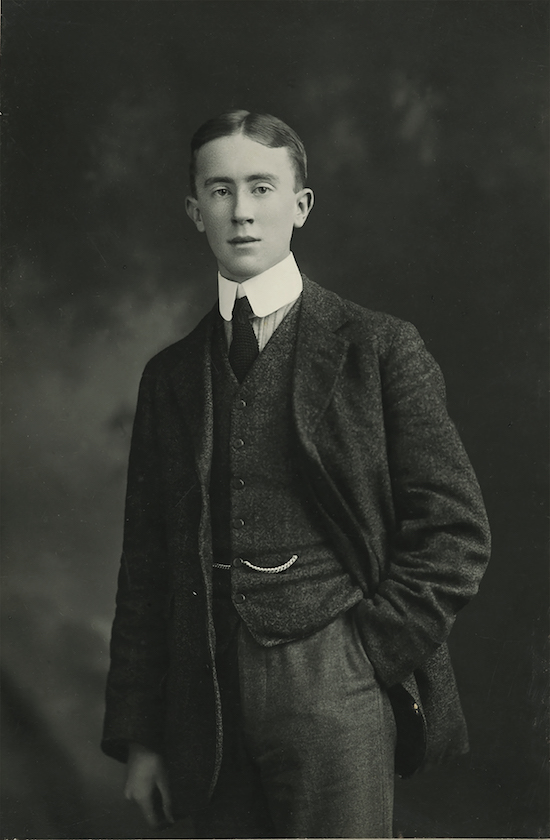

Tolkien was an able student and on his second attempt he won

an exhibition to study Classics at Exeter College, Oxford. He was

photographed in Birmingham, aged 19, shortly before leaving school

and embarking on his university career. He had enjoyed his time at

King Edward VI School, excelling in languages and in debates,

performing with gusto on the rugby pitch and in theatrical productions,

and had been at the centre of a group of close male friends.

Credit: © The Tolkien Trust 1977

The exhibition traces Tolkien’s life, including many personal effects such a letter the four-year-old future author wrote to his father, and many items related to his school days.

One amusing letter, dated 1913, talks of his joy at getting a readership at the Bodleian Library.

At 11 I put on my gown and braced myself for an ordeal I have long shelved: that is going to register myself and take the oath at the Bodleian Library as a reader. I was received better than I expected – they are very rude to some people – and then went on to the Radcliffe Camera [then the Public Reading Room to the Bodleian] to register myself there. You have no idea what an awesome and splendid place this library of wonderful manuscripts and books without price is.

As a reader at the Bodleian Library myself, I shared his joy mingled with intimidation the first time I passed through those hallowed doors. My first instinct was, “Who am I to research at one of the world’s best libraries?” Luckily the staff were polite to me too.

There is also Tolkien’s desk and chair, an assortment of his pipes, and the paint set with which he made those wonderful illustrations.

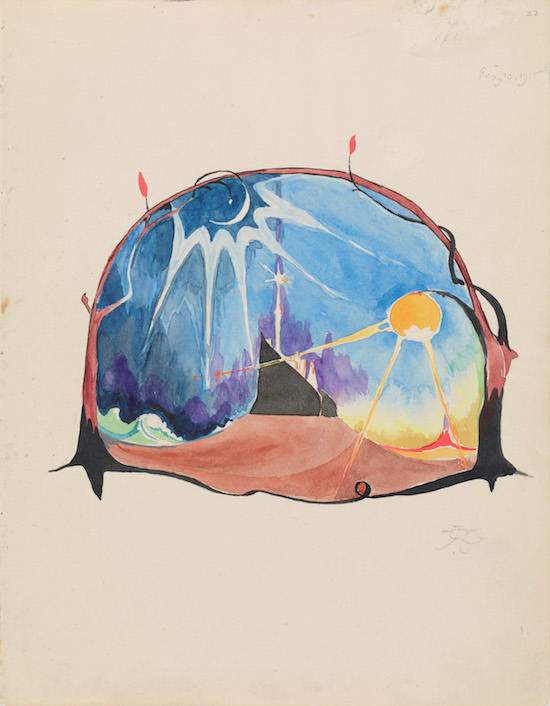

The Shores of Faery, a watercolor illustration painted by Tolkien

for The Silmarillion. This was his earliest work on the legends

of the elves, which was unfinished during his lifetime and was published

posthumously. The painting is one of the earliest known items relating to

The Silmarillion, painted when Tolkien was still an undergraduate

at Oxford. In the midst of his finals, in May 1915, he drew this depiction

of Kôr, the city of the Elves in the Blessed Land of the Gods, Valinor.

