Fantasia 2018, Day 4, Part 1: Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura and Aragne: Sign of Vermillion

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.

Sunday, July 15, was going to be my first really busy day of the Fantasia Film Festival. There were four movies I planned to see, with a chance of a fifth, depending on how things worked out. The day’d begin at the Hall Theatre; first, I’d see Destiny: The Tale of Kamakura, a lighthearted Japanese urban fantasy. Then would come Aragne: Sign of Vermillion, also from Japan, a horror anime.

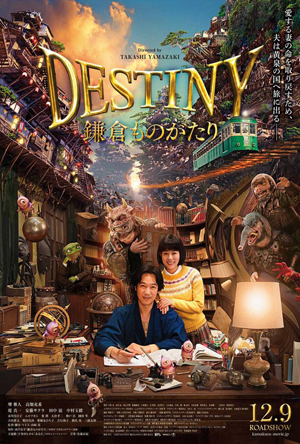

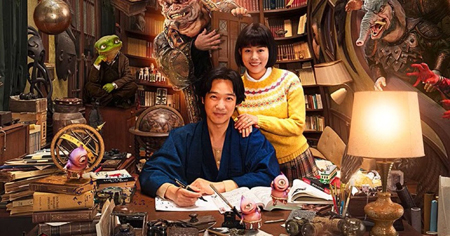

Destiny (Kamakura Monogatari, DESTINY 鎌倉ものがたり) is directed by Takashi Yamazaki, helmer of the Parasyte movies, from a screenplay Yamazaki wrote based on the manga by Ryôhei Saigan. The movie follows Masakazu and Akiko Isshiki (Masato Sakai and Mitsuki Takahata), newlyweds, as they move to Masakazu’s home in the small-but-historic city of Kamakura. Masakazu’s a writer, but Akiko’s plans for their household meet a slight obstacle when she discovers that Kamakura, by dint of being “a magnet of mystical energy for millennia,” is home to any number of supernatural creatures: water imps, death gods, ghosts, bad luck gods, the list goes on. A series of episodic adventures show us different facets of the city and its inhabitants while also deftly advancing the Isshikis’ relationship, finally culminating in an extended otherworldly adventure that brings together subplots unobtrusively introduced over the course of the movie.

This is one of the most purely delightful movies I’d see at Fantasia, and indeed one of the most delightful I’ve come across in a long time. Tonally it’s somewhat similar to the Harry Potter films, in the particular kind of cartooniness of the CGI, in the conscious quaintness of the setting’s historicity, in the way the orchestral soundtrack is consciously lush yet awe-inspiring, and above all in the way that minor details turn out to be pieces of a larger puzzle: the way everything sets up everything else, the way the world feels both expansive and interconnected, perfectly machined in retrospect but almost overwhelming with implications as you live in it. There’s a deeper sense of the folkloric here than in Potter, though. I’ve heard some people mention a feel like a live-action Miyazaki film, and in terms of the creative visual design of the many creatures of Kamakura I can see that. But there’s a clearer bad guy here than is usual in a Miyazaki tale (although that doesn’t become obvious until late in the story).

Still, there’s a similar thrill in storytelling, and an equally unusual sense of structure. For example, Masakazu’s not just a writer but an adviser to the police, and a case he’s called on to solve turns out to have a very close solution to one of the stories in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. But this is not a problem, because the mystery is in fact solved very soon after it’s introduced; yet if it turns out to be an episode with its own quick satisfaction, it’s also a vehicle to set up other plot elements with their own pleasures. Here as elsewhere the film packs any number of sub-stories into its overall tale, creating a world full of incident that miraculously never feels rushed or underexplored, a world full of ideas with just the right emotional heft.

There’s some very fine judgement at work in this movie, just the right amount of cartooniness, just the right balance of comedy and drama. The acting’s spot-on, engagingly artificial, building characters with just the right scale and broadness. The visual sense is equally precise, filling the frame with cluttered but well-composed settings. The movie unobtrusively takes place in a world without cell phones or even computers — probably the 1990s, as dialogue specifically mentions that it’s some time well after 1980, but the point is that the look and feel of this Kamakura is timeless, an old-fashioned but not primitive place. Probably most important to the story, a third-act excursion to a CGI otherworld remarkably does not break the tone, instead feeling like a logical culmination, a follow-through on the mysteries the film has been promising.

