Fantasia 2018, Days 1 and 2: Five Fingers of Death

Fantasy’s described by fantasy: consider John Crowley’s Little, Big, a novel about a faerieland where the further in you go the bigger the land becomes. A powerful image, it echoes the way fascinations gain in depth and scope the more you explore them. How familiar experiences can become strange the more you dig deeper into them, birthing mystery, growing weird. Art and story perhaps most of all. So I am about to begin my coverage of the Fantasia International Film Festival for the fifth year here at Black Gate, and I feel I have less of an idea of what I will see than ever. It is a place, a time, a state of mind, where anything can be seen; it is one of those notorious worlds whose only boundaries are that of imagination. And so the more you explore the more you learn how much more there is to explore.

Fantasy’s described by fantasy: consider John Crowley’s Little, Big, a novel about a faerieland where the further in you go the bigger the land becomes. A powerful image, it echoes the way fascinations gain in depth and scope the more you explore them. How familiar experiences can become strange the more you dig deeper into them, birthing mystery, growing weird. Art and story perhaps most of all. So I am about to begin my coverage of the Fantasia International Film Festival for the fifth year here at Black Gate, and I feel I have less of an idea of what I will see than ever. It is a place, a time, a state of mind, where anything can be seen; it is one of those notorious worlds whose only boundaries are that of imagination. And so the more you explore the more you learn how much more there is to explore.

This will be the twenty-second edition of the festival, North America’s largest genre film festival, featuring over 130 feature films from around the world. Last year more than 100,000 spectators saw a film at Fantasia, which is impressive in a time of declining theatrical attendance on this continent. But what’s most impressive is the range of offerings at Fantasia. Action-adventure films, experimental and underground films, rediscovered classic films — these things are only the beginning. I argued after last year’s festival that this is a new golden age of science fiction and fantasy film; spend time going through this year’s festival listings and you can see why. Modern genre film is in a complex dialogue with itself across languages and film industries, across years and filmmaking traditions. It is fluid, unpredictable, and international.

I write these posts in a diary format because I think that the experience of attending the festival is worth recording. Over the course of three weeks you see the same people in the media line, you talk with them, you get to know them. And then you see them again the next year. More than that, these are people you talk about films with, agreeing, disagreeing, asking questions, sharing information. I have a number of friends I only see at Fantasia. It’s a community that grows over twenty-one days or so, a little like a science-fiction convention — there’s even a bar where a lot of the festival community hangs out — but instead of (mainly) discussing works of art, we experience the art and then talk about it informally as opposed to attending a panel.

The festival began a little strangely for me, as I saw a film in the screening room on opening day (Thursday, June 12), watched a press screening of another film the next day, then saw another film in the screening room and went off to write up my notes. Then returned at 10:15 on the Friday night to see my first theatrical presentation before a general audience of the 2018 festival. I’ll be writing about those first three films later, but for the moment I want to note that watching movies in the screening room by myself, and even seeing a film with only other media members in a half-full theatre, was very different than attending a showing with a full audience. Waiting in the media line for the first time this year I met new people and reconnected with old friends, then got to see a movie while embedded in a loud and mostly appreciative crowd. (Which happened to include another old friend, not affiliated with the festival. Such is the unexpected serendipity of Fantasia.)

The festival began a little strangely for me, as I saw a film in the screening room on opening day (Thursday, June 12), watched a press screening of another film the next day, then saw another film in the screening room and went off to write up my notes. Then returned at 10:15 on the Friday night to see my first theatrical presentation before a general audience of the 2018 festival. I’ll be writing about those first three films later, but for the moment I want to note that watching movies in the screening room by myself, and even seeing a film with only other media members in a half-full theatre, was very different than attending a showing with a full audience. Waiting in the media line for the first time this year I met new people and reconnected with old friends, then got to see a movie while embedded in a loud and mostly appreciative crowd. (Which happened to include another old friend, not affiliated with the festival. Such is the unexpected serendipity of Fantasia.)

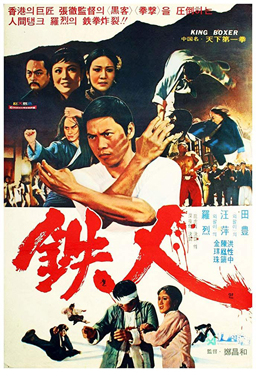

For the past two years I ended Fantasia by seeing a restored classic film of surpassing strangeness: On the Silvery Globe in 2016, Suspiria last year. 2018 began in something of the way those years ended, with a past masterpiece. But of a very different kind. 1972’s Five Fingers of Death (Tian xia di yi quan), also known as King Boxer, was one of the movies that touched off the martial-arts movie craze in North America. Shown at Fantasia in a restored 35mm print, it was introduced by King Wei-Chu, one of the festival’s two Directors of Asian Programming. He told us that the film (titled King Boxer, literally The World’s Best Fighter) was made in Hong Kong in 1972, and released in 1973 in North America; shot after Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon, it made it to American theatres first.

