Fantasia 2018, Day 12, Part 2: I Am a Hero, Bleach, and Inuyashiki

I had three consecutive movies I wanted to watch on July 23. All three came from director Shinsuke Sato, all three were live-action manga adaptations, and all three were followed by question-and-answer sessions with Sato (the first at the De Sève Theatre, the second two at the larger Hall). I’ll write up what he had to say about his films in a separate post tomorrow. Today, my impressions of the movies themselves: the zombie apocalypse thriller I Am a Hero, the supernatural epic Bleach, and the science-fictional super-hero movie Inuyashiki. Note that I have read precisely none of the original works these movies were based on, and can speak only to the films I saw.

I had three consecutive movies I wanted to watch on July 23. All three came from director Shinsuke Sato, all three were live-action manga adaptations, and all three were followed by question-and-answer sessions with Sato (the first at the De Sève Theatre, the second two at the larger Hall). I’ll write up what he had to say about his films in a separate post tomorrow. Today, my impressions of the movies themselves: the zombie apocalypse thriller I Am a Hero, the supernatural epic Bleach, and the science-fictional super-hero movie Inuyashiki. Note that I have read precisely none of the original works these movies were based on, and can speak only to the films I saw.

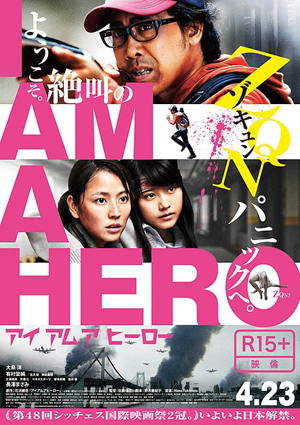

I Am a Hero (Ai Amu a Hiro, アイアムアヒーロー) was written by Akiko Nogi based on the manga by Kengo Hanazawa. Hideo (Yo Oizumi, Tokyo Ghoul) is a 35-year-old assistant to a manga creator, his aspirations and dreams dead or dying. Then the world suffers a zombie apocalypse from the spread of a deadly virus. Survivors flee to the top of Mount Fuji, because the virus can’t survive in the rarified air high up the mountain. Hideo scrambles to flee urban Tokyo, which is degenerating into mayhem; along the way he picks up a sidekick, a schoolgirl named Hiromi (Kasumi Arimura). Hiromi’s bitten by a zombie but instead of dying shows some strange powers and falls into a coma. The hapless Hideo — “the entire world changed, but I didn’t,” he groans — brings her along as he finds a community of survivors holed up in a mini-mall, and struggles to survive the tensions and suspicions he causes within the group.

The movie’s entertaining but oddly structured. The scenes early on, as Tokyo falls prey to the zombies, are fast and filled with explosions, with an epic scale that drops away for the rest of the film. Hideo’s discovery of the survivors in the mall in particular feels like a real slackening of the tension. And the climax of the film isn’t especially satisfying — it’s a big fight, but not a particularly imaginative one, and the challenges aren’t met by any new development in character or theme. It feels like more of the same rather than a rising to a satisfying end.

Moreover, on a basic plot level, more’s left unexplained and undeveloped than I’d like. Specifically, Hiromi’s powers, established early on, don’t return. She herself never wakes up from her coma. Apparently there was a scene shot for the end of the film which would have established that she held the key to a cure of the virus, but that exchange was dropped for the sake of the flow of the ending; I can understand the thinking, but that information needed to be put into the film somewhere, I think. As it is, Hiromi seems to exist mainly to show that Hideo has some spark of heroism latent within him, as he tries to save her from the madness of the world. That’s fine to a point, but effectively turns her into a plot coupon with no agency of her own.

This is essentially a movie wholly focussed on Hideo’s development into a hero, then, and one unconcerned with anything else. It’s convincing on that level, but feels insufficient. Hideo’s arc on its own isn’t enough to make the film work if only because it’s so direct and uncomplicated. He carries a shotgun around for most of the film that he never uses; we know the ending’s going to be his finally using the thing, but the battle that prompts this is as simple as the rest of his journey. Nothing’s especially surprising here.