The white citadel is seen through the entwined branches of the Two Trees,

bearing the light of the moon and the sun. It is clear from this painting

that his legendarium was already well advanced. Credit: © The Tolkien Trust 1995

Those illustrations take pride of place. Some are shown here, but a photo doesn’t do them justice. The colors are rich and the detail is dazzling. I found myself staring for a long time at each one.

There are also the many detailed maps Tolkien drew. He stated that it was best to start with the map and make the narrative fit it. A meticulous writer, he even figured out how far a hobbit could walk in a day and made the storyline fit into the length of the journey. One map of Hobbiton, which he stated was on the same latitude as Oxford, has a little burn mark from his pipe. These personal touches can be found throughout the exhibition and give an intimate portrait of the great author.

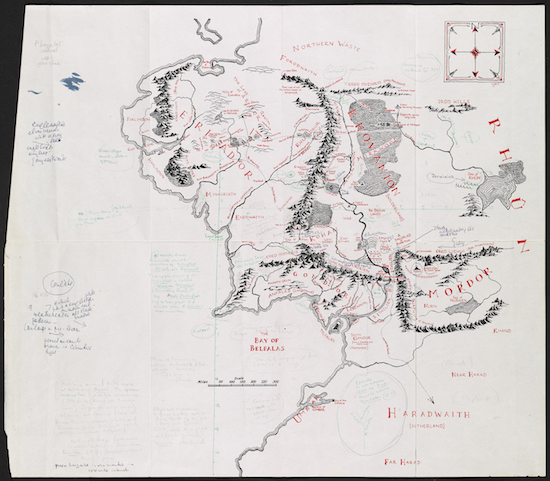

This general map of Middle-earth was included in the first two volumes

of The Lord of the Rings, an essential guide for readers navigating

through the then unfamiliar world of Middle-earth. In 1969, Tolkien

collaborated with the artist Pauline Baynes to produce a poster map of

Middle-earth. The recently discovered map was acquired by the Bodleian

Libraries in 2016. Credit: © Williams College Oxford Programme

& The Tolkien Estate Ltd, 2018

One section examines the effect his work had over time, from the first release of his works to their resurgence in popularity in the 1970s. After the publication of The Hobbit, his publishers had hoped for a Hobbit series aimed at children, got a work of adult literature instead, and accepted it on its literary merit. They did not expect it to become a bestseller. One telling photograph from this section shows a wall somewhere in the United States with graffiti demanding “Get out of Vietnam” with a swastika next to it. Tucked in the spare space, someone else wrote “Bilbo Baggins Lives.”

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth runs through October 28. It will then move to the Morgan Library in New York where it will be open from 25 January to 12 May 2019. In late 2019, it will be at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. Dates are not yet set.

Scroll down for more images!

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919.

