Fantasia 2018, Day 7: Cam

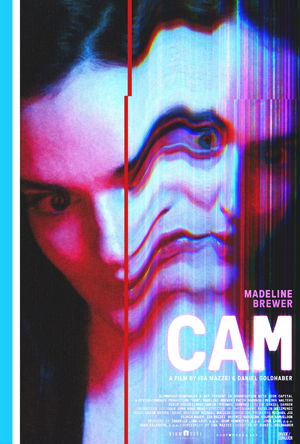

The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion.

The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion.

The first thing that must be said about this film is that it is structured perfectly. It’s only 94 minutes long, but it gets across a lot of information and introduces us to a lot of characters — Alice’s friends and rivals among her co-workers; some of her customers; and her family (who don’t know what she does for a living). The plot’s laser sharp: we spend the first third learning about Alice’s life as a performer, getting to understand the environment, and seeing how she plans her shows for the sake of getting her clients to give her tokens which move her up the ranking of women on the webcam service. Then she loses control of her account, and has to find out what’s going on, and her actions are exactly what you’d expect — talking to her friends, suspecting her rivals, trying to deal with the company, trying to report her problems to the cops (who don’t understand, and one of whom tries to hit on her). This is a mystery, and her investigation gets more and more desperate, setting up the final third of the film in which there’s another slight shift of genre as Alice finds out what’s happening and tries to deal with it. The ending’s unexpected, tense, and thoroughly solid.

It is probably worth noting — as it was in the Fantasia program — that Mazzei’s a former camgirl, meaning that she’s writing from a place of knowledge. Issues relevant to sex workers (as when Alice’s family finds out what she does, and the consequences that follow from that) are used well, and the depiction of Alice’s job is appropriately everyday: it’s a job, with things she likes and things she doesn’t, and some co-workers she gets along with and some she doesn’t, and regular customers good and bad, and all the rest of it. I don’t think the film’s especially celebratory of the work, but one does get a bit of a sense of why Alice keeps at it: she has an outlet for her creativity and performative drive.

Performance, in fact, is key to this movie. It is I think a film about the way in which people are always performing, and contrariwise also about the way in which we parse what is real and what’s pretend. At one point Alice meets a client in a tacky Mexican restaurant: “I like authenticity,” he brags, and “I see right through the glitz.” In fact it’s clear from context he can’t even see through himself; he’s performing a role in his own head, and trying to convince Alice of its reality. Alice herself effectively lives off of her ability to write and act. The film begins, unnervingly, with her apparently committing suicide live on webcam; then it turns out it was all staged, all a play, for the approval of her audience. The progress of the film is in many ways a stripping away of artifice until Alice is left with an uncomfortable reality.

Performance, in fact, is key to this movie. It is I think a film about the way in which people are always performing, and contrariwise also about the way in which we parse what is real and what’s pretend. At one point Alice meets a client in a tacky Mexican restaurant: “I like authenticity,” he brags, and “I see right through the glitz.” In fact it’s clear from context he can’t even see through himself; he’s performing a role in his own head, and trying to convince Alice of its reality. Alice herself effectively lives off of her ability to write and act. The film begins, unnervingly, with her apparently committing suicide live on webcam; then it turns out it was all staged, all a play, for the approval of her audience. The progress of the film is in many ways a stripping away of artifice until Alice is left with an uncomfortable reality.

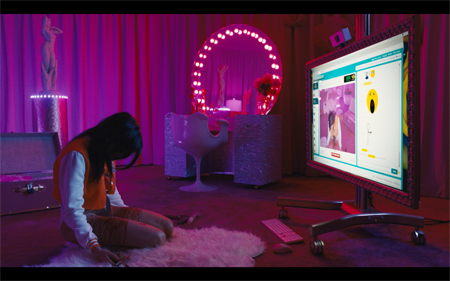

But for this to matter we have to understand how thoroughly constructed her reality is. Here the movie’s visual sense is important: Alice has constructed a room for her shows, lined with pink curtains and mirrors and lights, and if it’s a very low-rent sort of glamour, it’s still visually effective and on film even striking. What Alice does in that space is, in almost every way, a performance. We see her begin a show mentioning as an aside that she needs to pee, then later she opens another show with the same comment, and then we realise that the apparent aside is part of her act. Early in the movie, after the staged suicide, she leaves her set to tidy up, chatting over the computer with one of her clients — and though it’s relatively relaxed, it soon becomes clear she’s still performing.

This is a film about the way one performs one’s selfhood, then, but also about the way in which one monetises the self in the current electronic world. About the trail of information we leave online. About constructing a self as a kind of competition. Eventually, I think, it’s about insisting on the self we choose for ourselves. And about technology: my suspicion is that any movie about the internet as it now is will soon feel like a period piece, but if a period piece is well done, that won’t matter. This is a movie that speaks to how the present moment feels, technologically and sexually and socially.

