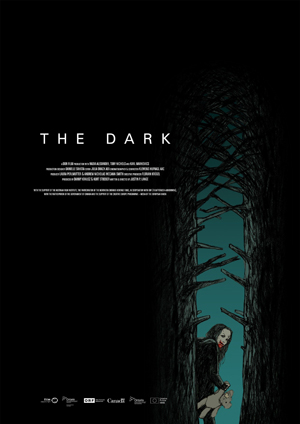

Fantasia 2018, Day 12, Part 1: The Dark

I had four movies on my schedule for Monday, July 23. Three of them were the work of one director. But before I got to those, I had an intriguing horror film at the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch first: The Dark.

I had four movies on my schedule for Monday, July 23. Three of them were the work of one director. But before I got to those, I had an intriguing horror film at the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch first: The Dark.

That screening was preceded by a short written and directed by Benjamin Swicker, “A/S/L.” I didn’t know what the title meant (an internet abbreviation for ‘age/sex/location’) and briefly thought I was about to see a film about American sign language; I was not. A middle-aged man chats up a young teenager on the internet, gets her to invite him over, and then finds out that all is not what he had thought it was. It’s competent enough, and brief, but I don’t think it gives too much away to say this is basically a vehicle for some admittedly spectacular gore effects. As such, it does the job.

The Dark was written and directed by Justin P. Lange. It’s the story of Mina (Nadia Alexander), a damaged and possibly undead girl who subsists in the woods, known by others only as a monster who kills any who enter her territory. Then one day fate brings to her an abused, blinded boy, Alex (Toby Nichols), who she doesn’t kill at once. In fact the two wounded children develop a strange bond. There’s a search afoot for Alex, though, and both police and volunteer seekers are coming into her woods. The two children go deeper into the wild, looking for some refuge together.

This is an atmospheric but highly graphic film that lets the images carry the story for long stretches. It doesn’t avoid having the characters speak to each other, but seems to invest each line with meaning. For example, it seems weirdly resonant that the first line of the movie is “You have to pay for that.” There are a lot of dark deeds done in this movie and a lot of those things come back to haunt the doer — and sometimes the sufferer. This is a movie about the cycle of abuse and characters trying, however instinctively, to move past it. But the world doesn’t make it easy, and the choices the characters make aren’t always ideal. You can literally see the damage the characters have suffered on their faces in the form of disturbing make-up effects. Whether that damage will destroy them is essentially the theme of the film.

In order to work, the movie needs great acting from two very young performers. Fortunately, it gets that. Both Alexander and Nichols do wonderful jobs under significant amounts of make-up — make-up necessary to the characters, make-up that tells a story itself over the course of the film, but make-up that covers a fair amount of their faces. The two actors overcome that with apparent ease, finding chemistry with each other and appearing to embrace the various subtexts of their characters’ histories with an almost unnerving zeal.

This is a horror movie, though, and if we’re unnerved by what we’re seeing that’s all to the good. This should not be an easy movie to watch, if it is to succeed. There’s gore in it, certainly, but not as the primary focus or as any kind of ironic entertainment. It’s brutal and meant to be, but the movie as a whole is also subtle, using the more explicit violence to set up character beats. There’s a complexity of tone here; because we see how grotesque it can be, we know that anything can happen, and that Mina in particular is capable of almost anything,

This is a horror movie, though, and if we’re unnerved by what we’re seeing that’s all to the good. This should not be an easy movie to watch, if it is to succeed. There’s gore in it, certainly, but not as the primary focus or as any kind of ironic entertainment. It’s brutal and meant to be, but the movie as a whole is also subtle, using the more explicit violence to set up character beats. There’s a complexity of tone here; because we see how grotesque it can be, we know that anything can happen, and that Mina in particular is capable of almost anything,

At the same time, there are moments that, if not uplifting, at least hint at the possibility of happiness. There’s a breathtaking image in the second half of the two children at a dining-room table, with a window beyond the table dominating the frame and hinting at some kind of pastoral arcadia. In a movie otherwise dominated by the shadows of a fairy-tale forest it stands out, a lyrical moment that contributes to the story. It’s a necessary break in the titular darkness, which otherwise dominates — particularly in the series of flashbacks that give us Mina’s backstory as a parallel plot through the film. The movie plays with shadows, nighttime scenes, and grey-toned days. It’s what you might expect from a movie called The Dark, but it’s done well, not just building a specific tone but allowing a range of tones. The shadows don’t obscure the story but contribute to it.

