Standing on Zanzibar

Toronto police constable Ken Lam confronts the perpetrator of the Yonge Street van massacre,

April 23, 2018. The driver left his vehicle and repeatedly “drew” his cellphone as if it were a

firearm, pointing it and shouting at Lam to shoot him. Without firing a shot, the constable

forced the suspect to the sidewalk and handcuffed him.

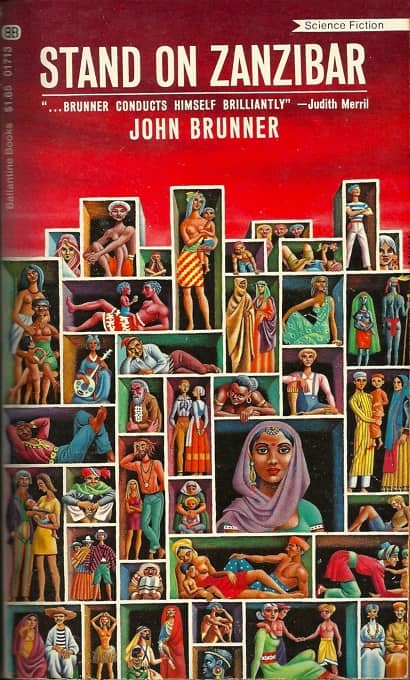

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar. Besides its wonderful title (say it aloud!), the 1968 novel is worth remembering for its author’s uncanny predictions of what 21st century culture and technology might look like.

I use the word “predictions” hesitantly, since I feel that too often we lend a sort of second-rate legitimacy to authors who write stories of the future when we focus on such of their predictions that may have, in some way or other, “come true.” Jules Verne “predicted” the submarine, H.G. Wells tank and aerial warfare, E.M. Forster the internet, and so on. It becomes a form of damning with faint praise. If we focus on an author’s talent for alleged “prediction,” we can overlook the extent to which in expostulating futures, these authors actually wrote about their own time, and did so with insight and creativity. From this point of view, the extrapolations that didn’t “come true” are just as meaningful as those that did, but by focusing on just the “accurate” predictions, by depicting these writers as somehow Nostradamus-type prophets, we make clear that they’re not being judged for their literary value. Instead, they have been relegated to a room separate from that of the genuine canon of literary greats, their predictive ability categorizing each of them less as a genuine creative artist than as a clever algorithm, like a particularly well-programmed weather app.

Indeed, the SF genre is full of talented artists who remained within the genre and never particularly got their due as literary writers: the iconic status that such prolific genre authors as Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, and Harlan Ellison now enjoy was gained not when they wrote specifically “literary” books, but when they skipped that step and when straight into writing scripts for well-regarded films and TV shows, a kind of canonization into popular culture (reinforced by the knowledge that in these cases, their art gained them large paycheques) that any literary writer would envy.

[Click on the image for Zanzibar-sized versions.]

|

|

I begin writing this piece in Hamilton, Ontario on May 18, 2018. Five months into 2018, there have been 16 shootings at US schools that have resulted in injury or death. Although Canada is known as a safer society than our southern neighbour, on April 23 a young man drove a rented van up onto a busy Toronto sidewalk, killing ten people and injuring 14 more. Such incidents are part of a trend towards public violence – taking a weapon to a public place and attacking anyone in range – that is by no means confined to North America. Around the world, attacks in public places by motor vehicles, guns, and knives are hazards that increasingly we take for granted. Like winter blizzards or summer lightning, they could descend on anyone anywhere at any time.

Stand on Zanzibar is set in the year 2010, and Brunner shows an uncanny prescience in presenting a future world that resembles ours in many aspects: from the rise of China as a world presence and the decline of the USA as an industrial power, to a broader acceptance of different sexualities and among men, the widespread use of Viagra-type drugs (overheard at a party: “Charlie, got any stiffener on you?”). One of the most disturbingly accurate visions, however, in this brilliant piece of work, is its introduction of what, in Brunner’s future, are called muckers.

