Sadistic Vengeance and Grotesque Death — Still Only 20 Cents!

Just about anything goes in comics today; in terms of sex, violence, subject matter, and language, there aren’t many restraints remaining. That’s not a curmudgeonly complaint but rather a simple statement of fact, and whether the medium has become a free fire zone because of the general disappearance of boundaries in all areas of our culture, or simply because comic creators know that the overwhelming majority of their readers are adults doesn’t much matter. Whatever the cause, it’s easy to pinpoint when comics began to change (for better and worse) from what they were to what they are; the epicenter of that tectonic shift was the so-called Bronze Age, from 1970 to 1985, a period that began with a still-benign Batman polishing his giant penny and ended with Green Arrow’s kid sidekick, Speedy, shooting smack.

So many comic book barriers have come down since those far off days that it’s hard to remember when there were such barriers, and just as hard to remember the earthquake-like impact that resulted when one of those Comics Code Authority-enforced walls was breached. (One unintended but inevitable consequence of the eradication of limits is the loss of the ability to be shocked, or even to recall what being shocked felt like.)

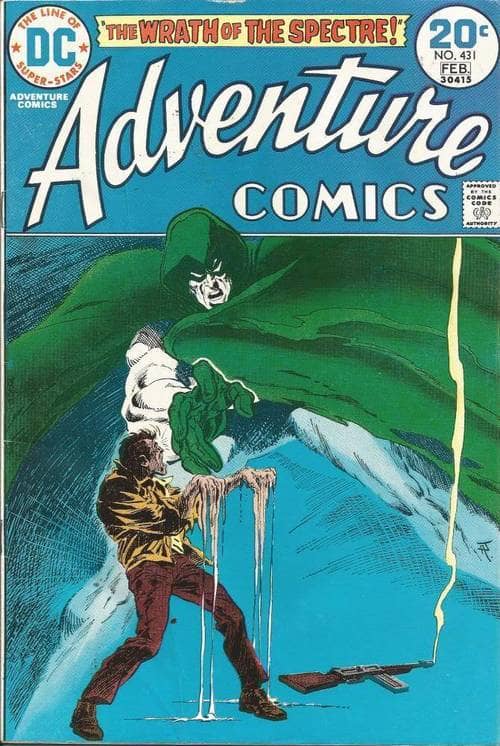

