A Perfect Dream of Summer: The Mad Scientists’ Club

|

|

In 1970, when I was ten, my city (Bell Gardens, California) built a new state-of-the-art library — right across the street from my house. (It was then that I knew that I was the favorite of the gods. The vicissitudes of life have since led me to revise that reckless assumption, but then I no longer live across the street from a library.) Every time I walked through the building’s doors (five or six times a day, probably), I sent up a silent thanks to Richard M. Nixon, whose name was prominently displayed on the dedication plaque by the entrance, even though he really had nothing to do with the project. (He had other things on his mind in those days — boy, did he.)

I practically lived in that library, and I knew every shelf of the large children’s section intimately; I could have drawn a quite accurate map of the layout from memory, with large arrows pointing to the location of my favorite books, many of which I checked out repeatedly and read over and over again. I retain fond memories of those stories, though nothing in the world would persuade me to reread most of them.

This is because few things in life are more hazardous than returning to a beloved children’s book after the passage of many years. It’s doubly dangerous if the work in question is one that’s “just” a children’s book and not one of those — like Alice in Wonderland or Peter Pan or The Wind in the Willows or the Little House books — that depth and brilliance and long endurance have accorded the status of literature.

There are exceptions, though, children’s books that might be less ambitious than the aforementioned classics but which can still engage an adult reader in search of something more than mere nostalgia. Exceptions like The Mad Scientists’ Club.

[Click the images for mad-scientist-sized versions.]