I will say that the movie does strain at times to include other characters and even moments of comedy. A scene with a group of volunteer hunters almost breaks the feel of the film. The way that police are used here, and specifically the number of them we see, feels convenient for the overall plot construction. These things aren’t fatal to the film, but the movie’s got a delicate logic that I felt was a bit strained in these places.

I will say that the movie does strain at times to include other characters and even moments of comedy. A scene with a group of volunteer hunters almost breaks the feel of the film. The way that police are used here, and specifically the number of them we see, feels convenient for the overall plot construction. These things aren’t fatal to the film, but the movie’s got a delicate logic that I felt was a bit strained in these places.

Perhaps it’s fairer to say that this is a movie about Mina and Alex together. It’s primarily Mina’s story; we get her background but not Alex’s, and in the end the conclusion’s structured around her choices and her capacity for growth. But the movie’s about the way the two damaged kids help each other. If there’s a weakness, then, it’s in how it interjects other plot elements to drive their interactions a certain way. I don’t think it’s a fatal weakness, but I think that the movie actually slackens in tension when outside threats are introduced.

Still, it’s a strong film that explores dark emotional terrain in a convincing way. The ending in particular is quite powerful, relatively upbeat without denying the horror we’ve just seen. Mina in particular does terrible things in this movie, and while we see how much wrong was done to her, we should, I think, be appalled at what she does. Does she end up paying for it? This isn’t that kind of movie, that provides a neat poetic justice wrapped up in a bow. I think it’s a movie that tells us that some people have to heal before they can pay for their actions.

A lot of horror movies establish the danger posed by a monster and then become about the destruction of the monster. The Dark is about a monster and about a more difficult path. It’s a more difficult movie as a result. The children here talk elliptically about things children should not have to go through, and show us the damage these things do emotionally. What I think the story argues is that these scars don’t have to end up defining who they are. It’s convincing thematically even if it has some odd narrative moments. Cinematically, the movie’s more than powerful enough to make up for these things. I think it’s a movie that has a basically simple concept that touches on the archetypal, and I think it’s symbolically resonant enough that a range of meanings can be extracted from it. The characters are rich and haunting; Mina’s aware of who she is, but not necessarily aware of her capability to grow to become something else. Much of the film is an interrogation of exactly that, and is subtle enough in doing so that its conclusion (with a long take mirroring its opening but utterly reversed in meaning) lands with real power.

A lot of horror movies establish the danger posed by a monster and then become about the destruction of the monster. The Dark is about a monster and about a more difficult path. It’s a more difficult movie as a result. The children here talk elliptically about things children should not have to go through, and show us the damage these things do emotionally. What I think the story argues is that these scars don’t have to end up defining who they are. It’s convincing thematically even if it has some odd narrative moments. Cinematically, the movie’s more than powerful enough to make up for these things. I think it’s a movie that has a basically simple concept that touches on the archetypal, and I think it’s symbolically resonant enough that a range of meanings can be extracted from it. The characters are rich and haunting; Mina’s aware of who she is, but not necessarily aware of her capability to grow to become something else. Much of the film is an interrogation of exactly that, and is subtle enough in doing so that its conclusion (with a long take mirroring its opening but utterly reversed in meaning) lands with real power.

After the film writer-director Justin P. Lange took questions. The first was about the fairy-tale aspect of the film, and whether he was influenced by the Grimms. He said there was no conscious influence, that he wrote it first and then realised that it fit that particular spectrum. He didn’t think there was a direct influence in the current film, although there was a thematic and tonal influence. He said instead that movies gave him the way into the story, citing Let the Right One In, The Devil’s Backbone, and Pan’s Labyrinth. These were films, he said, that made him think ‘maybe I do have a place in this world.’

