Fantasia 2018, Day 5, Part 2: Mega Time Squad and I Have a Date With Spring

Monday July 16 was an odd day, beginning with the neorealist neo-noir Neomanila and going off in different directions from there. First would come a time-travel comedy from New Zealand, Mega Time Squad. Then a movie that was a kind of pre-apocalyptic film, I Have a Date With Spring, from South Korea. The directors of both the two later movies would be present to take questions.

Monday July 16 was an odd day, beginning with the neorealist neo-noir Neomanila and going off in different directions from there. First would come a time-travel comedy from New Zealand, Mega Time Squad. Then a movie that was a kind of pre-apocalyptic film, I Have a Date With Spring, from South Korea. The directors of both the two later movies would be present to take questions.

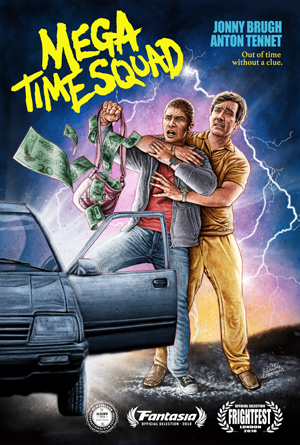

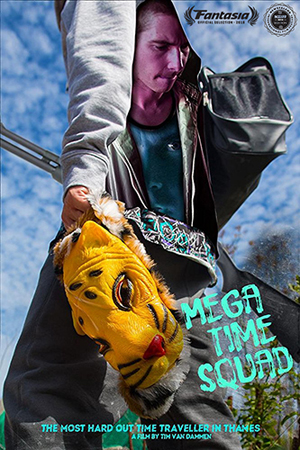

The director and writer of Mega Time Squad is Tim Van Dammen. His movie’s about Johnny (Anton Tennet), a loutish but somewhat good-hearted drug dealer in the small New Zealand town of Thames. Alongside his best friend Gaz (Arlo Gibson), Johnny works for the nearest equivalent to a crime lord around, a self-important short-tempered kingpin named Shelton (Jonny Brugh, from What We Do in the Shadows). Ambition leads Johnny to make a try for money being held by a Chinese antique shop owner, which in turn leads to him stealing a Mysterious Item from the shop. The Item turns out to be a limited time machine — once activated, it causes Johnny to return to the same place and time on every subsequent use. Johnny, now on the outs with Shelton, makes a series of bad choices and uses to the Item to bail him out each time, eventually gathering a group of temporal duplicates of himself: the Mega Time Squad. But can he settle things with Shelton, and the Chinese man now hunting him down? And is there any truth to the legend that a vengeful demon will strike down whoever wields the Item?

This is an amiable (if profane) film, clever yet not over-complicated in its temporal mechanics. There’s nothing epic about it at all, and in this case that’s to the good. You don’t feel the stakes are overblown at all, or even especially high — technically Johnny’s life is at stake, but the guys in Shelton’s gang don’t feel like killers; legbreakers, maybe, but not killers. Shelton himself, as played perfectly by Brugh, doesn’t seem the sort to take responsibility for a murder. This is fine, as the result is that the level of danger’s enough to keep things moving but not enough to outweigh the humour.

The time-travel element’s explored in reasonable depth, but doesn’t feel exhaustive. It’s a driver of action, not a thing to be developed for its own sake, and that’s about right. There are a couple of spots (notably in terms of how some of Johnny’s duplicates show up in a particular place) that are a bit confusing to me, but this is a time-travel film, and it’s possible a second viewing would clarify the plot mechanics — which anyway are less important than the general drift of the action. And that’s always clear.

There’s a straight-faced quality to the film that sits well with the general surreal tone. This is a smart movie about stupid people, but the stupid people have a kind of shared reality of their own in which their stupidity makes a kind of sense. It’s consistent stupidity, and the film maintains that consistency of tone. The actors do good work here, making their characters credible on their own terms. In a very general way the movie’s a little like Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, in the mix of time travel with a kind of low-key pleasant approach and characters who are much less intelligent than the film itself.