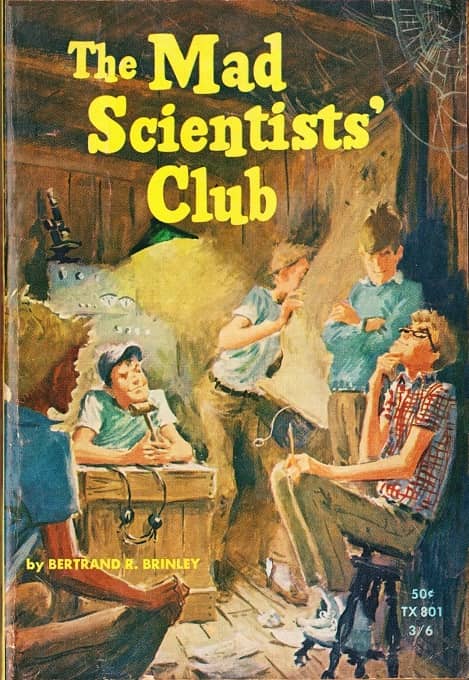

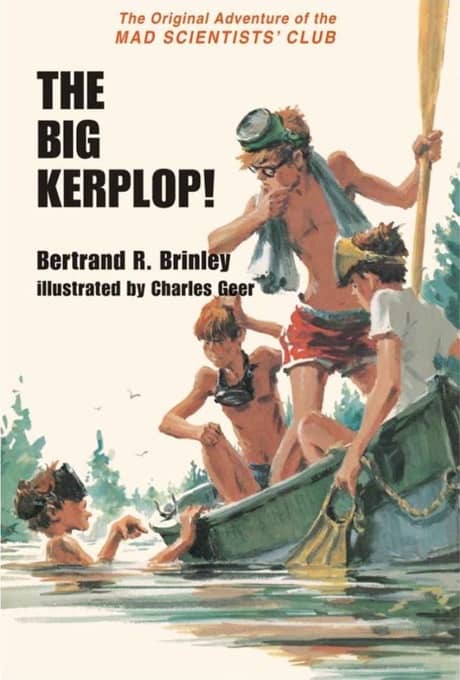

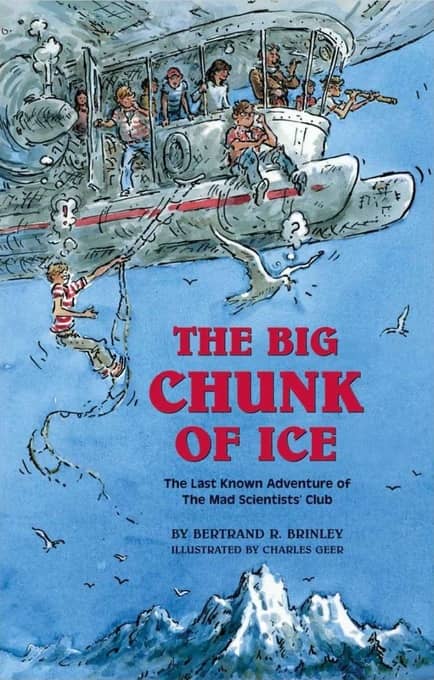

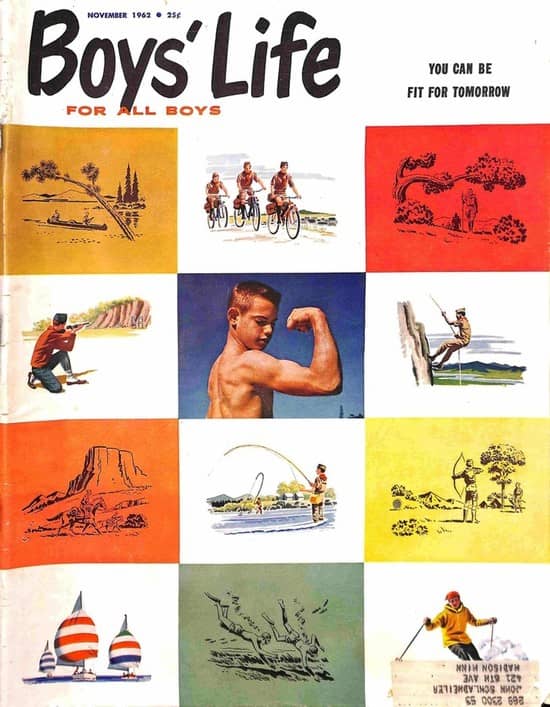

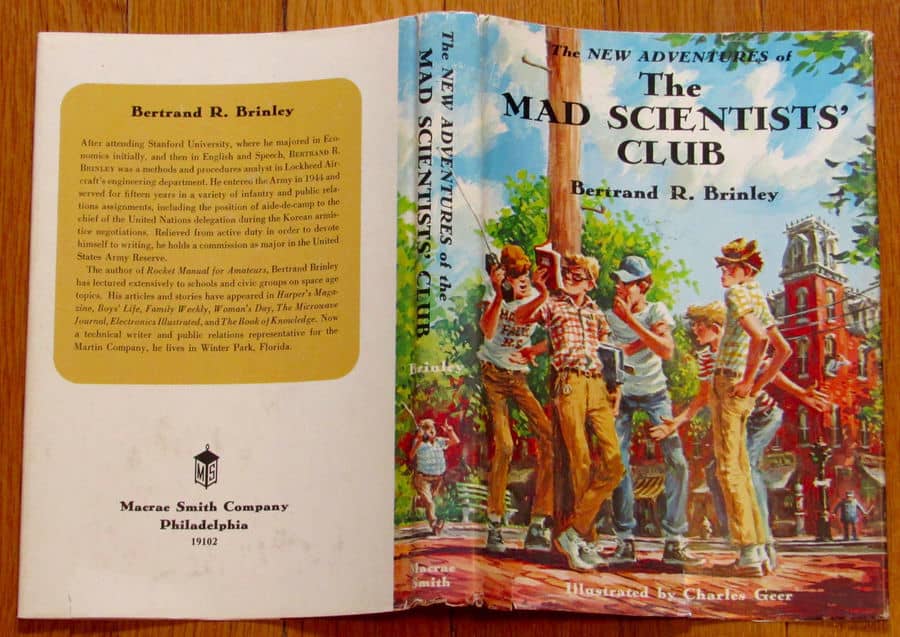

Bell Gardens Library

The Mad Scientist’s Club of the small Midwestern town of Mammoth Falls was the creation of Bertrand R. Brinley (1917-1994), whose career was split between military service (he spent fifteen years in the Army and held a rank of major in the reserves) and writing and public relations work for various aerospace companies. His mad scientists first appeared in 1961 in the pages of Boy’s Life, the official magazine of the Boy Scouts of America, and there were eventually twelve stories featuring the club, the last of which appeared in 1968. They were gathered in two volumes, 1965’s The Mad Scientists’ Club, and 1968’s The New Adventures of the Mad Scientists’ Club. Brinley also wrote two novels in the saga, The Big Kerplop, which was published in 1974, and The Big Chunk of Ice, which was still in manuscript at the time of its author’s death and which didn’t see publication until 2005.

