Two, Count ‘Em, Two Nazi Robot T-Rexes

We’re back in the wild, ineffable chaos of the comic book in its infancy. Superman had debuted in 1938, an instant smash. The audience clearly wanted more Supermen, but what did that mean? The 1938 Superman barely resembles today’s omnipotent cosmic hero. He couldn’t fly, couldn’t see through objects, couldn’t move at super-speed, couldn’t freeze objects with his breath, couldn’t emit beams from his eyes, couldn’t survive in space. These gaping holes in his resume gave competitors openings to try to beat Superman at his own game.

Maurice Coyne, Louis Silberkleit, and John L. Goldwater, all veterans of the pulp magazine world though none was yet 40, yoked their first initials together to form MLJ Comics in 1939, launching four titles in four months: Blue Ribbon Comics, Top Notch Comics, Pep Comics, and Zip Comics, which would introduce Steel Sterling, the literal man of steel – a cyborg, though, not a robot. MLJ floundered at first. Blue Ribbon #1 started with Rang-A-Tang, the wonder dog, Dan Hastings, fighting the Mexidians on Mars, and Buck Stacey, young range detective.

Kids yawned, though Rang-A-Tang (apparently a monkey’s uncle) managed to last a whole year, so MLJ tried a blatant Superman imitation in Pep Comics #1, January 1940, by introducing The Comet.

John Dickerson, a young scientist, discovers a gas that is fifty times lighter than hydrogen. He also discovers that, by injecting small doses of the gas into his bloodstream, his body becomes light enough to make great leaps through the air!

After many such injections, he finds that the gas accumulates in the eyes and throws off two powerful beams — These rays, when they cross each other, cause whatever he looks at to disintegrate completely!!!

Now that’s entertainment. The Comet was written and drawn by Jack Cole, creator of Plastic Man and several zillion other strips. Except that he drew them for other companies’ comics. By Pep Comics #16, June 1941, The Comet was being penciled by the awful Lin Streeter and demoted to the third spot in the book, behind “Danny in Wonderland.”

Something drastic needed to be done. Usually strips simply vanished without explanation. MLJ tried an experiment. In Pep Comics #17, July 1941, the Comet is killed by gangsters while shielding his brother, one of the first comic heroes to die on page. Bob swears vengeance to his brother’s girl friend, Thelma.

I’ll carry on for him Thel! I’ll bring his murderers to the hangman! I’ll be their hangman!

And so The Hangman was born. Despite a complete lack of super-powers — odd for someone who had access to his brother’s laboratory — The Hangman strip outlasted The Comet by a wide margin, staying in Pep Comics until issue #47. He must have been an instant hit, himself, because he graduated to his own comic in Winter 1942, starring in 4 of 6 stories in Special Comics #1. There has to be a hidden story behind that, because the title became Hangman Comics with #2 and Special Comics was never seen again.

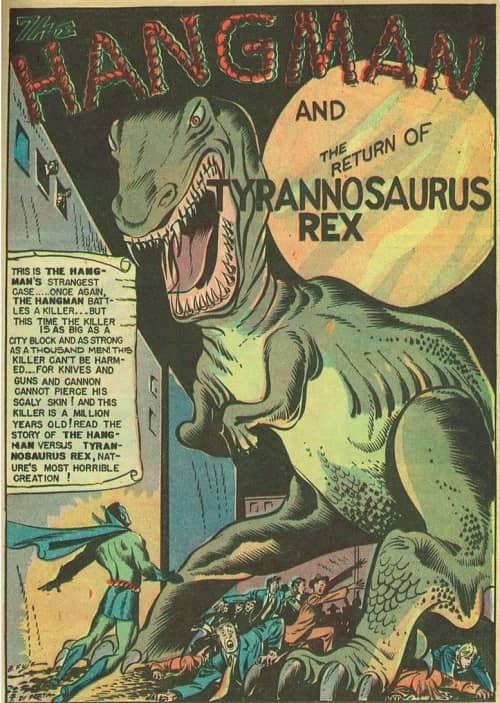

What readers thrilled to, as shown on top, was Hangman Comics #4, Fall 1942, featuring “The Return of Tyrannosaurus Rex,” drawn by Bob Fujitani with no credited writer. In most comics that title would imply that a villain had previously appeared in another issue, but here the “return” meant a return to the living, with a scientist finding a live T-Rex in “a hidden mountain pass in Africa.”

That would make me suspicious, more so when the scientist says that dinosaurs lived in “1,000,000 B.C.” Finishing the job would be his name, Dr. Gonig, a letter off from the Yiddish gonif, meaning a thief or scoundrel. (Jewish writers were always sticking Yiddish puns into names, feeling understandably safe that they’d never be caught by anyone who would report them.)

