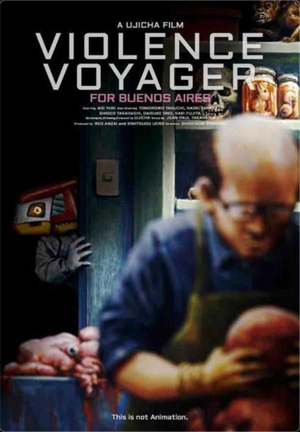

Fantasia 2018, Day 13: Violence Voyager

Late in the evening of Tuesday, July 24, I made my way to the J.A. De Sève Theatre for my one film of the day: Violence Voyager, an 83-minute animated feature by Japanese writer-director Ujicha. We follow an American schoolboy in Japan, Bobby (Aoi Yuki), as he and his friend explore some hills near his home. They find a strange, nearly-abandoned amusement park, but upon entering find themselves caught up in a terrible scheme. They and other children are captured, mutilated, mutated, and (in many cases) killed. Can Bobby free himself and others, and destroy the horrible place called Violence Voyager?

Late in the evening of Tuesday, July 24, I made my way to the J.A. De Sève Theatre for my one film of the day: Violence Voyager, an 83-minute animated feature by Japanese writer-director Ujicha. We follow an American schoolboy in Japan, Bobby (Aoi Yuki), as he and his friend explore some hills near his home. They find a strange, nearly-abandoned amusement park, but upon entering find themselves caught up in a terrible scheme. They and other children are captured, mutilated, mutated, and (in many cases) killed. Can Bobby free himself and others, and destroy the horrible place called Violence Voyager?

The first and overwhelming impression of the movie is of a dissonant strangeness. There’s a tone like a children’s story that seems destined to give way to something darker, and indeed it does, but then that darkness itself is hardly taken seriously. There’s a weird unconcern with traditional narrative effects at the same time that the structure’s remarkably tight. It’s not like much else I’ve seen, for better and worse.

Consider the animation style. It’s an unusual form called gekimation, which involves moving flat images. Lips don’t move, faces don’t shift. Shapes are moved about, and cuts give a further illusion of movement. This works better than one might think, especially once a few minutes have passed and the viewer’s assimilated the approach. Occasionally actual fluids or the like are used as visual elements as well, but mainly one watches painted pieces of paper slide over backgrounds. The art style’s intriguingly organic, with every brushstroke visible. I personally thought it was interesting without being attractive, but I can see how it could appeal more strongly to others.

As a story, there’s a sort of tension between horror and satire. It is genuinely transgressive, with all sorts of horror inflicted on children. There are genuinely surprising images here, as for example a rack of dead nude children (and the explicit nudity in some sequences is occasionally more surprising than the violence). And yet it feels muted, almost, by the thoroughgoing irony of the film. It avoids outright death-metal grotesquerie in place of its own kind of strangeness, and somehow never feels as confrontational as it seems to aim for. The early air of an optimistic children’s cartoon is never wholly abandoned, and rather than heighten the air of monstrosity, I find it functions as an alienation effect — it swathes the movie in a distancing irony, lessening the immediacy of everything we see.

Perhaps because of the constant sense of irony, I felt there was a lack of some necessary cleverness. That is: the kind of irony the film uses implies (to me) a distance justified by some sort of broader sensibility. The story and characters are under a kind of microscope, which is used to highlight some aspect that is the film’s point. I didn’t get much of a sense of that point; there was no sophistication I could see to the irony. The movie felt too obvious too often, as though it were a series of gags playing to Nelson Muntz and Corey Lewandowski — a story designed to elicit a chorus of “ha ha” and “womp womp.”

Perhaps because of the constant sense of irony, I felt there was a lack of some necessary cleverness. That is: the kind of irony the film uses implies (to me) a distance justified by some sort of broader sensibility. The story and characters are under a kind of microscope, which is used to highlight some aspect that is the film’s point. I didn’t get much of a sense of that point; there was no sophistication I could see to the irony. The movie felt too obvious too often, as though it were a series of gags playing to Nelson Muntz and Corey Lewandowski — a story designed to elicit a chorus of “ha ha” and “womp womp.”

To me the irony keeps the story from really landing. It feels less immediate than it could have been, less effective as a story. The basic structure’s fine. But the film moves slowly, or feels as though it does: as though everything’s held up to a microscope to show how unserious it is. The story has a fine horror-movie base, but in this treatment the tone never deepens. The movie’s flat. I assume this was deliberate, and certainly the limited animation works with the broad voice acting and overwrought dialogue. I think the movie succeeds at what it wants to do. I just don’t understand why it wants to do these things.

The conclusion of the story feels like a satire of a standard Hollywood action movie, and that’s fine. But nothing leading up to that conclusion seems to point in that direction. Roughly speaking, there’s a first section or act that’s a parody of a boys’-own adventure story, a long middle section of deepening horror including much body horror and a cruel transformation of the lead character, then a heroic conclusion. All of them always being sent up by the movie’s own stylistic approach. But that style only really feels in harmony with the structure in the last section, when the story becomes as self-conscious as the treatment of the material. That treatment makes it impossible, at least for me, to take the story seriously even as the story itself is well shy of the ludicrous.

The conclusion of the story feels like a satire of a standard Hollywood action movie, and that’s fine. But nothing leading up to that conclusion seems to point in that direction. Roughly speaking, there’s a first section or act that’s a parody of a boys’-own adventure story, a long middle section of deepening horror including much body horror and a cruel transformation of the lead character, then a heroic conclusion. All of them always being sent up by the movie’s own stylistic approach. But that style only really feels in harmony with the structure in the last section, when the story becomes as self-conscious as the treatment of the material. That treatment makes it impossible, at least for me, to take the story seriously even as the story itself is well shy of the ludicrous.

Perhaps just as the horror-story aspect’s implied in the boys’-own beginning, the parody of the conclusion’s meant to be implied in the horror and the beginning. If so I think it’s a misstep. Possibly the horror genre has too intricate a relationship with parody and self-parody for the irony here to work; it’s sometimes hard to know how over-the-top a horror story’s meant to be, and the reading one gives a horror story may vary dramatically with the individual.

Whether that comes into play here or not, I can’t see how to appreciate the film. In some ways I’d like to. It’s not lacking for imagination. And clearly a lot of work has been put into it. I just don’t particularly understand why. I’m not sure I know what Ujicha’s aiming at. I don’t feel this movie works as horror, and I don’t think it works as parody. There are good pieces here, and a number of moments that provoked nervous or unbelieving laughter from the Fantasia crowd (which is a good sign). But the strangeness that never wholly goes away never really is so dominant as to make the film work. The basic storyline is actually too coherent, too familiar. The parody becomes too obvious, and the film correspondingly less weird. As a whole, I don’t think it works, and I can’t see a way by which it could work. It’s an interesting experiment, but for me, a failure.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.