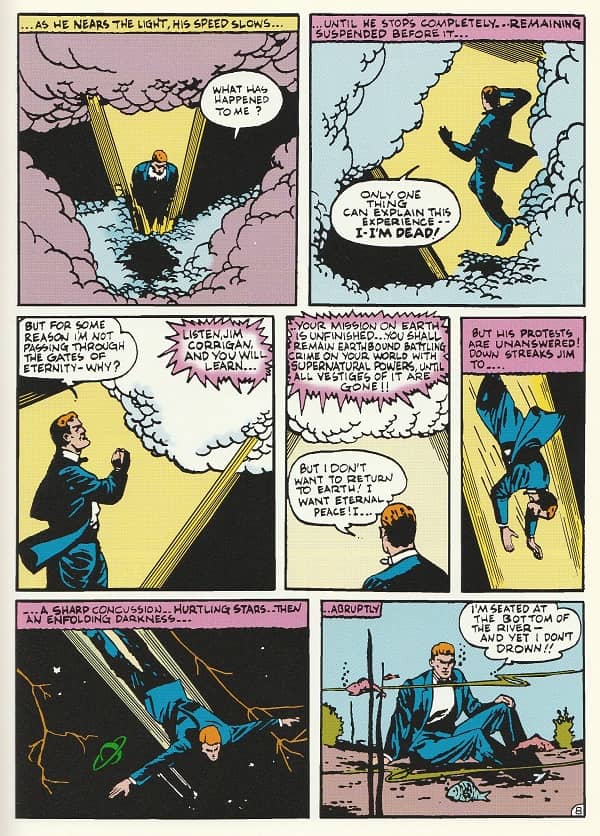

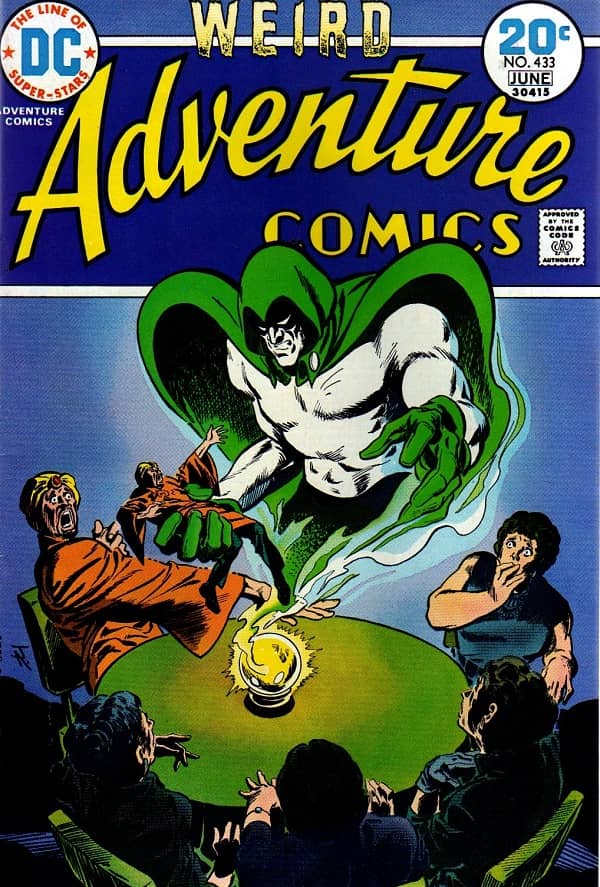

One of the key temblors of that revolutionary Bronze Age era was DC’s Adventure Comics 431, January-February 1974. It featured a character we had learned not to expect too much from — the Spectre, who had last presided over his own title for ten issues from 1967 to 1969. The twelve cent Silver Age Spectre was a comic book of unsurpassed dullness, but those of us privileged to pluck Adventure 431 off the drug store spinner rack knew very quickly that this time our two dimes had bought us something really different.

[Click the images for Spectre-sized versions.]

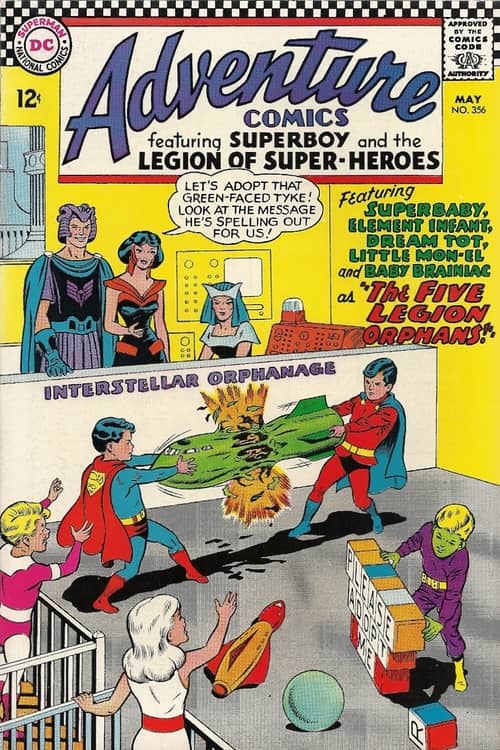

The shock was all the greater considering the source. The DC of that era was far more stolid and conventional than Marvel, and no DC product was less likely to surprise or shake up anyone than Adventure. For most of the sixties, the title belonged to the polite and clean cut Legion of Super Heroes, from whom parents had nothing to fear (they actually met in a clubhouse, for goodness sake), and when the Legion’s run ended in 1969 the book was taken over by Supergirl, a character who could always be trusted to color between the lines. (DC’s idea of throwing caution to the winds was to trade in her blue skirt for red hotpants. Oooo-la-la.)