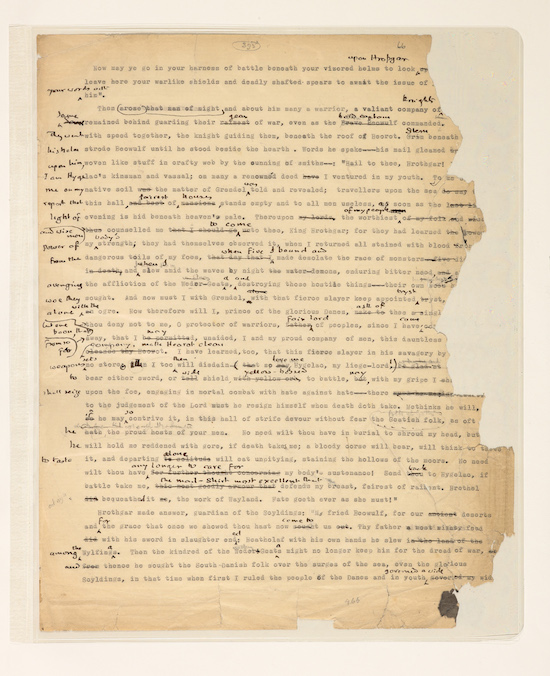

Beowulf typescript. This long alliterative poem written in Old English at

the beginning of the 11th century, was a work of huge importance to Tolkien.

He started studying Old English in 1913 as an undergraduate at Oxford, and

he continued to study, discuss, and teach Beowulf for most of his working life.

His prose translation of the poem was completed about 1926, shortly after

taking up the position of Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. This document

has never been displayed before. Credit: © The Tolkien Trust 2018

The Gardens of the Merking’s palace, an illustration Tolkien completed for

“Roverandom,” a bedtime story originally told to his children in 1925 about

the adventures of a young dog. By 1927, Tolkien’s growing family of three

sons had sent his imagination in the direction of children’s stories. A

family holiday in Filey on the North Yorkshire coast was marred by the loss

of his son Michael’s toy dog on the beach. To calm the children during a

particularly stormy night in their cliff-top lodgings, Tolkien told them

the story of a real dog Rover, who was changed into a toy dog by a passing

wizard. Rover had many adventures including a sojourn under the sea in the

Merking’s palace before being restored to his true form and to his loving

family. This watercolor shows the underwater gardens that the fictional

dog explored in the story. “Roverandom” was submitted for publication in

1937 after the success of The Hobbit, but was not published for

over sixty years, finally being released in 1998. Credit: © Tolkien Trust 1992

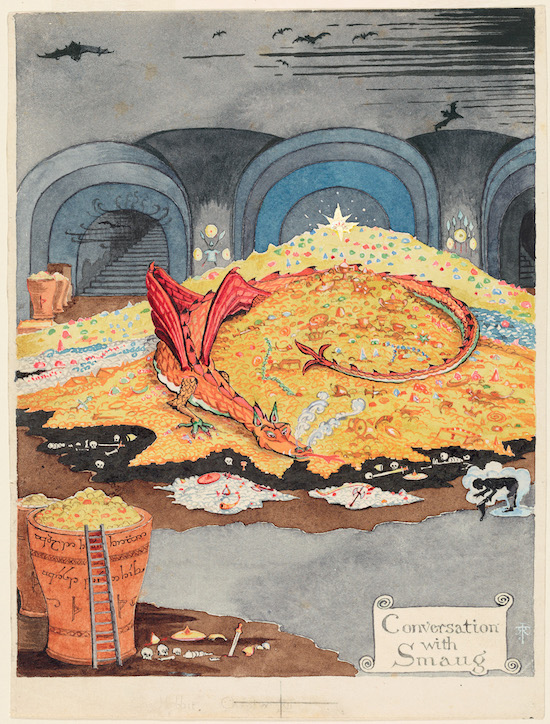

Conversation with Smaug, a watercolor painted by Tolkien

in 1937 as an illustration for the first American edition of

The Hobbit. In this image, Bilbo Baggins, rendered

invisible by a magic ring, converses with the fire-breathing

dragon, Smaug. Credit: © The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937