There’s a straight-faced quality to the film that sits well with the general surreal tone. This is a smart movie about stupid people, but the stupid people have a kind of shared reality of their own in which their stupidity makes a kind of sense. It’s consistent stupidity, and the film maintains that consistency of tone. The actors do good work here, making their characters credible on their own terms. In a very general way the movie’s a little like Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, in the mix of time travel with a kind of low-key pleasant approach and characters who are much less intelligent than the film itself.

In particular, Anton Tennet’s Johnny anchors Mega Time Squad. The movie doesn’t work unless he’s likeable, and since at the start of the film he’s a low-grade drug dealer who wants to become a crime boss, that’s a bit of a challenge. As the movie goes on, though, he slowly grows. The overall level of ‘bad stuff Johnny goes through’ to ‘level of empathy Johnny shows for others’ works, I think, and in a film that has an undertone of solipsism — his Mega Time Squad is only himself multiplied — him beginning to understand that the world has other people in it gives the story a useful theme.

At the same time, there’s also a more obvious moral about greed, as the demon that supposedly tracks down time travellers is a demon of greed and gluttony. This manages not to be too overstated. It’s there, and works with Johnny’s character growth, but I didn’t feel it was really the key of the movie. Similarly, Kelly (Hetty Gaskell-Hahn), Shelton’s sister and Johnny’s love interest, has a few quirks but doesn’t feel like a fully-developed character in her own right. I don’t know that I’d call her an object to be won, but there’s something of a limit to her agency through most of the movie, and I never quite grasped what drew her to Johnny — who much of the time seems to exasperate her, and with good reason.

Otherwise, though, the script’s solid, not just in terms of story but dialogue. The language is interesting, and the gags are delivered with solid timing. It’s relatively unpredictable, too, with threats looming, disappearing, and returning in surprising ways. It makes good use of both crime tropes and time travel as sources of humour, as well as playing the one off against the other.

Visually, it’s a solid enough film. Exterior shots, particularly some in a cemetery up a hillside from Thames, capture a sense of a wide-open outdoors; interior shots seem to always show cramped, small rooms in which characters are bumping up against each other. I don’t know if that’s deliberate, but it seems to mirror the narrow world Johnny’s caught up in and his eventual search for something larger, so I’ll say it works.

Mega Time Squad is a solid movie. It’s a modest film, almost self-consciously so. It doesn’t have especially high ambitions, but what it does have it fulfills. It’s a clever, tight comedy that tells a reasonably complex story in only 86 minutes. There’s value in that, and no little craft.

Mega Time Squad is a solid movie. It’s a modest film, almost self-consciously so. It doesn’t have especially high ambitions, but what it does have it fulfills. It’s a clever, tight comedy that tells a reasonably complex story in only 86 minutes. There’s value in that, and no little craft.

After the film, Tim Van Dannen came out to take questions. The first was about the writing process, and how he came up with the film’s rapid-fire dialogue. Van Dannen said he spends a lot of time with his Dad, who lives in the actual small New Zealand town of the film, Thames, which he described as just big enough to have a supermarket, a hospital, and a parole office. He spoke about trying to emulate the rhythm of the language. He noted that there was no room for ad libbing in the film because of all the planning needed to have his lead actor interacting with himself. He said he’d tried to give each member of the Mega Time Squad some kind of individuality depending on how many times they’d jumped through the loop and how jaded they were. And he said it was difficult to block scenes with one actor who’d be playing multiple roles in a scene; he had to shoot a lot of the scenes with his lead actor on his iphone in order to work out the blocking before shooting it for real. It naturally took a lot of rehearsal.

Then there was a question about Mega Time Squad’s connection to the Power Rangers, and Van Dannen said that one of Shelton’s thugs, Damage (Milo Cawthorn), played the Green Power Ranger in one iteration of the franchise. To a question about one why another of Shelton’s men was always reading something, Van Dannen said they’d had a backstory in mind for the character in which he’d had enough of the criminal life and wanted to be an airline pilot, so was always studying. Van Dannen recalled that when they were filming in an actual house, they’d pull actual books off the shelves, finding titles like Psychic Self-Defense and The Orgasmic Man. Which titles would be read out by Jonny Brugh (Shelton). It was, Van Dannen said, a lighthearted set.