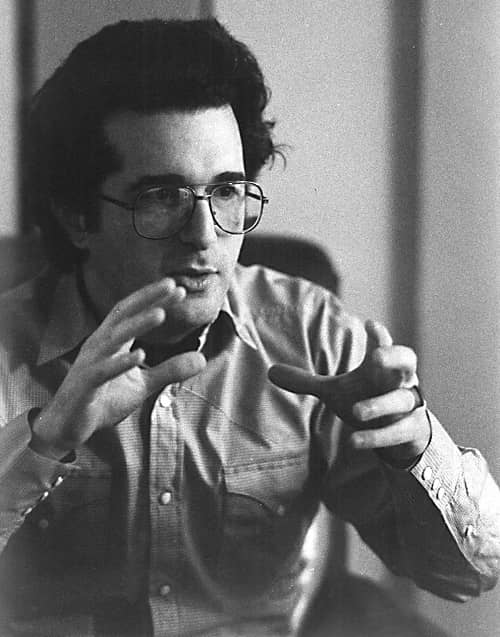

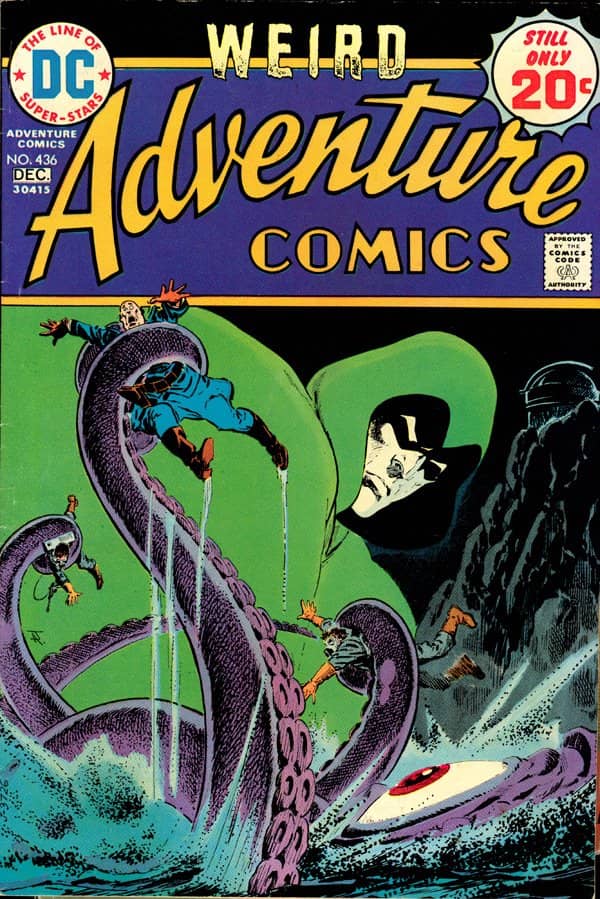

That all changed with number 431, which began a legendary and controversial ten issue Spectre series written by Michael Fleisher and drawn by Jim Aparo. Until they got their hands on him, no one ever seemed to know what to do with the character, but Fleisher and Aparo would decisively redefine the Spectre, scrubbing him clean of his accrued Silver Age blandness and taking him all the way back to his grim Golden Age roots — and then some.

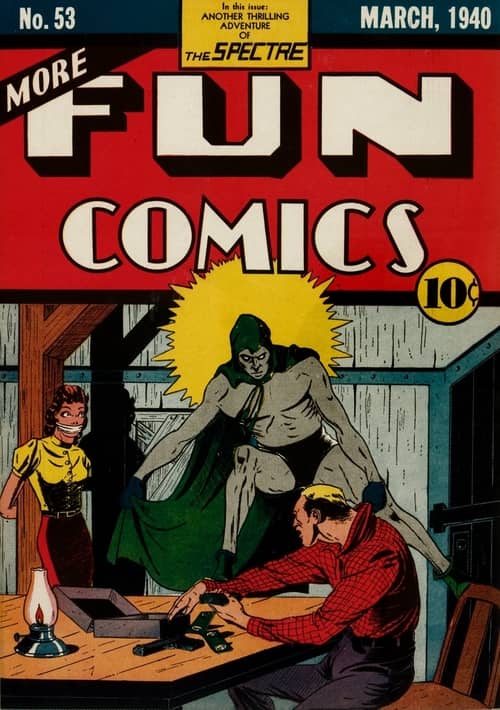

The Spectre first appeared in 1940, the creation of writer Jerry Siegel and artist Bernard Baily. (A couple of years before, Siegel had enjoyed some moderate success with a “long underwear” hero that you may have heard of — Superman.) The Spectre’s shtick was perfectly summed up in his second appearance (in More Fun Comics 53, March 1940), in one of those synopsis paragraphs comics used to provide so that kids could jump right into the story: “When Jim Corrigan, detective, was slain by ‘Gat’ Benson’s gangsters, he learned that his spirit was to remain earthbound, battling crime with supernatural powers until it was wiped off the face of the earth.”

