Fantasia 2018, Day 3, Part 2: Boiled Angels: The Trial Of Mike Diana

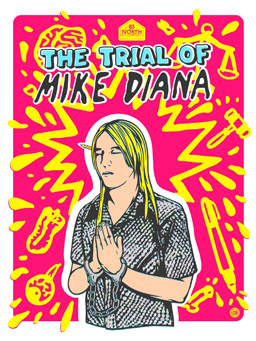

After my first two films last Saturday, I left the large Hall Theatre to see a documentary in the 150-plus-seat De Sève Theatre across the street. The documentary was called Boiled Angels, and it presented the case of zinester and comics creator Mike Diana, whose transgressive work led to him being arrested and put on trial in Florida in the 1990s. I’d followed Diana’s plight at the time through reports in The Comics Journal, and was intrigued to learn more about it now. But if I personally was interested in the film as a look at comics history, I was surprised to find that much of the rest of the crowd was drawn by the chance to see new work by horror director Frank Henenlotter, creator of works like Bad Biology, Frankenhooker, Brain Damage, and Basket Case.

After my first two films last Saturday, I left the large Hall Theatre to see a documentary in the 150-plus-seat De Sève Theatre across the street. The documentary was called Boiled Angels, and it presented the case of zinester and comics creator Mike Diana, whose transgressive work led to him being arrested and put on trial in Florida in the 1990s. I’d followed Diana’s plight at the time through reports in The Comics Journal, and was intrigued to learn more about it now. But if I personally was interested in the film as a look at comics history, I was surprised to find that much of the rest of the crowd was drawn by the chance to see new work by horror director Frank Henenlotter, creator of works like Bad Biology, Frankenhooker, Brain Damage, and Basket Case.

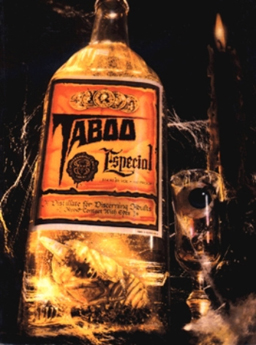

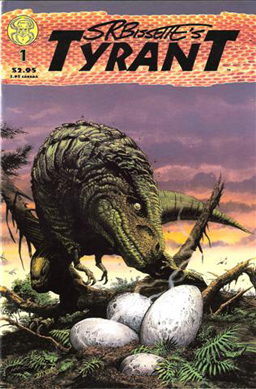

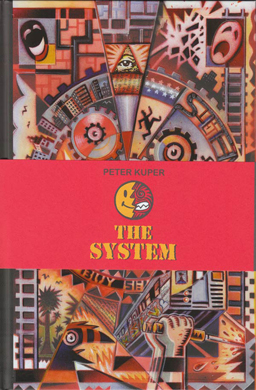

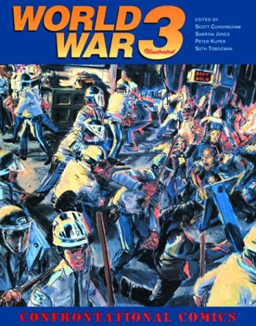

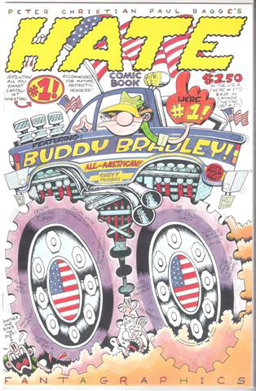

Boiled Angels is his third documentary, and boasts interviews with comics luminaries like Neil Gaiman, Steve Bissette (Taboo, Tyrant, art on Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing run), Peter Kuper (The System, World War 3 Illustrated), and Peter Bagge (Hate). It’s narrated by Jello Biafra, and does a strong job in tracking down and interviewing people who were involved with Diana’s case nearly twenty-five years ago. We see and hear from Diana’s parents, from the prosecutors, from journalists, even from one of the women who protested Diana at the courtroom. They speak to an off-camera interviewer we don’t hear; we also see Diana himself, describing his background and life. Diana’s comics are dramatised by a live reading by the creator, the camera focussing on the panels as Diana reads out the dialogue. Other segments of the film, particularly early on, give background on things like the history of horror comics, underground comics, and early-90s zine culture. And there are clips of talk shows and news shows dealing with Diana’s case.