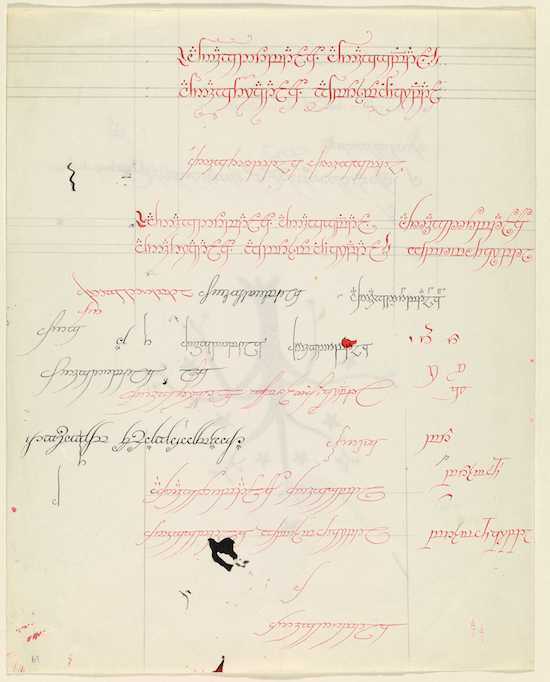

“Frodo… saw fine lines, finer than the finest pen-strokes, running along

the ring, outside and inside: lines of fire that seemed to form the letters of

a flowing script. They shone piercingly bright, and yet remote, as if out of a

great depth. ‘I cannot read the fiery letters’, said Frodo in a quavering voice.

‘No’, said Gandalf, ‘but I can. The letters are Elvish, of an ancient mode, but

the language is that of Mordor, which I will not utter here.’ [The Lord of

the Rings, Book I, ch. 2]

Tolkien experimented with many different styles of Tengwar, the

Elvish language, before electing the most appropriate one for the lines

of the ring verse. The lettering used in the book most closely resembles the

two lines in red, bottom center. Credit: © The Tolkien Trust 2015

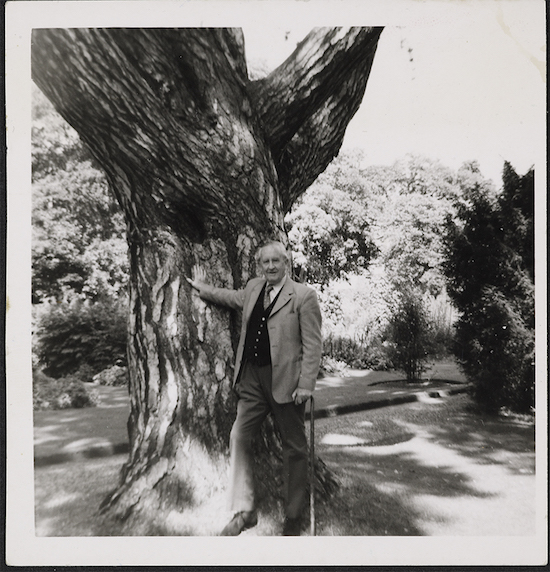

A portrait of JRR Tolkien taken on 9 Aug 1973. This was the last

photograph taken of Tolkien in the Botanic Garden, Oxford, next to

his favorite tree, the Pinus Nigra. He died less than a month later.

Credit: © The Tolkien Trust 1977

Oh, man, I really need to go back to England sooner rather than later.

When my wife was teaching in Liege, Belgium, in 1992 we got to know a lot of the grad students. At a party, one of them mentioned that one of his professors had been a grad student of J.R.R. Tolkien, and that “all his grad students were his beta readers.”

He got up, and came back a few minutes later with a manuscript. It was an early version of THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING. The poem “Nine Rings to Rule Them All…” on the front page was very different, and it had been updated by hand (in red ink) to the version I was familiar with. The student casually mentioned that all the changes in red were by Tolkien’s own hand.

It’s one of my most vivid memories from the year we spent in Belgium. I checked out the story later, and learned that at least one of Tolkien’s grad students was from Belgium.

I don’t know what happened to that manuscript. I hope it ended up in a museum somewhere!

It belongs in a museum!

I went to this and it was amazing. If you’ve read Humphrey Carpenter’s biography of Tolkien (or I’m sure many others) you’ll get to see many of the pictures he uses’ actual original versions! Plus there are so many drawings and little doodles and extras. I really really enjoyed it, even if the room is fairly small. Would like an excuse to get to Oxford again sometime soon.

[…] McLachlan on Black Gate on-line magazine gives a nice report on the extensive exhibition of the works of Prof. J. R. R. Tolkien that are […]