No rest until all crime is eradicated everywhere? That’s what you call job security, but it also explains why the Spectre tends to take things personally. All Jim Corrigan wants is some well earned rest, but every time some creep steps outside the law, his eternal vacation gets indefinitely postponed. It would put anyone in a bad mood.

For most of his career, the Spectre’s powers were virtually unlimited and given his barely controlled fury and lack of restraint he was rarely content to merely send people to jail. Thus in one early story he strips the flesh off one malefactor, leaving the unfortunate lawbreaker a literal living skeleton (“You’ve robbed — you’ve killed — and this is your reward!” he sternly explains) and in another he swells up to enormous size — one of his favorite tricks — and snares a sedan full of fleeing thugs. Contemptuously dismissing their frantic pleas for mercy, he crushes the car and its hapless occupants like an overripe kiwi.

It’s not quite as bad as it sounds, though, because in his earliest Golden Age appearances, the impact of the Spectre’s nasty methods was largely blunted by the crudeness of that era’s art and writing. Even with that, he soon switched to fighting evil sorcerers, malevolent entities from odd-numbered dimensions, and other such-like astral menaces; they seemed a better match for his infinite power than the Warner Brothers-style hoods he started out battling.

Then, with the advent of the Comics Code and its restrictions on supernatural characters, to say nothing of its disapproval of violence, torture, horror, and the gruesome, the Spectre finally dwindled to a mere shadow of the pitiless avenger he had been at his creation.

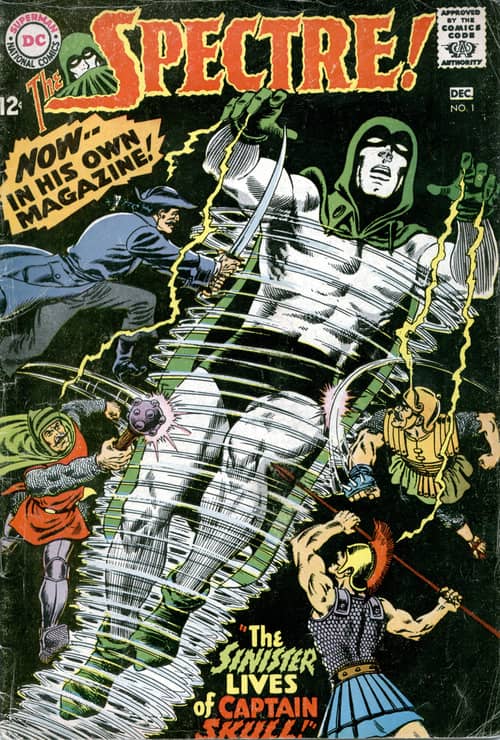

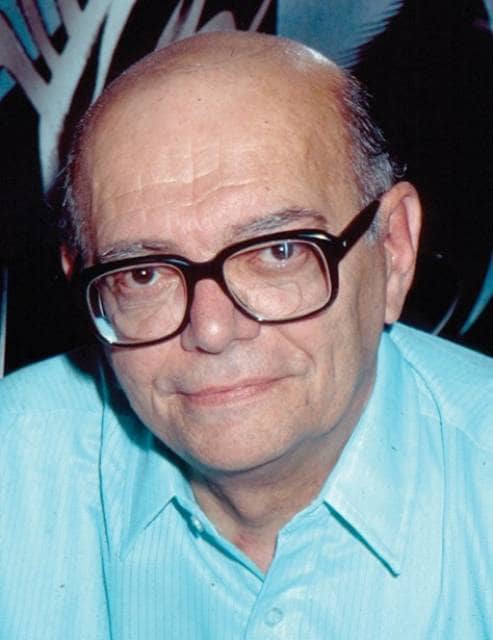

Michael Fleisher

By the late Silver Age, the character was relegated to an occasional listless “guest” appearance in someone else’s book, and the abject failure of his own magazine seemed to mark the Spectre’s final dead end. By the last issue he wasn’t even participating in any of the stories, instead acting as a sort of master of ceremonies, providing a quick introduction to toothless tales of the supernatural and then getting out of the way. Jim Corrigan was probably relieved; maybe now he could finally pack his bag to go fishing and leave cleaning up crime to all those goody-two-shoes in the Justice League.