Then there was a question about Mega Time Squad’s connection to the Power Rangers, and Van Dannen said that one of Shelton’s thugs, Damage (Milo Cawthorn), played the Green Power Ranger in one iteration of the franchise. To a question about one why another of Shelton’s men was always reading something, Van Dannen said they’d had a backstory in mind for the character in which he’d had enough of the criminal life and wanted to be an airline pilot, so was always studying. Van Dannen recalled that when they were filming in an actual house, they’d pull actual books off the shelves, finding titles like Psychic Self-Defense and The Orgasmic Man. Which titles would be read out by Jonny Brugh (Shelton). It was, Van Dannen said, a lighthearted set.

Asked how much of a headache it was to script, Van Dannen said it had gone through many iterations. He’d had a success with Romeo and Juliet: A Love Story, a film that was a rap version of Romeo and Juliet, leading many people to send him scripts, before electing in the end to learn to write and make his own script. He said the script was originally about a man who was getting over a breakup, went back in time, ended up sexually touching his past self, then decided to go back again to stop himself. Van Dannen decided he didn’t want to do that and decided to try a crime story as a structure. He found almost at once it was goofy, and demanded to be a comedy.

Asked about the general politeness of the characters to each other, Van Dannen said he definitely liked the idea of the main character always thinking “yeah, fair enough” when caught out. He liked the idea that everyone understood where everyone else was coming from, with vulgarity and politeness both part of it. After a question about the plot, he was asked how long it took to shoot the film; four weeks, he said, in bits and pieces, working around people’s schedules, and using undercover night shoots. Post-production then took ages because of all the FX — he had to build a shot before he could edit it. Asked how he kept track of continuity, he said a lot of the actors looked after themselves.

Asked about the general politeness of the characters to each other, Van Dannen said he definitely liked the idea of the main character always thinking “yeah, fair enough” when caught out. He liked the idea that everyone understood where everyone else was coming from, with vulgarity and politeness both part of it. After a question about the plot, he was asked how long it took to shoot the film; four weeks, he said, in bits and pieces, working around people’s schedules, and using undercover night shoots. Post-production then took ages because of all the FX — he had to build a shot before he could edit it. Asked how he kept track of continuity, he said a lot of the actors looked after themselves.

Asked when it would come out, he said they were talking with North American distributors, but said he didn’t know, that they were stumbling through the wilderness. That was the last question, except for one man from New Zealand who expressed admiration for a joke making fun of the New Zealand city of Hamilton (which, oddly, plays about as well in Canada).