There’s some very fine judgement at work in this movie, just the right amount of cartooniness, just the right balance of comedy and drama. The acting’s spot-on, engagingly artificial, building characters with just the right scale and broadness. The visual sense is equally precise, filling the frame with cluttered but well-composed settings. The movie unobtrusively takes place in a world without cell phones or even computers — probably the 1990s, as dialogue specifically mentions that it’s some time well after 1980, but the point is that the look and feel of this Kamakura is timeless, an old-fashioned but not primitive place. Probably most important to the story, a third-act excursion to a CGI otherworld remarkably does not break the tone, instead feeling like a logical culmination, a follow-through on the mysteries the film has been promising.

Some of that, I think, is because the movie’s clever not just in its plot construction but in the way it uses its images. As Masakazu and Akiko drive through Kamakura in an opening montage, we see them pass by a train — and trains become a recurring motif in the film. Masakazu builds model trains. The spirits of the dead leave the town once a day on a special supernatural train. The solution to the Holmesian mystery involves a train. And so the fact that we get an ending in which a train features prominently leaves us satisfied: whether we notice it consciously or not, the image has been developed and in some sense perhaps resolved.

Mostly, though, the unity of the film comes through the unobtrusive but consistent character development. In the early minutes of the film there’s an almost sitcomish feel to the movie, as Akiko tries to keep Masakazu’s editor (Shinichi Tsutsumi) from finding out that Masakazu’s assignment isn’t done; she fails, though, and this ends up enhancing our sympathy for all three characters, who react less dramatically than we might think. All of them end up playing significant roles in the film, and their movement through the episodes, what we learn and how we see them change, makes the story feel like a cohesive whole.

Mostly, though, the unity of the film comes through the unobtrusive but consistent character development. In the early minutes of the film there’s an almost sitcomish feel to the movie, as Akiko tries to keep Masakazu’s editor (Shinichi Tsutsumi) from finding out that Masakazu’s assignment isn’t done; she fails, though, and this ends up enhancing our sympathy for all three characters, who react less dramatically than we might think. All of them end up playing significant roles in the film, and their movement through the episodes, what we learn and how we see them change, makes the story feel like a cohesive whole.

In particular, all the lead characters and most of the minor ones are wholly sympathetic. There’s a pervasive good cheer to this Kamakura, where everybody’s pretty nice to each other, human or not. The Shinigami, the minor death gods (played here by Sakura Andô, unrecognisable from her star turn in 100 Yen Love), are always polite, always bright and smiling, always ready to help humans — if they’re ready to move on from this world the Shinigami accompany them on their final train ride, or if they want to remain on earth as ghosts to help their family the Shinigami will show them how to apply for ghosthood. Either way, the most implacable fact of nature is given the smiling face of an ally. The final resolution of the film is in good part set up by the fact that Akiko in particular is nice to someone that absolutely nobody else has any time for. That’s a fine touch, sealing a film that’s quietly filled with themes about relationships and community, and about how these things can persist after death.

This isn’t a film overly concerned with profundity, but neither is it treacly or simplistic. It deals with death and rebirth and love across time; also with identity and community. Kamakura becomes a place where a human world and a spirit world mingle. After Masakazu takes Akiko through an almost Richard Dadd–like Night Bazaar filled with inhuman spirits, he reflects that “it’s the real Kamakura.” We’re in the position of Akiko, learning from him about this weird world and its rules: the reality previously undreamed-of. But I wonder if the line’s meant to imply the Bazaar is real in the way that it has living and dead, mortal and spirit, all mixing together: the real and the fantastical, the past and the present. Either way, it’s one of many glorious moments that Destiny provides with unexpected generosity.

This isn’t a film overly concerned with profundity, but neither is it treacly or simplistic. It deals with death and rebirth and love across time; also with identity and community. Kamakura becomes a place where a human world and a spirit world mingle. After Masakazu takes Akiko through an almost Richard Dadd–like Night Bazaar filled with inhuman spirits, he reflects that “it’s the real Kamakura.” We’re in the position of Akiko, learning from him about this weird world and its rules: the reality previously undreamed-of. But I wonder if the line’s meant to imply the Bazaar is real in the way that it has living and dead, mortal and spirit, all mixing together: the real and the fantastical, the past and the present. Either way, it’s one of many glorious moments that Destiny provides with unexpected generosity.

After Destiny would come Aragne, but before the 75-minute Aragne was a 21-minute short called “Walking Meat.” Directed by Shinya Sugai (an animator on Napping Princess) from a script by Daishiro Tanimura, it’s a fast and funny animated near-future zombie story. It’s not about a zombie apocalypse, though; rather the opposite. This is a world where human beings have figured out how to hypnotise zombies and get them to walk into a slaughterhouse — where they’re chopped up and turned into a zombie food product. The film follows three young interns, Marin (Maaya Uchida), Masaru (Fukushi Ochiai), and Kaori (Minami Tsuda) as they arrive at the slaughterhouse/factory for training under a bitter old instructor, Hasegawa (Kenjirô Tsuda). Unsurprisingly, things go wrong, and the foursome must fight their way out from under a zombie horde, despite none of them having any use for the others.