All that changed with Adventure 431. Michael Fleisher (who died in February of this year) had previously scripted a handful of stories for DC, mostly for House of Mystery and House of Secrets, conventional work that drew little notice. With the Spectre, though, he let it rip, restoring the character to his early identity as a malicious entity of limitless wrath and merciless vengeance. In Fleisher’s hands, the Spectre’s lack of anything resembling human sympathy, understanding, or self-doubt results in acts of “justice” that are more appalling than any criminal outrages committed by the Joker or Lex Luthor on their worst days.

In the Spectre’s universe, there is no compassion or forgiveness, and no possibility of reform or redemption; there are no excuses, mitigations, or misunderstandings, and most disturbingly, there are absolutely no limits beyond which punishment cannot decently go. Though he was one of the original members of the Justice Society in the forties, the Spectre never fit in very well with other “superheroes” in any of his incarnations, and least of all in the Fleisher/Aparo version, in which he is less a hero than an inhuman embodiment of insatiable, demonic rage. Fleisher and Aparo’s character is fitter for the grim universe of the EC horror comics of the fifties, in which extreme transgressions are inevitably followed by outlandish retributions, than he is for any world that also holds cheerful types like the Atom or Green Lantern (even the Batman of that era had yet to force a child to eat a rat.) Of course it was the excesses of EC that brought on the Comics Code in the first place.

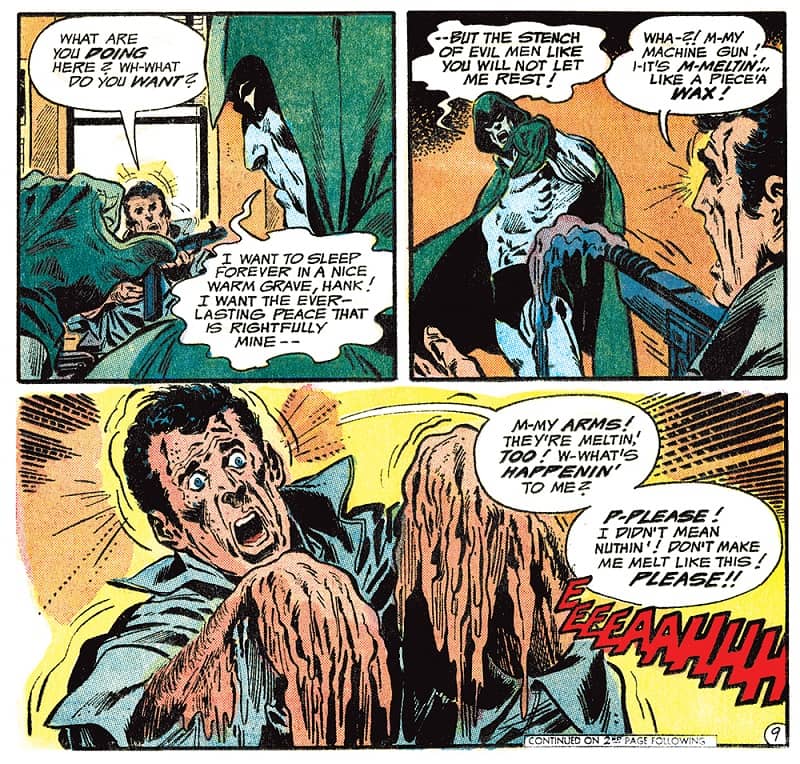

The difference between other heroes and the Spectre becomes immediately apparent in that initial 1974 Adventure appearance, where the he gets the ball rolling by luring a car off a cliff. The vehicle bursts into flames, and the restless spirit impassively listens to the shrieks of the burning driver (admittedly a murderer) before moving on to his next “appointment,” where he corners a crook and causes the terrified, pleading man to melt like wax, leaving a sentient, still-screaming puddle. The Spectre finishes the story by turning another bad guy into a skeleton, perhaps in homage to his very first act of vengeance, all the way back in More Fun Comics 53 (oh, the irony of that title!) in March 1940.