The Hangman jumps into action, commandeering a huge dockside crane. Which doesn’t faze the monster at all.

If that weren’t weird enough, the dinosaur breaks out of its crate and somehow starts rampaging in Baltimore, Detroit, and San Francisco. Nobody, including the Hangman, is bright enough to wonder how it’s getting across country. After endless carnage and hundreds of deaths, the penny drops. The T-Rex is attacking defense plants! And they used to say dinosaurs were the ones with brains the size of a walnut. That hint is all the Hangman need to stake out the most likely next target: Camden, NJ. (You knew that, right?)

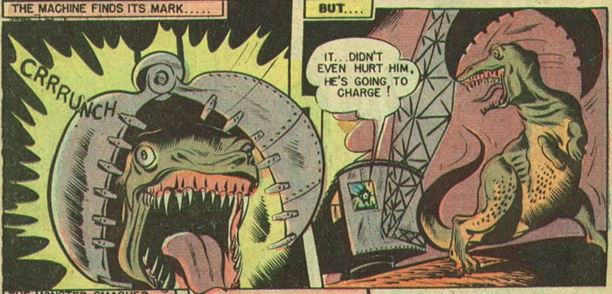

A squadron of tanks shoot the T-Rex. Which still doesn’t stop it. Not until the Hangman literally steps in it does he put two and two together.

Now that he knows the monster is a phony, he makes the only sensible move: he runs into its mouth.

The Hangman is easily overpowered by the scientist and his gang of Nazis controlling the T-Rex from inside the head. And beats them all up. Nah, too easy. They overpower him and are about to put a bullet into his brain.

How does he get out of this mess? Here’s your chance to think like a comic book writer. The fight is taking place on a beach lining the Delaware River, across from Philadelphia, near where actual ironworks were and still are at river level so they can place their output directly onto barges.

Got it? Right. The T-Rex falls over a thousand-foot-high sheer cliff. Maybe Fujitani was taking a walk around Manhattan and got mesmerized by the Jersey Palisades and figured, every city has sheer cliffs on its rivers, amirite? As a non-comic writer, you might also succumb to the fallacy that falling off a cliff is not conducive to anyone’s survival. Wrong. Only bad guys are killed by falls. The Hangman thinks fast and literally runs to the safest spot inside the robot: its claw. You and I might think that would be the thinnest, weakest spot on a robot T-Rex, but he’s right and we’re wrong, because he emerges without a tear to his costume or a smudge on his square jaw.

MLJ pulled the noose on the Hangman after issue #8. By that time a certain all-American boy named Archie had been introduced in Pep Comics #22. Like the Hangman, MLJ knew a clue when they stumbled over one. The company’s name changed to Archie Comics Publications and made about a billion dollars by avoiding superheroes.

The contest for ever stranger heroes and ever-more menacing villains went on, nevertheless. A second Nazi Tyrannosaur appeared just a year after the first. Another blatant imitation or independent logic? Here’s the story for you to judge.

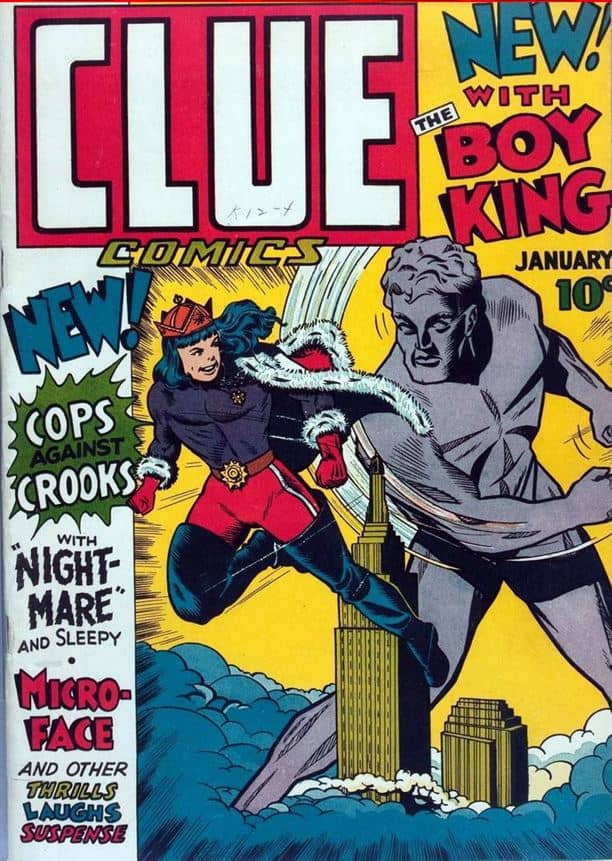

Wikipedia claims to house 5,000,000 pages and I sometimes think that 3,000,000 of them are about comics. Yet not one of them contains a reference to “The Boy King and the Giant,” even on the page for Hillman Periodicals, its publisher. The strip appeared in the January 1943 first issue of Clue Comics, for which no entry exists either, and isn’t mentioned in the bios for writer Charles Biro or inker Dan Barry. Penciler Alan Mendel doesn’t even rate a bio. Eau de obscure. I love it.