This is a film about the way one performs one’s selfhood, then, but also about the way in which one monetises the self in the current electronic world. About the trail of information we leave online. About constructing a self as a kind of competition. Eventually, I think, it’s about insisting on the self we choose for ourselves. And about technology: my suspicion is that any movie about the internet as it now is will soon feel like a period piece, but if a period piece is well done, that won’t matter. This is a movie that speaks to how the present moment feels, technologically and sexually and socially.

I mentioned the pink-and-mirrored space Alice constructed for herself, and how distinctive it looked — it wasn’t until well after the movie ended that I thought of that other famous Alice and her looking-glass. But the directing and cinematography’s also quietly effective at incorporating Alice’s computer screen. We see what she does, and try to make sense of it alongside her. We are with her as she chats by Skype or text with her clients; we see the particular interaction of this performer and her audience. Alice lives for the validation (and money) the tokens provide, hoping to rise in the camgirl rankings, but it’s not until the false Alice starts breaking her rules that she really begins to take strides toward the top. There’s authenticity there, but it’s authenticity from a fake. The movie’s clever enough, literate in its unusual way, that it can use a paradox like that as a way to illustrate its themes.

It’s perhaps worth mentioning that there’s little explicit sex or nudity (not none, but little) on screen, although there’s much discussion of sex. Here as in many other ways the film uses implication effectively. And strong acting performances, especially from Brewer, who builds her character’s strength effectively and then convincingly shows her pushed to the edge of her sanity.

It’s perhaps worth mentioning that there’s little explicit sex or nudity (not none, but little) on screen, although there’s much discussion of sex. Here as in many other ways the film uses implication effectively. And strong acting performances, especially from Brewer, who builds her character’s strength effectively and then convincingly shows her pushed to the edge of her sanity.

Cam is a well-played, well-shot, exquisitely-written film. Netflix has bought the rights to it, so it should appear on the streaming service at some point in the not too distant future. How much of a barrier the sexual content of the film will be must depend on the individual viewer, I suppose; I can only say for myself I didn’t find it either confrontational or unearned. From my perspective Cam’s a remarkable success.

After the movie, director Daniel Goldhaber and writer Isa Mazzei came out to take questions, along with various members of the movie’s production team and crew (my record of their answers comes, as usual, from handwritten notes). Asked how they worked together, Mazzei said “We yell a lot,” and said that she and Goldhaber had met in high school. She produced his first play, and then when she worked as a camgirl she turned to him to direct some of her videos. He did a good job, and so she turned to him again when she wanted to do a feature film that she hoped would get people to empathise with camgirls and normalise the profession. They discussed making a documentary before deciding that a genre film was the best approach.

Asked how they came to work with Brewer, they said they’d had a problem getting an actress because agencies would not send the script out due to the content. Even in cases where they’d described or pitched the concept to an actress who showed interest, their agency sometimes didn’t send them the script. No-one knew Goldhaber or Mazzei. As it turned out, Goldhaber’s father saw Brewer in an episode of Black Mirror and insisted she’d be perfect in the role. This led to nagging her agent until she was sent the script, and eventually to casting her. A question followed on Samantha Robinson (of The Love Witch), who played a supporting role, and how they’d wanted her character’s performances to be over the top.

Asked how they came to work with Brewer, they said they’d had a problem getting an actress because agencies would not send the script out due to the content. Even in cases where they’d described or pitched the concept to an actress who showed interest, their agency sometimes didn’t send them the script. No-one knew Goldhaber or Mazzei. As it turned out, Goldhaber’s father saw Brewer in an episode of Black Mirror and insisted she’d be perfect in the role. This led to nagging her agent until she was sent the script, and eventually to casting her. A question followed on Samantha Robinson (of The Love Witch), who played a supporting role, and how they’d wanted her character’s performances to be over the top.

Asked whether Mazzei found herself being patronised due to a prejudice against sex work, she said she found that there was an assumption that once you’d done sex work that made it impossible for you to do anything else. She declared that she’s worked in tech, retail, and porn, and had never been as harassed as in the film business. Asked about the exact nature of the duplicate Alice in the film, Mazzei observed that this had to do with the theme of identity and the fracturing of identity, and about how our digital selves get away from us.

Asked about the writing process, and whether her own experiences had informed it, Mazzei said yes, like Alice she’d had one of her viewers move to her home town. She put some of her own insecurities in Alice’s story, such as worries about her family finding out about the job before she was ready for it. She translated these worries to fiction, and had Goldahaber to help dig them out. Goldhaber observed that they worked out the narrative, then interviewed other sex workers and customers to make the story universal, to be sure what they depicted wasn’t Mazzei’s experience alone.

Mazzei was asked about the scene where Alice’s mother finds out about her daughter’s work and cautiously gives her support, and whether this matched her experience. Mazzei said her mother was in fact in the audience, then said the scene was largely pulled from her experience, showing a mother who was accepting but trepidatious. The actress rewrote some of the lines, knowing exactly what she wanted in the character and so bringing her own experiences as well.