Directed by Chang-hwa Jeong and written by Yang Chiang, the movie’s a solid kung fu story. An old teacher (Wen Chung Ku) sends his prize pupil Chih-Hao (Lieh Lo) to study under a superior teacher, Sun Hsien-Pei (Mien Fang). Only under Sun can Chih-Hao become great enough to defeat a local martial-arts tyrant (Feng Tien) in an upcoming major competition. But said tyrant has brought in a trio of Japanese masters to eliminate all competitors. Will Chih-Hao triumph thanks to his mastery of Hsien-Pei’s powerful technique of the Iron Palm?

The version of the film we saw was subtitled; the English dub apparently uses a different translation, in which the Iron Palm is rendered as the Iron Fist. By either name, the use of the technique’s accompanied by a simple but effective visual effect: a coloured light shines on the martial artist’s hand tensing for battle as it (presumably) becomes like unto a thing of iron. At the same time, a very familiar musical sting plays, later to be used in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. The point is that Five Fingers of Death is an influential movie, one that’s had very direct effects on American popular culture.

The version of the film we saw was subtitled; the English dub apparently uses a different translation, in which the Iron Palm is rendered as the Iron Fist. By either name, the use of the technique’s accompanied by a simple but effective visual effect: a coloured light shines on the martial artist’s hand tensing for battle as it (presumably) becomes like unto a thing of iron. At the same time, a very familiar musical sting plays, later to be used in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. The point is that Five Fingers of Death is an influential movie, one that’s had very direct effects on American popular culture.

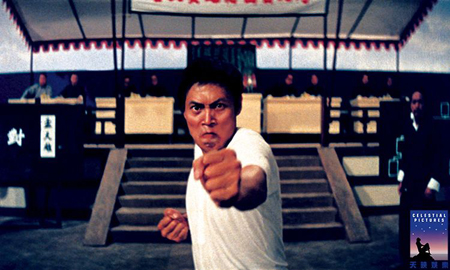

As a kung fu film, it’s perfectly fine. There are a variety of fight scenes, each with its own tone, most with their own style. You see martial artists fighting one-on-one and one-on-many, sparring in training and struggling in grim duels to the death. The editing’s fairly frantic, but the camera moves nicely to follow the running and jumping. And there is jumping, with lots of off-camera springboards or trampolines giving fights a third dimension. The Shaw Brothers Studio had been making these films for years. It happened to be this one that broke through in the United States. So far as I can see from my limited knowledge, it’s a perfectly solid example of where kung fu movies were in the early 1970s. But limited as my knowledge of early kung fu cinema is, American audiences in 1973 would have had much less.

It’s impossible not to try to imagine how this movie must have affected audiences forty-five years ago. Leave aside the non-white cast and the Chinese setting. On a basic level, where could an American audience have seen anything like this? Where would they have seen fight scenes like these? Where, in that year, would they have seen a movie constructed so completely and effectively around fight scenes?

It’s impossible not to try to imagine how this movie must have affected audiences forty-five years ago. Leave aside the non-white cast and the Chinese setting. On a basic level, where could an American audience have seen anything like this? Where would they have seen fight scenes like these? Where, in that year, would they have seen a movie constructed so completely and effectively around fight scenes?

The conventions and techniques of the kung fu movie would have been unfamiliar, but probably easily assimilated. The idea of revenge as a motivator, of the master as a surrogate father-figure, these things would not have been even slightly strange. The idea of martial-arts schools in conflict maybe a bit more so, but comprehensible. Training montages, dramatic music stings, camera zooms — there would have been an obviousness to these techniques, then as now, but I would think also then as now there’d be a palpable energy. Conventions become conventions because they work.

The plot might have been difficult to grasp as a whole. It meanders, and introduces a large number of characters whose paths cross in increasingly complex ways. This strikes me as something Chinese movies (and Asian movies generally) are much more comfortable with than American genre pictures are (or at least were — certainly something like Infinity War doesn’t shy away from loading on characters and subplots). But Five Fingers of Death might have seemed a bit elliptical to Americans in 1973. As it is, it feels a bit messy to me, though it does build well to the big kung-fu tournament and then a brutal fight afterward.