The premise of the Boy King is wild even by comic standards. The Nazis invade the peaceful kingdom of Swisslakia (which sits on a map exactly where Switzerland would be in our universe: they didn’t even try to pretend) and gun down the royal family. They are taken out to a field to be buried in secret, but the Nazis are somehow as inept in shooting people as they are in everything else in the world of comics. The King is merely almost dead, living just long enough to tell his son about the legend that Nostradamus “created a mechanical giant who would have but one master .. the person who screws the bolt in the giant’s head!” The son, now the Boy King, starts digging at the foot of Mt. Royal and in no time uncovers the giant. The giant stands up .. and up .. and up, the largest robot in all fiction.

How large is he? Biro changes his size, not just with every issue, but with every panel. At his largest he is very. very large indeed. The Boy King escapes to America because the giant walks across the Atlantic, and easily picks up Nazi ships sent to sink him.

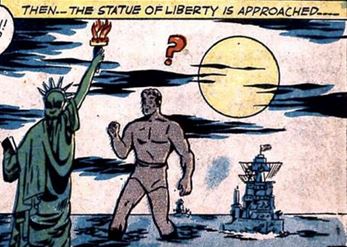

Later in that same issue, though, he’s head to head with the Statue of Liberty. It’s love at first sight.

|

|

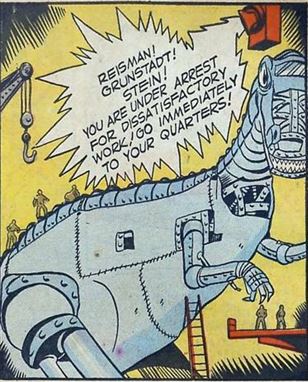

The Boy King and his giant take up residence in New York. The Clue crew almost immediately realized they’d made a big mistake. First, a giant that dwarfs skyscrapers can’t move around Manhattan without destroying more buildings than the villains. And a strip whose entire raison d’être is fighting Nazis loses most of its meaning fighting crooks. Some unknown writer figured a solution in issue #4, June 1943. Hitler, always looking for an edge, orders a giant robot T-Rex built to fight the Swisslakian giant.

|

|

You’ve got to admire the way Dan Barry sticks a swastika legband on the T-Rex, just in case any dim reader might want to identify with the dinosaur.

Just as the giant had, the T-Rex now wades the Atlantic, gobbling up American planes and ships in the same way. The Boy King rides into action, the two monsters meeting in the middle of the ocean, not even getting their knees wet.

So epic is the battle that it bleeds over into issue #5, July 1943.

Ever wonder how the good guys always win? Raymond Chandler once said “this is what is vulgarly known as having God sit in your lap.” The Boy King stands unsecured on the giant’s shoulders while it boxes and wrestles the T-Rex. Yet he doesn’t move an inch throughout the mayhem while the bad guy, who is protected inside the metal skull, falls through a window. Go figure.

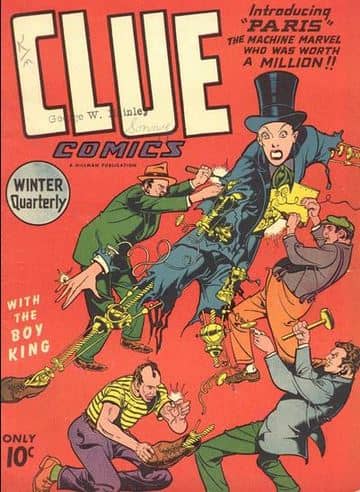

Clue Comics died with issue #9, Winter 1944, before being brought back in 1946 as a crime comic. The Boy King got more and more Americanized but still fought some weird menaces, including an all-gold king and a robot whose inner parts were coated with diamonds. That robot was even queerer than one can suppose, to paraphrase Haldane.

The face is that of a woman and is wearing lipstick, an impossibility for a comic book male in 1944. Yet Paris is always referred to as a “he.” I can’t explain it. The past is a different country.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. His website is flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Servotron Abolishes the Three Laws of Robotics.

Haha, I’ve been reading a lot of Golden Age comics lately, although I haven’t gotten as far as these particular ones yet. Mostly just enjoying a lot of the Eisner studio work – The Flame is my favorite superhero series so far, mostly thanks to Lou Fine’s art, although Bill Everett’s Amazing Man is pretty fun, too.