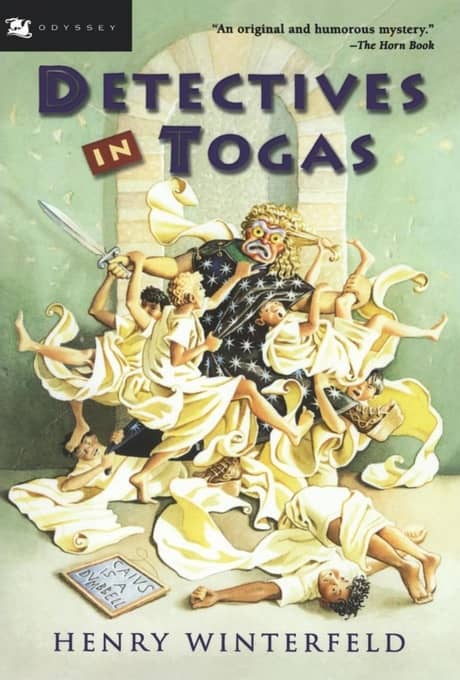

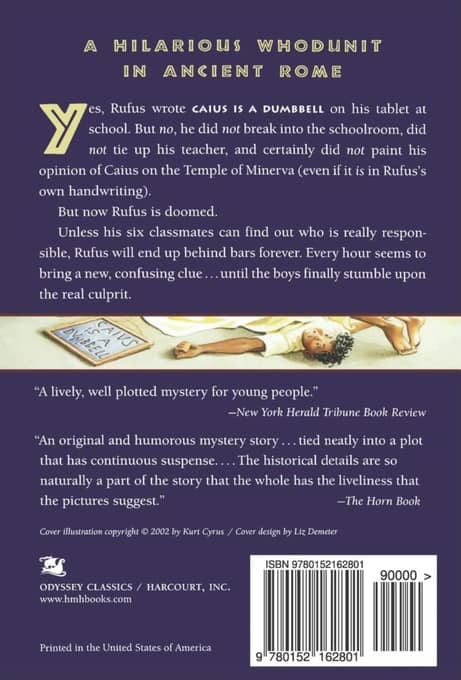

The Bell Gardens library had both of the story collections (I didn’t find out about the novels until decades later), and they were hands-down my two favorite books. I doubt if any other kid in town ever got a look at them, as I kept them more or less constantly checked out. (Their only close competitor was Henry Winterfeld’s Detectives in Togas, a lively story about schoolboys in ancient Rome who team up to solve a baffling mystery. It actually has some strong affinities with the mad scientist tales, and still holds up quite well.)

|

|

The Mad Scientist’s Club has seven members, all boys and all seemingly between thirteen and sixteen years old. Levelheaded Jeff Crocker is the club president (the group meets in his father’s barn) and the blond, bespectacled Henry Mulligan is vice-president and the club’s resident genius and “idea man.” Comic relief is provided by the Laurel and Hardyish pair of overweight Freddy Muldoon and his sidekick, the small and nimble Dinky Poore. The rest of the roster is filled out by Homer Snodgrass, Mortimer Dalrymple (noted for his unflappability, and with a name like that he’d have to be), and Charlie, who narrates the stories. (Charlie didn’t acquire a last name until the final tale in the series, The Big Chunk of Ice. It turned out to be Finkledinck, arguably one Brinley’s few missteps.)

As in many children’s books, most of the stories follow a familiar pattern. In this case, the boys come up with an interesting “research project” and/or see an opportunity to shake their sleepy town up a bit, which they proceed to do with an ingenious application of creative science and practical engineering… which winds up getting them in a fix that they must extricate themselves from with even more creative science and practical engineering.

|

|

Likewise, the boys themselves are “types,” which is common in children’s books of this vintage, which generally didn’t aim for psychological realism or emotional depth. The boys are fun-loving but not malicious; they enjoy bamboozling pompous Mayor Scragg and Billy Dahr, the slow-witted town constable, but their schemes frequently wind up benefiting the community, and the only thing that gets hurt is the pride of a few folks who need to have a little air let out them anyway.