The acting’s decent enough for a genre picture. The old martial-arts teacher played by Wen Chung Ku had a moment I thought was genuinely affecting, when he decides he needs to send his prize pupil to a better teacher because he’s too limited and grown too old to give him the training he needs. Otherwise, the acting serves the story, which is to say it’s not notably deep. I’m not sure how charismatic the cast is as a whole; Chi Chu Chin’s wandering martial-artist Chen Lang is probably the most striking, while Hsiung Chao as the Japanese leader Okada makes a memorable heel. Beyond that, the cast’s relatively straightforward, their performances direct and not too mannered, in keeping with the level of reality overall. It’s not that this is a realistic film, but compared to the stylised action films of the present, you notice a certain level of grit; the way the good martial-arts master Sun Hien-Pei is missing a lower tooth, for example.

The acting’s decent enough for a genre picture. The old martial-arts teacher played by Wen Chung Ku had a moment I thought was genuinely affecting, when he decides he needs to send his prize pupil to a better teacher because he’s too limited and grown too old to give him the training he needs. Otherwise, the acting serves the story, which is to say it’s not notably deep. I’m not sure how charismatic the cast is as a whole; Chi Chu Chin’s wandering martial-artist Chen Lang is probably the most striking, while Hsiung Chao as the Japanese leader Okada makes a memorable heel. Beyond that, the cast’s relatively straightforward, their performances direct and not too mannered, in keeping with the level of reality overall. It’s not that this is a realistic film, but compared to the stylised action films of the present, you notice a certain level of grit; the way the good martial-arts master Sun Hien-Pei is missing a lower tooth, for example.

The overall production value’s reasonably high — outdoor scenes are generally shot outdoors, for example. Nominally a period film, there’s minimal attention paid to establishing a specific sense of an era; there are no cars or guns, but there are cigarettes and electric lights, and that’s about as far as it goes. There’s a sense of timelessness to the film, a kind of archetypal Shaw Brothersness.

I do wonder how the translation and dubbing affected the film and perceptions of the genre. The subtitles we saw were mostly solid, though at one point introducing a chronology error (after a fight, the dialogue indicates a jump forward in time of one year, then other dialogue suggests the fight only happened a few days before). Looking around the web, the dubbing seems to have had more issues, although I suppose it is true that ‘Iron Fist’ sounds more dramatic than ‘Iron Palm.’

I said up above to set aside for a moment how North American genre audiences would have dealt with a Chinese cast in a Chinese setting, but of course that can’t really be set aside at all. There must have been a strangeness to much of the American audience that can’t be recaptured now. Although there’s nothing especially strange in this particular example of the kung fu film, for white audiences in 1973, when distances were greater and the other side of the world farther away, this must have seemed exotic. Perhaps the greatest testament to the film is just that whatever barriers of conscious or unconscious racism existed, this film overcame them — not only to succeed for itself but to kick off a craze for other things like itself.

I said up above to set aside for a moment how North American genre audiences would have dealt with a Chinese cast in a Chinese setting, but of course that can’t really be set aside at all. There must have been a strangeness to much of the American audience that can’t be recaptured now. Although there’s nothing especially strange in this particular example of the kung fu film, for white audiences in 1973, when distances were greater and the other side of the world farther away, this must have seemed exotic. Perhaps the greatest testament to the film is just that whatever barriers of conscious or unconscious racism existed, this film overcame them — not only to succeed for itself but to kick off a craze for other things like itself.

How much that success has to do with conditions as they were forty-five years ago is perhaps the question. We can’t go back to 1973, and in most cases wouldn’t want to. But it’s an interesting exercise to watch a good solid kung fu movie and try to imagine how somebody completely unused to this sort of filmmaking would have reacted. It’s a good start, too, to a festival of genre films, each speaking to each from around the world. Five Fingers of Death was only the beginning for this year’s Fantasia. Almost three more weeks of films wait beyond.

Other coverage of Fantasia 2018 so far includes:

Reviews of the high-fantasy anime Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms and the Chinese kung fu film Unity of Heroes

A review of Boiled Angels, a documentary about comics artist Mike Diana being put on trial for obscenity

More to come!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

“People you only ever see at Fantasia”? I imagine you might count that as a blessing.

Where are the other updates — or have you been busy with your scholarly dissection of “Violence Voyager”?

Oh, “Violence Voyager” will get its due in the fullness of time (I see where one expert review site has it ranked ‘Weirdest,’ which is surely fair). My current plan is to start up the reviews again on Saturday.

You know, it’s almost surprising, but I’ve yet to run into anyone truly annoying at Fantasia. Well, more than once, anyway. But I’m really happy I got to spend time watching and discussing movies with you, Thomas, Dave, Agustin … it’s been a blast.

I must admit that I’ve often gone to Fantasia but stayed in a bubble most of the time. It was a blast having other film-minded people to talk to and the fact that everybody had a different take (or saw something I completely missed) was refreshing. I hope we get to this next year!