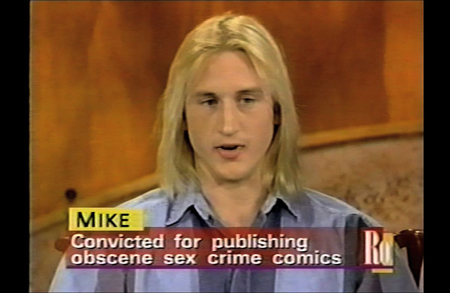

There’s not much debate over what actually happened to Diana. In the early 1990s, when he was in his early and mid 20s, he sold a few hundred copies of his obscure comics zine Boiled Angel through the mail. The content of the zine was brought to the attention of the Florida authorities (although there’s a minor dispute about how). Diana had written and drawn comics filled with horror, rape, mutilation, and various kinds of unpleasantness; seemingly as many kinds of unpleasantness as he could think of. For doing so, he was arrested, tried, and found guilty of obscenity. He was fined and put on probation. Drawing comics would potentially violate his probation and cause him to be thrown in jail. And he was subject to warrantless searches to ensure he was not in fact drawing. In other words: the legal authorities forbade an American artist from making art.

Henenlotter does a solid job of exploring the issues around the case. Since seeing the film I have spoken to one person who wasn’t familiar with what happened to Diana who found the narrative of the trial unclear. But I think that Henenlotter effectively brings in the themes and subtexts that led to Diana’s work and to his arrest. The movie talks about EC comics and the undergrounds, and explores Diana’s youth — particularly his move from upstate New York to small-town Florida, and how he was appalled what he found there. I thought Biafra’s narration was poor — his readings were often over-ironic to my taste — but the filmed interviews were often powerful.

Henenlotter does a solid job of exploring the issues around the case. Since seeing the film I have spoken to one person who wasn’t familiar with what happened to Diana who found the narrative of the trial unclear. But I think that Henenlotter effectively brings in the themes and subtexts that led to Diana’s work and to his arrest. The movie talks about EC comics and the undergrounds, and explores Diana’s youth — particularly his move from upstate New York to small-town Florida, and how he was appalled what he found there. I thought Biafra’s narration was poor — his readings were often over-ironic to my taste — but the filmed interviews were often powerful.

Still, Henenlotter’s honest in depicting Diana’s work. As film, the readings of the comics aren’t especially exciting, but then I don’t think anybody’s yet cracked how to translate the experience of reading comics onto film. Comics play with the page structure to shape timing and the speed the reader moves through the story, so having that control of time and the reading eye taken away by a director is annoying. But for Boiled Angels it’s necessary. We have to know what Diana’s comics are like. Basic honesty requires us to have a sense of the work that led his conviction. Henenlotter had a no-win choice to make — skip the comics or show them — and I think he did make the honorable one, showing the audience the content at issue. (You’ll note little of Diana’s art accompanies this article; I couldn’t find an example appropriate for this web site. Feel free to look for yourself, but note that his work does combine graphic sex and extreme violence and torture.)

Certainly the comics are transgressive. Peter Kuper notes that they were largely amateurish as well; I recall (and it’s mentioned in the film) some discussion among people in comics about how intensely to defend someone whose work was so poor. I’m not sure that the art’s entirely without redeeming aspects. There’s a certain punk graphic sensibility, a thick ink line, a basic sense of visual storytelling (although not a flawless or especially notable one). There’s also an abiding if unsubtle sense of the grotesque. I would say that beyond the omnipresent rape, mutilation, bestiality, violence to children, and whatever else, there’s also a constant sense of what you might call a grimdark world — not only do horrible things happen, they happen to the innocent. Pain’s everywhere.

Certainly the comics are transgressive. Peter Kuper notes that they were largely amateurish as well; I recall (and it’s mentioned in the film) some discussion among people in comics about how intensely to defend someone whose work was so poor. I’m not sure that the art’s entirely without redeeming aspects. There’s a certain punk graphic sensibility, a thick ink line, a basic sense of visual storytelling (although not a flawless or especially notable one). There’s also an abiding if unsubtle sense of the grotesque. I would say that beyond the omnipresent rape, mutilation, bestiality, violence to children, and whatever else, there’s also a constant sense of what you might call a grimdark world — not only do horrible things happen, they happen to the innocent. Pain’s everywhere.