This is essentially a movie wholly focussed on Hideo’s development into a hero, then, and one unconcerned with anything else. It’s convincing on that level, but feels insufficient. Hideo’s arc on its own isn’t enough to make the film work if only because it’s so direct and uncomplicated. He carries a shotgun around for most of the film that he never uses; we know the ending’s going to be his finally using the thing, but the battle that prompts this is as simple as the rest of his journey. Nothing’s especially surprising here.

Exacerbating this is the fact that the movie’s shameless in its use of the conventions of the zombie film. Social apocalypse, zombies in a former shrine to consumerism, a community of survivors whose internal tensions are as dangerous as the monsters beyond — all these things feel very familiar. There’s not much of a feel of any development of them, either, as the movie tends to break down into a series of episodes.

There are some very strong elements in this film. The early Tokyo scenes are spectacular, as they needed to be. The fight choreography all through is excellent. The moments of both horror and straight-faced humour land, with one flipping easily into the other. It’s highly watchable moment to moment, well-shot and well-played. As a package it’s unsatisfying, but as a series of incidents it almost works. Hideo does give the story a through-line, but the lack of plot connection between sections is notable.

I will say that the zombies are reasonably original, and do help bring out Hideo’s development. These zombies tend to repeat over and over the things they did in life. Businessmen continue to talk on their phones arranging deals even as they crave the flesh of the living. Athletes train. Shoppers shop. The dead are caught up in their routines. Hideo’s challenge, then, is specifically to change and grow. Meanwhile, the cartoonish aspect perhaps inherent to the idea of the zombie is pushed both for laughs and for the sake of creating individual opponents — the zombies, each with their own obsession, are in theory not just an undifferentiated mass. I’m not sure how much that works, because ultimately they all operate by the same rules and are vulnerable to the same kill-shots. But at least they each provide a different visual spectacle.

I will say that the zombies are reasonably original, and do help bring out Hideo’s development. These zombies tend to repeat over and over the things they did in life. Businessmen continue to talk on their phones arranging deals even as they crave the flesh of the living. Athletes train. Shoppers shop. The dead are caught up in their routines. Hideo’s challenge, then, is specifically to change and grow. Meanwhile, the cartoonish aspect perhaps inherent to the idea of the zombie is pushed both for laughs and for the sake of creating individual opponents — the zombies, each with their own obsession, are in theory not just an undifferentiated mass. I’m not sure how much that works, because ultimately they all operate by the same rules and are vulnerable to the same kill-shots. But at least they each provide a different visual spectacle.

I wonder how much Mount Fuji should be read here as symbolic. We never do see Hideo reach it; it’s a destination towards which he aspires, then, not a concrete reality. Does it represent some kind of spiritual state that wipes away the dull habits of ordinary life? Does Hideo symbolically have to evolve to become a hero before he can reach it? I don’t know, but it’s at least possible to see it in those terms, I think. The problem, again, is that the obstacles between him and this salvation don’t seem to me to be original or dramatically coherent.

I Am a Hero is a competent movie, but it feels to me as though its interest is not in its story or even necessarily in its genre elements. It’s focussed on Hideo’s growth, which is fine, but its plot construction is too ramshackle — proceeding in fits and starts, developing through separate episodes instead of logically unfolding from one thing to another, dropping too many subplots. Other characters feel rudimentary or flat. Hideo’s emergence as a hero is ultimately undercut, I think, by the lack of personalities around him. Neither the heroic nurse (Masami Nagasawa, Gintama) he finds among the survivors nor their shifty leader (Yoshinori Okada) feel especially developed. It’s a well-crafted film in some ways, but in the end unsatisfying. (Though I must say this: while I haven’t read the manga, if the plot descriptions in Wikipedia are at all accurate, it would appear that some tasteful decisions have been made in adapting it, particularly in terms of Nagasawa’s character and of the relationship between Hideo and Hiromi.)