Usually the mad scientists’ projects begin as inventive and elaborate practical jokes, as when they use electromagnets and hidden microphones to transform an abandoned mansion into a genuine haunted house, all in order to scare the beejeebers out of Freddy’s obnoxious cousin Harmon and his gang (“The Voice in the Chimney”), but sometimes the club’s activities have a more serious purpose. The scientists’ resourcefulness saves a life in “Night Rescue,” where they locate a downed Air Force pilot, and in “Big Chief Rainmaker,” the boys use homemade rockets packed with silver iodide crystals to end a drought that’s plaguing the area’s farmers.

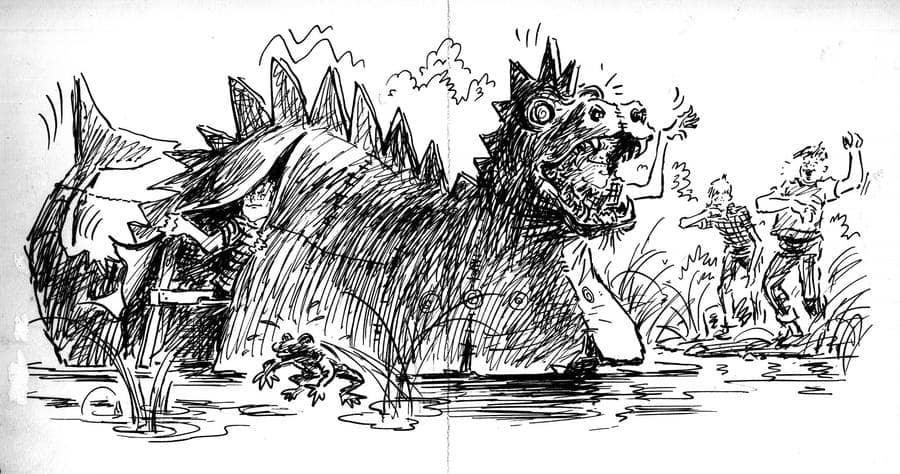

Some stories manage to blend practical jokes with beneficial results, as in “The Strange Sea Monster of Strawberry Lake,” which begins as a prank and ends up helping the town. It was the first Mad Scientist’s Club story, and it’s one of the best.

The Strange Sea Monster of Strawberry Lake

The trouble begins when Dinky Poore has to come up with an excuse for getting home late for supper. He spins an elaborate yarn about “running around the lake trying to get a close look at a huge, snakelike thing he’d seen in the water, and the first thing he knew he was too far from home to get back in time.” His folks don’t necessarily believe this fib, but his sisters are more credulous, and soon they’ve spread Dinky’s fiction all over town, and that’s when the fun really begins.

Henry suggests that it would be relatively simple to build a sea monster, and so it proves. Working in a secluded area near the lake, the mad scientists erect a framework of light lumber “in the shape of a big land lizard” over Jeff Crocker’s canoe. They cover the framework with chicken wire, and when canvas is tightly stretched over that and decorated with paint and tin can lids, (and red-lensed flashlights are installed for the beast’s eyes) the result is all the boys could hope for: “We soon had a loathsome-looking creature guaranteed to scare the life out of anyone a hundred yards away from it.”

With four of the boys hunkered down in their monster to paddle, the creature makes its debut on a Saturday at dusk, “when the lake cabins and beachfront were crowded with weekend visitors.” The club’s creation causes a sensation, and after a few more appearances, nobody in Mammoth falls can talk about anything else. There are newspaper stories and offers of rewards for photos, and the town’s hotel rooms and beachfront cabins fill up with reporters and sightseers from all over the state. The whole thing is a bonanza for the local economy, but there is one drawback:

Pretty soon we realized that we had a tiger by the tail. Business was so good, and people in town were so happy, that we didn’t dare stop taking the monster out, even though it was wearing us down.

Before long the mad scientists have something more serious to worry about — a pair of hunters who make camp on the beach, hoping to get a shot at the monster with an elephant gun. The ever-resourceful Henry has a quick solution to this dilemma: an outboard motor (a very quiet one) attached to the canoe and outfitted so that it can be controlled by radio. Also, since “Freddy could make a bellow like a bull moose on a rampage, because his voice was beginning to change,” the boys place a loudspeaker in the belly of their creature so it can give an occasional roar. (Radio and walkie-talkies are the tools most used by the Mad Scientist’s Club. Today it would be cell phones, and it wouldn’t be nearly as much fun.)