What drove Diana to make the art? The question’s almost beside the point, as his motivation’s irrelevant to the facts of his trial. But he’s a character in the film, and as such it’s good to know what was in his head. His sensibility was shaped by low-budget horror movies, sure, but that alone doesn’t explain the comics. Diana says that he was appalled at the world around him, that the comics are a reflection of the reality of Floridian life and morals. I tend to believe him, but here I think the film does him a disservice in not considering how this particular reaction perhaps made more sense twenty-five years ago.

Let me step back: Henenlotter’s film begins with an over-the-top self-mocking warning sign, noting the sexual and violent content of what follows. Calling it “un-PC,” as the text does, is to my mind misplaced but also seems to point out one of the odd characteristics of the film. What I mean is that in the context of the early 1990s, “politically correct” at least sometimes referred to the use of euphemism to deny reality: the canonical example was using “sanitation engineer” as a replacement for “garbageman” — not to be less gender-specific, but to avoid the use of “garbage.” Move forward to today, and I’d argue that use of “politically correct” has all but vanished (and ‘sanitary engineer’ seems to have become an accepted term in a number of contexts). Nowadays “politically correct” seems mostly used by racists and misogynists to sneer at people displaying a minimal amount of empathy. It’s fair to argue that this was implicit in the 1990s use of the term, but in my experience there’s been a distinct shift in meaning, or at least loss of meaning. The way the phrase is used at the start of the movie is something of a sign that the movie’s adopting a 1990s viewpoint wholesale.

Let me step back: Henenlotter’s film begins with an over-the-top self-mocking warning sign, noting the sexual and violent content of what follows. Calling it “un-PC,” as the text does, is to my mind misplaced but also seems to point out one of the odd characteristics of the film. What I mean is that in the context of the early 1990s, “politically correct” at least sometimes referred to the use of euphemism to deny reality: the canonical example was using “sanitation engineer” as a replacement for “garbageman” — not to be less gender-specific, but to avoid the use of “garbage.” Move forward to today, and I’d argue that use of “politically correct” has all but vanished (and ‘sanitary engineer’ seems to have become an accepted term in a number of contexts). Nowadays “politically correct” seems mostly used by racists and misogynists to sneer at people displaying a minimal amount of empathy. It’s fair to argue that this was implicit in the 1990s use of the term, but in my experience there’s been a distinct shift in meaning, or at least loss of meaning. The way the phrase is used at the start of the movie is something of a sign that the movie’s adopting a 1990s viewpoint wholesale.

And I’d argue that the impact of Diana’s art was very different in the 1990s than it is now. Quite probably Diana’s drive to make the comics, to transgress, had to do with the situation then — before the World Wide Web. This was a time when someone in a given physical place was much more anchored in the culture of that place than they are now. There wasn’t quite the same possibility of escape. It’s not surprising that Diana reacted to the oppressive worldview all around him by creating art that rejected that worldview as violently as possible.

Early in the film, George Romero reflects on the influence of EC Comics, and notes that finding a shop that sold ECs was “like a minor version of where do you get your dope.” Transgressive horror comics were a way out from under the mainstream culture of the time. I’d argue a lot of subcultures of the time had the same effect, including the punk subculture and the zine subculture. EC Comics ran into problems with the law, determined to enforce the authorities’ idea of approved culture. Henenlotter’s implicit point is that what happened to Diana was much the same thing, which I would say is fair. But I’d also say that things are very different now. Baggish actually makes this point, observing that the obscenity statue under which he prosecuted Diana means that what was obscene in the 1990s is not necessarily obscene today. Of course people are still stuck in terrible situations around the world. But it’s much easier to find an imaginative escape, and to connect with an alternate non-geographic community of like-minded people. I feel it would have helped the movie to discuss how isolated Diana must have been at that time.

Certainly, while “free speech” controversies of various kinds are much spoken of today, it’s not clear how direct the parallels are with Diana’s case. His story is a clear-cut case of the government going after an artist. Neil Gaiman, as an outsider to the US much enamored of the First Amendment, gives the most moving expression of the importance of the case: the government told an artist not to make art it disapproved of. Henenlotter avoids trying to situate Diana’s art in the context of comics or fine art, presumably judging that such things are beside the point. He’s likely correct. Seeing a young Baggish declare that obscenity is a local matter, and that what is acceptable in “the bathhouses of San Francisco and the crackhouses of New York City” is not necessarily acceptable in Florida is eye-opening. In this sense Diana’s case resonates; a conservative DA went after him with rhetoric that was clearly homophobic and almost certainly playing to racial prejudice as well (Diana’s jury was all-white, and none under the age of 35).