The term is taken from the word amok, a Malay word that first became known in English in the 17th century, when anything like the amok phenomenon was virtually unknown in the west: what Merriam-Webster calls “an episode of sudden mass assault against people or objects usually by a single individual following a period of brooding that has traditionally been regarded as occurring especially in Malaysian culture but is now increasingly viewed as psychopathological behavior occurring worldwide in numerous countries and cultures.” English usage of amok long ago gave rise to the term “running amuck.” In Stand on Zanzibar, muckers are clearly depicted as a response to overpopulation, a response which the mucker themselves can’t control: in the midst of an attack, a mucker according to Brunner is “in a berserk frame of reference and will not feel any pain.”

In the 2010 of Stand on Zanzibar, muckers are reported as routinely as the weather:

The incidence of muckers continues to maintain its high: one in Outer Brooklyn yesterday accounted for 21 victims before the fuzzie-wuzzies fused him, and another is still at large in Evanston, Ill., with a total of eleven and three injured. Across the sea in London a woman mucker took out four as well as her own three-month baby before a mind-present standerby clobbered her. Reports also from Rangoon, Lima and Auckland notch up the day’s total to 69.

Brunner makes sure we know that he is building his future world firmly on a present-day foundation: one chapter of Zanzibar consists of three excerpts from the front page of the November 13, 1966 London Observer: a speculative article on the future cloning of human beings, a report on the longest space walk so far (two hours 28 minutes, a record set by Buzz Aldrin, who three years later walked on the moon with Neil Armstrong), and a report on a shooting in an Arizona beauty school in which an 18-year-old man killed five people, including a child and infant; ”the third mass murder in the United States in four months” after the killing of eight student nurses by Richard Speck in Chicago, and the rampage of the infamous clock tower sniper in Austin, Texas.

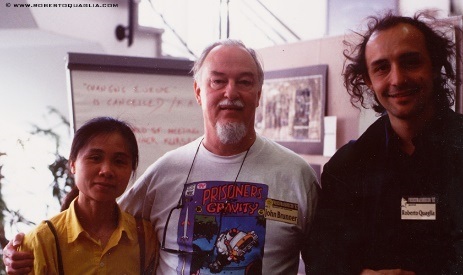

Li Yi Tan Brunner, John Brunner, Roberto Quaglia;

SF Eurocon 1992, Freudenstadt, Germany.

Photo courtesy of Roberto Quaglia.

Post-traumatic stress disorder, religious mania, chronic psychosis: all these are worth arguing as root causes for our present-day “muckers,” but Brunner’s overriding concern is overpopulation. The title of this “non-novel,” as Brunner called it, refers to a quirky example of population mathematics: if every human occupied a space of one foot by two feet when standing, in the early twentieth century it was calculated that the entire earth’s population could have fit onto the Isle of Wight’s 381 square kilometres (147 sq mi). By the time that Brunner’s book was published in 1968, the world’s population of 3.5 billion would need the Isle of Man (572 sq km / 221 sq mi). ) to fit them all. In Brunner’s 2010, world population is seven billion, and as a broadcaster says, “if you allow for every codder and shaggy and appleofmyeye a space one foot by two you could stand us all on the six hundred forty square mile surface of the island of Zanzibar.”

Brunner’s muckers are proliferating because the pressure is just getting too great, in a world with a steadily smaller supply of space and silence, of peace and privacy, of wilderness and wild things. Strangely enough, as the earth’s population increases and stress points appear, with mass poverty, starvation and war exacerbated by human-produced climate change, we don’t hear discussion of overpopulation these days. In the 1960s, when the problem still seemed more remote, it was perhaps a safer topic, but now overpopulation is the elephant in the room. When Brunner began the book in 1966, American author Harry Harrison published Make Room! Make Room!, a police thriller set in New York City in 1999, when New York City has a population of 35 million and the asphalt of the interstate expressways is being chopped up for fuel. As in Zanzibar, the population of Harrison’s world is 7 billion. As I write, the world population is 7.5 billion: don’t look now, but we are already standing on Zanzibar.

David Neil Lee’s last post for us was The Quatermass Experiment: The Shakespeare of Sci-Fi Television. His Lovecraftian YA novel The Midnight Games won the City of Hamilton, Ontario arts council’s 2015 Kerry Schooley Award for the book that “best conveys the spirit of Hamilton.” He has recently completed the first draft of a sequel, The Medusa Deep, projected to be published in 2019. davidneillee.com

Similiar concerns are shared in The Shockwave Rider. Both influenced by the Tofflers’ Future Shock. I agree all seems to be realising in our current social climate