In subsequent Adventure stories, malefactors are instantly aged into ancient, withered ruins, dragged into open graves by leering ghosts and buried alive, and in perhaps the Spectre’s favorite maneuver, turned into various things (and Aparo always makes it clear that the evildoers retain their human consciousness through all of these appalling transformations) — sand, glass (which shatters), wood (which is sliced up with a band saw), a mannequin (which is incinerated in a bonfire).

The Spectre is also fond of enlisting animal aid. Various criminals are eaten alive by a giant squid, tossed into an alligator pit, ripped to pieces by stuffed gorillas that the Spectre animates for the purpose, crushed by spectral snakes, and a hood nicknamed “Ducky” (for his endearing habit of punctuating his pronouncements by squeaking a child’s rubber duck), is even eaten by his own toy, which the Spectre causes to swell to an enormous size, complete with a correspondingly large appetite for human flesh.

In what is perhaps the most notorious incident of the Fleisher/Aparo run (it’s the one everyone seems to mention first, anyway), the Spectre punishes an evil hairdresser (there have to be ten thousand jokes I could make here, but I think I’ll let it go) by cutting the man in two with his own supernaturally enlarged scissors.

Granted, these people are all Evil with a capital E, but this is still strong stuff, and it’s made all the stronger by the fact that none of the Spectre’s victims tough it out. (Criminals though they are, victims seems the only appropriate word for them.) The targets of the Spectre’s retribution all die terrified, screaming, begging for mercy, pleading for their lives. How these stomach-wrenching stories made it past the Comics Code Authority — which still had some teeth in those days — I’ll never know.

Fleisher’s transgressive scripts are only half of the reason these stories are qualitatively different from their Golden Age models. An equally important difference this time around is the art of Jim Aparo, one of the most underrated comic creators of his era. The only major DC character he ever helmed for any length of time was Batman, and he spent large chunks of his career delineating fringe or offbeat characters like Aquaman, the Phantom Stranger, and, of course, the Spectre.

Much of even the best Golden Age art has an unfinished, amateur feel about it (it’s one of the era’s charms); words and image alike are often so sketchy that character and action barely register. But Aparo’s art is unfailingly slick and professional, in the best sense of those terms. He had a way with violence and a gift for depicting cruel, corrupt characters; one look tells you his villains are rotten to the core. They would have to be, to make the Spectre’s tactics even minimally acceptable, and Aparo’s talent for depicting these vile people in extremis was exceptional; when they’re machine gunning innocent bystanders their vicious glee is evident in every line, and when they’re being burned, sliced, shattered, or devoured, their fear and agony go right to a reader’s gut, and gives these stories an undeniable, disquieting power.

Jim Aparo

The Spectre stories that appeared in Adventure 431 to 440 caused quite a stir; a lot of people objected to them, both outside the comics industry, and even within it. What shortened the run probably had nothing to do with protests or pressure, however. It was likely more due to the fact that a character as extreme as Fleisher and Aparo’s Spectre is inherently self-limiting. (Fleisher suggested as much when he said, long afterward, that after a year or so he just started to lose interest.) When you begin by incinerating and melting people, there’s nowhere to go — nowhere any decent person would be willing to follow, anyway. If the series had continued with its logic unaltered, eventually the Spectre would have wound up crushing jaywalkers under the spike-studded wheels of monster trucks and stuffing folks who sneak sixteen items into the express line at the supermarket into giant paper shredders.