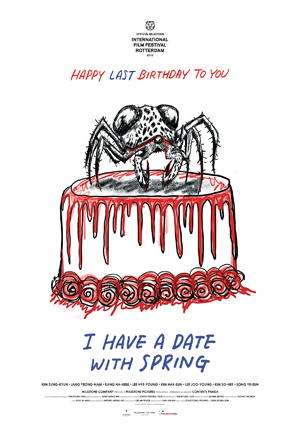

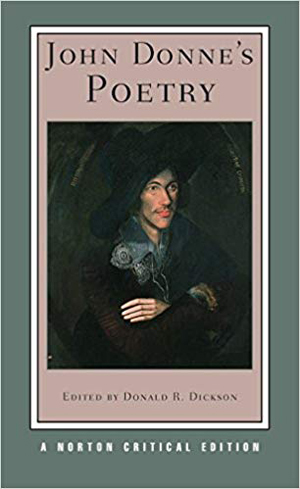

Next came I Have a Date With Spring (Na-wa-bom-nal-eui-yak-sok, 나와 봄날의 약속). Written and directed by Baek Seung-bin, it starts with a movie director (Kang Ha-neul) on his birthday sitting by the shore of a lake, trying to think of ideas for a film he’s been working on for years. An assortment of characters wander by, one of whom is a fan. This leads to the director telling three different stories, each in two parts, each about individual characters on their birthdays, the day before the world ends — when there’s global panic and the streets have emptied, but before the worst has happened. A middle-aged professor (Kim Hak-sun) who studies John Donne meets a dying woman (Song Ye-Eun) and makes a romantic connection; and in the second part of the story we see the cost of this. An artistic schoolgirl (Kim So-hee) who draws monsters in her notebooks meets a strange older man (Kim Sung-Kyun, Kundo: Age of the Rampant) and spends an equally-strange day with him; later we see a sinister gift he has given her. A housewife (Jang Young-nam) who was once a radical meets a fan of her older work (Lee Joo-Young); and then we see how this might lead to violence. A final epilogue with the director concludes the film with some sense of closure.

Next came I Have a Date With Spring (Na-wa-bom-nal-eui-yak-sok, 나와 봄날의 약속). Written and directed by Baek Seung-bin, it starts with a movie director (Kang Ha-neul) on his birthday sitting by the shore of a lake, trying to think of ideas for a film he’s been working on for years. An assortment of characters wander by, one of whom is a fan. This leads to the director telling three different stories, each in two parts, each about individual characters on their birthdays, the day before the world ends — when there’s global panic and the streets have emptied, but before the worst has happened. A middle-aged professor (Kim Hak-sun) who studies John Donne meets a dying woman (Song Ye-Eun) and makes a romantic connection; and in the second part of the story we see the cost of this. An artistic schoolgirl (Kim So-hee) who draws monsters in her notebooks meets a strange older man (Kim Sung-Kyun, Kundo: Age of the Rampant) and spends an equally-strange day with him; later we see a sinister gift he has given her. A housewife (Jang Young-nam) who was once a radical meets a fan of her older work (Lee Joo-Young); and then we see how this might lead to violence. A final epilogue with the director concludes the film with some sense of closure.

This is a well-acted film, particularly on the part of Kim So-hee, and each part of it has a distinct visual identity. At the same time, despite the strong character work and camera work it feels script-driven. This is less a criticism than an observation: this is a film with an odd narrative structure that is as a whole driven by theme and idea. There’s a definite metafictional sense: this is a movie about movies, and about the drive to make movies. On the one hand, the character of the director tells us early on that “we’re all doomed, so let’s go nicely, beautifully,” and then on the other he’s found something like a reason for living by the end of the movie, as implied by the title. The act of storytelling is key here.

And yet the stories he tells are very dark. For all of the film’s overall ambition, each individual tale feels like a sub-par episode of The Twilight Zone — genre tales that build to a twist ending. Each has a first part presenting a fairly delicate yet upbeat kind of emotional equilibrium; each has a second half that seems at first to build on that emotional texture only to undercut it at the end with a vicious twist. That’s a solid idea for a structure, but the twists are sometimes too simple, and seeing them all together tends to emphasise their similarity. Individually, they’re fine. Collectively, they become rote.

This represents the inevitability of death, perhaps: we’re all doomed. But dramatically it feels unsatisfying. Hence, then, the bookend segments with the director. Again, though, I found myself not wholly convinced. Thematically the resolution feels too simple, narratively it feels flat. The movie comes to feel less like a good film than like a good idea for a film. There is, for me, something unearned in the overall sense of inevitable death; something cynical. I felt in the end there was something lacking in the movie’s approach to apocalypse, individual or collective. Death doesn’t feel real. Still, the reason for surviving is more credible, and perhaps the film works as a statement about the importance of storytelling.

This represents the inevitability of death, perhaps: we’re all doomed. But dramatically it feels unsatisfying. Hence, then, the bookend segments with the director. Again, though, I found myself not wholly convinced. Thematically the resolution feels too simple, narratively it feels flat. The movie comes to feel less like a good film than like a good idea for a film. There is, for me, something unearned in the overall sense of inevitable death; something cynical. I felt in the end there was something lacking in the movie’s approach to apocalypse, individual or collective. Death doesn’t feel real. Still, the reason for surviving is more credible, and perhaps the film works as a statement about the importance of storytelling.