Mazzei was asked about the scene where Alice’s mother finds out about her daughter’s work and cautiously gives her support, and whether this matched her experience. Mazzei said her mother was in fact in the audience, then said the scene was largely pulled from her experience, showing a mother who was accepting but trepidatious. The actress rewrote some of the lines, knowing exactly what she wanted in the character and so bringing her own experiences as well.

Asked if she’d had to keep up to date with security measures, Mazzei said people approach security in different ways; she described herself as paranoid in using fake names, towns, and so on. Goldhaber observed that she was kept anonymous on the script, as it was being sent around Hollywood, and that there was concern that her security would be compromised. Asked about the inspiration for Alice’s staged suicides, Goldhaber talked about how the script had always begun with a suicide, setting up a slightly fantastic version of the cam world, a heightened reality as in Black Swan. It was meant to establish Alice as an artist in her own way.

Asked whether the film should be taken as being in part about the gig economy, Goldhaber said it totally was, as well as being about sex work and digital identity; they were trying to treat Alice as a YouTuber. He spoke about how the idea of a digital identity was a narrative tool inside the genre story, that it’s everything about oneself — creativity, sexuality, and friends — wrapped into one. In terms of Alice’s job as a job, they hoped in the first half-hour of the film to get the audience trained to be excited at the sound the computer played when she gained tokens, as one celebrates getting paid.

The creators were asked about working with Blumhouse Productions, who co-financed the movie, and they said Blumhouse told them they’d responded to the power of the script, that the company thought it was a great product telling an important, timely story; they observed that Blumhouse was above-board in all their dealings (something not necessarily the case with other companies). Asked about the contrast of Alice’s shows and her off-camera life, Goldhaber pointed out cinematographer Katelin Arizmendi and editor Daniel Garber, and spoke about treating the cam scenes like a musical number or an action scene. The aim was to make the cam scenes exciting, with lots of edits and multi-camera set-ups. Producer Isabelle Link-Levy spoke about creating a web site for the film to use (which was actually briefly live), and scripting the chats with Mazzei, coming up with personalities for all of the customers whose texts appeared, however briefly, on screen. The chats were live so Brewer had something to work with. (Link-Levy also mentioned the difficulty of framing shots in Alice’s room so a camera wasn’t in the shot.)

The creators were asked about working with Blumhouse Productions, who co-financed the movie, and they said Blumhouse told them they’d responded to the power of the script, that the company thought it was a great product telling an important, timely story; they observed that Blumhouse was above-board in all their dealings (something not necessarily the case with other companies). Asked about the contrast of Alice’s shows and her off-camera life, Goldhaber pointed out cinematographer Katelin Arizmendi and editor Daniel Garber, and spoke about treating the cam scenes like a musical number or an action scene. The aim was to make the cam scenes exciting, with lots of edits and multi-camera set-ups. Producer Isabelle Link-Levy spoke about creating a web site for the film to use (which was actually briefly live), and scripting the chats with Mazzei, coming up with personalities for all of the customers whose texts appeared, however briefly, on screen. The chats were live so Brewer had something to work with. (Link-Levy also mentioned the difficulty of framing shots in Alice’s room so a camera wasn’t in the shot.)

Asked about the lighting, Goldhaber said he didn’t understand lighting and (according to my notes) Arizmendi spoke about distinguishing between the real and cam worlds by using more surreal lighting in the cam world. There would always be an overpowering source of light from the computer screen, Poltergeist-like. She talked about the difficulty of lighting and shooting the pink room differently for different scenes, and of using lighting to create other colours in it. Link-Levy noted that shooting seven days in the pink room drove them all nuts; after working in an environment with pink everywhere, when they walked out of it the rest of the world looked green. Finally, asked if they’d collaborate again, the creators enthusiastically said yes.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

While I agree with much of what you say, I feel that the script short-changed the viewer with its ambiguity concerning the development of the (detached, “evil”) alter-ego. I personally wondered whether “Cam” was also a meditation on the dangers of AI, as a deep-learning artificial entity was the only reasonable explanation for the new and completely artificial Lola. (I happened to be approached by one of the fellows involved in the script who was glad to hear that theory.)

I wanted to immerse myself into the world of “Cam”, but ultimately the film-maker’s non-committal approach to delineating the mystery frame-work left me feeling non-committal about the movie.

I didn’t mind the ambiguity. I felt (er, SPOILERS for this comments section, I guess) that what was happening was supernatural — the way Tink talked about the thingy and the way it operated, it felt like a 21st-century spirit at work. Although AI makes just as much sense. I dunno, I suppose I felt the point of the movie was about Alice, so I didn’t feel I was missing anything by not knowing exactly where the monster was coming from. I knew what it did, and that was enough.