Henry Mulligan thinking

After the first appearance of the new souped-up (and bullet proof — the hunters take their shots, to no effect) sea monster, the town — and not just the town – goes wild:

The next day every newspaper in the country must have carried the story. They quoted eyewitnesses who swore that the monster was mad about something, because it was swimming a lot faster and making a frightening noise. A scientist in New York speculated that it might be the mating season for the beast, and suggested the possibility that there might actually be two of them. Within three days there must have been a hundred and fifty reporters in Mammoth Falls from newspapers, magazines, and radio and television stations. Newsreel camera crews were lined up along the beach, and several of them had large searchlights ready to sweep across the lake at dusk, when the monster usually appeared.

Clearly, the situation is getting out of hand, and when their arch-enemy Harmon Muldoon (who was expelled from the club for giving away club secrets and for “conduct unbecoming a scientist”) starts hinting that he knows what’s really going on and is ready to spill the beans to the media, the boys decide to wrap things up in a decisive and spectacular fashion.

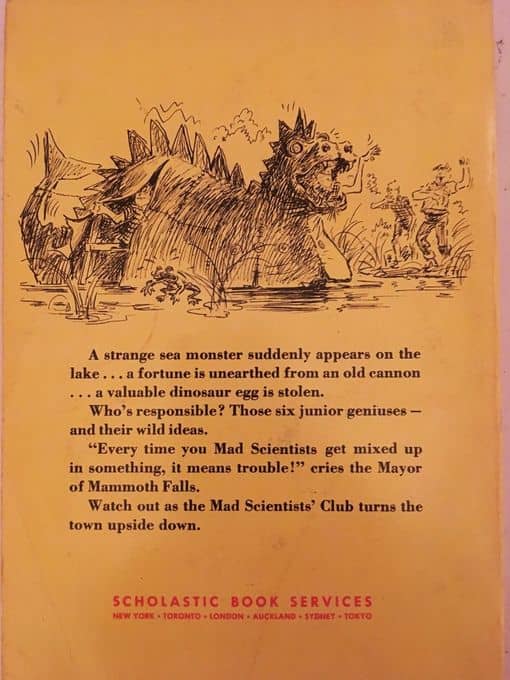

The New Adventures of The Mad Scientists’ Club

Late at night, they strip their equipment off of the creature, mount it on a raft, and tow it out to a spot where it will be visible from the beachfront when the sun rises. Once the people on the shore have noticed the monster’s presence, Henry pushes a button, activating a “diabolical device” the boys have installed, causing their masterpiece to go up in flames.

When the smoke had cleared away there was nothing left on the lake but a dirty smear of oil and a few pieces of black debris — and that was the last that anyone ever saw of the strange sea monster of Strawberry Lake.

As this initial story demonstrates, Brinley was scrupulous about keeping the science realistic; there are no iron moles, anti-gravity boots, or time machines. Everything the boys do could actually be done with technology that was readily available at the time. Our heroes are creative and clever, but always within the bounds of believability, which is one thing that makes the stories so engaging; you can easily imagine them actually happening.

Bertrand Brinley

The thing that makes the mad scientist tales work best, though, is Brinley’s skill as a storyteller. These relaxed, good-humored stories are consummately crafted, and the fun plays out with perfect ease, each always amusing (and often hilarious) incident flowing smoothly from the next. The lively plots neatly combine the surprising and the plausible, the dialogue is natural and occasionally witty, the interaction between the boys is unaffected and believable, and you finish each swiftly moving story feeling refreshed and invigorated, as if you had just taken a brisk swim in a clear, cool lake. The care that Brinley took is evident on every page, and the mad scientist stories can still be read with pleasure long after you’ve graduated from the children’s section. (I know that I’m far from being the only person to feel this way about these books — before Purple House Press brought them back into print in 2001, battered Scholastic paperback copies from the seventies would often sell online for over a hundred dollars.)

The mad scientist stories are very much products of the optimistic era of the early sixties, and their strengths and weaknesses derive from that time. Diversity is nowhere to be seen; the characters are all white (which was likely a fairly accurate depiction of many small Midwestern towns in 1960) and our club members are all boys (though Brinley did induct two female characters into the organization in the posthumous final novel). Though they’re in their early to mid-teens, none of the mad scientists seem to have any interest in the opposite sex; none of them even drive. (They get around on bicycles.) Families are seemingly intact (parents barely appear in the books, in fact) and it’s taken for granted that life is benign and filled with nothing but exciting opportunities, making Brinley’s work very different from today’s “get used to the grim facts while you can, kid” breed of YA books.