“Walking Meat” is fast, funny, and nice to look at. It’s highly kinetic, with lots of well-animated movement, and the pacing suits both the action and comedy beats. The story’s simple but effective, giving each of the characters something to do that suits their archetype, and everybody gets a moment of awesome before the story’s all done. I wouldn’t call it an outright satire, but it gets its pokes in at commercialism and work hierarchies. It’s well-executed and builds to a good final gag. Despite being more than 20 minutes, it flies by. It’s not revolutionary by any stretch, but it’s a damned enjoyable playing-about with anime action tropes and character beats, and overall does just what it wants to do.

“Walking Meat” is fast, funny, and nice to look at. It’s highly kinetic, with lots of well-animated movement, and the pacing suits both the action and comedy beats. The story’s simple but effective, giving each of the characters something to do that suits their archetype, and everybody gets a moment of awesome before the story’s all done. I wouldn’t call it an outright satire, but it gets its pokes in at commercialism and work hierarchies. It’s well-executed and builds to a good final gag. Despite being more than 20 minutes, it flies by. It’s not revolutionary by any stretch, but it’s a damned enjoyable playing-about with anime action tropes and character beats, and overall does just what it wants to do.

Aragne: Sign of Vermillion followed. Directed, written, and animated by Saku Sakamoto, it’s his feature film debut; and very nearly a one-man project. It begins with a prologue, showing us disturbing medical experimentation in World War Two, then skips to the present day for the main story, which follows a student named Rin (Kana Hamazawa, who voiced the lead in Night is Short, Walk On Girl) as she settles in to her new home in a disturbing run-down concrete apartment tower. Eerie things begin to happen: she sees a woman with a bug crawl from her arm, another woman always pushing a black baby carriage, reports emerge that the apartment building’s built on repurposed industrial land, there are curses and a secret circle that keeps the curses at bay, there are murders. And what about the medical experiments? Things build, growing weirder and more disturbing. Always at the core there are bugs, moths, insects linked to the human spirit, preying and metamorphosing.

This may sound very general, and this is because frankly a precise plot description is impossible. The plot here is erratic at best, incorporating a wide range of imagery and ideas without (to my mind) ever really cohering. The movie still might have worked, but I can’t think of a way to watch the film that isn’t sabotaged by the film itself.

Before explaining what I mean by that, let’s establish first that the movie looks excellent. The designs are memorable and eerie, the architecture of the apartment complex cyclopean and desolate yet modernist. Characters sometimes seem to have a glazed expression — the downside of CGI — but resolve into suitable detail for close-ups and important moments. Crucially, they move well, with a strong sense of timing. Individual sequences have a great horror-movie pace, letting atmosphere build before bringing in real terror with devices more complex than jump-scares.

The problem is that while many of the scenes work fine, the film as a whole doesn’t. It’s overall slow, feeling much longer than an hour and a quarter, and I think that’s because nothing seems to follow logically or coherently — there’s a general increase of a sense of threat and of the scale of the threat, but the emotional pitch doesn’t vary much, while the clues Rin uncovers about what’s happening don’t seem to add up. There is a late-film revelation which might explain some of that, but in addition to being unconvincing in its own right, it also doesn’t help much while in the process of watching the movie and trying to make sense of it.

The problem is that while many of the scenes work fine, the film as a whole doesn’t. It’s overall slow, feeling much longer than an hour and a quarter, and I think that’s because nothing seems to follow logically or coherently — there’s a general increase of a sense of threat and of the scale of the threat, but the emotional pitch doesn’t vary much, while the clues Rin uncovers about what’s happening don’t seem to add up. There is a late-film revelation which might explain some of that, but in addition to being unconvincing in its own right, it also doesn’t help much while in the process of watching the movie and trying to make sense of it.

So: the story can’t be enjoyed as a well-plotted puzzle or mystery that becomes clear bit by bit. I woud argue, though, that the puzzle pieces we do get are too numerous and too central to the film for Aragne to be easily enjoyed as a stream of hallucinatory imagery. The nods to reason distract from the trancelike feel that might otherwise develop here. This is a film that seems to be trying to make sense, and to be encouraging the viewer to make sense of it. That may be a feint, but at one viewing I’d say it’s too much a core part of the film for a feint. Rin’s trying to make sense of things, visitng libraries and talking to folklorists and finding out bits of knowledge. I did not feel at the end of the film that this was futile so much as that pieces were missing, and some seemed to be from a different puzzle entirely.