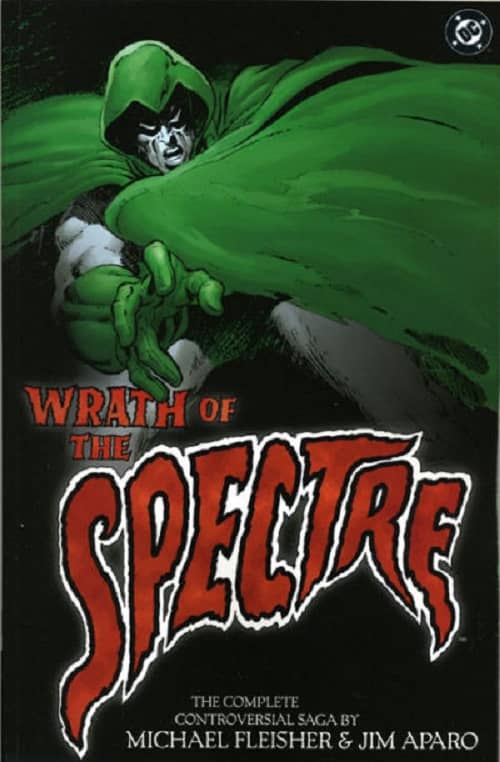

That last one might seem like justice of a sort (at least from the perspective of the guy behind the guy with the extra items), but a vengeance so unfettered that it commits acts even uglier than the original crimes, all in service of a justice that forgets that everyone crosses the line sometimes… well, it’s problematic, to say the least, even in the morally flattened world of comic books. The Fleisher/Aparo Spectre was bound to wear out his welcome sooner rather than later… say, after about ten issues. In a nice irony, that’s just how long the suffocatingly bland 1967-69 Spectre comic book lasted. One run expired of ennui, the other of excess, but the more extreme iteration is at least remembered, because it really shook things up while it lasted and generated aftershocks that are still felt in comics to this day.

The Spectre that haunted the pages of Adventure in 1974 and 1975 is an important landmark in comics’ progression from a children’s medium to a more adult one, and the work that Michael Fleisher and Jim Aparo did on the character remains the most important since the Spectre’s original appearances almost eighty years ago. They produced stories that are still striking and startling; there was nothing like them when they appeared in the mid 70’s, and there’s not a whole lot like them even today – for good reason. Their flavor is intense and unique and not wholly pleasant, and the very narrowness that made them so bracing also ensured that they would be unable to maintain their appeal over a long run. They’re not easily forgotten, but ultimately so bold a dish serves better as an appetizer than as a meal.

But the next time you see some able-bodied jerk park in a handicapped space, or you’re kept awake on a work night by a thoughtless neighbor’s loud party, you may be forgiven if you find yourself wishing that Jim Corrigan could return from wherever he may be, in this world or the next, and as the Spectre, pay just one more visit…

“I’ll… I’ll turn down the stereo, I promise! Just go away!!” “Look into my eyes, evildoer, and see your fate!” “No… no! Please! EEEAAHHHHH!!” And the inconsiderate partier vanishes, replaced by a living piñata with a terrified human face, to be helplessly battered to smithereens by an eerie army of giggling, ghoulish children…

Fleisher and Aparo got one thing right. Sometimes, mercy and compassion are for the birds; like Jim Corrigan, you just want to get some sleep.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Perfect Dream of Summer: The Mad Scientists’ Club.

Very entertaining article. I’ve read a good chunk of SA Marvel (thanks to Marvel Unlimited) but i’ve only dipped my toe into DC backlog (only adam strange, suicide squad, and challengers of the unknown.)

I’ve never heard of this run. But i would love to read one or two issues.

Thanks for the review of Golden Age spectre. I, being a younger fan, followed him during the 80s post-crisis recreation. Knew of his golden-age legacy but not going to ask the parents for $600 for each issue to pay Comic Book Guy… He was killed during the crisis but then ressurected with far less power – essentially the world’s most powerful ghost but still tied to Jim Corrigan who worked as an unliscenced Private Eye – himself along with his Ghostly friend/fiend an “Intruder” from a universe no longer in existance. Even with limited powers the Spectre managed to carry on his horrific revenge against evil – “like a horror show vigilante” – though they finally dealt with how horrific his acts were.

As far as the “Code” issue – it’s like the MPAA ratings system – yeah they have authority but how many “Customers” do they have? And if they decided “How DARE the Government interfere with our First Amendment rights!?” and just pay more for lawyers and lobbyists… So the Code was good to create an expensive and unfairly strict barrier to push out outsiders but then rubber stamp most of the stuff the publishers put out, long as not too extreme. Good riddance to the ‘comics code’.