Brain power and elbow grease

Truly, the stories of the Mad Scientists’ Club exist outside of ordinary space and time; they take place in the idyllic, unfettered world that is a child’s perfect dream (a dream with walkie-talkies and rockets!) Our seven heroes think for themselves and overcome all obstacles, and in the course of their adventures they go where they please and do what they want, free from adult interference. I haven’t done an exhaustive, line-by-line examination of every page, but I’m fairly sure that school never gets mentioned; the stories unfold in an endless summer of fabulous possibilities.

Bertrand Brinley didn’t write down to his audience, but neither did he induce a sweat in himself or in his readers by trying to do any improving or elevating; his purpose was clearly to entertain and delight, and in that he succeeded so well that his stories of the Mad Scientists’ Club are still giving pleasure to readers old and new more than a half a century after they were written. He didn’t have any heavy-handed moral or social lessons to teach, other than imbuing in his young audience the conviction that if they’re willing to combine creative thinking and elbow grease, they can do anything they put their minds to, and in these books, the wide-open world is a wonderful place to explore, especially if you do it in the company of friends. If message there must be, that’s a pretty good one, however young — or old — you are.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Harlan Ellison 1934-2018: Essential and Impossible.

Nice juxtaposition with the immediately preceding BLACK GATE post!

The Mad Scientists’ Club was probably the greatest series of my childhood. It was certainly responsible (along with Lee & Kirby’s Fantastic Four) for my early fascinating with science, and my firm decision (at the age of 12) to get a Ph.D. in engineering… which I did.

A great review revolves around a perfect description, and I think you achieved that perfect description with your title, and this line:

“Truly, the stories of the Mad Scientists’ Club exist outside of ordinary space and time; they take place in the idyllic, unfettered world that is a child’s perfect dream.”

The Mad Scientists’ Club looms large in my childhood memories not just because of the brief hours of pleasure these books gave me, but because of the endless hours I spent daydreaming after reading them. Daydreams of building hovercraft in my back yard powered by old tires, and making fake treasure maps, and much, much more.

Two years after reading them I discovered real science fiction, in the form of Simak, and Asimov, and Piers Anthony. But these books prepared me for a lifelong love of adventure SF. I still love them today.

Thanks for the great memories, Thomas.

Rich,

You mean The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter? I didn’t notice it until you pointed it out!

Oh my lord, I REMEMBER THAT BOOK! Well, the Strawberry Lake Monster, at least …

Me too, guys.

I was also ten in 1970, and I found the first volume in my school library. This was the only time in my life I was asked to leave a library, as I was unable to restrain my hoots of laughter.

The story with the flying mannequin, equipped with a speaker through which the boys could make him talk, perched alongside a commemorative statue atop a tall pillar in the city square, mocking the town constable by declaring that if the lawman should ascend the pillar he would “pull his moustache with both hands” sent me literally fleeing for the exit.

Many years later, I remembered the book, ordered a battered old Scholastic paperback, and read the stories aloud to my young son. It got him laughing pretty good, but the world in which the Mad Scientist Club exists,as idealized as it may be, is much closer to the world I grew up in than the world in which he found himself.

You were born in 1960, John? Always nice to meet another member of the dwindling cohort, someone who I know will get any obscure reference I might make to Jimmy Carter or Charlie’s Angels or Howard Cosell.

How’s your sacroiliac?

Oh my goodness. Yes, I loved these. I really ought to get around to reading the last two. I proudly retain the original two volumes from back in the day.

And I have to agree, much as I loved so many of them, it was The Mysterious Flying Man that would get me hooting in laughter every time I read it.

Likewise, that depiction of life has a lot more in common with the ’70s when I grew up than it does these days for my kids, who nonetheless loved the stories themselves when they were old enough to read them.

Are these books available anywhere? Or at least without spending a fortune?

A search on Abebooks.com shows that there are a bunch of fairly inexpensive copies available from various booksellers.

The Purple House Press editions are still in print. Very nice illustrated hardcovers, available from Amazon for less than 20$ each.