I Am a Hero is a competent movie, but it feels to me as though its interest is not in its story or even necessarily in its genre elements. It’s focussed on Hideo’s growth, which is fine, but its plot construction is too ramshackle — proceeding in fits and starts, developing through separate episodes instead of logically unfolding from one thing to another, dropping too many subplots. Other characters feel rudimentary or flat. Hideo’s emergence as a hero is ultimately undercut, I think, by the lack of personalities around him. Neither the heroic nurse (Masami Nagasawa, Gintama) he finds among the survivors nor their shifty leader (Yoshinori Okada) feel especially developed. It’s a well-crafted film in some ways, but in the end unsatisfying. (Though I must say this: while I haven’t read the manga, if the plot descriptions in Wikipedia are at all accurate, it would appear that some tasteful decisions have been made in adapting it, particularly in terms of Nagasawa’s character and of the relationship between Hideo and Hiromi.)

Bleach was written by Daisuke Habara, based on the long-running manga by Tite Kubo. Teenager Ichigo Kurosaki (Sota Fukushi, Blade of the Immortal, Laplace’s Witch, Satoru in The Travelling Cat Chronicles) has the ability to see ghosts. When he stumbles into a conflict between a death god, a shinigami or Soul Reaper, and a monstrous spirit called a Hollow, he ends up being given the Reaper’s power and destroying the Hollow. The Reaper, Rukia (Hana Sugisaki, also of Blade of the Immortal), decides to train him as she recovers from her injuries. But not only is a powerful Hollow called the Grand Fisher lurking about, Rukia’s family is coming to reclaim her — and destroy the human in whom she’s vested her powers.

Bleach was written by Daisuke Habara, based on the long-running manga by Tite Kubo. Teenager Ichigo Kurosaki (Sota Fukushi, Blade of the Immortal, Laplace’s Witch, Satoru in The Travelling Cat Chronicles) has the ability to see ghosts. When he stumbles into a conflict between a death god, a shinigami or Soul Reaper, and a monstrous spirit called a Hollow, he ends up being given the Reaper’s power and destroying the Hollow. The Reaper, Rukia (Hana Sugisaki, also of Blade of the Immortal), decides to train him as she recovers from her injuries. But not only is a powerful Hollow called the Grand Fisher lurking about, Rukia’s family is coming to reclaim her — and destroy the human in whom she’s vested her powers.

There’s a real big-budget feel to this movie; a lot of CGI, mostly used well, and an extended climax that goes through a series of fights. Fukushi’s Ichigo manages to stand out, though, and keeps the movie from feeling like a bunch of video-game cut-scenes. That’s important because the movie adds new ideas and new concepts at breakneck speed. The ending even feels as though it leaves a few things unexplored, specifically a supernatural otherworld of which we get merely a few glimpses.

If this is a plot-centred film, the plot’s well-built. It sets up its climax in its first act, and pays off everything it builds up along the way. It uses a variety of strands to establish character and set up challenges. And it’s always clear and consistent in depicting the relative power levels and relative danger of the various entities in the film. These things are managed at a high velocity, with a lot of humour flavouring the story. It’s an entertainment above all, and a successful one.

Some bits of the plot are moved over very quickly. Ichigo’s classmate Uryu (Ryo Yoshizawa, Gintama), who turns out to come from a people destroyed by the Soul Reapers, effectively exists to provide a different angle on the Reapers; his own story isn’t explored. An outcast Reaper running a magic shop (Seiichi Tanabe) is perhaps a little underplayed. But then another way to look at it is to say that they contribute just what they need to, in terms of Ichigo’s story and in terms of developing his world. At the least, nothing here feels like merely a plot contrivance.