I don’t think it’s possible to follow the film as a character piece, either. Rin’s clearly central, with no other character really given significant screen time or internal life. But she remains oddly nonspecific, a vaguely sympathetic protagonist whose background is unspecified and whose emotions are too general — the movie gives her no reason to feel or express anything but different shades of fear. There is a revelation near the end of the film that has the structural feel of an explanatory key, but which actually explains very little.

It’s hard to isloate a theme that anchors the film, either. “Humans try to silence our fears by communicating with others,” one of Rin’s teachers observes early on. It’s an accurate and resonant line, but Rin doesn’t try to communicate with anyone much, and indeed there’s very little communication going on in this movie. (The teacher doesn’t return that I noticed, and the idea of school soon drops out.) There is an attempt, I think, to use the insect imagery to make a point about the nature of one’s spirit and emotional life. But it’s confused by the many other things going on in the movie, and is hard to isolate when watching or afterward.

There are lots of ideas in Aragne, at least in terms of set-pieces. There are some interesting chase scenes, well-designed horrors, architecture that brings out atmosphere — when, late in the film, Rin finally makes her way to the abandoned medical institution of the prologue, it’s a very strong setting. But nothing builds from scene to scene, and too many scenes end less with shock than confusion. There’s very real talent in this movie. I can understand someone enjoying it for its moments of atmosphere alone. But for me it’s an example of a film that’s much less than the sum of its parts, because the parts actively resist being added together.

There are lots of ideas in Aragne, at least in terms of set-pieces. There are some interesting chase scenes, well-designed horrors, architecture that brings out atmosphere — when, late in the film, Rin finally makes her way to the abandoned medical institution of the prologue, it’s a very strong setting. But nothing builds from scene to scene, and too many scenes end less with shock than confusion. There’s very real talent in this movie. I can understand someone enjoying it for its moments of atmosphere alone. But for me it’s an example of a film that’s much less than the sum of its parts, because the parts actively resist being added together.

After the film, Saku Sakamoto came out for a question-and-answer period (note that what follows is reconstructed from my handwritten notes, and that some of Sakamoto’s Japanese answers were translated into French, my second language). Asked how the project began conceptually, he said that he had worked as an assitant on films made by producer Osamu Fukutani, and specialised in horror. Asked about the release date for the film, he said it comes out in Japan on August 18, but at the moment there are no plans for the rest of the world. Asked about the medical experiments shown in the film, Sakamoto said they were inspired by various things but no specific real history, although they did use elements from the history of experiments on humans conducted by the Japanese during World War Two.

Asked whether he thought CGI was good for animation in general, Sakamoto said he thought it meant one can make more things thanin the past; but there’s a lot that cannot be expressed without drawing with one’s hands. Finding the right mix is perhaps the goal for the future. His producer, Osamu Fukutani, observed that the mix made the film possible for Sakamoto to do alone. They’d had to use more 3D because they had no budget for hand-drawn animation, reserving that for more important scenes.

Asked about the ending, Sakamoto said that the film originally had one storyline, and more elements were added as the film was made. He noted that it’s hard to be sure as a result what in the film is real and what is imagination. He said he preferred to leave that to the individual viewer, as he doesn’t want to define things. Asked about the use of bugs in the film, he noted that there was an old expression in Japan about one’s soul being guided by bugs, and described a belief that bugs serve as guides to transport souls after death. He felt the image added a touch of Japanese horror.

Asked about his next project, Sakamoto said he wasn’t attached to a specific project, but was researching ideas, and wanted to continue in indie animation. Fukutani said he’d like to collaborate more with Sakamoto in future. Asked how he came up with the title, Sakamoto mentioned Greek myth, and seeing an image based off mythology involving a woman’s head on a spider’s body.

Asked about his next project, Sakamoto said he wasn’t attached to a specific project, but was researching ideas, and wanted to continue in indie animation. Fukutani said he’d like to collaborate more with Sakamoto in future. Asked how he came up with the title, Sakamoto mentioned Greek myth, and seeing an image based off mythology involving a woman’s head on a spider’s body.

That ended the questions, and the remaining audience filed out so the staff could clean the theatre. Next I’d return to the Hall to see another, very different, horror film. Looking at the schedule, what came next was up in the air; but if I were lucky, I’d get to go through hell in interesting company.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.