Certainly it’s a well-crafted set of tales. The apocalypse(s) are not shown visually, but come to us in drifts of sound overheard on a radio, in images of empty streets. What is key are the character interactions in the nearly-empty world, the connections forged by individuals, and ultimately the personal choices that are made as the world nears its end. There’s a concern in this film with the way that people get fitted into social roles, and especially with the way in which they become outcasts. Each character gets a chance to connect with someone, and in the case of the older two characters, to recover some kind of youthful dream. To become, perhaps, their best selves, if at a cost.

But what comes out of putting these stories together? I feel as though something doesn’t add up, as though the conclusion in some way isn’t properly built up to. As I understand the film, the final sequence with the director isn’t shaped much by any of the preceding stories, and perhaps that’s what I’m missing. Life and art feel detached, such that it’s difficult to see how the first is defined by the making of the second. Which, in turn, seems to be what the theme of the movie is.

But what comes out of putting these stories together? I feel as though something doesn’t add up, as though the conclusion in some way isn’t properly built up to. As I understand the film, the final sequence with the director isn’t shaped much by any of the preceding stories, and perhaps that’s what I’m missing. Life and art feel detached, such that it’s difficult to see how the first is defined by the making of the second. Which, in turn, seems to be what the theme of the movie is.

This is an ambitious film, in any event. I feel all these observations should be understood as tentative; it’s the sort of movie where I’m highly conscious of the fact that a second viewing might cause it to make sense in some way it doesn’t now, and I might suddenly see how the individual parts connect up to each other. Certain aspects of the conclusion suggest that the stories the director tells are things he’s dealing with in the present, as he works on a film he’s been struggling with for three years. But at one viewing, it feels as though there’s a piece missing. As though the simplicity of the individual stories lacks some kind of capstone to round off the whole structure of the movie. It’s still an interesting film, but for me misses being what it promises.

After the movie, writer/director Baek Seung-bin came out to take questions. He was first asked, as a graduate in English Literature, how his studies had affected his cinema. He said that since childhood he’d been a bookworm. He’d especially liked Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and gothic literature in general; he was drawn to stories about the dark side of human nature. A questioner noted that many of the characters in the film were broken, physically or psychologically, and asked what he found interesting about them. He said (in translation, and according to my notes) “I think I am one of those broken people; I like the twisted character I have,” which was represented in his work as dark humour and a dark worldview.

Asked whether it was important to him to twist genres in his films, he said that as a film maniac he likes horror and SF, and in viewing tries to mix different genres. He said he hoped to make Dracula as a Korean film, and recalled words from Park Chan-wook (director of the Vengeance trilogy) who, at a film festival where Park was a jury member, once told him: “May your dark side become darker in much more complex ways.”

Asked which character he most identifies with, he said the junior high school girl. He was bullied in school, and he’d had a hobby of drawing creatures from outer space, which he viewed as his only friends and which made him feel comfortable. The illustrations used in the movie were drawn by him. Asked what the most challenging part of filming was, he said it took four years to finish the film because of the difficulty in finding investors. The scenes with the professor were shot four years ago; the prologue and epilogue of the film were shot last year.

I asked why he used John Donne as the professor’s subject of study, and he said that he’d studied Donne in college along with the Romantics. He spoke of the Mike Nichols film Wit, which starred Emma Thompson in a role she and Nichols co-scripted based on a play by Margaret Edson; Thompson’s character in that movie, a professor who specialised in Donne and who had cancer, inspired the professor character in Baek’s movie. Finally, Baek was asked why he used handheld camerawork so extensively in the film; he said he liked handheld, and thought it was the appropriate technique here to allow the audience to approach the characters more closely.

And that ended the day. It was an odd one, with three very different movies. The next couple days promised a lighter schedule for me, for better or worse, and yet more very different films.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.