Ichigo himself is an engaging hero, angry because of the death of his mother (I Am A Hero’s Masami Nagasawa) when he was a child, but not broken or bitter. His interaction with Rukia is lively enough to make a credible core of the film. His interactions with his family and especially his classmates are much less developed, but they’re not really why we’re here (and those characters are developed enough to get moments of their own before the film ends). The point is that we get a sense of Ichigo’s everyday life which proceeds to get upended. This isn’t really a movie about Ichigo struggling to fit into the everyday world, it’s a film about him struggling to negotiate the more dangerous world into which he has been drawn.

Ichigo himself is an engaging hero, angry because of the death of his mother (I Am A Hero’s Masami Nagasawa) when he was a child, but not broken or bitter. His interaction with Rukia is lively enough to make a credible core of the film. His interactions with his family and especially his classmates are much less developed, but they’re not really why we’re here (and those characters are developed enough to get moments of their own before the film ends). The point is that we get a sense of Ichigo’s everyday life which proceeds to get upended. This isn’t really a movie about Ichigo struggling to fit into the everyday world, it’s a film about him struggling to negotiate the more dangerous world into which he has been drawn.

That world itself is a pleasure to watch. The creature designs are solid, and the costume designs effective. There’s no sense here of designs toned down to compromise with reality. There are big splashy costumes in the modern world, and if they jar with an everyday setting, the everyday world will just have to make room. This is essentially an urban fantasy, with a secret supernatural realm impinging on contemporary urban life, and it works. The sense of a hidden truth of the world with more meaning and danger comes across, and is rightfully the focus.

A lot of solid genre ideas are given new spins. The teacher training a resentful pupil works well, as Rukia trains Ichigo in the use of his almost comedically large sword by pelting him with tennis balls from an automatic launcher. Ichigo’s fights have all the quick movement and dramatic reverses you could want, with one challenge giving way to a bigger one. This is a movie that knows what it wants to do, seems to be having fun, and gives the audience what they want.

A lot of solid genre ideas are given new spins. The teacher training a resentful pupil works well, as Rukia trains Ichigo in the use of his almost comedically large sword by pelting him with tennis balls from an automatic launcher. Ichigo’s fights have all the quick movement and dramatic reverses you could want, with one challenge giving way to a bigger one. This is a movie that knows what it wants to do, seems to be having fun, and gives the audience what they want.

It’s a story of heroes and villains, with the hero reluctant in some ways but acting in the end to protect those he cares about, and villains who feel linked to him on a personal and thematic level. Like a lot of big action movies, it has the sense of a family drama writ large — the Grand Fisher turns out (and I don’t think this is a surprise) to be linked to Ichigo’s past, and by the end he must defeat it to save his family and friends. Meanwhile, if Ichigo’s shaped by his family, Rukia’s family provides another level of threat; there’s a useful contrast to be drawn there. It’s not something especially subtle or especially deep, but enough to give the movie the feel of a symbolic subtext.

This isn’t, as I say, a profound film. But it’s a very good imaginative action movie. The acting’s broad but not too much so; like a Marvel movie, it memorably establishes larger-than-life characters. Fukshi’s charisma lets him stand out among all the chaos, and the quick pacing means the story never flags. It shouldn’t; the manga ran for 15 years over 74 volumes. There’s a lot there to draw from (though I gather this movie, also known as Bleach: The Soul Reaper Agent Arc, is based primarily on one storyline). It comes together nicely, and the result is an energetic and entertaining film.