Certainly, while “free speech” controversies of various kinds are much spoken of today, it’s not clear how direct the parallels are with Diana’s case. His story is a clear-cut case of the government going after an artist. Neil Gaiman, as an outsider to the US much enamored of the First Amendment, gives the most moving expression of the importance of the case: the government told an artist not to make art it disapproved of. Henenlotter avoids trying to situate Diana’s art in the context of comics or fine art, presumably judging that such things are beside the point. He’s likely correct. Seeing a young Baggish declare that obscenity is a local matter, and that what is acceptable in “the bathhouses of San Francisco and the crackhouses of New York City” is not necessarily acceptable in Florida is eye-opening. In this sense Diana’s case resonates; a conservative DA went after him with rhetoric that was clearly homophobic and almost certainly playing to racial prejudice as well (Diana’s jury was all-white, and none under the age of 35).

One of the journalists who covered the case in the 1990s reflects on what he saw, on protesters crying when he began to film, and notes that this isn’t too surprising: “when the camera comes on, the drama begins.” Henenlotter’s success as a documentarian is the sense that he’s not creating drama. He’s letting people discuss their actions and opinions honestly. I admit I find the case clear. But it’s fascinating seeing people who think differently, explaining their attitudes and motivations. If you’re interested in comics culture, and arguably in 1990s culture in general, this is a valuable piece of work.

After the film, Festival director Mitch Davis hosted a question-and-answer period with Mike Diana and the film’s creators, beginning by asking how director Frank Henenlotter became friends with Diana. The energetic and voluble Henenlotter recalled meeting him at a screening of Henenlotter’s film Bad Blood in 2010, which led to inviting him over and talking about film. That led to weekly informal movie nights in which Henenlotter introduced Diana to various films. After about six months Henenlotter asked why he came to New York, and a shy Diana answered that he’d come up after the trial. Henenlotter read up on the whole story through Google, thinking Diana’s story didn’t make sense, and found that in fact the whole situation didn’t make sense. Which led him to ask Diana if he could make a documentary about it.

Davis asked Diana what it was like to see all the faces of his persecutors again, and Diana said it was interesting and brought back memories. He said it was good to tell the story the way he wanted, and to have his costs finally paid off (which was done as part of the production; he’s now officially a free man in Florida). Henenlotter noted that a scene in which Diana’s spooked by a police car passing wasn’t play acting, that Diana really was jittery. Producer Anthony Sneed remembered Diana running away when they were shooting around Diana’s old house and the current owner threatened to call the cops. Henenlotter noted this was occasionally an issue in that the trick to shooting somewhere without a permit is to look like you have a permit and belong there. So whenever there was any police presence in a shooting location, Diana would simply wander away. Henenlotter recalled dealing with the police while shooting his earlier documentary Chasing Banksy, and how he’s not intimidated by cops as two of his brothers are policemen.

Davis asked Diana what it was like to see all the faces of his persecutors again, and Diana said it was interesting and brought back memories. He said it was good to tell the story the way he wanted, and to have his costs finally paid off (which was done as part of the production; he’s now officially a free man in Florida). Henenlotter noted that a scene in which Diana’s spooked by a police car passing wasn’t play acting, that Diana really was jittery. Producer Anthony Sneed remembered Diana running away when they were shooting around Diana’s old house and the current owner threatened to call the cops. Henenlotter noted this was occasionally an issue in that the trick to shooting somewhere without a permit is to look like you have a permit and belong there. So whenever there was any police presence in a shooting location, Diana would simply wander away. Henenlotter recalled dealing with the police while shooting his earlier documentary Chasing Banksy, and how he’s not intimidated by cops as two of his brothers are policemen.

Asked if the transgressive has become dangerous again, Diana said it was important to keep pushing and expose what one sees. Sneed said that if people are afraid of being offended, it is therefore a good time to offend. Asked about bringing in Biafra as a narrator, Henenlotter said that he didn’t know him, but talked with him on the phone and arranged the performance; he was inspired to approach Biafra because Biafra had been prosecuted for obscenity himself in the mid-80s. Asked about the thorough research, and finding people involved with the case, Henenlotter noted it was Sneed’s work, finding people like the former newscaster who now works in real estate. Sneed said he got a kick out of tracking people down, and observed that the real trick was finding Baggish; he’d persevered because the filmmakers felt they had to have him in the movie.