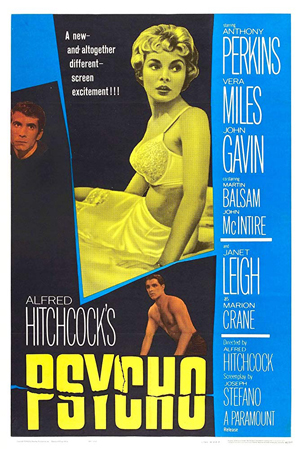

Asked if there was a Psycho influence in the opening of the film, he said “I ripped that off totally.” He said one of his favourite things about Hitchcock was structure, and whenever a film does something different with structure he’s intrigued. He said the challenge of this film was to make it from the monster’s perspective; the opening is a long character intro, after which we’re then with her. Asked about how Mina’s injuries seemed to have faded at the end of the film, he said it’s subtle but is in fact a continuum throughout the movie, most apparent in the final shot. He said the film was a metaphor for abuse and cycles of abuse, and that her ability to connect with others starts to heal her and make her more vulnerable.

Asked if there was a Psycho influence in the opening of the film, he said “I ripped that off totally.” He said one of his favourite things about Hitchcock was structure, and whenever a film does something different with structure he’s intrigued. He said the challenge of this film was to make it from the monster’s perspective; the opening is a long character intro, after which we’re then with her. Asked about how Mina’s injuries seemed to have faded at the end of the film, he said it’s subtle but is in fact a continuum throughout the movie, most apparent in the final shot. He said the film was a metaphor for abuse and cycles of abuse, and that her ability to connect with others starts to heal her and make her more vulnerable.

Asked about the long, composed shots of the movie, Lange (a Canadian) said it was function of working with Austrians, such as cinematographer Klemens Hufnagl (who is credited as co-director in some sources; the movie’s officially a Canadian-Austrian co-production). Hufnagl has a penchant for working in long takes. Lange talked a little more about the opening of the film, noting that the character there never had “access” to the camera, that the camera stays distant with no point-of-view shots; it’s not something one consciously notices, he said, but something one feels.

Asked about the makeup, he said he worked with the company behind the effects on True Blood, who had just opened an office in Toronto. Lange said everything was a balancing act; you were going to be looking at Mina for an hour and a half. You had to feel empathy, but also couldn’t skimp and just have a little scar — you had to feel what had been done to her. With Alex it was more pragmatic, using reference pictures to create a credible effect. Lange said they weren’t going for ‘shock and awe,’ just trying to be true to his experiences. The actor was 14, and Lange thought having him walking around blind on set wasn’t great; he insisted on it nevertheless. He was a brave kid, Lange said, and he’d had the prosthetics designed in pieces so he could maximise his comfort, all for naught. The make-up artists had a huge job, he said, working with the actors day-in and day-out, keeping their spirits up.

Asked about the irony of having the film be about a monster in the woods but having real monsters come from outside the woods, Lange said he rewrote the opening any number of times to get the set-up across without being too cheesy; he wanted to get across the idea that Alex’s captor went to the woods specifically because nobody else went there. He’s not sure that comes across, but he had a mentor who told him “if you’re going to make a mistake, make it in the first ten minutes of a movie; people will forget it and let it go.”

A questioner asked if it was difficult for Toby Nichols (Alex) to act, as so much acting is done with the eyes and his were obscured. Lange said he made it a lot easier because of how intelligent and mature he was. Lange wanted to tread easily with him in terms of what was happening in the backstory, but he got it anyway and worked it into his conception of the character. Lange was nervous before every scene about his line delivery, then the scene would begin and he’d knock it out of the park every time. He remembered one time the two young leads decided to rehearse a scene as though they were in a soap opera, giving really big readings. “They liked to mess with me,” he said. Nichols, he said, knew it was part of his job to make sure his feelings were in a shot, to know what’s left to him as an actor with the loss of his eyes, and to make sure he’s conveying something.

That ended the questions. I still had three more movies to go on the day.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.