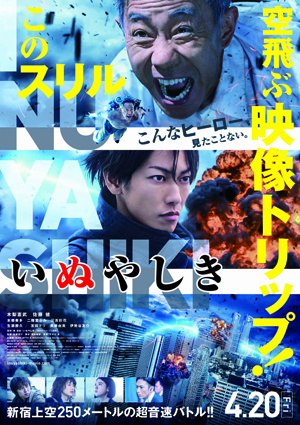

Inuyashiki, scripted by Hiroshi Hashimoto from the manga by Hiroya Oku, is a super-hero story. An old man, Ichiro Inuyashiki (Noritake Kinashi), and a young man, Hiro Shishigami (Takeru Satoh, star of the Rurouni Kenshin movies and If Cats Disappeared from the World), are in a park at the same time when a mysterious object crashes to Earth. Both men are transformed, rebuilt as cyborgs with strange and wondrous powers. Hiro soon begins to abuse his new might. Ichiro, mocked by his family, held in contempt by his coworkers, is delighted to find that he can heal the sick. A confrontation between the two of them feels inevitable, and is; and the spectacle of their fight makes for a memorable climax.

Inuyashiki, scripted by Hiroshi Hashimoto from the manga by Hiroya Oku, is a super-hero story. An old man, Ichiro Inuyashiki (Noritake Kinashi), and a young man, Hiro Shishigami (Takeru Satoh, star of the Rurouni Kenshin movies and If Cats Disappeared from the World), are in a park at the same time when a mysterious object crashes to Earth. Both men are transformed, rebuilt as cyborgs with strange and wondrous powers. Hiro soon begins to abuse his new might. Ichiro, mocked by his family, held in contempt by his coworkers, is delighted to find that he can heal the sick. A confrontation between the two of them feels inevitable, and is; and the spectacle of their fight makes for a memorable climax.

Perhaps the most striking part of this movie is simply the sense of inevitability to it. The build of the story is incredibly effective. The two characters are fleshed out swiftly, shown to be opposites, exploit their powers in different ways, and move along toward their ultimate conflict. We can see the shape of the story, then, but it’s not predictable. The characters are vivid enough that they do surprise us, not just the leads but also Hiro’s best friend Naoyuki (Kanata Hongo, Attack on Titan). And the movie very effectively develops from a small, quiet scale early on to big-screen devastation reminiscent of Man of Steel at the end — without the sense of a moral vacuum that movie created.

As a super-hero story, it’s very good. The powers the two men get, and the different abilities they choose to develop, bring out their personalities. The genre-conscious Hiro tells Naoyuki he’s a super-hero, and demonstrates by crashing two cars into each other — heedless property damage that indicates a basic lack of concern with the world around him. Ichiro’s uninterested in becoming a hero, uninterested in finding out all that he can do. He’s just happy to find he can help others, anonymously healing people. It never occurs to him to use his powers for combat. That’s not who he is.

In fact, part of the theme of the movie comes from the way in which the alliteratively-named Ichiro Inuyashiki joins the pantheon of secret-identity doormats. Like Clark Kent and Peter Parker, the people around him consider him a hapless weakling. This sometimes comes across rather broadly, especially in his interactions with his family, and the marked disrespect and disobedience his children show him. But there’s a point to it, I think. Hiro’s of an age with the Inuyashiki kids; if the traditional super-hero story from America tends to involve a younger hero fighting an older — consider Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus or the Green Goblin, Superman and Lex Luthor, Fawcett’s Captain Marvel and Doctor Sivana, or perhaps the purest expression of the super-hero, Jack Kirby’s Orion and Darkseid — then here we have a story of an older man struggling against youth. Instead of a young man’s idealism against aged corruption, here an older man’s equanimity is pitted against a young man’s indiscipline and wildness.

The movie gives us a number of images of young people running wild — Hiro and Naoyuki’s teacher, for example, has no control whatsoever of her classroom. Ichiro’s disrespected by his younger boss as well as his officemates. Notably, though, this doesn’t feel like a conservative story of old folks putting some kind of hierarchy in place over the young. It’s more like a fable of a generation that failed its responsibility to provide guidance coming to terms with its failure while still struggling to allow for the possibility of a meaningful future. It’s strongly in the tradition of the super-hero story presenting a symbolic generational drama, then, but finds a new spin on old material.