Henenlotter said Baggish was the anchor. It was no big deal to get people to praise Diana, but he had to know how the prosecution happened and Baggish was the only one who could tell them that. He found that Baggish was a gentleman; when Henenlotter told him that he believed in Diana, he acknowledged and accepted that. He was also well-prepared for the interview when they sat down for it. Sneed recalled texting him with a very carefully-phrased message, then going to email after getting a positive response. Sneed suspected Baggish felt his interview would look good to people who were on his side politically. Henenlotter said he really believed that Baggish felt Diana’s material was terrible. Baggish asked him if he’d show the art in the documentary, and when Henenlotter said yes, it would be shown uncensored, Baggish said “good, good.”

Asked if anyone refused to be in the film, Sneed said they’d hoped to get Luke (Luther Campbell) from 2 Live Crew, who refused in part due to his wife’s political interests. The judge in the case was still sitting, and so declined an interview. The biggest issue was probably not getting the police officers who bought Diana’s book for the purpose of establishing that he’d sold obscene material; Henenlotter’s cop brothers believed the police actions constituted entrapment, and the filmmakers had hoped to talk to them about that, and about how exactly Diana came to their attention. Henenlotter said he really would have liked to get the psychologist who testified for the prosecution; he said he would have broken one of his own rules and debated him on-camera.

Asked if anyone refused to be in the film, Sneed said they’d hoped to get Luke (Luther Campbell) from 2 Live Crew, who refused in part due to his wife’s political interests. The judge in the case was still sitting, and so declined an interview. The biggest issue was probably not getting the police officers who bought Diana’s book for the purpose of establishing that he’d sold obscene material; Henenlotter’s cop brothers believed the police actions constituted entrapment, and the filmmakers had hoped to talk to them about that, and about how exactly Diana came to their attention. Henenlotter said he really would have liked to get the psychologist who testified for the prosecution; he said he would have broken one of his own rules and debated him on-camera.

Asked about the soundtrack, Scooter McCrae, who did the music for the film, said that he gave Henenlotter a lot of music — some composed for the film and some not — and told him to use it as he wished. The film’s like a collage, and the music follows from that, incorporating his score and some punk songs. McCrae said he thought Henenlotter had done a good job. Henenlotter said the trick was juxtaposing one piece of music with another.

An audience member asked Diana how he thought his art would be different if he hadn’t moved to Florida. Diana said it was hard to say; he’d been a fan of the weird from his youth, but Florida was a strong influence: the heat, the religion, police harassment, adults who disapproved of kids and wanted to tell you what to do. He felt he was reflecting the community around him. Henenlotter was asked if Baggish reversed himself at all; the director said no. Baggish was still a lawyer, and probably wouldn’t admit if it he had changed his mind, but Henenlotter didn’t think he had. Henenlotter observed that he did want to find the arresting officer because he’d heard at second hand that he now felt bad, and hadn’t expected everything he’d brought down on Diana.

Sneed observed there where no 180-degree turns, the closest being the protester who offered a partial apology. Henenlotter said he thought she agreed to do the film because she thought she looked bad; she’s not the same person now. He told stories about filming at her home, from seeing a Glock on the counter to being given excellent food. Henenlotter said he’d told her that Diana’s art would be in the film, and she said she trusted him more for his bringing it up. She was thrown, though, by his mention that Diana was a good friend. He said she legitimately believed she was protesting against violence done to children, but was moved by hearing what had happened to Diana.

Sneed observed there where no 180-degree turns, the closest being the protester who offered a partial apology. Henenlotter said he thought she agreed to do the film because she thought she looked bad; she’s not the same person now. He told stories about filming at her home, from seeing a Glock on the counter to being given excellent food. Henenlotter said he’d told her that Diana’s art would be in the film, and she said she trusted him more for his bringing it up. She was thrown, though, by his mention that Diana was a good friend. He said she legitimately believed she was protesting against violence done to children, but was moved by hearing what had happened to Diana.

The last question from the audience was whether Henenlotter’s commitment to free speech included hate speech. Henenlotter said that while he wasn’t happy about it he saw no way around it. Freedom of speech, he observed, means accepting it all. You can protest it, but you can’t stop it. He said he himself had stopped watching the news because of all the hate speech emanating from the White House. In response to that, Sneed observed that in the United States, “we’re turning into Florida, but we’re not turning into Floridians.” Which was an interesting thought to end on.

Find the rest of my coverage of Fantasia 2018 here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.