To Glenn–the Adventure run was reprinted in a four issue series titled Wrath of the Spectre with I believe two unpublished stories that were completed but never published. The adventure run isn’t too hard to find but I have noticed the prices going up for them. John Ostander still the best run overall in the 80s and well worth a look see.

This run also sparked a lawsuit between Harlan Ellison and Fleisher when Ellison, in a Comics Journal interview, called Fleischer “fucking crazy” or something along those lines. Apparently he meant in a complimentary way but Fleisher took offense and sued Ellison for libel.

The exact terms Ellison applied to Fleisher were “certifiable” and “bugfuck.” He followed them up by saying something to the effect that he was probably approaching libel. And yes, he actually meant to be – sort of – complimentary. Fleisher lost the suit.

Just another stop on the madcap caravan that was the life of Harlan Ellison.

Terrific article! I was only a wee lad in the last 70s when I bought a used copy of Adventure Comics presents THE SPECTRE at a garage sale for a either 10 or 15 cents–it was quite a bargain for a poor kid at the time, especially when the cover price was 25 cents (even for an issue that was years old, like this one). I knew right away it was a special comic–better than the other back issues I’d picked up for a few nickles and dimes. It was the Spectre, but it was Jim Aparo’s art that made this humble little comic book feel like a blockbuster movie experience–but there had never been anything as far-out and phantasmagorical as these issues put on the silver screen at this point in cinematic history. In the 70s, comics “special effects” were still faaaar ahead of movie special effects. It’s one of the things that made comics so magical and amazing. Anyway, over the years I’ve tracked down ever issue of this run–and it’s still a sheer pleasure to read it again every few years. This article shows the whole thing in a new light, and it made me realize for the first time how radical these issues were FOR THEIR TIME, something that was lost on me as a child. But it makes perfect sense–the seventies is when comics started getting wild again! My favorite horror comics usually come from the late 60s, early 70s. The only comics run that might–just might top Jim Aparo’s work on this SPECTRE run is his legendary PHANTOM STRANGER run. The world mainly remembers him as a BATMAN artist, but that’s slowly changing as more of his classic work gets reprinted. (Still waiting for a full-color reprint of that PHANTOM STRANGER run!!!) Thanks for the great article, Thomas!

Any lover of the Aparo Spectre is advised to seek out a copy of House of Mystery 201 (April 1972). There’s a story in it, “The Demon Within,” written by Joe Orlando and John Albano, with Aparo art, that’s one of the most chilling things you’ll ever read.

Yes! I read “The Demon Within” story when I was WAY too young to grasp the full horror of it, and it still blew my mind and gave me the creeps–as it was intended. I was probably the same age as the kid in the story. Freaky, and it still is. (I’m pretty sure I read it in a reprint issue, late 70s.)

Read somewhere once (maybe in a forward in Wrath of the Spectre or some Back Issue mag) that the editor of the Jim Aparo run never once looked at the Spectre pages in Adventure. So it was long into the run that the powers that be of DC learned of the shocking content and then canceled it immediately. Think perhaps the same with the CCA happened as well. Had the editorial and CCA process been applied as it had meant to work, those comics would not have been printed.

i was 12 in 1974 and in the 7th grade when i first discovered the spectre. i had never seen anything like it previously. i was used to the boy scout type superheroes, but this … this was something completely different. this was truly shocking to me. it was also very appealing. it was like super-hero and horror comics all in one! around the same time i discovered dc’s mid-70’s run on the shadow; another character that took great glee in the dispatching of criminals. both titles made a huge impression upon me. they set the bar very high for the anti-heroes to come. i have since read that fleisher actually either took all or most of the deaths in the spectre’s run in adventure comics from old 50’s horror comics. i can not however confirm if ths is factual or not. the phantom stranger, the shadow and the spectre often used something along the lines of ‘men/mortals call me …’ as their introduction to evil doers. i totally agree with you about jim aparo’s art. when i started collecting he very quickly became my very favorite comic book artist.

You know, I read the Michael Kaluta Shadow back when I was reading the Fleischer/Aparo Spectre and loved it to excess, but when I was writing this piece, I never made the connection between the two! Thanks for pointing out what was too obvious for me to see – maybe I’ve found the subject for my next piece…