The movie gives us a number of images of young people running wild — Hiro and Naoyuki’s teacher, for example, has no control whatsoever of her classroom. Ichiro’s disrespected by his younger boss as well as his officemates. Notably, though, this doesn’t feel like a conservative story of old folks putting some kind of hierarchy in place over the young. It’s more like a fable of a generation that failed its responsibility to provide guidance coming to terms with its failure while still struggling to allow for the possibility of a meaningful future. It’s strongly in the tradition of the super-hero story presenting a symbolic generational drama, then, but finds a new spin on old material.

It helps that the lead actors are both very strong. Ichiro’s near-terminal mild-manneredness is just the right side of parody, and Satoh’s Hiro is alternately troubled and magnificently amoral. There’s a very human heroism to Ichiro, in other words, and a villainy in Hiro that perfectly fits his role. The story adroitly has them encounter each other before the climax, roughly at a point where Hiro makes a turn into irredeemable evil; it helps show the contrast of what they already are, and becomes a point from which to get a perspective on how much further they end up going.

I mentioned Man of Steel above in speaking about that ending; the film also vaguely resembles Chronicle, but again I feel it’s much superior, specifically in terms of its character work. The final fight also seems to have nods to a number of specific films (I thought of the first Iron Man at one point) but, if it’s aware of its predecessors, wears that knowledge lightly. The fight is an extended struggle that goes back and forth and keeps going when you don’t expect it to. There’s a very real risk with the power levels of both participants that a feeling of invulnerability could arise, but it never really does; Ichiro always feels as though he’s in danger, Hiro always seems beatable (‘Surely this will finish him off,’ one thinks, but again and again, there’s more).

I don’t think this is a perfect movie. There’s an improbably stealthy SAT group, for example, and a sub-plot with a girl (Fumi Nikaido) who has a crush on Hiro that feels a trifle excessive. I don’t know whether sometimes it plays things a little bit too broadly for comfort. And certainly it can’t be accused of being excessively subtle.

I don’t think this is a perfect movie. There’s an improbably stealthy SAT group, for example, and a sub-plot with a girl (Fumi Nikaido) who has a crush on Hiro that feels a trifle excessive. I don’t know whether sometimes it plays things a little bit too broadly for comfort. And certainly it can’t be accused of being excessively subtle.

But then, this is a super-hero movie. And a good one, I think. It sets up two well-acted sides of a symbolic struggle, and builds to a massive final fight. Super-powers advance character and theme. Visual effects are imaginative and used well. It’s a movie that gets all the important things right, and does just what it wants to do.

At the end of the day, then, having seen all three movies (as well as having seen Sato’s earlier Library Wars in previous years), what had I seen?

Technically I’d say there’s a strong use of lighting and composition to get at the emotion in a scene. The classroom scenes of Bleach and Inuyashiki, for example, take place in architecturally similar spaces but feel much different. This ability to use architecture in different ways seems to me to echo the use of built-up environments as settings for important action scenes, themselves each satisfyingly significant in the overall plot structures of their respective films.

There are a lot of well-shot battles in urban Japan in these movies; cityscapes used well and creatively as the setting for acts of extreme violence and devastation. And with those battles comes a sense of consequence to all the fighting. Characters in Sato’s movies are changed by their fighting, and sometimes must change in order to fight. There’s a concern with what it means to be a hero, and how one rises to that challenge. Crucially, all these characters fight for a reason; they fight to protect someone or, in the case of Library Wars, a specific ideal.

I think Sato’s created some fine character-centred splashy genre stories. I think the theme of the development of a hero is central to his characters. I note that the leads in each of the three films I saw today were men of different ages — young Ichigo, middle-aged Hideo, old Ichiro Inuyashiki (while Iku Kasahara of Library Wars is a young woman). In other words, the same idea is shown in a variety of ways. Certainly each of the movies felt different. Not all of them were as successful as the others. But all of them had a basic sense of what they were about and what they wanted to do with character. That, much more than Sato’s adeptness with action, makes all of them at least worth a look.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.